R.H. Ives Gammell and His Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRAWING and PAINTING FINAL PROJECT Mrs. J. Spadaro DUE MAY 11, 2016

DRAWING AND PAINTING FINAL PROJECT Mrs. J. Spadaro DUE MAY 11, 2016 Select an Art Movement: Classical Realism, Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Fauvism Select a Topic: A STILL LIFE FEATURING A COLLECTION OF OBJECTS: Choose ONE: 1. Sweet treats - candies, desserts, fruits – arranged in an interesting composition or looked upon from an unusual point of view 2. Natural objects – shells, pinecones, plant materials, etc arranged in an interesting composition OR A SELF PORTRAIT featuring yourself on an interesting background – a map that can showcase your heritage, the place you live now or a place that holds a special meaning to you; sheet music of a favorite song; newspaper with a meaningful article, etc. OR A well developed LANDSCAPE showcasing a particular season and including an interesting foreground, middle ground and background – no sunsets, simple beach scenes Refer to your text for reference… Pay close attention to your total work: drawing, composition, design elements, technique and color usage if applicable… remember, it is your final exam and will be graded as such. YOU MAY NOT WORK FROM PHOTOS UNLESS THEY ARE YOUR OWN REFERENCE. Draw or paint your subject influenced by the styles and artists in your selected movement. You may focus on one or more artists within that movement. Decide how you will treat color – achromatic or chromatic – perhaps a monochromatic study, or a color triad, perhaps neutral colors with the addition of one color, etc. Minimum size is 11” x 14 “ but keep your work stock size so that matting and framing is easy. THESE DRAWINGS MUST BE FULLY DEVELOPED, COMPLETED WORKS OF ART – not just quick sketches. -

The Rarity of Realpolitik the Rarity of Brian Rathbun Realpolitik What Bismarck’S Rationality Reveals About International Politics

The Rarity of Realpolitik The Rarity of Brian Rathbun Realpolitik What Bismarck’s Rationality Reveals about International Politics Realpolitik, the pur- suit of vital state interests in a dangerous world that constrains state behavior, is at the heart of realist theory. All realists assume that states act in such a man- ner or, at the very least, are highly incentivized to do so by the structure of the international system, whether it be its anarchic character or the presence of other similarly self-interested states. Often overlooked, however, is that Real- politik has important psychological preconditions. Classical realists note that Realpolitik presupposes rational thinking, which, they argue, should not be taken for granted. Some leaders act more rationally than others because they think more rationally than others. Hans Morgenthau, perhaps the most fa- mous classical realist of all, goes as far as to suggest that rationality, and there- fore Realpolitik, is the exception rather than the rule.1 Realpolitik is rare, which is why classical realists devote as much attention to prescribing as they do to explaining foreign policy. Is Realpolitik actually rare empirically, and if so, what are the implications for scholars’ and practitioners’ understanding of foreign policy and the nature of international relations more generally? The necessity of a particular psy- chology for Realpolitik, one based on rational thinking, has never been ex- plicitly tested. Realists such as Morgenthau typically rely on sweeping and unveriªed assumptions, and the relative frequency of realist leaders is difªcult to establish empirically. In this article, I show that research in cognitive psychology provides a strong foundation for the classical realist claim that rationality is a demanding cogni- tive standard that few leaders meet. -

P Ablo P Icasso

operagallery.com Pablo Picasso September 2015 18 September - 18 October 2015 2 Orchard Turn # 04-15 ION Orchard 238801 Singapore T. + 65 6735 2618 - [email protected] Opening Hours Weekdays: 11 am - 8 pm • Weekends: 10 am - 8 pm Preface 2015 marks the 50th Anniversary of Singapore’s independence, and such a substantial milestone calls for an exhibition of equal merit. It is with this in mind that we are proud to showcase one of the most illustrious names in 20th century art: Pablo Picasso. Heralded as one of the biggest names of Modern Art and one of the pioneers of Cubism, Picasso dramatically changed the landscape of his contemporary art scene. Excelling in various mediums and movements, Picasso strived to cast aside conventional ideals, driving forward and exploring new limits all the while establishing himself as one of the most important figures within the art world. 3 We are pleased to present to you these prestigious works by the world’s most illustrious and recognizable Modern artist, in an intimate setting for collectors and appreciators alike. Gilles Dyan Stéphane Le Pelletier Founder and Chairman Director Opera Gallery Group Opera Gallery Asia Pacific Researching an illustrious figure such as Picasso is bound to elicit an array of polarizing definitions. The life of Pablo Picasso began in Málaga, Spain on October 25th in 1881. Not a particularly bright ‘Genius’, surely, is one that repeats itself often, ‘visionary’ another. Tormented, manipulative, student academically, at the age of eight Pablo was already displaying signs of artistic aptitude, a misanthropic – also phrases that pepper history’s perception of the persona, a man whose namesake talent his artistic parents recognized and encouraged. -

TRADITIONS & D E P a R T U R

REALISM NOW : TRADITIONS & D e p a r t u r e s M entors and P rotégés JOEL BABB chung shil adams • PETER BOUGIE barbara allen • LEWIS COHEN benjamin cariens jeff slomba • ARTHUR DECOSTA deborah deichler paul dusold • NEIL DREVITSON janice drevitson • LARRY FRANCIS frank depascale • ROBERT HUNTER sergio roffo • SIDNEY HURWITZ andrew raftery • PAUL INGBRETSON lindesay harkness • RICHARD LACK allan banks • LISA LEARNER geronna lewis • DAVID LOWREY sam vokey • DOUGLAS MARTENSON david campbell jess montgomery • MAUREEN MCCABE katy wood • GEORGE NICK shalom flash • ELLIOT OFFNER andrew devries • RICHARD RAISELIS sedrick huckaby REALISM NOW : • GLENN RUDDEROW david baker • TRADITIONS & D e p a r t u r e s SUSAN STEPHENSON nathan lewis • ANDREW WYETH M ENTORS AND P ROTÉGÉS jamie wye1th carolyn wyeth REALISM NOW : TRADITIONS & De p a rtu r es M ENTORS AND P ROTÉGÉS Part I Artists from New England, greater Philadelphia, and greater Minneapolis November 24, 2003 to January 17, 2004 vose NEW AMERICAN REALISM contemporary R EALISM N OW : T RADITIONS AND D EPARTURES , M ENTORS AND P ROTÉGÉS Part I, Artists from New England, greater Philadelphia and greater Minneapolis November 24, 2003 to January 17, 2004 Compiled by Nancy Allyn Jarzombek Essay by Trevor J. Fairbrother Catalogue designed by Claudia Arnoff Abbot W. Vose and Robert C. Vose III, Co-Presidents Marcia L. Vose, Director, Vose Contemporary Lynnette Bazzinotti, Business Manager Carol L. