Baglama) According То Reagions in Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranian Traditional Music Dastgah Classification

12th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR 2011) IRANIAN TRADITIONAL MUSIC DASTGAH CLASSIFICATION SajjadAbdoli Computer Department, Islamic Azad University, Central Tehran Branch, Tehran, Iran [email protected] ABSTRACT logic to integrate music tuning theory and practice. After feature extraction, the proposed system assumes In this study, a system for Iranian traditional music Dastgah each performed note as an IT2FS, so each musical piece is a classification is presented. Persian music is based upon a set set of IT2FSs.The maximum similarity between this set and of seven major Dastgahs. The Dastgah in Persian music is theoretical Dastgah prototypes, which are also sets of similar to western musical scales and also Maqams in IT2FSs, indicates the desirable Dastgah. Gedik et al. [10] Turkish and Arabic music. Fuzzy logic type 2 as the basic used the songs of the dataset to construct the patterns, part of our system has been used for modeling the whereas in this study, the system makes no assumption about uncertainty of tuning the scale steps of each Dastgah. The the data except that different Dastgahs have different pitch method assumes each performed note as a Fuzzy Set (FS), so intervals. Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of the each musical piece is a set of FSs. The maximum similarity system. We also show that the system can recognize the between this set and theoretical data indicates the desirable Dastgah of the songs of the proposed dataset with overall Dastgah. In this study, a collection of small-sized dataset for accuracy of 85%. Persian music is also given. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

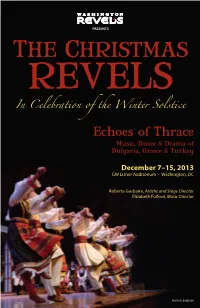

Read This Year's Christmas Revels Program Notes

PRESENTS THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey December 7–15, 2013 GW Lisner Auditorium • Washington, DC Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director PHOTO BY ROGER IDE THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey The Washington Featuring Revels Company Karpouzi Trio Koleda Chorus Lyuti Chushki Koros Teens Spyros Koliavasilis Survakari Children Tanya Dosseva & Lyuben Dossev Thracian Bells Tzvety Dosseva Weiner Grum Drums Bryndyn Weiner Kukeri Mummers and Christmas Kamila Morgan Duncan, as The Poet With And Folk-Dance Ensembles The Balkan Brass Byzantio (Greek) and Zharava (Bulgarian) Emerson Hawley, tuba Radouane Halihal, percussion Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director Gregory C. Magee, Production Manager Dedication On September 1, 2013, Washington Revels lost our beloved Reveler and friend, Kathleen Marie McGhee—known to everyone in Revels as Kate—to metastatic breast cancer. Office manager/costume designer/costume shop manager/desktop publisher: as just this partial list of her roles with Revels suggests, Kate was a woman of many talents. The most visibly evident to the Revels community were her tremendous costume skills: in addition to serving as Associate Costume Designer for nine Christmas Revels productions (including this one), Kate was the sole costume designer for four of our five performing ensembles, including nineteenth- century sailors and canal folk, enslaved and free African Americans during Civil War times, merchants, society ladies, and even Abraham Lincoln. Kate’s greatest talent not on regular display at Revels related to music. -

A Musical Instrument of Global Sounding Saadat Abdullayeva Doctor of Arts, Professor

