Duev, R., Gusla

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

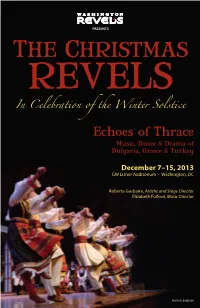

Read This Year's Christmas Revels Program Notes

PRESENTS THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey December 7–15, 2013 GW Lisner Auditorium • Washington, DC Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director PHOTO BY ROGER IDE THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey The Washington Featuring Revels Company Karpouzi Trio Koleda Chorus Lyuti Chushki Koros Teens Spyros Koliavasilis Survakari Children Tanya Dosseva & Lyuben Dossev Thracian Bells Tzvety Dosseva Weiner Grum Drums Bryndyn Weiner Kukeri Mummers and Christmas Kamila Morgan Duncan, as The Poet With And Folk-Dance Ensembles The Balkan Brass Byzantio (Greek) and Zharava (Bulgarian) Emerson Hawley, tuba Radouane Halihal, percussion Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director Gregory C. Magee, Production Manager Dedication On September 1, 2013, Washington Revels lost our beloved Reveler and friend, Kathleen Marie McGhee—known to everyone in Revels as Kate—to metastatic breast cancer. Office manager/costume designer/costume shop manager/desktop publisher: as just this partial list of her roles with Revels suggests, Kate was a woman of many talents. The most visibly evident to the Revels community were her tremendous costume skills: in addition to serving as Associate Costume Designer for nine Christmas Revels productions (including this one), Kate was the sole costume designer for four of our five performing ensembles, including nineteenth- century sailors and canal folk, enslaved and free African Americans during Civil War times, merchants, society ladies, and even Abraham Lincoln. Kate’s greatest talent not on regular display at Revels related to music. -

Chapter IX: Ukrainian Musical Folklore Discography As a Preserving Factor

Art Spiritual Dimensions of Ukrainian Diaspora: Collective Scientific Monograph DOI 10.36074/art-sdoud.2020.chapter-9 Nataliia Fedorniak UKRAINIAN MUSICAL FOLKLORE DISCOGRAPHY AS A PRESERVING FACTOR IN UKRAINIAN DIASPORA NATIONAL SPIRITUAL EXPERIENCE ABSTRACT: The presented material studies one of the important forms of transmission of the musical folklore tradition of Ukrainians in the United States and Canada during the XX – the beginning of the XXI centuries – sound recording, which is a component of the national spiritual experience of emigrants. Founded in the 1920s, the recording industry has been actively developed and has become a form of preservation and promotion of the traditional musical culture of Ukrainians in North America. Sound recordings created an opportunity to determine the features of its main genres, the evolution of forms, that are typical for each historical period of Ukrainians’ sedimentation on the American continent, as well as to understand the specifics of the repertoire, instruments and styles of performance. Leading record companies in the United States have recorded authentic Ukrainian folklore reconstructed on their territory by rural musicians and choirs. Arranged folklore material is represented by choral and bandura recordings, to which are added a large number of records, cassettes, CDs of vocal-instrumental pop groups and soloists, where significantly and stylistically diversely recorded secondary Ukrainian folklore (folklorism). INTRODUCTION. The social and political situation in Ukraine (starting from the XIX century) caused four emigration waves of Ukrainians and led to the emergence of a new cultural phenomenon – the art and folklore of Ukrainian emigration, i.e. diaspora culture. Having found themselves in difficult ambiguous conditions, where there was no favorable living environment, Ukrainian musical folklore began to lose its original identity and underwent assimilation processes. -

7'Tie;T;E ~;&H ~ T,#T1tmftllsieotog

7'tie;T;e ~;&H ~ t,#t1tMftllSieotOg, UCLA VOLUME 3 1986 EDITORIAL BOARD Mark E. Forry Anne Rasmussen Daniel Atesh Sonneborn Jane Sugarman Elizabeth Tolbert The Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology is an annual publication of the UCLA Ethnomusicology Students Association and is funded in part by the UCLA Graduate Student Association. Single issues are available for $6.00 (individuals) or $8.00 (institutions). Please address correspondence to: Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology Department of Music Schoenberg Hall University of California Los Angeles, CA 90024 USA Standing orders and agencies receive a 20% discount. Subscribers residing outside the U.S.A., Canada, and Mexico, please add $2.00 per order. Orders are payable in US dollars. Copyright © 1986 by the Regents of the University of California VOLUME 3 1986 CONTENTS Articles Ethnomusicologists Vis-a-Vis the Fallacies of Contemporary Musical Life ........................................ Stephen Blum 1 Responses to Blum................. ....................................... 20 The Construction, Technique, and Image of the Central Javanese Rebab in Relation to its Role in the Gamelan ... ................... Colin Quigley 42 Research Models in Ethnomusicology Applied to the RadifPhenomenon in Iranian Classical Music........................ Hafez Modir 63 New Theory for Traditional Music in Banyumas, West Central Java ......... R. Anderson Sutton 79 An Ethnomusicological Index to The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Part Two ............ Kenneth Culley 102 Review Irene V. Jackson. More Than Drumming: Essays on African and Afro-Latin American Music and Musicians ....................... Norman Weinstein 126 Briefly Noted Echology ..................................................................... 129 Contributors to this Issue From the Editors The third issue of the Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology continues the tradition of representing the diversity inherent in our field. -

