Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top 15 Lgus with Highest Poverty Incidence, Davao Region, 2012)

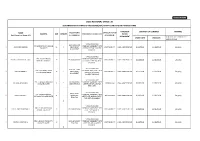

Table 1. City and Municipal-Level Small Area Poverty Estimates (Top 15 LGUs with Highest Poverty Incidence, Davao Region, 2012) Rank Province Municipality Poverty Incidence (%) 1 Davao Occidental Jose Abad Santos (Trinidad) 75.5 2 Davao Occidental Don Marcelino 73.8 3 Davao del Norte Talaingod 68.8 4 Davao Occidental Saragani 65.9 5 Davao Occidental Malita 60.8 6 Davao Oriental Manay 58.1 7 Davao Oriental Tarragona 56.9 8 Compostela Valley Laak (San Vicente) 53.8 9 Davao del Sur Kiblawan 52.9 10 Davao Oriental Caraga 51.6 11 Davao Occidental Santa Maria 50.7 12 Davao del Norte San Isidro 43.2 13 Davao del Norte New Corella 41.6 14 Compostela Valley Montevista 40.2 15 Davao del Norte Asuncion (Saug) 39.2 Source: Philippine Statistics Authority Note: The 2015 Small Area Poverty Estimates is not yet available. Table 2. Geographically-Isolated and Disadvantaged Areas (GIDAs) PROVINCE/HUC CITY/MUNICIPALITY BARANGAYS Baganga Binondo, Campawan, Mahan-ob Boston Caatihan, Simulao Caraga Pichon, Sobreacrey, San Pedro Cateel Malibago Davao Oriental Gov. Generoso Ngan Lupon Don Mariano, Maragatas, Calapagan Manay Taokanga, Old Macopa Mati City Langka, Luban, Cabuaya Tarragona Tubaon, Limot Asuncion Camansa, Binancian, Buan, Sonlon IGaCoS Pangubatan, Bandera, San Remegio, Libertad, San Isidro, Aundanao, Tagpopongan, Kanaan, Linosutan, Dadatan, Sta. Cruz, Cogon Davao del Norte Kapalong Florida, Sua-on, Gupitan San Isidro Monte Dujali, Datu Balong, Dacudao, Pinamuno Sto. Tomas Magwawa Talaingod Palma Gil, Sto. Niño, Dagohoy Laak Datu Ampunan, Datu Davao Mabini Anitapan, Golden Valley Maco Calabcab, Elizalde, Gubatan, Kinuban, Limbo, Mainit, Malamodao, Masara, New Barili, New Leyte, Panangan, Panibasan, Panoraon, Tagbaros, Teresa Maragusan Bahi, Langgawisan Compostela Valley Monkayo Awao, Casoon, Upper Ulip. -

Rapid Market Appraisal for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao Del Sur (Brackishwater Areas)

Rapid Market Appraisal for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) AMC MINI PROJECT: TEAM TILAPIA Acuna, Thaddeus R., UP Mindanao Almazan, Cynthia V., DOST-PCAARRD Castillo, Monica, DOST-PCAARRD Romo, Glory Dee A., UP Mindanao Rosetes, Mercy A., Foodlink Advocacy Co-operative (FAC) RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) OBJECTIVE To conduct a market assessment of expanding areas for tilapia culture production in costal and brackishwater areas in the province of Davao del Sur. RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) RESEARCH QUESTIONS 1. Does consumption level of Tilapia a key contributing factor for potential expansion of Tilapia production in Davao del Sur? 2. Is the market potential of competitiveness of Tilapia substantial enough to revitalize tilapia production in Davao del Sur? RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) METHODOLOGY RAPID APPRAISAL APPROACH Secondary data Encoding Market Areas for gathering Constraints Intervention Primary data Market gathering Competitiveness * KIs Market * Market Mapping Opportunities * Market Visits A Step-by step approach of Rapid Market Appraisal (Adapted from the RMA proposal for underutilized fruits) RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) INDUSTRY SITUATION ✓ Tilapia is a major aquaculture product in the Philippines that is considered important to the country’s food security and nutrition (Perez, 2017) ✓ Most -