Focusing on Azerbaijan A musical instrument of global sounding Saadat ABDULLAYEVA Doctor of Arts, Professor THE TAR IS PRObabLY THE MOST POPULAR MUSICAL INSTRUMENT AMONG “The trio”, 2005, Zakir Ahmadov, AZERbaIJANIS. ITS SHAPE, WHICH IS DIFFERENT FROM OTHER STRINGED INSTRU- bronze, 40x25x15 cm MENTS, IMMEDIATELY ATTRACTS ATTENTION. The juicy and colorful sounds to the lineup of mughams, and of a coming from the strings of the tar bass string that is used only for per- please the ear and captivate people. forming them. The wide range, lively It is certainly explained by the perfec- sounds, melodiousness, special reg- tion of the construction, specifically isters, the possibility of performing the presence of twisted steel and polyphonic chords, virtuoso passag- copper strings that convey all nuanc- es, lengthy dynamic sound rises and es of popular tunes and especially, attenuations, colorful decorations mughams. This is graphically proved and gradations of shades all allow by the presence on the instrument’s the tar to be used as a solo, accom- neck of five frets that correspondent panying, ensemble and orchestra 46 www.irs-az.com instrument. But nonetheless, the tar sounding board instead of a leather is a recognized instrument of solo sounding board contradict this con- mughams when the performer’s clusion. The double body and the mastery and the technical capa- leather sounding board are typical of bilities of the instrument manifest the geychek which, unlike the tar, has themselves in full. The tar conveys a short neck and a head folded back- the feelings, mood and dreams of a wards. Moreover, a bow is used play person especially vividly and fully dis- this instrument. -

Tarih Boyunca Türk Askeri Müziğinde Kullanilan Sazlar

i T.C. SELÇUK ÜNøVERSøTESø SOSYAL Bø/øMLERø ENSTøTÜSÜ MÜZøK ANABø/øM DALI TÜRK SANAT MÜZøöø Bø/øM DALI TARøH BOYUNCA TÜRK ASKERø MÜZøöøNDE KULLANILAN SAZLAR Süleyman YARDIM YÜKSEK LøSANS TEZø DanÕúman Yrd. Doç. Dr. Sema SEVøNÇ Konya – 2010 ii T.C. SELÇUK ÜNøVERSøTESø Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlü÷ü %ø/øMSEL ETøK SAYFASI Bu tezin proje safhasÕndan sonuçlanmasÕna kadarki bütün süreçlerde bilimsel eti÷e ve akademik kurallara özenle riayet edildi÷ini, tez içindeki bütün bilgilerin etik davranÕú ve akademik kurallar çerçevesinde elde edilerek sunuldu÷unu, ayrÕca tez yazÕm kurallarÕna uygun olarak hazÕrlanan bu çalÕúmada baúkalarÕQÕn eserlerinden yararlanÕlmasÕ durumunda bilimsel kurallara uygun olarak atÕf yapÕldÕ÷ÕQÕ bildiririm. Süleyman YARDIM iii T.C. SELÇUK ÜNøVERSøTESø Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlü÷ü YÜKSEK LøSANS TEZø KABUL FORMU Süleyman YARDIM tarafÕndan hazÕrlanan Tarih Boyunca Türk Askeri Müzi÷inde KullanÕlan Sazlar baúOÕklÕ bu çalÕúma, tarihinde yapÕlan savunma sÕnavÕ sonucunda oybirli÷i/oyçoklu÷u ile baúarÕOÕ bulunarak, jürimiz tarafÕndan yüksek lisans tezi olarak kabul edilmiútir. DanÕúman Yrd. Doç. Dr. Sema SEVøNÇ jüri jüri Prof. Yusuf AKBULUT Yrd. Doç. Dr. Serdar ÇAKIRER iv TEùEKKÜR Yüksek lisans e÷itimim boyunca desteklerini hiç esirgemeyen tez danÕúman hocam Yrd. Doç. Dr. Sema SEVøÇ’ e, bu tezin baúlangÕFÕndan bugüne kadar gelemsinde sonsuz deste÷i bulunan sevgili hocam Prof. Yusuf AKBULUT’ a, ilk tez danÕúmanÕm ve konu seçiminde bana yardÕmcÕ olan hocam Yrd. Doç. Hamit ÖNAL’A, tezi hazÕrlamamda büyük yardÕmlarÕQÕ gördü÷üm Kültür ve Turizm BakanlÕ÷Õ Klasik Türk Müzi÷i ses sanatçÕVÕ Timuçin ÇEVøKOöLU beyefendi’ye ve bu tezin son haline gelmesinde bana yardÕmlarÕQÕ hiç esirgemeyen arkadaúÕm Arú. Gör. Murat CAN’ a sonsuz teúekkürlerimi sunarÕm. -

