L'abecedaire De Gilles Deleuze, Avec Claire Parnet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Training's Ability to Improve Other Race Individuation

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2013 Recognizing the Other: Training's Ability to Improve Other Race Individuation W. Grady Rose Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Rose, W. Grady, "Recognizing the Other: Training's Ability to Improve Other Race Individuation" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 47. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/47 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: RECOGNIZING THE OTHER 1 RECOGNIZING THE OTHER: TRAINING’S ABILITY TO IMPROVE OTHER RACE INDIVIDUATION by W. GRADY ROSE (Under the Direction of Amy Hackney, Ph. D.) ABSTRACT Members of one race or ethnicity are less able to individuate members of another race compared to their own race peers. This phenomenon is known as the other race effect (ORE) or the cross race effect (CRE). Not only are individuals less able to identify members of the other race but they are also more likely to pick those individuals out of a crowd. The categorization- individuation model predicts that this deficit arises from a lack of motivated individuation; in which members of the other race are remembered at the category level as a prototype while own race members are remembered by name with individual characteristics. -

The Dawn in Erewhon"

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences December 2007 Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon" Patrick Dillon [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Recommended Citation Dillon, Patrick, "Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon"" 10 December 2007. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23. Revised version, posted 10 December 2007. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon" Abstract In "The Dawn in Erewhon", the concluding novella of Tatlin!, Guy Davenport explores the myth of Orpheus in the context of two storylines: Adriaan van Hovendaal, a thinly veiled version of Ludwig Wittgenstein, and an updated retelling of Samuel Butler's utopian novel Erewhon. Davenport tells the story in a disjunctive style and uses the Orpheus myth as a symbol to refer to a creative sensibility that has been lost in modern technological civilization but is recoverable through art. Keywords Charles Bernstein, Bernstein, Charles, English, Guy Davenport, Davenport, Orpheus, Tatlin, Dawn in Erewhon, Erewhon, ludite, luditism Comments Revised version, posted 10 December 2007. This article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23 Dimensions of Erewhon The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport’s “The Dawn in Erewhon” Patrick Dillon Introduction: The Assemblage Style Although Tatlin! is Guy Davenport’s first collection of fiction, it is the work of a fully mature artist. -

Becoming-Other: Foucault, Deleuze, and the Political Nature of Thought Vernon W

Philosophy Faculty Publications Philosophy 4-2014 Becoming-Other: Foucault, Deleuze, and the Political Nature of Thought Vernon W. Cisney Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/philfac Part of the Philosophy of Mind Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cisney, Vernon W. "Becoming-Other: Foucault, Deleuze, and the Nature of Thought." Foucault Studies 17 Special Issue: Foucault and Deleuze (April 2014). This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/philfac/37 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Becoming-Other: Foucault, Deleuze, and the Political Nature of Thought Abstract In this paper I employ the notion of the ‘thought of the outside’ as developed by Michel Foucault, in order to defend the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze against the criticisms of ‘elitism,’ ‘aristocratism,’ and ‘political indifference’—famously leveled by Alain Badiou and Peter Hallward. First, I argue that their charges of a theophanic conception of Being, which ground the broader political claims, derive from a misunderstanding of Deleuze’s notion of univocity, as well as a failure to recognize the significance of the concept of multiplicity in Deleuze’s thinking. From here, I go on to discuss Deleuze’s articulation of the ‘dogmatic image of thought,’ which, insofar as it takes ‘recognition’ as its model, can only ever think what is already solidified and sedimented as true, in light of existing structures and institutions of power. -

Introduction Part I Deleuze and Systematic Philosophy

Notes Introduction 1. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane (New York: Viking, 1977), p. 240. 2. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi. (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), p. 3. 3. Gilles Deleuze, Negotiations, trans. Martin Joughin. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), pp. 88–89. 4. Gilles Deleuze, Empiricism and Subjectivity: An Essay on Hume’s Theory of Human Nature, trans. Constantine Boundas (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), p. 107. 5. Ibid., p. 106. 6. Henri Bergson, The Creative Mind, trans. Mabelle L. Andison (New York: Philosophical Library, 1946), pp. 21–28. 7. Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), p. 8. Part I Deleuze and Systematic Philosophy 1. Gilles Deleuze, Negotiations (1972–1990), trans. Martin Joughin (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), p. 31. 2. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), p. 18. 3. Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton (New York: Columbia University Press), pp. 170–6. 4. Gilles Deleuze, Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza, trans. Martin Joughin (New York: Zone Books, 1992). This logic of expression is developed in chapters 1–2 and 6–8. 5. Spinoza brings together the notion of substance and expression in Part 1 of the Ethics: definitions 4 and 6, Proposition 10, and the Scholium following Proposition 10. The treatment of modifications and individuals first appears in Part 2, Proposition 7 along with its Corollary and Scholium. -

