History of Minoan Crete Perhaps the Most Sophisticated Bronze Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Writing Systems (Continued)

Clst 181SK Ancient Greece and the Origins of Western Culture The Ancient Mediterranean A Basic Chronology Clst 181SK Ancient Greece and the Origins of Western Culture 1. Early Mesopotamian Civilizations Sumer and the Sumerians - writing appears about 3500 BCE Akkadian empire (c. 2350 BCE) First Assyrian empire (c. 2150 BCE) First Babylonian empire (c. 1830 BCE) Clst 181SK Ancient Greece and the Origins of Western Culture 1. Early Greek Civilizations The Minoan Civilization (1900-1450 BCE) Crete ! The Mycenaean Civilization (1450-1200 BCE) Mainland Greece, especially the Peloponnesus Clst 181SK Ancient Greece and the Origins of Western Culture The Ancient Mediterranean Maps M Danuvius a R s r O o g I in u R e MOESIAs FE r A IN D SUPERIOR MOESI US AEM H NS MO Hebrus I A BOSPHORUS R A C A x H io T I s RHODOPE L MONS PROPONTIS L ONI IA Y CED A YN MA Thasos ITH R B I C CHALCATHOS U MONS MYSIA M OLYMPUS Lemnos A P MONS HELLESPONTUS S R I I O N A M I N Lesbos A E D E P U O mos I er Corcyra R S L H AEGAEUM I U s M THESSALIA S S u O Scyrus o l N Euboea L e Y IONIUM MARE D h r S Chios IO IA e A c NI d MARE Leucas CA ET BOE A n R A A OL a N IA OT ae Ithaca AN IA M IA Samos A Andros CA A CHAEA TT Ikaria RI IC A Cephallenia A A R Aegina Delos Zacynthus C A D I A L Paros Y C IA PELOPONNESUSL Naxos Cos AC E MYRTOUM D A MARE E Melos Thera Rhodos M O N Cythera CRETICUM Karpathos MARE CRETA INTERNUM MARE This material originated on the Interactive Ancient Mediterranean Web site (http://iam.classics.unc.edu) It has been copied, reused or redistributed under the terms of IAM's fair use policy. -

Mycenaean Seminar List

THE MYCENAEAN SEMINAR 1954–2017 Olga Krzyszkowska and Andrew Shapland This list gives titles of individual seminars (and related events) with links and references to their publication in BICS. Initially discussions and some summaries were printed in the Seminar minutes, which were privately circulated (only from 21st January 1959 were minutes headed ‘Mycenaean Seminar’). The first published summaries appeared in BICS 13 (1966), soon superseding the minutes. Some seminars/public lectures were published as full-length articles (page references to these are given in bold). Summaries were usually, but not always, published in the subsequent year’s BICS and some never appeared at all. However, from 1993–94 onwards summaries of all Seminars and virtually all public lectures relating to Aegean prehistory held at the Institute were published in BICS. The summaries for 2014–15 were the last to appear in the print edition of BICS, which has now become thematic. The summaries for 2015–16 and 2016–17 are published in an online supplement to BICS available at the Humanities Digital Library. 1953–1954 The first meeting was on 27 January 1954, and there were four subsequent meetings that academic year. Minutes were kept from the second meeting onwards. 1954–55 Papers were given by J. Chadwick, P. B. S. Andrews, R. D. Barnett, O. Gurney, F. Stubbings, L. R. Palmer, T. B. L. Webster and M. Ventris. 1955–56 M. Ventris ‘Pylos Ta series’ S. Piggott ‘Mycenaeans and the West’ R. A. Higgins ‘Archaeological basis for the Ta tablets’ (BICS 3: 39–44) G. L. Huxley ‘Mycenaean history and the Homeric Catalogue of Ships’ (BICS 3: 19–30) M. -

