Towards a Digital Land of Song: a Digital Approach to the Archival Record of Welsh Traditional Music, Its Performance and Its Reception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Purpose Washington University in St

Purpose Washington University in St. Louis 2017–18 Annual Report $711.8M 25 Research support 2017–18 Nobel laureates associated with the university 4,182 15,396 Total faculty Total enrollment, fall 2017 7,087 undergraduate; 6,962 graduate and professional; 20 1,347 part-time and other Number of top 15 graduate and professional programs U.S. News & World Report, 2017–18 30,463 Class of 2021 applications, first-year students entering fall 2017 18 Rank of undergraduate program 1,778 U.S. News & World Report, 2017–18, National Universities Category Class of 2021 enrollment, first-year students entering fall 2017 138,548 >2,300 Number of alumni addresses on record July 2017 Total acres, including Danforth Campus, Medical Campus, West Campus, North Campus, South Campus, 560 Music Center, Lewis Center, and Tyson Research Center $7.7B Total endowment as of June 30, 2018 22 Number of Danforth Campus buildings on the National 16,428 Register of Historic Places Total employees $248M Amount university provided in undergraduate $3.5B and graduate scholarship support in 2017-18 Total operating revenues as of June 30, 2018 4,638 All degrees awarded 2017–18 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Letter from the Chair and Chancellor 18 Purpose 38 Financial Highlights 4 Leading Together 34 Year in Review 4 | Purpose LETTER FROM THE CHAIR AND THE CHANCELLOR Mark S. Wrighton, Chancellor, and Craig D. Schnuck, Chair, Board of Trustees The campaign has laid On June 30, 2018, we marked the conclusion of Leading Together: The Campaign for the foundation for a Washington University, the most successful fundraising initiative in our history. -

Braids of Song Gwead Y Gân

Braids of Song Gwead y Gân by Mari Morgan BMus (Hons), MA. Supervised by: Professor Menna Elfyn and Dr Jeni Williams Submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Creative Writing University of Wales Trinity Saint David 2019 Er cof am fy nhad, Y Parchedig E D Morgan a ddiogelodd drysor. In memory of my father, the Reverend E D Morgan who preserved a treasure. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With grateful thanks for the generous support of: North America Wales Foundation (Dr Philip Davies and Hefina Phillips) Welsh Women’s Clubs of America (Barbara Crysler) Welsh Society of Philadelphia (Jack R. Williams, Jr.) Diolch o galon: for the experience and guidance of my supervisors, Professor Menna Elfyn and Dr Jeni Williams, for the friendship and encouragement of Karen Rice, for my siblings always, Nest ac Arwel, for the love and steadfast support of Lisa E Hopkins, and for the unconditional love of my mother, Thelma Morgan. Diolch am fod yn gefn. iv Abstract The desire to recognise the richness, humanity, and cross fertilisation of cultures and identities that built today’s America is the starting point for Braids of Song. Its overarching concerns trace the interrelation between immigration, identity and creativity within a Welsh Trans-Atlantic context. Braids of Song is a mixed-genre collection of stories that acknowledges the preciousness of culture; in particular, the music, which is both able to cross different linguistic boundaries and to breach those between melody and language itself. The stories are shared through four intertwined narrative strands in a mixture of literary styles, ranging from creative non-fiction essays and poems to dramatic monologues. -

Eisteddfod / Fall Weekend November 4-6, 2011; Hudson Valley Resort & Spa--See Table of Contents Events at a Glance