Coastal Environmental Profile of the Malalag Bay Area Davao Del Sur, Philippines

i COASTAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE OF THE MALALAG BAY AREA DAVAO DEL SUR, PHILIPPINES IMELDA S. VALLE MA. CHONA B. CRISTOBAL ALAN T. WHITE EVELYN DEGUIT Coastal Resource Management Project of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources supported by the United States Agency for International Development 2000 ii Coastal Environmental Profile of the Malalag Bay Area, Davao del Sur, Philippines Imelda S. Valle, Ma. Chona B. Cristobal, Alan T. White and Evelyn T. Deguit 2000 PRINTED IN CEBU CITY, PHILIPPINES Citation: Valle, I.S., M.C.B. Cristobal, A.T. White and E. Deguit. 2000. Coastal Environmental Profile of the Malalag Bay Area, Davao del Sur, Philippines. Coastal Resource Management Project, Cebu City, Philippines, 127 p. This publication was made possible through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms and conditions of Contract No. AID-492-C-00-96-00028-00 supporting the Coastal Resource Management Project (CRMP). The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID. This publication may be reproduced or quoted in other publications as long as proper reference is made to the source. Production: Letty Dizon copy-edited and Lume Inamac and Ida Juliano word-processed, did the layout, and designed the cover of this document. Cover Photos: Front - A. White; Back - CRMP staff. CRMP Document No. 23-CRM/2000 ISBN 971-92289-9-7 iii CONTENTS Tables and Figures v Foreword vii Preface viii Acknowledgments x Acronyms and Abbreviations xi Commonly Used Local Terms xii Glossary of Terms xiv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Physical Features 7 Land Area 7 Topography 7 Hydrology 9 Soil 14 Land Uses 14 Climate 16 Chapter 3 Natural Resources 17 Mineral Resources 17 Forest Resources 17 Coastal Resources 18 Hagonoy 20 Malalag 23 Padada 26 Sta. -

E1467 V 12 REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT of PUB1,IC WORKS and HIGHWAYS BONIFACIO DRIVE, PORT AREA, MANILA

E1467 v 12 REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUB1,IC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS BONIFACIO DRIVE, PORT AREA, MANILA Public Disclosure Authorized FEASIBILITY STUDIES AND DETAILED ENGINEERING DESIGN OF REMEDIAL WORKS IN SPECIFIED LANDSLlDE AREAS AND ROAD SLIP SECTlONS IBRD-Assisted National Road Improvement and Management Program Loan No. 7006-PH Draft Final Report on the Environmental and Social Components DIGOS-GENERAL SANTOS ROAD Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized I Davao - Cal~nanRoad .#ha--#K*I Public Disclosure Authorized JAPAN OVERSEAS COlYSULTANTS CO, LTIk In association with ClRTEZ* DBYILOPYBYT CORPOMTlOW @ TECWNIKS GROUP CORPORATION REPUBLlC OF THE PHlLIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS BONIFAClO DRIVE, PORT AREA, MAhllLA FEASIBILITY STUDIES AND DETAILED ENGINEERING DESIGN OF REMEDIAL WORKS IN SPECIFIED LANDSLIDE AREAS AND ROAD SLIP SECTIONS IBRD-Assisted National Road Improvement and Management Program Loan No. 7006-PH Draft Final Report on the Environmental and Social Components DIGOS-GENERAL SANTOS ROAD Cebu Transcentral Road in association with CERIQA DeMLOCYENT COlMRATMN O) TECHMIKS GROUP CORPORATlOM TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE KEY MAP DIWS GENERAL SANTOS ROAD Figure 1-1 1.0 GENERAL STATEMENT 1-1 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS 2.1 Location 2.2 Objectives 2.3 Coverage and Scope 3.0 ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ROAD INFLUENCE AREA 3.1 Local Geography and Landuse 3.2 Topography and Climate 3.3 Soil Types 4.0 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC PROFILES OF THE ROAD IMPACT AREA 4.1 Davao del Sur Road Segment 4.2 Sarangani Road Segment 4.3 General Santos City Road Segment 5.0 ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCNMANAGEMENT PLAN (Em) Construction Related Impacts Operation Related Impacts Environmental Compliance Requirement Waste Management and Disposal Strategy Contingency Response Strategy Abandonment Strategy Environmental Monitoring Strategy Construction Contractor's Environmental Program Table of Contents: cont 'd.. -