Linguistic Study About the Origins of the Aegean Scripts

Anistoriton Journal, vol. 15 (2016-2017) Essays 1 Cretan Hieroglyphics The Ornamental and Ritual Version of the Cretan Protolinear Script The Cretan Hieroglyphic script is conventionally classified as one of the five Aegean scripts, along with Linear-A, Linear-B and the two Cypriot Syllabaries, namely the Cypro-Minoan and the Cypriot Greek Syllabary, the latter ones being regarded as such because of their pictographic and phonetic similarities to the former ones. Cretan Hieroglyphics are encountered in the Aegean Sea area during the 2nd millennium BC. Their relationship to Linear-A is still in dispute, while the conveyed language (or languages) is still considered unknown. The authors argue herein that the Cretan Hieroglyphic script is simply a decorative version of Linear-A (or, more precisely, of the lost Cretan Protolinear script that is the ancestor of all the Aegean scripts) which was used mainly by the seal-makers or for ritual usage. The conveyed language must be a conservative form of Sumerian, as Cretan Hieroglyphic is strictly associated with the original and mainstream Minoan culture and religion – in contrast to Linear-A which was used for several other languages – while the phonetic values of signs have the same Sumerian origin as in Cretan Protolinear. Introduction The three syllabaries that were used in the Aegean area during the 2nd millennium BC were the Cretan Hieroglyphics, Linear-A and Linear-B. The latter conveys Mycenaean Greek, which is the oldest known written form of Greek, encountered after the 15th century BC. Linear-A is still regarded as a direct descendant of the Cretan Hieroglyphics, conveying the unknown language or languages of the Minoans (Davis 2010). -

Journal of Eurasian Studies

JOURNAL OF EURASIAN STUDIES _____________________________________________________________________________________ Journal of the Gábor Bálint de Szentkatolna Society Founded: 2009. Internet: www.federatio.org/joes.html _____________________________________________________________________________________ Volume I., Issue 4. / October — December 2009 ____________________ ISSN 1877-4199 October-December 2009 JOURNAL OF EURASIAN STUDIES Volume I., Issue 4. _____________________________________________________________________________________ Publisher Foundation 'Stichting MIKES INTERNATIONAL', established in The Hague, Holland. Account: Postbank rek.nr. 7528240 Registered: Stichtingenregister: S 41158447 Kamer van Koophandel en Fabrieken Den Haag Distribution The periodical can be downloaded from the following Internet-address: http://www.federatio.org/joes.html If you wish to subscribe to the email mailing list, you can do it by sending an email to the following address: [email protected] The publisher has no financial sources. It is supported by many in the form of voluntary work and gifts. We kindly appreciate your gifts. Address The Editors and the Publisher can be contacted at the following addresses: Email: [email protected] Postal address: P.O. Box 10249, 2501 HE, Den Haag, Holland Individual authors are responsible for facts included and views expressed in their articles. _____________________________________ ISSN 1877-4199 © Mikes International, 2001-2009, All Rights Reserved _____________________________________________________________________________________ -

Modern Minoica As Religious Focus in Contemporary Paganism

The artifice of Daidalos: Modern Minoica as religious focus in contemporary Paganism More than a century after its discovery by Sir Arthur Evans, Minoan Crete continues to be envisioned in the popular mind according to the outdated scholarship of the early twentieth century: as a peace-loving, matriarchal, Goddess-worshipping utopia. This is primarily a consequence of more up-to-date archaeological scholarship, which challenges this model of Minoan religion, not being easily accessible to a non-scholarly audience. This paper examines the use of Minoan religion by two modern Pagan groups: the Goddess Movement and the Minoan Brotherhood, both established in the late twentieth century and still active. As a consequence of their reliance upon early twentieth-century scholarship, each group interprets Minoan religion in an idealistic and romantic manner which, while suiting their religious purposes, is historically inaccurate. Beginning with some background to the Goddess Movement, its idiosyncratic version of history, and the position of Minoan Crete within that timeline, the present study will examine the interpretation of Minoan religion by two early twentieth century scholars, Jane Ellen Harrison and the aforementioned Sir Arthur Evans—both of whom directly influenced popular ideas on the Minoans. Next, a brief look at the use of Minoan religious iconography within Dianic Feminist Witchcraft, founded by Zsuzsanna Budapest, will be followed by closer focus on one of the main advocates of modern Goddess worship, thealogian Carol P. Christ, and on the founder of the Minoan Brotherhood, Eddie Buczynski. The use of Minoan religion by the Goddess Movement and the Minoan Brotherhood will be critiqued in the light of Minoan archaeology, leading to the conclusion that although it provides an empowering model upon which to base their own beliefs and practices, the versions of Minoan religion espoused by the Goddess Movement and the Minoan Brotherhood are historically inaccurate and more modern than ancient. -

Ancient Greece

αρχαία Ελλάδα (Ancient Greece) The Birthplace of Western Civilization Marshall High School Mr. Cline Western Civilization I: Ancient Foundations Unit Three AA * European Civilization • Neolithic Europe • Europe’s earliest farming communities developed in Greece and the Balkans around 6500 B.C. • Their staple crops of emmer wheat and barley were of near eastern origin, indicating that farming was introduced by settlers from Anatolia • Farming spread most rapidly through Mediterranean Europe. • Society was mostly composed of small, loose knit, extended family units or clans • They marked their territory through the construction of megalithic tombs and astronomical markers • Stonehenge in England • Hanobukten, Sweden * European Civilization • Neolithic Europe • Society was mostly composed of small, loose knit, extended family units or clans • These were usually built over several seasons on a part time basis, and required little organization • However, larger monuments such as Stonehenge are evidence of larger, more complex societies requiring the civic organization of a territorial chiefdom that could command labor and resources over a wide area. • Yet, even these relatively complex societies had no towns or cities, and were not literate * European Civilization • Ancient Aegean Civilization • Minos and the Minotaur. Helen of Troy. Odysseus and his Odyssey. These names, still famous today, bring to mind the glories of the Bronze Age Aegean. • But what was the truth behind these legends? • The Wine Dark Sea • In Greek Epic, the sea was always described as “wine dark”, a common appellation used by many Indo European peoples and languages. • It is even speculated that the color blue was not known at this time. Not because they could not see it, but because their society just had no word for it! • The Aegean Sea is the body of water which lays to the east of Greece, west of Turkey, and north of the island of Crete. -

Bronze Age Trade in the Mediterranean

STUDIESSTUDIES ININ MEDITERRANEAN MEDITERRANEAN ARCHAEOLOGYARCHAEOLOGY VOL.VOL. XCxc BRONZEBRONZE AGEAGE TRADETRADE ININ THE MEDITERRANEANMEDITERRANEAN PapersPapers PresentedPresented at the ConferenceConference heldheld atat Rewley Rewley House, House, Oxford, Oxford, in in DecemberDecember 1989 EditedEdited byby N.H.N.H. GaleGale JONSEREDJONSERED 19911991 PAULPAUL ASTROMSASTROMS FORLAGFORLAG CONTENTS Preface iv H.W. Catling:Catling: BronzeBronze AgeAge Trade in thethe Mediterranean: a View 11 A.M. Snodgrass:Snodgrass: BronzeBronze Age Exchange: a Minimalist PositionPosition 1515 A.B. Knapp:Knapp: Spice,Spice, Drugs,Drugs, GrainGrain andand Grog:Grog: OrganicOrganic GoodsGoods inin BronzeBronze Age East 21 Mediterranean TradeTrade G.F. Bass:Bass: EvidenceEvidence of Trade from Bronze Age ShipwrecksShipwrecks 69 S.S. McGrail: BronzeBronze AgeAge SeafaringSeafaring inin thethe Mediterranean:Mediterranean: a ViewView fromfrom N.W. EuropeEurope 8383 J.F. CherryCherry && A.B.A.B. Knapp: Knapp: Quantitative Quantitative Provenance Provenance StudiesStudies and Bronze Age 9292 Trade inin thethe Mediterranean: Mediterranean: SomeSome PreliminaryPreliminary ReflectionsReflections E.B. French:French: TracingTracing ExportsExports of MycenaeanMycenaean Pottery: the Manchester ContributionContribution 121121 R.E.R.E. JonesJones && L.L. Vagnetti: Vagnetti: TradersTraders and and CraftsmenCraftsmen inin thethe CentralCentral Mediterranean:Mediterranean: 127127 ArchaeologicalArchaeological EvidenceEvidence andand ArchaeometricArchaeometric Research -