**Updated version as of 10/8/11 -- see also calendar listings on p.9 ** Folk Music Society of New York, Inc. October 2011 vol 46, No.9 October Mondays: Irish Traditional Music Session; the Landmark 2 Sun Sea Music Concert: Bob Wright & Bill Doerge, 3-5pm at John Street Church, 44 John Street 5 Wed Folk Open Sing 7 pm in Brooklyn 10 Mon FMSNY Board of Directors Meeting; 7:15, 18 W. 18 St. 14 Fri Daniel Pearl Concert, 8pm at OSA Hall 16 Sun Shanty Sing on Staten Island, 2-5pm 22 Sat North American Urban Folk Music of the 1960s at Elisa- beth Irwin High School, 40 Charlton Street. 1-10pm 26 Wed Newsletter Mailing, 7pm in Jackson Heights (Queens) 28 Fri Dave Trenow House Concert; 8pm upper West Side November Mondays: Irish Traditional Music Session; the Landmark 2 Wed Folk Open Sing 7 pm in Brooklyn 4-6 Fr-Sun Eisteddfod/Fall Weekend; see flyer at end 6 Sun Dave Ruch free concert at Eisteddfod; 11am-noon 11 Fri Michele Choiniere; 8pm at Columbia University 14 Mon FMSNY Board of Directors Meeting; 7:15, 18 W. 18 St. 20 Sun Shanty Sing on Staten Island, 2-5pm Details on pages 2-3; =members $10 Eisteddfod / Fall Weekend November 4-6, 2011; Hudson Valley Resort & Spa--see http://www.eisteddfod-ny.org Table of Contents Events at a Glance .................. 1 Repeating Events Listings ........12 Society Events Details ...........2-4 Calendar Location Info ...........15 Daniel Pearl flyer ................... 4 Folk Music Society Info ..........17 Topical Listing of Society Events 5 Peoples' Voice Cafe Ad ...........18 From The Editor ................... -

APPLICATION for GRANTS UNDER the National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships

U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202-5335 APPLICATION FOR GRANTS UNDER THE National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships CFDA # 84.015A PR/Award # P015A180115 Gramts.gov Tracking#: GRANT12659873 OMB No. , Expiration Date: Closing Date: Jun 25, 2018 PR/Award # P015A180115 **Table of Contents** Form Page 1. Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 e3 2. Standard Budget Sheet (ED 524) e6 3. Assurances Non-Construction Programs (SF 424B) e8 4. Disclosure Of Lobbying Activities (SF-LLL) e10 5. ED GEPA427 Form e11 Attachment - 1 (GEPA_Section_427_IMCLAS1024915422) e12 6. Grants.gov Lobbying Form e17 7. Dept of Education Supplemental Information for SF-424 e18 8. ED Abstract Narrative Form e19 Attachment - 1 (IMCLAS_Abstract20181024915421) e20 9. Project Narrative Form e21 Attachment - 1 (IMCLAS_Narrative_20181024915424) e22 10. Other Narrative Form e82 Attachment - 1 (FY_2018_Profile_Form_IMCLAS1024915425) e83 Attachment - 2 (IMCLAS_Table_Of_Contents_LAS1024915426) e84 Attachment - 3 (IMCLAS_Acronyms_List_20181024915427) e85 Attachment - 4 (IMCLAS_Diverse_Perspectives_and_National_Need_Descriptions1024915428) e87 Attachment - 5 (Appendix_1_IMCLAS_Course_List1024915429) e91 Attachment - 6 (Appendix_2_IMCLAS_Faculty_CVs1024915430) e118 Attachment - 7 e225 (Appendix_3_IMCLAS_Position_Description_for_Positions_to_be_Filled_and_Paid_from_the_Grant1024915431) Attachment - 8 (Appendix_4_IMCLAS_Letters_of_Support1024915436) e226 Attachment - 9 (Appendix_5_IMCLAS_PMF_20181024915437) e232 11. Budget Narrative -