Music of Central Asia and of the Volga-Ural Peoples. Teaching Aids for the Study of Inner Asia No

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 295 874 SO 019 077 AUTHOR Slobin, Mark TITLE Music of Central Asia and of the Volga-Ural Peoples. Teaching Aids for the Study of Inner Asia No. 5. INSTITUTION Indiana Univ., Bloomington. Asian Studies Research Inst. SPONS AGENCY Association for Asian Studies, .an Arbor, Mich. PUB DATE 77 NOTE 68p. AVAILABLE FROMAsian Studies Research Institute, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405 ($3.00). PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Education; Culture; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; Higher Education; Instructional Materials; *Music; Musical Instruments; Music Education; *Non Western Civilization; Resource Materials; Resource Units; Secondary Education; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Asia (Central).; *Asia (Volga Ural Region); Folk Music; USSR ABSTRACT The music of the peoples who inhabit either Central Asia or the Volga-Ural region of Asia is explored in this document, which provides information that can be incorporated into secondary or higher education courses. The Central Asian music cultures of the Kirghiz, Kazakhs, Turkmens, Karakalpaks, Uighurs, Tajiks, and Uzbeks are described and compared through examinations of: (1) physical environmental factors; (2) cultural patterns; (3) history; (4) music development; and (5) musical instruments. The music of the Volga-Ural peoples, who comprise the USSR nationalities of the Mari (Cheremis), Chuvash, Udmurts (Votyaks), Mordvins, Bashkirs, Tatars, and Kalmucks, is examined, with an emphasis on differences in musical instruments. A 13-item bibliography of Central Asian music and a 17-item Volga-Ural music bibliography are included. An appendix contains examples of musical scores from these regions. -

SOUNDSCAPES: the Arab World Vocabulary

SOUNDSCAPES: The Arab World Vocabulary ADHAN The Islamic call to prayer. MAFRAJ A window‐lined room at the AL‐ANDALUS Around 1000 CE, the area now top of a house. called Spain and part of North MAGHREB The North African dessert. Africa. MAQAM Scales and notes that define AL‐QAHIRAH The Arabic name for Cairo, Arabic music tonality. Egypt. MINARET Part of a MOSQUE, a tower ARDHA A traditional Arabic dance, used for communication. common in Saudi Arabia. MIZHWIZ A double‐pipe double‐reed AS‐SANTOOR A multi‐stringed instrument wind instrument. played with wooden sticks. MIZMAR A single‐pipe double‐reed wind BEDOUIN Nomadic people of the Arabian instrument. and North African desert. MOSQUE An Islamic place of worship. BENDIR A round, flat, wooden‐framed NAY An end‐blown wind instrument. drum. OSTINATO Italian musical term for a BERBER Indigenous people of the North repeating pattern. African desert OUD/AL‐‘UD A pear‐shaped string CHA’ABI/SHA’ABI A style of dance and music instrument, similar to a lute. popular in some poorer Arab QANUN A large, flat multi‐stringed communities. instrument. DABKE A traditional line dance, RABABEH A single‐stringed bowed fiddle. popular in Lebanon. REBEC The European version of the DALOONAH Improvised music often used REBABEH, precursor to the with DABKE. violin. DERVISH Devout SUFI Muslims, similar to RIQ/TAR A round, flat, wooden‐framed Christian monks. drum with jingling plates DJELLABA A tunic, often worn by BERBER around the rim, similar to a men. tambourine. DJEMBE A West African drum, similar to SAWT A bluesy style of Arabic music, a DUMBEK. -

1 Understanding Different Interactions of Coffee, Tobacco and Opium Culture in the Lands of Ottoman Empire in the Light of the P