Viktória Herencsár: Sound of Eurasia

Viktória Herencsár: Sound of Eurasia There was organize a festival for the instrument family of zither and cimbalom in the capital of Buryatia, Ulan Ude from 13. to 18. September 2011. I was invited to this event to show the culture of the Hungarian cimbalom. The place of the festival was in the Academy of Arts in Ulan Ude. The lectures were in the class rooms and the concerts were in the concert hall of the Academy with 800 seats. The event began on 13th September with the meeting between the participants and the leaders of the organizing committee (cultural minister of the state, mayor of the town Ulan Ude, president of the Academy, etc.) The local artists gave concert on the opening ceremony, who played on their national instruments, yataga and yochin. The yataga is same instrument like the Chinese guchen or Japan koto. The yochin is same, like the Chinese yangqin. Citizens of the Buryatia consist of Buryatian, Chinese, Mongolian and Russian people. Their music is consisting of the music culture of these nations. We can hear music, which character is like the Chinese music (pentatonic, many inflections), melodies with effect of the Mongolian throat singing, Russian style melodies, etc. After the national program of the opening ceremony had concert of Wilfried Scharf from Austria, who played on the Stayer zither. He played Austrian folk melodies and classical music. The next day had the lecturer of the Russian, Estonian and Chinese professors about the gusli, kannel and guchen. In line with this program were the lecturer about the cimbalom and yangqin. -

TITLE Pages 160518

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/64500 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Young, R.C. Title: La Cetra Cornuta : the horned lyre of the Christian World Issue Date: 2018-06-13 La Cetra Cornuta : the Horned Lyre of the Christian World Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof.mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op 13 juni 2018 klokke 15.00 uur door Robert Crawford Young Born in New York (USA) in 1952 Promotores Prof. dr. h.c. Ton Koopman Universiteit Leiden Prof. Frans de Ruiter Universiteit Leiden Prof. dr. Dinko Fabris Universita Basilicata, Potenza; Conservatorio di Musica ‘San Pietro a Majella’ di Napoli Promotiecommissie Prof.dr. Henk Borgdorff Universiteit Leiden Dr. Camilla Cavicchi Centre d’études supérieures de la Renaissance Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Université de Tours Prof.dr. Victor Coelho School of Music, Boston University Dr. Paul van Heck Universiteit Leiden Prof.dr. Martin Kirnbauer Universität Basel en Schola Cantorum Basiliensis Dr. Jed Wentz Universiteit Leiden Disclaimer: The author has made every effort to trace the copyright and owners of the illustrations reproduced in this dissertation. Please contact the author if anyone has rights which have not been acknowledged. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Foreword ix Glossary xi Introduction xix (DE INVENTIONE / Heritage, Idea and Form) 1 1. Inventing a Christian Cithara 2 1.1 Defining -

Mariinsky at BAM Opens with a Contemporary Opera Rarity—The Enchanted Wanderer, Jan 14

Mariinsky at BAM opens with a contemporary opera rarity—The Enchanted Wanderer, Jan 14 Rodion Shchedrin’s mystic opera comes to New York in its first full staging Bloomberg Philanthropies is the 2014—2015 Season Sponsor BAM and the Mariinsky present The Enchanted Wanderer By Rodion Shchedrin Directed by Alexei Stepanyuk Mariinsky Opera Musical direction by Valery Gergiev Conducted by Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer after the novel by Nikolai Leskov, The Enchanted Wanderer Set design by Alexander Orlov Costume design by Irina Cherednikova Lighting design by Yevgeny Ganzburg Choreography by Dmitry Korneyev Cast: Oleg Sychov (Ivan Severyanovich Flyagin, Storyteller) Andrei Popov (Flogged monk, Prince, Magnetiser, Old man in the woods, Storyteller) Kristina Kapustinskaya (Grusha the Gypsy, Storyteller) In Russian with English titles BAM Howard Gilman Opera House (30 Lafayette Ave) Jan 14 at 7:30pm Tickets start at $45 Brooklyn, Dec 8, 2014—Rodion Shchedrin’s The Enchanted Wanderer—in a fully staged US production premiere—ushers in the momentous, two-week BAM residency of the Mariinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg, led by Artistic Director Valery Gergiev, with its world- renowned opera, ballet, and orchestra on one stage in Brooklyn. The opera, a commission of the New York Philharmonic, has not been performed in New York since its world premiere in 2002. In The Enchanted Wanderer, Ivan Severyanovich Flyagin, the eponymous wanderer and a repentant monk, recounts his youthful misadventures and entanglement in the torrid love affair of the Prince and the beautiful Gypsy girl Grusha. Rodion Shchedrin wrote the libretto based on a novel by Nikolai Leskov (whose story was also the source of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk). -