Let's Electrify Scranton with Welsh Pride Festival Registrations

Periodicals Postage PAID at Basking Ridge, NJ The North American Welsh Newspaper® Papur Bro Cymry Gogledd America™ Incorporating Y DRYCH™ © 2011 NINNAU Publications, 11 Post Terrace, Basking Ridge, NJ 07920-2498 Vol. 37, No. 4 July-August 2012 NAFOW Mildred Bangert is Honored Festival Registrations Demand by NINNAU & Y DRYCH Mildred Bangert has dedicated a lifetime to promote Calls for Additional Facilities Welsh culture and to serve her local community. Now that she is retiring from her long held position as Curator of the By Will Fanning Welsh-American Heritage Museum she was instrumental SpringHill Suites by Marriott has been selected as in creating, this newspaper recognizes her public service additional Overflow Hotel for the 2012 North by designating her Recipient of the 2012 NINNAU American Festival of Wales (NAFOW) in Scranton, CITATION. Read below about her accomplishments. Pennsylvania. (Picture on page 3.) This brand new Marriott property, opening mid-June, is located in the nearby Montage Mountain area and just Welsh-American Heritage 10 minutes by car or shuttle bus (5 miles via Interstate 81) from the Hilton Scranton and Conference Center, the Museum Curator Retires Festival Headquarters Hotel. By Jeanne Jones Jindra Modern, comfortable guest suites, with sleeping, work- ing and sitting areas, offer a seamless blend of style and After serving as curator of the function along with luxurious bedding, a microwave, Welsh-American Heritage for mini-fridge, large work desk, free high-speed Internet nearly forty years, Mildred access and spa-like bathroom. Jenkins Bangert has announced Guest suites are $129 per night (plus tax) and are avail- her retirement. -

Teaching and Learning: Pedagogy, Curriculum and Culture

Teaching and Learning Teaching and Learning: Pedagogy, Curriculum and Culture provides an overview of the key issues and dominant theories of teaching and learning as they impact upon the practice of classroom teachers. Punctuated by questions, points for consideration and ideas for further reading and research, the book’s intention is to stimulate discussion and analysis, to support understanding of classroom interactions and to contribute to improved practice. Topics covered include: • an assessment of dominant theories of learning and teaching; • the ways in which public educational policy impinges on local practice; • the nature and role of language and culture in formal educational settings; • an assessment of different models of ‘good teaching’, including the development of whole-school policies; • alternative models of curriculum and pedagogy Alex Moore has taught in a number of inner-London secondary schools, and for ten years lectured on the PCGE and MA programmes at Goldsmiths University of London. He is currently a senior lecturer in Curriculum Studies at the Institute of Education, London University. He has published widely on a range of educational issues, including Teaching Multicultural Students: Culturism and Anti-Culturism in School Classrooms published by RoutledgeFalmer. Key Issues in Teaching and Learning Series Editor: Alex Moore Key Issues in Teaching and Learning is aimed at student teachers, teacher trainers and inservice teachers including teachers on MA courses. Each book focusses on the central issues around a particular topic supported by examples of good practice with suggestions for further reading. These accessible books will help students and teachers to explore and understand critical issues in ways that are challenging, that invite reappraisals of current practices and that provide appropriate links between theory and practice. -

Bron  Chipio Cadair Y Brifwyl Ym Môn

Papur Bro Dyffryn Ogwen Rhifyn 480 . Medi 2017 . 50C (Llun Annes Glynn gan Panorama) gan Glynn Annes (Llun Bron â chipio cadair y brifwyl ym Môn Roedd Annes Glynn yn y grŵp o bump ar frig cystadleuaeth y Gadair ym mhrifwyl Ynys Môn eleni ac mae ardal Dyffryn Ogwen yn ei llongyfarch yn gynnes am ei champ ac yn ymfalchÏo yn ei llwyddiant. Talu teyrnged i’r diweddar Athro Gwyn Thomas a wna yn yr awdl ac mae’n “sôn am hen ddyhead cenedl y Cymry am arwr i’w harwain”. Ei ffugenw yn y gystadleuaeth oedd ‘Am Ryw Hyd’ ac mae wedi seilio’i gwaith ar rai o gerddi mwyaf adnabyddus Gwyn Thomas. Roedd y beirniaid yn cyfeirio at ei gwaith fel “casgliad” yn hytrach nag un cyfanwaith o awdl. Meddai Annes: “Awdl foliant i Gwyn Thomas ydi hi ond mae hi hefyd yn ystyried y modd yr ydan ni fel cenedl wedi edrych i gyfeiriad arwr delfrydol i’n harwain ni allan o’n trybini dros y canrifoedd. Mae’r ffaith fod Gwyn wedi astudio a thaflu goleuni ar yr union elfen hon yn yr Hen Ganu ac mewn canu ddiweddarach, Annes Glynn a ddaeth yn uchel yn y rhestr deilyngdod am gadair yn thema sy’n clymu’r cyfan ynghyd.” Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Ynys Môn. Dywedodd Yr Athro Peredur Lynch yn ei feirniadaeth, ‘ Nid bardd y cynganeddu trystfawr a chyhyrog yw Am Ryw Hyd ond bardd y myfyrdod tawel a cheir ganddo lawer o berlau.’ Yr Englyn Credai Huw Meirion Edwards bod gwaith Annes yn dangos Mam tystiolaeth o waith ‘crefftwr cymen a luniodd deyrnged sy’n ffrwyth Ei dawn sy’n siôl amdani, gair addfwyn myfyrdod deallus ar y dyn (Gwyn Thomas) a’i waith.’ yn gwtsh greddfol ynddi, fel ei hanwes drwy dresi Mae Emyr Lewis yn dyfynnu rhan o’i gwaith lle mae’n dweud am ei aur ei dol. -