150506-Woudhuizen Bw.Ps, Page 1-168 @ Normalize ( Microsoft

The Ethnicity of the Sea Peoples 1 2 THE ETHNICITY OF THE SEA PEOPLES DE ETNICITEIT VAN DE ZEEVOLKEN Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof.dr. S.W.J. Lamberts en volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op vrijdag 28 april 2006 om 13.30 uur door Frederik Christiaan Woudhuizen geboren te Zutphen 3 Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof.dr. W.M.J. van Binsbergen Overige leden: Prof.dr. R.F. Docter Prof.dr. J. de Mul Prof.dr. J. de Roos 4 To my parents “Dieser Befund legt somit die Auffassung nahe, daß zumindest für den Kern der ‘Seevölker’-Bewegung des 14.-12. Jh. v. Chr. mit Krieger-Stammesgruppen von ausgeprägter ethnischer Identität – und nicht lediglich mit einem diffus fluktuierenden Piratentum – zu rechnen ist.” (Lehmann 1985: 58) 5 CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................................................................................................9 Note on the Transcription, especially of Proper Names....................................................................................................11 List of Figures...................................................................................................................................................................12 List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................................................13 -

Diachronic Homer and a Cretan Odyssey

Oral Tradition, 31/1 (2017):3-50 Diachronic Homer and a Cretan Odyssey Gregory Nagy Introduction I explore here the kaleidoscopic world of Homer and Homeric poetry from a diachronic perspective, combining it with a synchronic perspective. The terms synchronic and diachronic, as I use them here, come from linguistics.1 When linguists use the word synchronic, they are thinking of a given structure as it exists in a given time and space; when they use diachronic, they are thinking of that structure as it evolves through time.2 From a diachronic perspective, the structure that we know as Homeric poetry can be viewed, I argue, as an evolving medium. But there is more to it. When you look at Homeric poetry from a diachronic perspective, you will see not only an evolving medium of oral poetry. You will see also a medium that actually views itself diachronically. In other words, Homeric poetry demonstrates aspects of its own evolution. A case in point is “the Cretan Odyssey”—or, better, “a Cretan Odyssey”—as reflected in the “lying tales” of Odysseus in the Odyssey. These tales, as we will see, give the medium an opportunity to open windows into an Odyssey that is otherwise unknown. In the alternative universe of this “Cretan Odyssey,” the adventures of Odysseus take place in the exotic context of Minoan-Mycenaean civilization. Part 1: Minoan-Mycenaean Civilization and Memories of a Sea-Empire3 Introduction From the start, I say “Minoan-Mycenaean civilization,” not “Minoan” and “Mycenaean” separately. This is because elements of Minoan civilization become eventually infused with elements we find in Mycenaean civilization. -

The Evolution of Civilizations Singled out for National Awards by a National Committee Headed by George Gallup

The Evolution of Civilizations n this perceptive look at the factors behind the rise and fall of I civilizations, Professor Quigley seeks to establish the analytical tools necessary for understanding history. He examines the applica- tion of scientific method to the social sciences, then establishes his historical hypotheses. He poses a division of culture into six levels, from the more abstract to the more concrete—intellectual, religious, social, political, economic, and military—and he identifies seven stages of historical change for all civilizations: mixture, gestation, expansion, conflict, universal empire, decay, and invasion. Quigley tests these hypotheses by a detailed analysis of five major civilizations: the Mesopotamian, the Canaanite, the Minoan, the classical, and the Western. "He has reached sounder ground than has Arnold J. Toynbee" —Christian Science Monitor. "Studies of this nature, rare in American historiography, should be welcomed. Quigley's juxtaposition of facts in a novel order is often provocative, and his work yields a harvest of insights"—American Historical Review. "Extremely illuminating" —Kirkus Reviews. "This is an amazing book. Quigley avoids the lingo of expertise; indeed, the whole performance is sane, impres- sively analytical, and well balanced"—Library Journal. CARROLL QUIGLEY taught the history of civilization at the Georgetown School of Foreign Service, and was the author of Trag- edy and Hope: The World in Our Time. Contents Diagrams, Tables, and Maps .................................................... 11 Foreword, by Harry J. Hogan ................................................... 13 Preface to the First Edition ....................................................... 23 1. Scientific Method and the Social Sciences.......................... 31 2. Man and Culture.................................................................. 49 3. Groups, Societies, and Civilizations.................................... 67 4. Historical Analysis .............................................................. 85 5. -

