Scope of Practice Determination for Health Care Professions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Ems Scope of Practice Model 2019

NATIONAL EMS SCOPE OF PRACTICE MODEL 2019 The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Education Credentialing Certification Licensure NHTSA III.NA110NAL -•w•• TRAPPIC u,n, ••-•nunoN DISCLAIMER This publication is distributed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation or the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. If trade or manufacturers’ names or products are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to the object of the publications and should not be construed as an endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Suggested APA Format Citation: National Association of State EMS Officials. National EMS Scope of Practice Model 2019 (Report No. DOT HS 812-666). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The National EMS Scope of Practice Model February 2019 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. DOT HS 812 666 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date National EMS Scope of Practice Model 2019 February 2019 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. National Association of State EMS Officials DOT-VNTSC-NHTSA-812-666 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) National Association of State EMS Officials 201 Park Washington Court 11. Contract or Grant No. Falls Church, VA 22046-4527 12. -

Iowa Emergency Medical Care Provider Scope of Practice

Iowa Department of Public Health Bureau of Emergency and Trauma Services Iowa Emergency Medical Care Provider Scope of Practice October 2019 “Protecting and Improving the Health of Iowans” LUCAS STATE OFFICE BUILDING 321 East 12th Street DES MOINES, IOWA 50319-0075 (515) 281-0620 (800) 728-3367 https://idph.iowa.gov/BETS/EMS Scope of Practice – Defined parameters of various duties or services that may be provided by an individual with specific credentials. Whether regulated by rule, statute, or court decision, it represents the limits of services an individual may legally perform. Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 Background ....................................................................................................................... 2 Overview of the EMS Profession ................................................................................... 2 The Evolution of the EMS Agenda for the Future .......................................................... 4 National EMS Educational Standards ............................................................................. 5 Interdependent Relationship Between Education, Certification, Licensure, and Credentialing ..................................................................................................................... 7 Medical Supervision.......................................................................................................... 8 Pilot Project ...................................................................................................................... -

JNR0120SE Globalprofile.Pdf

JOURNAL OF NURSING REGULATION VOLUME 10 · SPECIAL ISSUE · JANUARY 2020 THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF STATE BOARDS OF NURSING JOURNAL Volume 10 Volume OF • Special Issue Issue Special NURSING • January 2020 January REGULATION Advancing Nursing Excellence for Public Protection A Global Profile of Nursing Regulation, Education, and Practice National Council of State Boards of Nursing Pages 1–116 Pages JOURNAL OFNURSING REGULATION Official publication of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing Editor-in-Chief Editorial Advisory Board Maryann Alexander, PhD, RN, FAAN Mohammed Arsiwala, MD MT Meadows, DNP, RN, MS, MBA Chief Officer, Nursing Regulation President Director of Professional Practice, AONE National Council of State Boards of Nursing Michigan Urgent Care Executive Director, AONE Foundation Chicago, Illinois Livonia, Michigan Chicago, Illinois Chief Executive Officer Kathy Bettinardi-Angres, Paula R. Meyer, MSN, RN David C. Benton, RGN, PhD, FFNF, FRCN, APN-BC, MS, RN, CADC Executive Director FAAN Professional Assessment Coordinator, Washington State Department of Research Editors Positive Sobriety Institute Health Nursing Care Quality Allison Squires, PhD, RN, FAAN Adjunct Faculty, Rush University Assurance Commission Brendan Martin, PhD Department of Nursing Olympia, Washington Chicago, Illinois NCSBN Board of Directors Barbara Morvant, MN, RN President Shirley A. Brekken, MS, RN, FAAN Regulatory Policy Consultant Julia George, MSN, RN, FRE Executive Director Baton Rouge, Louisiana President-elect Minnesota Board of Nursing Jim Cleghorn, MA Minneapolis, Minnesota Ann L. O’Sullivan, PhD, CRNP, FAAN Treasurer Professor of Primary Care Nursing Adrian Guerrero, CPM Nancy J. Brent, MS, JD, RN Dr. Hildegarde Reynolds Endowed Term Area I Director Attorney At Law Professor of Primary Care Nursing Cynthia LaBonde, MN, RN Wilmette, Illinois University of Pennsylvania Area II Director Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Lori Scheidt, MBA-HCM Sean Clarke, RN, PhD, FAAN Area III Director Executive Vice Dean and Professor Pamela J. -