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support I. REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Davao Region still needs to improve its infrastructure facilities and services. While the Davao International Airport has been recently completed, road infrastructure, seaport, and telecommunication facilities need to be upgraded. Flood control and similar structures are needed in flood prone areas while power and water supply facilities are still lacking in the region’s remote and underserved areas. While the region is pushing for increased production of staple crops, irrigation support facilities in major agricultural production areas are still inadequate. Off-site infrastructure in designated tourism and agri-industrial areas are likewise needed to encourage investment and spur economic activities. Accessibility and Mobility through Transport There is a need for the construction of new roads and improvement of the existing road network to provide better access and linkage within and outside the Region as an alternate to existing arterial and local roads. The lack of good roads in the interior parts of the municipalities and provinces connecting to major arterial roads constrains the growth of agriculture and industry in the Region; it also limits the operations of transport services due to high maintenance cost and longer turnaround time. Traffic congestion is likewise becoming a problem in highly urbanized and urbanizing areas like Davao City and Tagum City. While the Region is physically connected with the adjoining regions in Mindanao, poor road condition in some major highways also hampers inter-regional economic activities. The expansion of agricultural activities in the resettlement and key production areas necessitates the opening and construction of alternative routes and farm-to-market roads. -

To Pula Tana Visring Deck Del Sur, Hereinafter Refered to As The

Departsnent of public Works and Highways Contract ID : 2OLElXll4 Contract Name : Crnstruction of Concrete Road - Access Road leading to Pula Tana Visring Deck Location of the Contract : Kiblawan, Davao del Sur FORM OF CONIRACT AGREEMENT IG{OWAI-t I,IEN BYTHESE PRESENTS: This CONTRACT AGREEMENT, made this 13h day of February 2o2o by and between: The GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBUC OF THE PHILIPPINES through the Ilepartment of pubric rf,orks and Highways (DpwH) represented nerlin uy NICOMEDES D. PARILIA, rR. - District Engineer, duly authorized for this purp*, with main office address at Lapu-tapu Skeet, Barangay Zone 3, Digos City, Davao del Sur, hereinafter refered to as the.pRocunfffe eiffffV.; -and- tt{AGAR CONSTRUCTION AI{D SUppLy, a singte proprietorship organized existing under and by virtue of raws phirippines, of the Repubric of the with main office address at 138, Joehua St., Villa park Subd., Catrartian, Davao City, represented herein by MARITEST. GARCTNES propri*r/Manager, - duly authorizedfor this purpose, hereinafter referred to as the.COIITRACTOR.; II'ITNESSETH WHEREAS, the pRocuRr[c ENTrry is desirous that the coNTRAcroR execute the works under contract rD No. 20LD0014 - Construction of concr€te Road Access Road leading pura Tana - to viodng Decrg Kibrawan, Davao det Sur, hereinafter called the'works", and the pRocuRrNG ENTrry has accepted the carcurated Bid of the coNTRAcroR for the execution and compretion of the works at the carcurated unit bid prices shown in the atbched Bi[ of euantities, or a totar contract price of trrine Miflion Five Hundred Six Thousand pesos Only (p 1506,000.00). Now, THEREFORE, for and consideration of the foregoing premises, the parties hereto agree as follows: 1 In this COITTRACT AGREEMEIIT, words and expressions shall have the same meanings as are respectivery assigned to them in the conditions of contract hereinafter referred to. -

Dole Regional Office Xi Government Internship Program (Gip) Beneficiaries Monitoring Form