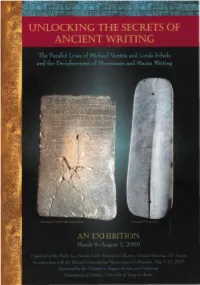

Unlocking the Secrets of Ancient Writing

Figure 1: Left Cover Photograph Linear B tablet, Pylos Tn 316 Mycenaean, Late Helladic III B, 1200 B.C.E. Clay, accidental ly fired H 7.8 in. x W 5.0 in. x D 0.9 in. National Archaeological Museum, Athens Photograph © PASP slide archives OLM) On the front side of Pylos T n 3 16, the famous 'human sacrifice' tablet, the scribe experimented with the layout for entering information about ceremonial offerings made by the community of Pylos (pu-ro in large characters twice at left) to sanctuaries in the palatial territory of Bronze Age Messenia. Note the ideographic characters for golden vases and for human beings. Entries continue on the verso. It is debated whether the MAN and WOMAN entries j,,-, ,/ ; / were 'sacrificial victims' or 'sacristans' bringing the vases. The lower \11 part of the rectosurface has graffiti, possibly the Linear B abc's or y:L iroha, written by the scribe in testing the readiness of the clay. Cf. ~-- - ---.'.._ )/ /11:v T.G. Palaima, "Kn02-Tn 316," in S. Deger-Jalkoczy eta!. eds., FloreantStudia Mycenaea(Vienna 1999) Band II, 437-461. Figure 2: Drawing of the front of tablet PYTn 316. Line drawing by Emmett L. Bennett, Jr. Figure3: Right Cover Photograph Jade celt, the Leiden Plaque Maya, Early Classic period, C.E. 320 . Incised jade = H 8.5 in. x W 3.4 in. x D 0.4 in. Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden, Holland Photograph © Justin Kerr, K2909 This incised jade, once used as a royal belt ornament , carries an inscription on the versothat tells of the accession (the "seating") of a Maya ruler which occurred on September 17, C.E. -

Talking Neolithic: the Case for Hatto-Minoan and Its Relationship to Sumerian

Talking Neolithic: The Case for Hatto-Minoan and its Relationship to Sumerian Peter Schrijver University of Utrecht It is argued that the Minoan language of second-millennium BC Crete stands a good chance of being descended from the language that was imported into Crete by the earliest farmers that colonized the Island in the 7th millennium BC. Evidence is presented that links Minoan to the Hattic language of second- millennium BC northern Anatolia. An analysis of the Hattic verbal system supports the hypothesis that in turn Hattic is related to Sumerian. The existence of a Hatto-Sumero-Minoan language family is posited, which predates the expansions of Semitic and Indo-European in the Near East and which is implicated in the spread of migrant farmers into Europe. A word for ’pig’ is reconstructed for that language family. 1. Language, genes and culture The expansion of a language across a geographical area takes place as a result of two mechanisms: the language is taken along by people who migrate into new territory, or the language is adopted by local populations beside or instead of their original language. Before the times of widespread formal education, mass media and the internet, language spread by acculturation always went hand in hand with spread by migration: only the presence of migrant native speakers in a new territory is capable of exposing the natives to the new language and of creating social pressure to adopt that language. Exposure and social pressure are what it takes for a population to trade its native language for a different one.