Emergency Medical Services Statutes and Regulations

Emergency Medical Services Statutes and Regulations Printed: August 2016 Effective: September 11, 2016 1 9/16/2016 Statutes and Regulations Table of Contents Title 63 of the Oklahoma Statutes Pages 3 - 13 Sections 1-2501 to 1-2515 Constitution of Oklahoma Pages 14 - 16 Article 10, Section 9 C Title 19 of the Oklahoma Statutes Pages 17 - 24 Sections 371 and 372 Sections 1- 1201 to 1-1221 Section 1-1710.1 Oklahoma Administrative Code Pages 25 - 125 Chapter 641- Emergency Medical Services Subchapter 1- General EMS programs Subchapter 3- Ground ambulance service Subchapter 5- Personnel licenses and certification Subchapter 7- Training programs Subchapter 9- Trauma referral centers Subchapter 11- Specialty care ambulance service Subchapter 13- Air ambulance service Subchapter 15- Emergency medical response agency Subchapter 17- Stretcher aid van services Appendix 1 Summary of rule changes Approved changes to the June 11, 2009 effective date to the September 11, 2016 effective date 2 9/16/2016 §63-1-2501. Short title. Sections 1-2502 through 1-2521 of this title shall be known and may be cited as the "Oklahoma Emergency Response Systems Development Act". Added by Laws 1990, c. 320, § 5, emerg. eff. May 30, 1990. Amended by Laws 1999, c. 156, § 1, eff. Nov. 1, 1999. NOTE: Editorially renumbered from § 1-2401 of this title to avoid a duplication in numbering. §63-1-2502. Legislative findings and declaration. The Legislature hereby finds and declares that: 1. There is a critical shortage of providers of emergency care for: a. the delivery of fast, efficient emergency medical care for the sick and injured at the scene of a medical emergency and during transport to a health care facility, and b. -

Credentialing and Defining the Scope of Clinical Practice

Directive # QH-HSD-034: 2014 Effective Date: 19 May 2020 Review Date: 8 October 2020 Supersedes: Version 2.0 Credentialing and defining the scope of clinical practice Purpose The purpose of this health service directive (HSD) is to ensure identified health professionals are credentialed and have a defined scope of clinical practice (SoCP) to support the delivery of safe and high quality health care within Hospital and Health Services (HHS). It also outlines specified clinical services, and the medical practitioners or dentists (employed or engaged) to that clinical service, that are identified as having a statewide/ multi HHS SoCP (refer to Schedule A). Scope This HSD applies to all HHSs and is relevant to professionals identified in the professional stream requirements section of this document. Health professionals employed within the Department of Health (the department) should refer to the appropriate policy, standard and guideline. Principles • patient safety — ensuring health professionals practice within the bounds of their education, training and competence and within the capacity and capability of the service in which they are working. • consistency — aligning with National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. • natural justice and procedural fairness — the credentialing and SoCP processes are underpinned by the principles of natural justice and procedural fairness. • due care and diligence — all parties act with due care and diligence to support procedural fairness. Credentialing and defining SoCP processes are underpinned by transparency and accountability. • equity — applicants be treated equally and without discrimination. All decisions shall be based on the professional competence of the applicant and the capacity of the relevant service. Effective From: XX May 2020 Page 1 of 17 Health Service Directive # QH-HSD-034:2014 Printed copies are uncontrolled Credentialing and defining the scope of clinical practice Outcomes All HHSs shall ensure all identified health professionals are credentialed and have a defined SoCP. -

2019 National EMS Scope of Practice Model

NATIONAL EMS SCOPE OF PRACTICE MODEL 2019 The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Education Credentialing Certification Licensure ��NHTSA III.NA110NAL -•w•• TRAPPIC u,n, ••-•nunoN DISCLAIMER This publication is distributed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation or the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. If trade or manufacturers’ names or products are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to the object of the publications and should not be construed as an endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Suggested APA Format Citation: National Association of State EMS Officials. National EMS Scope of Practice Model 2019 (Report No. DOT HS 812-666). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The National EMS Scope of Practice Model February 2019 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. DOT HS 812 666 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date National EMS Scope of Practice Model 2019 February 2019 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. National Association of State EMS Officials DOT-VNTSC-NHTSA-812-666 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) National Association of State EMS Officials 201 Park Washington Court 11. Contract or Grant No. Falls Church, VA 22046-4527 12. -