NOSTALGIA, EMOTIONALITY, and ETHNO-REGIONALISM in PONTIC PARAKATHI SINGING by IOANNIS TSEKOURAS DISSERTATION Submitted in Parti

NOSTALGIA, EMOTIONALITY, AND ETHNO-REGIONALISM IN PONTIC PARAKATHI SINGING BY IOANNIS TSEKOURAS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Donna A. Buchanan, Chair Professor Emeritus Thomas Turino Professor Gabriel Solis Professor Maria Todorova ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the multilayered connections between music, emotionality, social and cultural belonging, collective memory, and identity discourse. The ethnographic case study for the examination of all these relations and aspects is the Pontic muhabeti or parakathi. Parakathi refers to a practice of socialization and music making that is designated insider Pontic Greek. It concerns primarily Pontic Greeks or Pontians, the descendants of the 1922 refugees from Black Sea Turkey (Gr. Pontos), and their identity discourse of ethno-regionalism. Parakathi references nightlong sessions of friendly socialization, social drinking, and dialogical participatory singing that take place informally in coffee houses, taverns, and households. Parakathi performances are reputed for their strong Pontic aesthetics, traditional character, rich and aesthetically refined repertoire, and intense emotionality. Singing in parakathi performances emerges spontaneously from verbal socialization and emotional saturation. Singing is described as a confessional expression of deeply personal feelings -

~········R.~·~~~ Fiber-Head Connector ______Grating Region

111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007507891B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,507,891 B2 Lau et al. (45) Date of Patent: Mar. 24,2009 (54) FIBER BRAGG GRATING TUNER 4,563,931 A * 111986 Siebeneiker et al. .......... 841724 4,688,460 A * 8/1987 McCoy........................ 841724 (75) Inventors: Kin Tak Lau, Kowloon (HK); Pou Man 4,715,671 A * 12/1987 Miesak ....................... 398/141 Lam, Kowloon (HK) 4,815,353 A * 3/1989 Christian ..................... 841724 5,012,086 A * 4/1991 Barnard ................... 250/222.1 (73) Assignee: The Hong Kong Polytechnic 5,214,232 A * 5/1993 Iijima et al. ................... 841724 5,381,492 A * 111995 Dooleyet al. ................. 385112 University, Kowloon (HK) 5,410,404 A * 4/1995 Kersey et al. ............... 356/478 5,684,592 A * 1111997 Mitchell et al. ............. 356/493 ( *) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,848,204 A * 12/1998 Wanser ........................ 385112 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5,892,582 A * 4/1999 Bao et al. ................... 356/519 U.S.c. 154(b) by 7 days. 6,201,912 Bl * 3/2001 Kempen et al. ............... 385/37 6,274,801 Bl * 8/2001 Wardley.. ... ... ..... ... ... ... 841731 (21) Appl. No.: 11/723,555 6,411,748 Bl * 6/2002 Foltzer .......................... 38517 6,797,872 Bl 9/2004 Catalano et al. (22) Filed: Mar. 21, 2007 6,984,819 B2 * 112006 Ogawa .................. 250/227.21 7,002,672 B2 2/2006 Tsuda (65) Prior Publication Data 7,015,390 Bl * 3/2006 Rogers . ... ... ... ..... ... ... ... 841723 7,027,136 B2 4/2006 Tsai et al. -

Traditional Armenian Instrumental Music That Was Lacking Has Finally Arrived!

GERARD MADILIAN TRADITIONAL ARMENIAN INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC Jan. 2020 GERARD MADILIAN TRADITIONAL ARMENIAN INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC 1 2 FOREWORD Transmitted from generation to generation, and moving away from its rural origins to perpetuate itself in an urban context, Armenian traditional music has not lost its original strength. History has buried many secrets along the way, but we will try to gather together this heritage through the work of passionate musicologists. This work is neither a manual nor an encyclopedia, but instead presents a synthesis of knowledge acquired over time. It is dedicated to all those who wish to discover or better understand this unusual musical universe. Armenian words transcribed into English (phonetic of Eastern Armenian) will be indicated with a capital first letter and will remain in the singular. The author 3 4 PREFACE The long-awaited book on traditional Armenian instrumental music that was lacking has finally arrived! As my long-time friend Gerard Madilian wrote in his foreword: "History has buried many secrets along the way." It was thus urgent to share the fruits of this research with the general public, and that is why this work was deliberately written in French and translated into English, to make it widely available to as many people as possible. This book is a digest including the essential elements needed to form an opinion in this area. The specialized website www.armentrad.org was in fact selected by the author for this purpose of dissemination. I have shared the same passion with Gerard for many years, having myself practiced the Tar within the Sayat Nova ensemble, which was a traditional Armenian ensemble founded in Paris in 1965. -

Jouhikko: an Instrumental Evolution

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Honors Theses Student Scholarship Fall 2017 Jouhikko: An Instrumental Evolution Rachel E. Bracker Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Bracker, Rachel E., "Jouhikko: An Instrumental Evolution" (2017). Honors Theses. 454. https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses/454 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jouhikko: An Instrumental Evolution Submitted December 11, 2017 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of HON 420 Eastern Kentucky University Fall 2017 By: Rachel Bracker Mentor Dr. Timothy Smit Department of History i Abstract Title: Jouhikko: An Instrumental Evolution Author: Rachel Bracker Mentor: Dr. Timothy Smit, Department of History The Jouhikko is a unique instrument from Finland that has been in use since around the twelfth century. The Jouhikko is a member of the bowed lyre instrumental family, and its origin is surrounded in mystery and uncertainty. However, references to the Jouhikko, and instruments which could be potentially related to it, can be found in the Finnish epic the Kalevala and in archaeological sites throughout the Scandinavian region. The first portion of this project investigates the evolution of the Jouhikko over time. This is done by examining the history of instruments with similar designs and/or construction, such as the Gusli and the Erhu, as well as looking into the evolution of the bow. -

Çok Sesli Türk Müziği Bestecilerinin Eserlerinde

The Journal of Academic Social Science Studies International Journal of Social Science Doi number:http://dx.doi.org/10.9761/JASSS7988 Number: 74 , p. 271-287, Spring 2019 Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Yayın Süreci / Publication Process Yayın Geliş Tarihi / Article Arrival Date - Yayın Kabul Tarihi / Article Acceptance Date 22.01.2019 05.03.2019 Yayınlanma Tarihi / The Published Date 25.03.2019 ÇOK SESLİ TÜRK MÜZİĞİ BESTECİLERİNİN ESERLERİNDE MAKAM OLGUSU: DÖRT TÜRK BESTECİSİNDEN DÖRT ÖRNEK ÜZERİNE BİR ÇALIŞMA MAKAM IN THE WORKS OF TURKISH POLYPHONIC MUSIC COMPOSERS: A STUDY OF FOUR EXAMPLES FROM FOUR COMPOSERS Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Mustafa Eren Arın ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8762-2002 Ondokuz Mayıs Üniversitesi, Devlet Konservatuvarı, [email protected] Öz Türk Çoksesli Müziği bugünden geriye bakıldığında en azından 150 senelik bir geçmişe sahiptir. 19. Yüzyılın ortalarına doğru gelindiğinde Mehterhane büyük oranda Batı Bandosu tarafından yerinden edilmişti ki bu, batılılaşma hareketi olarak adlandırı- lan eğilimin bir parçası olarak 1839 yılında ilan edilen Tanzimat fermanı ile açığa çıkmış ve Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun sosyal ve politik hayatında yaşanan birçok radikal deği- şiklikle hayata geçmişti. Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun son on yıllarında devam edip ni- hayetinde 1923'te Cumhuriyetin kurulmasına zemin teşkil eden sosyal ve politik alanda yaşanan değişim süreci boyunca, çok sesli müzik ve onun türleri hızlı bir biçimde sanat- sal ifadenin taşıyıcılarına dönüşerek Feodal toplumdan Burjuva toplumuna geçişin ve eskinin değerlerinin yeninin değerleriyle yer değiştirdiğinin göstergesi oldular. O za- mandan beri Türkiyede Çoksesli Müzik besteciliğinin temel amacı Kültürel ögeleri içeri- sinde barındıran yeni Modern müzik formları yaratmak olmuştur. Bu çalışmamda, çeşit- li dönemlerden seçtiğim Türk Modern ve Çağdaş Bestecilerinin eserlerini teknik yönden incelemeye çalışacağım.