Election Cycle 2015/16 Guidance Notes for Proposers and Candidates

Election to Fellowship | Election Cycle 2015/16 Guidance Notes for Proposers and Candidates Proposers and Candidates are advised that: 1. The Candidate must be nominated by TWO Fellows: a Lead Proposer and a Seconding Proposer. A list of current Fellows is appended. 2. In order to help correct the under-representation of women in the Fellowship, Fellows are permitted to act as the Lead Proposer for three NEW candidates only each election cycle. However, the nomination of female candidates is exempt from this restriction. 3. All nominations must include: a completed Summary Statement of Recommendation (to include the Candidate’s name, the text of the Statement, the Lead Proposer’s name and signature, and the name of the Seconding Proposer; a completed Summary Curriculum Vitae for the Candidate (to be signed by both the Candidate and the Lead Proposer); and one completed Seconding Proposer Form. 4. These, together with Referees’ reports (see paragraph 12, below), are the only documents that will be used by the Society in considering the nomination. No unsolicited additional materials, references or letters of support will be accepted as part of the nomination. It is therefore imperative that all the relevant sections of the documents are completed as fully as possible. 5. It is the overall responsibility of the Lead Proposer to formulate and present the case for election and to collate all of the relevant forms for submission to the Society. The Lead Proposer must complete the Summary Statement of Recommendation and the Summary Curriculum Vitae; the Seconding Proposer is responsible for completing a Seconding Proposer’s Form and sending it to the Lead Proposer in electronic form (WORD, pdf or scanned). -

Annual Report 2012 - 2013

Annual Report 2012 - 2013 Wales Higher Education Libraries Forum WHELF (Wales Higher Education Libraries Forum) is a collaborative group of all the higher education libraries in Wales, together with the National Library of Wales and the Open University. It is chaired by the Chief Executive and Librarian of the National Library of Wales and its members include Directors of Information Services and Heads of Library Services. WHELF actively promotes the work of higher education libraries in Wales and provides a focus for the development of new ideas and services. WHELF’s mission is to promote collaboration in library and information services, seek cost benefits for shared and consortial services, encourage the exchange of ideas, provide a forum for mutual support and help facilitate new initiatives in library, archives and information service provision. Benefits of WHELF • Raises the profile and value of services and developments in Welsh HE library, archives and information services in our own institutions, in Wales and beyond; • Influences policy makers and funders on matters of shared interest; • Provides cost benefits with regard to shared services, collaborative deals and service developments; • Implements collaborative services and developments for the mutual benefit of member institutions and their users; • Works with other organisations, sectors and domains in support of the development of a cooperative library network in Wales and the UK; • Builds on the collaboration, partnership and advocacy role that WHELF has within Wales and -

Cultural Profile Resource: Wales

Cultural Profile Resource: Wales A resource for aged care professionals Birgit Heaney Dip. 13/11/2016 A resource for aged care professionals Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Location and Demographic ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Everyday Life ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Etiquette ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Cultural Stereotype ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 Family ............................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Marriage, Family and Kinship .......................................................................................................................................... 8 Personal Hygiene ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Www .Llgc.Org.Uk Peter Hain Papers