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Istanbul Bilgi University Library Open Access UNDERSTANDING DIFFERENT INTERACTIONS OF COFFEE, TOBACCO AND OPIUM CULTURE IN THE LANDS OF OTTOMAN EMPIRE IN THE LIGHT OF THE PIPES OBTAINED IN EXCAVATIONS ERTUĞRUL SÜNGÜ İSTANBUL BİLGİ UNIVERSITY 2014 1 UNDERSTANDING DIFFERENT INTERACTIONS OF COFFEE, TOBACCO AND OPIUM CULTURE IN THE LANDS OF OTTOMAN EMPIRE IN THE LIGHT OF THE PIPES OBTAINED IN EXCAVATIONS Thesis submitted to the Institute for Social Sciences In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Ertuğrul Süngü İSTANBUL BİLGİ UNIVERSITY 2014 2 3 An abstract of the thesis submitted by Ertuğrul Süngü, for the degree of Master of Arts in History from the Institute of Social Sciences to be taken in September 2014 Title: Understanding Different Interactions of Coffee, Tobacco and Opium Culture in the Lands of Ottoman Empire in the Light of the Pipes Obtained in Excavations This M.A. thesis mainly focuses on tobacco introduced to the Ottoman Empire in the 17th century and along with tobacco, it questions how pipe making shaped the everyday life in the Empire both socially and culturally. This inventory, better known as Tophane pipe making, came out in a large part of the Ottoman Empire in different ways according to its period, region and production style. In a short span of time, tobacco spread to a large part of the empire, was first consumed as a remedy and soon after as a stimulating substance. The variety in the usage of opium, the consumption of wine despite its being banned, and especially the excessive consumption of coffee by almost everyone paved the way for tobacco. -

History of Guitar

History of Guitar A Brief History of the Guitar by Paul Guy The guitar is an ancient and noble instrument, whose history can be traced back over 4000 years. Many theories have been advanced about the instrument's ancestry. It has often been claimed that the guitar is a development of the lute, or even of the ancient Greek kithara. Research done by Dr. Michael Kasha in the 1960's showed these claims to be without merit. He showed that the lute is a result of a separate line of development, sharing common ancestors with the guitar, but having had no influence on its evolution. The influence in the opposite direction is undeniable, however - the guitar's immediate forefathers were a major influence on the development of the fretted lute from the fretless oud which the Moors brought with them to to Spain. The sole "evidence" for the kithara theory is the similarity between the greek word "kithara" and the Spanish word "quitarra". It is hard to imagine how the guitar could have evolved from the kithara, which was a completely different type of instrument - namely a square-framed lap harp, or "lyre". It would also be passing strange if a square-framed seven-string lap harp had given its name to the early Spanish 4-string "quitarra". Dr. Kasha turns the question around and asks where the Greeks got the name "kithara", and points out that the earliest Greek kitharas had only 4 strings when they were introduced from abroad. He surmises that the Greeks hellenified the old Persian name for a 4- stringed instrument, "chartar". -

Joël Bons E C | P Music1 Air#3In C Contextair#4 Air#0 Air#1 Air#2 Joël Bons

Joël Bons E C | P Music1 air#3in C contextair#4 air#0 air#1 air#2 Joël Bons Invitation / 3 The international music world is increasingly shaped by music from diverse cultures. However, almost no structural research has been performed into the impact this has, or might have in the future, on musicians in training. air#3 That the distinction between composition and performance differs according to culture is also an area of interest. The Amsterdam Conservatory has invited Joël Bons to investi- gate the opportunities arising from the combination of differ- ent music cultures, for both composition and performance prac- tice. Particular attention will be given to bringing these two practices closer to one another. Where possible he will, in response to his findings, advise the Board on the selection of guest tutors and other teaching air#4 staff, the development and reform of the curriculum, and the programming of the Composition Department. In addition, the Amsterdam Conservatory has asked Joël Bons to investigate the feasibility of a Centre of Excellence at the Conservatory devoted to various aspects of non-Western music, namely knowledge, research, composition and performance. air#0 air#1 From the letter of appointment air#2 Joël Bons Joël Bons studied guitar and composition at the Sweelinck Conservatory in 4 5 Amsterdam. After completion of his composition studies, he attended summer Winds courses by Franco Donatoni in Siena and the Darmstädter Ferienkurse für Neue Musik. In 1982 he resumed his composition studies, with Brian Ferneyhough in Freiburg. and Strings At the beginning of the 1980s, Joël Bons co-founded the Nieuw Ensemble, a leading 3 international ensemble for contemporary music that is pioneering in its programming (02–2005) / and innovative in its repertoire. -