Affect, Trust, and Dignity: Ontological Possibilities and Material Consequences for a Philosophy of Educational Resonance Walter Gershon Kent State University

Walter Gershon 461 Affect, Trust, and Dignity: Ontological Possibilities and Material Consequences for a Philosophy of Educational Resonance Walter Gershon Kent State University INTRODUCTION This essay articulates a philosophy of resonance in education, from some of its theoretical possibilities through their material consequences. Contemporary under- standings in educational philosophy have a tendency to utilize ocular metaphors, epistemological constructions that provide frames for seeing the world. There are at least the following three difficulties with such a reliance on the ocular. First, they are easily interrupted by nonocular metaphors. While this may seem to be a rather surface concern, it points to a deep philosophical set of problems. For example, what happens when the augenblick, a construct around which much philosophizing has been accomplished, is pressed slightly to become a “blink of an ear”?1 This move not only questions the veracity of ocular-centric constructions from blinks to texts — for what does it say about an idea if it falls apart by shifting senses — but it also presses at the feasibility of framing, its inherently bounded nature as well as the large number of possibilities excluded by its gaze. Second, the sonic provides another avenue for wonder. Sound is omnipresent and questions of hearing or listening are as much about physical anatomy as they concern sociocultural constructs about what sounds can mean. Unlike sight that is necessarily directional and constantly interrupted (for example, by blinking), sound is omnidirectional, creating a context in which focus requires a particular kind of attentive filtering rather than a reframing or panning directionality. Finally, sound is and always has been. -

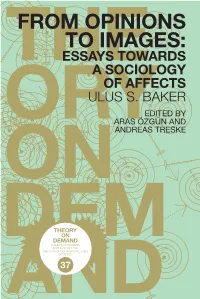

From Opinions to Images: Essays Towards a Sociology of Affects Ulus S

FROM OPINIONS TO IMAGES: ESSAYS TOWARDS A SOCIOLOGY OF AFFECTS ULUS S. BAKER EDITED BY ARAS ÖZGÜN AND ANDREAS TRESKE A SERIES OF READERS PUBLISHED BY THE INSTITUTE OF NETWORK CULTURES ISSUE NO.: 37 FROM OPINIONS TO IMAGES: ESSAYS TOWARDS A SOCIOLOGY OF AFFECTS ULUS S. BAKER EDITED BY ARAS ÖZGÜN AND ANDREAS TRESKE FROM OPINIONS TO IMAGES 2 Theory on Demand #37 From Opinions to Images: Essays Towards a Sociology of Affects Ulus S. Baker Edited by Aras Özgün and Andreas Treske Cover design: Katja van Stiphout Design and EPUB development: Eleni Maragkou Published by the Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, 2020 ISBN print-on-demand: 978-94-92302-66-3 ISBN EPUB: 978-94-92302-67-0 Contact Institute of Network Cultures Phone: +31 (0)20 595 1865 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.networkcultures.org This publication is available through various print on demand services. EPUB and PDF edi- tions are freely downloadable from our website: http://www.networkcultures.org/publications. This publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer- cial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International. FROM OPINIONS TO IMAGES 3 Cover illustration: Diagram of the signifier from Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 1987. 4 THEORY ON DEMAND CONTENTS PASSING THROUGH THE WRITINGS OF ULUS BAKER 5 1. A SOCIOLOGY OF AFFECTS 9 2. WHAT IS OPINION? 13 3. WHAT IS AN AFFECT? 59 4. WHAT IS AN IMAGE? 86 5. TOWARDS A NEO-VERTOVIAN SENSIBILITY OF AFFECTS 160 6. ON CINEMA AND ULUS BAKER 165 BIBLIOGRAPHY 180 BIOGRAPHIES 187 FROM OPINIONS TO IMAGES 5 We have lived at least one century within the idea of opinion which determined some of the major themes in social sciences.. -

Reason, Desire, and the Will: in Defense of a Tripartite Moral Psychology

Reason, Desire, and the Will: In Defense of a Tripartite Moral Psychology By Jeremy Carey A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Hannah Ginsborg, Co-Chair Professor R. Jay Wallace, Co-Chair Professor Kinch Hoekstra Summer 2017 Abstract Reason, Desire, and the Will: In Defense of a Tripartite Moral Psychology by Jeremy Carey Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy University of California, Berkeley Professor R. Jay Wallace, Co-Chair Professor Hannah Ginsborg, Co-Chair Which aspects of our psychology are most central to explaining our intentional actions, and how should we conceive of them in light of their abilities to play those explanatory roles? These are key questions in moral psychology, and my dissertation tries to answer them, or at least to provide a beginning. As with much else in philosophy, the basic contours of this debate first came to us in Plato. Though I am not primarily concerned with the historical details, the initial argument of the dissertation and its distinctive approach reflect these Platonic origins in an interesting way. In Plato’s Protagoras, he presents Socrates as having an intellectualist moral psychology; that is, as claiming that all intentional action is motivated by a belief about what is best. This leads him to argue against the possibility of weakness of will. Plato himself later rejected this view, most notably in the Republic. There he argued that properly accounting for psychological conflict required dividing the soul into three “parts” - rational, spirited, and appetitive. -

Affect Theory As a Methodology for Design

Affect Theory as a Methodology for Design Author Nandita Baxi Sheth & Kristopher Holland University of Cincinnati, College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning In Ordinary Affects (2010), Katherine Stewart, writes, Affect is the commonplace, labor-intensive process of sensing modes of living as they come into being. It hums with the background noise of obstinacies and promises, ruts and disorientations, intensities and resting points. It stretches across real and imaginary social fields and sediments, linking some kind of everything (p. 340). ‘Linking some kind of everything’, affects are intensities, resonances, force fields that exist and travel in in between bodies and spaces. Affect shines a light on what happens in that unknowable space that is the gap between an event and its cognitive signification. These embodied intensities occur through the automatic functions of our bodies--the membrane of the skin, the beating of the heart, and the rhythm of the breath (Massumi, 2002, p. 26). Imaginative Interlude: Imagine if you will an experience of awe or wonder—such as the much clichéd sunset on the beach. The salty smell in the air. The changing temperature of the skin as the sun’s warmth dissipates The ever so gradual color changes in the sky The liquid melding of sky and sea at the horizon line The rhythmic sounds of moving water There is gap, fractions of second, between the body’s experience of this event and the application of language to label that experience. Thinking about this gap- between experience itself and representation of that experience is the space of inquiry that is explored by Affect Theory. -

Summa Theologiae with Reference to Contemporary Psychological Studies

Concept of Happiness in Summa Theologiae with Reference to Contemporary Psychological Studies Von der Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Duisburg-Essen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Dissertation von Jaison Ambadan Chacko Ambadan aus Areekamala, Kerala, Indien Erster Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ralf Miggelbrink Zweiter Gutachter : Prof. Dr. Markus Tiwald Vorsitzender des Prüfungsausschusses: Prof. Dr. Neil Roughley Tag der Disputation: 02.07.2018 1 Concept of Happiness in Summa Theologiae with Reference to Contemporary Psychological Studies General Introduction 6 Chapter I The Ethical Perspective of Happiness in Aquinas´s Concept of Human Acts Introduction 27 1. Human Acts 31 1.1 Voluntary 52 1.2 Involuntary 53 1.3 Circumstances 54 1.3.1 Nature of Circumstance 55 1.3.2 Role Circumstances in Moral Evaluation 56 1.4 Cognitive Participation 57 1.4.1 Three Acts of the Speculative Intellect 58 1.4.2 Three Acts of the Practical Intellect 60 1.5 The Will 62 1.5.1 Cause of the Movement of the Will 62 1.5.2 Manner in which the Will Moves 63 1.5.3 Characteristics of the Act of the Will 64 1.5.3.1 Enjoyment 65 1.5.3.2 Intention 65 1.5.3.3 Choice 67 1.5.3.4 Counsel 68 1.5.3.5 Consent 68 1.5.3.6 Use 69 1.6 Human Acts Commanded by the Will 70 1.6.1 Good and Evil in Human Acts 71 1.6.2 Goodness and Malice in Human Acts 72 1.6.3 Impact of the Interior Act 75 1.6.4 Impact of the External Act 76 1.6.5 Impact of Disposition 77 Conclusion 79 2 Chapter II Thomas Aquinas´s Cognition of Passion and Happiness Introduction 82 2. -