DOLE-GIP_Form C DOLE REGIONAL OFFICE XI GOVERNMENT INTERNSHIP PROGRAM (GIP) BENEFICIARIES MONITORING FORM NATURE OF DURATION OF CONTRACT REMARKS NAME EDUCATIONAL OFFICE/PLACE OF ADDRESS AGE GENDER DOCUMENTS SUBMITTED WORK/ (Last Name, First Name, MI) ATTAINMENT ASSIGNMENT ASSIGNMENT (e.g. Contract completed or START DATE END DATE preterminated *APPLICATION FORM BS IN HOTEL AND 678, MANGUSTAN ST., MADAUM, *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 1 ALIVIO, FEMAE JEAN B. 23 F RESTAURANT W/IN TAGUM CITY CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going TAGUM CITY CERTIFICATE *TOR *ACCIDENT MANAGEMENT INSURANCE *APPLICATION FORM PRK. 19-B, KATIPUNAN, *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 2 BALIENTES, MARIA KATHLEEN G. 20 F BS IN ACCOUNTING W/IN TAGUM CITY CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going MADAUM, TAGUM CITY CERTIFICATE *SPR *ACCIDENT INSURANCE *APPLICATION FORM BS IN HOTEL AND PRK. 5-A, APOKON, TAGUM *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 3 CANTILA, GEBBIE M. 20 F RESTAURANT W/IN TAGUM CITY CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/19/2018 11/17/2018 On going CITY, DAVAO DEL NORTE CERTIFICATE *DIPLOMA MANAGEMENT *ACCIDENT INSURANCE *APPLICATION FORM PRK. 1, TANGLAW, BE DUJALI, BS IN BUSINESS *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 4 ESTAÑOL, ANNA MAE D. 21 F W/IN BE DUJALI CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going DAVAO DEL NORTE ADMINISTRATION CERTIFICATE *DIPLOMA/TOR *BRGY. CERT *APPLICATION FORM BACHELOR OF PRK. 4, NARRA, GABUYAN, *INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT *BIRTH 5 LOPEZ, MARYJAN P. 23 SECONDARY W/IN KAPALONG CHILD LABOR PROFILER 6/18/2018 11/16/2018 On going KAPALONG, DAVAO DEL NORTE CERTIFICATE *MARRIAGE CERT., EDUCATION *TOR *CERT OF INDIGENCY M *APPLICATION FORM PRK. -

Sitecode Region Penro Cenro Barangay Municipality Name of Organization Contact Person Commodity Hectares

AREA IN SITECODE REGION PENRO CENRO BARANGAY MUNICIPALITY NAME OF ORGANIZATION CONTACT PERSON COMMODITY HECTARES Ancestral Domain Tribal Farmers Bamboo, Cacao, Fruit XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Upper Ulip Monkayo Association Mauricio Latiban Trees, Rubber, Timber 75 Barangay Tribal Council of Elders & Leaders Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo San Jose Monkayo of San Jose (BTCEL San Jose) Romeo Capao Rubber, Timber 50 Camanlangan Tree Growers Association Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Camanlangan New Bataan (CATREGA) Ruperto Sabay Sr. Timber 50 Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Casoon Monkayo Casoon Tree Farmers Association (CATFA) Gavino Ayco Timber 80 Dalaguete Lebanon San Vicente Montevista Watershed Farmers Association Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Lebanon Montevista (DALESANMWFA) Martiniano Paniamogan Timber 37 XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Ngan Compostela Kapwersa Comval Agricultural Cooperative Alejandro Cacao, Timber 50 Magangit Upland Farmers Association Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Fatima New Bataan (MAUFA) Clemente T. Nabor Timber 50 Mangayon Indigenous People and Farmers Cacao, Fruit Trees, XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Mangayon Compostela Association (MIPFA) Timber 70 Maragusan Waterworks & Sanitation Bamboo, Cacao, Fruit XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Poblacion Maragusan Cooperative (MAWASCO) Cesar Escuadro Trees, Timber 100 Mayaon Upland Small Farmers Association Bamboo, Cacao, Fruit XI Compostela Valley Monkayo Mayaon Montevista (MUSFA) -