0 10 0 10 The Welsh 0 10 Political Archive 0 The Welsh Political Archive Newsletter | Autumn 2008 | Number 39 | ISSN 1365-9170 www.llgc.org.uk 10 Peter Hain papers international issues from the 1970s. Peter Hain papers There are many papers deriving from Rhoi Cymru’n Gyntaf The Welsh Political Archive was the activities of the Young Liberals delighted to receive recently a very in the 1970s, including conference Dr W. R. P. George Papers large archive of the papers of the papers and many publications. Right Honourable Peter Hain, the Later papers concern electoral reform, Labour MP for Neath. Cardiff Business Club lectures the trades unions, election campaigns, Born in Nairobi, Kenya, Mr Hain and the evolution of the Labour Party Lloyd George Diary was brought up in South Africa in the 1980s. The last-named group and educated at Pretoria Boys’ includes many of Mr Hain’s keynote Cynhaeaf hanner canrif High School, until his anti-apartheid speeches. There are also more recent parents were forced to leave the papers relating to the Labour Party Sleeping with the enemy country. He later obtained degrees in the new millennium, the cabinet at Queen Mary College, London and positions held by Mr Hain, together Lord Pontypridd papers Sussex University. Originally a ‘Young with large groups of press cuttings Liberal’, he joined the Labour Party in and research papers connected Sir J. Herbert Lewis papers 1977 and served as research officer of with the donor’s books and articles. the Union of Communication Workers Further important documents are also Dr E. -

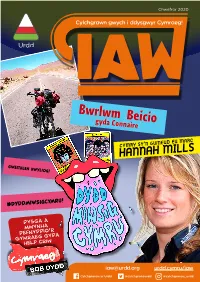

Bwrlwm Beicio Gyda Connaire

Chwefror 2020 Cylchgrawn gwych i ddysgwyr Cymraeg! Bwrlwm Beicio gyda Connaire Gweithlen hwyliog! #DyddMiwsigCymru! Dysga a mwynha defnyddio’r Gymraeg gyda help criw [email protected] urdd.cymru/iaw Cylchgronau yr Urdd @cylchgronaurdd @cylchgronau_urdd Geirfa: hufen iâ - ice cream Mis Chwefror hapus i chi a doubt dyddiadur - diary teledu - tv awyr agored - outdoors ddarllenwyr IAW! Mae dau grawnfwyd - cereal anhygoel - incredible siwgr - sugar yn ddiweddarach - later on nawr ac yn y man - now and berson ifanc o Ysgol Gyfun ar y cyfan - on the whole y lolfa - the living room again Trefynwy wedi ysgrifennu ysblennydd - splendid amser egwyl - break time cysgu - to sleep blaenwr - forward (rugby dyddiaduron yn trafod eu ffrwythau - fruit mefus - strawberry ysgytlaeth - milkshake ieithoedd - languages position) hwythnosau. Hefyd, mae adio a lluosi - add and a bod yn onest - to be honest fodd bynnag - however pobl ifanc o Ysgol Uwchradd multiply a dweud y gwir - to tell the ar y llaw arall - on the other Caerdydd wedi mynegi eu cerddoriaeth - music truth hand digrif - funny tywysogion - princes coginio - cooking barn am eu hoff bethau a oren - orange tŵr - tower rhaglenni. sur - sour beth bynnag - whatever anghytuno - to disagree dychrynllyd - frightful pos - puzzle soffistigedig - sophisticated Beth wyt ti’n gwneud yn blasus - tasty straeon - stories gwastraff amser - a waste of ystod yr wythnos? Beth yw dy ardderchog - excellent llawn dychymyg - full of time uwd - porridge imagination anghredadwy - unbelievable farn di am raglenni Cymraeg? mêl - honey arlunio - to draw enillon ni - we won brechdan - sandwich operâu sebon - soap operas Anfona lythyr atom ni at cyw iâr - chicken yn enwedig - especially natur - nature [email protected] ymolchais - I washed cig moch - bacon actio - acting ymlaciol - relaxing cur pen - headache i ddweud y gwir - to tell the cinio rhost - roast dinner diodydd pefriog - fizzy drinks truth llysiau - vegetables yn gynnar - early cig - meat heb os nac oni bai - without fodd bynnag - however Annwyl Iaw, hefyd.