Dark Deleuze

Forerunners: Ideas First from the University of Minnesota Press Original e-works to spark new scholarship FORERUNNERS IS A thought-in-process series of breakthrough digital works. Written between fresh ideas and finished books, Forerunners draws on scholarly work initiated in notable blogs, social media, conference plenaries, journal articles, and the synergy of academic exchange. This is gray literature publishing: where intense thinking, change, and speculation take place in scholarship. Ian Bogost The Geek’s Chihuahua: Living with Apple Andrew Culp Dark Deleuze Grant Farred Martin Heidegger Saved My Life John Hartigan Aesop’s Anthropology: A Multispecies Approach Akira Mizuta Lippit Cinema without Reflection: Jacques Derrida’s Echopoiesis and Narcissism Adrift Reinhold Martin Mediators: Aesthetics, Politics, and the City Shannon Mattern Deep Mapping the Media City Jussi Parikka The Anthrobscene Steven Shaviro No Speed Limit: Three Essays on Accelerationism Sharon Sliwinski Mandela’s Dark Years: A Political Theory of Dreaming Dark Deleuze Dark Deleuze Andrew Culp University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis Dark Deleuze by Andrew Culp is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published by the University of Minnesota Press, 2016 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. Contents Abbreviations Introduction The Extinction of Being Advancing toward Nothing Breakdown, -

Disrupting Ethnography Through Rhizoanalysis Diana Masny1

Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://qre.hipatiapress.com Disrupting Ethnography through Rhizoanalysis Diana Masny1 1) Educational Department, Université d'Ottawa (Canada) / Queensland University of Technology (Australia). Date of publication: October 28th, 2014 Edition period: June 2012-October 2014 To cite this article: Masny, D. (2014) Disrupting Ethnography through Rhizoanalysis. Qualitative Research in Education, 3(3) 345-363. doi: 10.4471/qre.2014.51 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.4471/qre.2014.51 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). Qualitative Research in Education Vol.3 No.3 October 2014 pp. 345-363 Disrupting Ethnography through Rhizoanalysis Diana Masny Université d'Ottawa / Queensland University of Technology (Received: 29 May 2014; Accepted: 2 September 2014; Published; 28 October 2014) Abstract This article interrogates principles of ethnography in education proposed by Mills and Morton: raw tellings, analytic pattern, vignette and empathy. This article adopts a position that is uncomfortable, unconventional and interesting. It involves a deterritorialization/ rupture of ethnography in education in order to reterritorialize a different concept: rhizoanalysis, a way to position theory and data that is multi- layered, complex and messy. Rhizoanalysis, the main focus of this article is not a method. It is an approach to research conditioned by a reality in which Deleuze and Guattari disrupt representation, interpretation and subjectivity. In this article, Multiple Literacies Theory, a theoretical and practical framework, becomes a lens to examine a rhizomatic study of a Korean family recently arrived to Australia and attending English as a second language classes. -

The Ontological Plurality of Digital Voice: a Schizoanalysis of Rate My Professors and Rate My Teachers

The ontological plurality of digital voice: a schizoanalysis of Rate My Professors and Rate My Teachers This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of a paper published in Principles of transversality in globalization and education: Mayes, Eve 2018, The ontological plurality of digital voice: a schizoanalysis of Rate My Professors and Rate My Teachers. In Cole, David R and Bradley, Joff PN (ed), Principles of transversality in globalization and education, Springer, Singapore, pp.195-210. The final authenticated version is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0583- 2_12 This is the accepted manuscript. ©2018, Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. Reprinted with permission. Downloaded from DRO: http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30105103 DRO Deakin Research Online, Deakin University’s Research Repository Deakin University CRICOS Provider Code: 00113B Book: Principles of Transversality in Globalization and Education The ontological plurality of digital voice: A schizoanalysis of Rate My Professors and Rate My Teachers Eve Mayes Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria, Australia Abstract Online evaluations (like Rate My Professors and Rate My Teachers) have been celebrated as forming wider publics and modes of accountability beyond the institution, and critiqued as reinforcing consumeristic pedagogical relations. This chapter takes up the websites Rate My Professors and Rate My Teachers as empirical entry points to a conceptual discussion, after Félix Guattari, of the ontological plurality of digital voice, and its associated refrains and universes of reference. I turn attention from analysis of the effects of these digitized student evaluations to the moment of their formation – for example, when a student’s finger clicks on a particular star rating.