Davao Occidental

LAND SUITABILITY MAP CASSAVA LAND RESOURCES EVALUATION AND SUITABILITY ASSESSMENT OF STRATEGIC PRODUCTION AREAS PROVINCE OF DAVAO OCCIDENTAL R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S D E PA R T M E N T O F AG R I C U LT U R E BUREAU OF SOILS AND WATER MANAGEMENT SRDC Bldg., Elliptical Road Cor. Visayas Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Tel/Fax No. : (+632) 332-9534 E-mail : bswm [email protected] MAP INDEX LAND RESOURCES EVALUATION AND SUITABILITY ASSESSMENT OF STRATEGIC PRODUCTION AREAS PROVINCE OF DAVAO OCCIDENTAL LEGEND Places BALABAG \ Capital City DIGOS ^ City MATANAO P Capital Town HAGONOY 4014-II ! Town PADADA Padada 4114-III Administrative Boundary KIBLAWAN Basiawan MALALAG SULOP Regional SANTA MARIA Provincial City Municipal Map Index MALITA 4013-I Index grid Kabayawa 4113-IV Malita Topographic Relief MALUNGON Bathymetry DON MARCELINO 4013-II 4113-III Alabel Kalian ALABEL LOCATION MAP MALAPATAN JOSE ABAD SANTOS 4012-I 4112-IV Malapatan Caburan GLAN 4012-II Margus Grande MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION Land suitabilityinformation produced by the Bureau of Soils and Water SARANGANI Management (BSWM) through the Land Resources Evaluation and Suitability Assessment of Strategic Production Areas for Major Commodities Project duly supported by the Philippine Council on 4011-I Agriculture and Fisheries (PCAF) and funded by the Bureau of Agricultural Research (BAR). Sarangani Map produced by the Geomatics and Soil Information Technology Island Division, Bureau of Soils and Water Management (BSWM). Users noting errors or omissions in this publication are requested to inform the Bureau of Soils and Water Management. -

2010 Census of Population and Housing Compostela Valley

2010 Census of Population and Housing Compostela Valley Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population COMPOSTELA VALLEY 687,195 COMPOSTELA 81,934 Bagongon 1,946 Gabi 3,891 Lagab 2,586 Mangayon 4,403 Mapaca 2,082 Maparat 3,445 New Alegria 3,262 Ngan 7,738 Osmeña 4,753 Panansalan 906 Poblacion 26,773 San Jose 5,114 San Miguel 7,354 Siocon 3,266 Tamia 2,621 Aurora 1,794 LAAK (SAN VICENTE) 70,856 Aguinaldo 4,151 Banbanon 1,352 Binasbas 1,127 Cebulida 1,797 Il Papa 1,189 Kaligutan 2,902 Kapatagan 4,461 Kidawa 2,050 Kilagding 2,012 Kiokmay 1,379 Langtud 2,896 Longanapan 2,334 Naga 1,249 Laac (Pob.) 7,150 San Antonio 2,426 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Compostela Valley Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Amor Cruz 2,675 Ampawid 2,633 Andap 1,745 Anitap 505 Bagong Silang 1,063 Belmonte 1,212 Bullucan 1,229 Concepcion 1,114 Datu Ampunan 1,145 Datu Davao 1,031 Doña Josefa 894 El Katipunan 1,140 Imelda 1,996 Inacayan 1,077 Mabuhay 2,298 Macopa 707 Malinao 711 Mangloy 1,299 Melale 1,701 New Bethlehem 601 Panamoren 911 Sabud 1,211 Santa Emilia 1,438 Santo Niño 1,120 Sisimon 925 MABINI (DOÑA ALICIA) 36,807 Cadunan 3,988 Pindasan 5,524 Cuambog (Pob.) 6,016 Tagnanan (Mampising) 4,735 Anitapan 3,435 Cabuyuan 1,940 Del Pilar 2,054 Libodon 1,145 Golden Valley (Maraut) 5,061 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population -