Expanding the Roles of Emergency Medical Services Providers: a Legal Analysis

Expanding the Roles of Emergency Medical Services Providers: A Legal Analysis This report was made possible through funding from the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR). The report was researched and prepared for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials by faculty at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. James G. Hodge, Jr., JD, LLM Lincoln Professor of Health Law and Ethics Director, Public Health Law and Policy Program Arizona State University Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law Daniel G. Orenstein, JD Adjunct Professor and Fellow, Public Health Law and Policy Program Arizona State University Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law Kim Weidenaar, JD Fellow, Public Health Law and Policy Program Arizona State University Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law Association of State and Territorial Health Officials 2231 Crystal Drive, Suite 450 Arlington, VA 22202 202-371-9090 tel | 202-371-9797 fax www.astho.org Table of Contents Table of Abbreviations. 3 Acknowledgements . 3 Disclaimer . 3 Executive Summary/Introduction. .4 Project Limits. .4 Project Organization. .5 Table 1: “Top Options, Practices, or Solutions” in Law or Policy Re: Expanded EMS. .6 I. Setting the Stage: Brief Primer on Expanded EMS Practices . .8 State and Local Programs . .8 Federal Support for Public-Private Collaborations . .9 Future of Community Paramedicine and Mobile Integrated Healthcare . 10 II. Ready, Set, Go: Legal Issues Underlying Expanded EMS Activity Triggers . .11 1 Figure 1: Triggers for EMS Activities . .11 Authorizing and Establishing Protocols . .12 Coordinating Limited Resources. .14 Provision and Payment. .14 Limitations on Selection Among Competing Providers. -

Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, Second Edition Guides Nurses in the Application of Their Professional Skills and Responsibilities

2010 EDITION Scope AND Standards OF PRACTICE Nursing 2nd Edition ANA Standards of Professional Nursing Practice The Standards of Practice Standards of Practice describe a competent level of nursing care Standard 1. Assessment as demonstrated by The registered nurse collects comprehensive data pertinent to the critical thinking the healthcare consumer’s health or the situation. model known as the nursing process. The Standard 2. Diagnosis nursing process includes The registered nurse analyzes the assessment data to determine the components of the diagnoses or issues. assessment, diagnosis, outcomes identification, Standard 3. Outcomes Identification planning, implementation, The registered nurse identifies expected outcomes for a plan and evaluation. individualized to the healthcare consumer or the situation. Accordingly, the nursing process encompasses Standard 4. Planning significant actions The registered nurse develops a plan that prescribes strategies taken by registered and alternatives to attain expected outcomes. nurses and forms the foundation of the nurse’s Standard 5. Implementation decision-making. The registered nurse implements the identified plan. Standard 5A. Coordination of Care The registered nurse coordinates care delivery. Standard 5B. Health Teaching and Health Promotion The registered nurse employs strategies to promote health and a safe practice environment. Standard 5C. Consultation The graduate-level prepared specialty nurse or advanced practice registered nurse provides consultation to influence the identified plan, enhance the abilities of others, and effect change. Standard 5D. Prescriptive Authority and Treatment The advanced practice registered nurse uses prescriptive authority, procedures, referrals, treatments, and therapies in accordance with state and federal laws and regulations. Standard 6. Evaluation The registered nurse evaluates progress toward attainment of outcomes. -

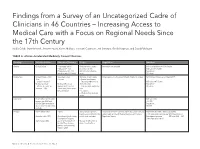

Findings from a Survey of an Uncategorized Cadre of Clinicians

Findings from a Survey of an Uncategorized Cadre of Clinicians in 46 Countries – Increasing Access to Medical Care with a Focus on Regional Needs Since the 17th Century Nadia Cobb, Marie Meckel, Jennifer Nyoni, Karen Mulitalo, Hoonani Cuadrado, Jeri Sumitani, Gerald Kayingo, and David Fahringer TABLE A. African Accelerated Medically Trained Clinicians Country Title Established Education/Training Scope Regulation Numbers Angola Clinical Officer – secondary school Medicine minor surgery Information not available Info not available on # CO in Angola – Education– 3 yrs. obstetrics (no CS) MD ratio .011/10,000 (Emigration of Drs 71% Work in rural and urban Population: based on early 2000 data) areas 19 million Burkina Faso Clinical Officer – 1942 Secondary school Medicine, minor surgery Organization – the Association Health Attaché in surgery 1241 Clinical Officers as of March 2015 Also : – 3 years – General practitioners – attaché’s desanté’ – Emergency obstetrics at MD ratio .0047/10,000 Medical assistant Medical officers can district hospital Population: – Attaché de santé’ en upgrade to CO’s with 6 – Can deal with obstructive 18 million chirurgie – 1965 month curriculum in emer- labor gency medicine – C sections – Work in urban and rural areas Cabo Verde Health Officer per literature MD ratio 2010 review– per WHO and .3/1,000 MOH in Cabo Verde these Population: do not exist – no other info 538,535 available Ethiopia Health Officer 1954 4 years 95% practice in primary Directorate of Health Facilities and Professionals Licensing Health Officers 2008 > 900 had graduated Health care unit (District HC) under Health and Health Related Services and Products 3,168 were under training– per WHO Health Sector discontinued in 1974 According to Health Sector both in rural and urban Regulation Agency Development program MD ratio 2009 .025 Development Program: /1000 Population: 96 mil started again 2004 accelerated program of Manage health center & Health Officer training district health offices (generic and upgrading) began in 2005. -