Classification of Indian Musical Instruments with the General

Classification of Indian Musical Instruments With the general background and perspective of the entire field of Indian Instrumental Music as explained in previous chapters, this study will now proceed towards a brief description of Indian Musical Instruments. Musical Instruments of all kinds and categories were invented by the exponents of the different times and places, but for the technical purposes a systematic-classification of these instruments was deemed necessary from the ancient time. The classification prevalent those days was formulated in India at least two thousands years ago. The first reference is in the Natyashastra of Bharata. He classified them as ‘Ghana Vadya’, ‘Avanaddha Vadya’, ‘Sushira Vadya’ and ‘Tata Vadya’.1 Bharata used word ‘Atodhya Vadya’ for musical instruments. The term Atodhya is explained earlier than in Amarkosa and Bharata might have adopted it. References: Some references with respect to classification of Indian Musical Instruments are listed below: 1. Bharata refers Musical Instrument as ‘Atodhya Vadya’. Vishnudharmotta Purana describes Atodhya (Ch. XIX) of four types – Tata, Avnaddha, Ghana and Sushira. Later, the term ‘Vitata’ began to be used by some writers in place of Avnaddha. 2. According to Sangita Damodara, Tata Vadyas are favorite of the God, Sushira Vadyas favourite of the Gandharvas, whereas Avnaddha Vadyas of the Rakshasas, while Ghana Vadyas are played by Kinnars. 3. Bharata, Sarangdeva (Ch. VI) and others have classified the musical instruments under four heads: 1 Fundamentals of Indian Music, Dr. Swatantra Sharma , p-86 53 i. Tata (String Instruments) ii. Avanaddha (Instruments covered with membrane) iii. Sushira (Wind Instruments) iv. Ghana (Solid, or the Musical Instruments which are stuck against one another, such as Cymbals). -

NOSTALGIA, EMOTIONALITY, and ETHNO-REGIONALISM in PONTIC PARAKATHI SINGING by IOANNIS TSEKOURAS DISSERTATION Submitted in Parti

NOSTALGIA, EMOTIONALITY, AND ETHNO-REGIONALISM IN PONTIC PARAKATHI SINGING BY IOANNIS TSEKOURAS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Donna A. Buchanan, Chair Professor Emeritus Thomas Turino Professor Gabriel Solis Professor Maria Todorova ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the multilayered connections between music, emotionality, social and cultural belonging, collective memory, and identity discourse. The ethnographic case study for the examination of all these relations and aspects is the Pontic muhabeti or parakathi. Parakathi refers to a practice of socialization and music making that is designated insider Pontic Greek. It concerns primarily Pontic Greeks or Pontians, the descendants of the 1922 refugees from Black Sea Turkey (Gr. Pontos), and their identity discourse of ethno-regionalism. Parakathi references nightlong sessions of friendly socialization, social drinking, and dialogical participatory singing that take place informally in coffee houses, taverns, and households. Parakathi performances are reputed for their strong Pontic aesthetics, traditional character, rich and aesthetically refined repertoire, and intense emotionality. Singing in parakathi performances emerges spontaneously from verbal socialization and emotional saturation. Singing is described as a confessional expression of deeply personal feelings