Municipality of Kiblawan Kiblawan, Davao Del Sur Mrs

MUNICIPALITY OF KIBLAWAN KIBLAWAN, DAVAO DEL SUR MRS. ERLINDA A. SILAGAN, MPDC Presenter Income Class 2nd Class Land Area 39,007 has. Number of Barangays 30 Population (CBMS 40,597 2010) Number of 10,180 Households Average Household 4 Size Location: Western portion of the Province of Davao del Sur Location: We are in Davao Province in Southern Mindanao The Municipality of Kiblawan manifested its intent to implement CBMS through Sangguniang Bayan Resolution No. 092 dated October 11, 2010. The implementation of the Community-Based Monitoring System project was made possible covering the 30 component barangays of the municipality through a Memorandum of Agreement entered into and executed on October 10, 2010 by and between: ◦ the Community Based Monitoring System (CBMS) Network Coordinating Team of the Angelo King Institute (AKI) for Economic and Business Studies of De La Salle University; ◦ the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) through the Bureau of Local Government Development (BLGD); ◦ the Department of Interior and Local Government, Regional Office XI, the Municipal Government Unit of Kiblawan, Davao del Sur; and ◦ the Sagittarius Mines, Incorporated (SMI). Lack or absence of data is a major concern, even a major constraint in local development planning and to the LGU in general. Absence of a data banking system is a time- consuming and resource-draining activity to have data inputs in different planning works. Gone are the days of “moon-gazing planners”. Gone is the song “You Can Do Magic” – theme song of a planner who lacks data. Good as having a vivid picture of local socio- economic situation. -

191118 Tulunan Earthquakes Snapshot

PHILIPPINES Tulunan, North Cotabato Earthquakes Snapshot As of 18 November 2019 A series of earthquakes struck in Tulunan, North Cotabato, between 16 and 31 October 2019. The earthquakes caused displacement, loss of lives and extensive damage to properties and infrastructure. Experts believe many of those affected will remain displaced for at least a year due to the cause and severity of the damage. The national government, which is leading the response, has setup a Central Coordination Center (CCC) to coordinate the response efforts and allocate resources among the affected local government units. The increase in the number of affected, particularly Tulunan, North Cotabato, is due to the ongoing assessment and validation conducted by the government. AFFECTED POPULATION POPULATION INSIDE/OUTSIDE ECs DAMAGED HOUSES DAMAGED INFRASTRUCTURES P. ROXAS P. ROXAS P. ROXAS P. ROXAS NORTH COTABATO ARAKAN NORTH COTABATO ARAKAN NORTH COTABATO ARAKAN NORTH COTABATO ARAKAN (REGION XII) (REGION XII) (REGION XII) ANTIPAS (REGION XII) ANTIPAS ANTIPAS MATALAM MATALAM MATALAM MATALAM KABACAN DAVAO DEL SUR KABACAN DAVAO DEL SUR KABACAN DAVAO DEL SUR KABACAN DAVAO DEL SUR MAGPET (REGION XI) MAGPET (REGION XI) (REGION XI) MAGPET (REGION XI) KIDAPAWAN CITY KIDAPAWAN CITY PAGAGAWAN KIDAPAWAN CITY KIDAPAWAN CITY MAKILALA MAKILALA MAKILALA MAKILALA MAGUINDANAO M’LANG ( MAGUINDANAO M’LANG ( MAGUINDANAO M’LANG ( MAGUINDANAO M’LANG ( STA. CRUZ STA. CRUZ STA. CRUZ (BARMM) (BARMM) (BARMM) (BARMM) BANSALAN BANSALAN BANSALAN BANSALAN TULUNAN TULUNAN TULUNAN TULUNAN ( DIGOS CITY ( DIGOS CITY ( DIGOS CITY ( DIGOS CITY ( MAGSAYSAY ( MAGSAYSAY ( MAGSAYSAY ( MAGSAYSAY HAGONOY HAGONOY HAGONOY HAGONOY COLUMBIO < 1,000 MATANAO < 1,000 MATANAO < 100 COLUMBIO MATANAO < 10 MATANAO SULTAN KUDARAT SULTAN KUDARAT SULTAN KUDARAT SULOP SULOP SULOP SULOP 1,000 - 5,000 1,000 - 5,000 (REGION XI) 100 - 500 (REGION XI) 10 - 20 SULTAN KUDARAT (REGION XI) MALALAG MALALAG MALALAG MALALAG KIBLAWAN KIBLAWAN KIBLAWAN (REGION XI) KIBLAWAN 5,000 - 10,000 5,000 - 10,000 500 - 1,000 20 - 50 SOUTH COTABATO STA.