Reforming Scope of Practice

REFORMING SCOPES OF PRACTICE A WHITE PAPER by Rebecca LeBuhn Board Chair Citizen Advocacy Center and David A. Swankin, Esq. President and CEO Citizen Advocacy Center July 2010 CITIZEN ADVOCACY CENTER 1400 SIXTEENTH STREET NW • SUITE #101 • WASHINGTON, DC 20036 TELEPHONE (202) 462-1174 • FAX (202) 354-5372 WWW.CACENTER.ORG • [email protected] REFORMING SCOPES OF PRACTICE A WHITE PAPER Abstract ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Reforming Scope of Practice ....................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 The Challenges ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Most States Are Approaching Healthcare Reform and Scope of Practice in a Piecemeal Fashion ........ 5 Case Study: Pennsylvania ....................................................................................................................... 6 How Did This Happen in Pennsylvania? .................................................................................................. 8 The Evidence Base for Expanded Scopes ................................................................................................ 9 Developing Evidence in the -

ANA Scope and Standards of Nursing Practice

Scope and Standards Nursing of Practice 3rd Edition American Nurses Association Pre-publication copy June and July 2013: Restricted use for designatedSilver reviewers Spring, Marylandonly. 2015 The American Nurses Association (ANA) is a national professional association. This ANA publication, Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, Third Edition, reflects the thinking of the nursing profession on various issues and should be reviewed in conjunction with state board of nursing policies and practices. State law, rules, and regulations govern the practice of nursing, while Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, Third Edition, guides nurses in the application of their professional knowledge, skills, and responsibilities. American Nurses Association 8515 Georgia Avenue, Suite 400 Silver Spring, MD 20910-3492 1-800-274-4ANA http://www.Nursingworld.org Published by Nursesbooks.org The Publishing Program of ANA http://www.Nursesbooks.org Copyright ©2015 American Nurses Association. All rights reserved. Reproduction or transmission in any form is not permitted without written permission of the American Nurses Association (ANA). This publication may not be translated without written permission of ANA. For inquiries, or to report unauthorized use, email copyright@ ana.org. Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file with the Library of Congress ISBN-13: 978-1-55810-619-2 SAN: 851-3481 07/2015 First printing: July 2015 Pre-publication copy June and July 2013: Restricted use for designated reviewers only. Contents Contributors vii Overview of the -

Scope of Practice of Health Professionals in the State of Michigan

SCOPE OF PRACTICE OF HEALTH PROFESSIONALS IN THE STATE OF MICHIGAN Prepared by Public Sector Consultants Project Manager Researcher/Writer Peter Pratt Lisa Katz Michigan State Medical Society Michigan Osteopathic Association ii SCOPE OF PRACTICE OF HEALTH PROFESSIONALS IN THE STATE OF MICHIGAN Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................1 THE REGULATORY SYSTEM ........................................................... 3 DEFINING HEALTH PROFESSIONS ...............................................5 Allopathic Medicine and Osteopathic Medicine and Surgery ..........................................5 Physician Assistance................................................................7 Nursing ..................................................................................7 Psychology ..............................................................................9 Chiropractic ............................................................................9 Optometry............................................................................10 SCOPE OF PRACTICE AND LIMITATIONS ...................................13 Physicians .............................................................................13 Physician Assistants ..............................................................16 Nurses ..................................................................................20 Psychologists, Chiropractors, and Optometrists .....................24 DELEGATION AND SUPERVISION ...............................................33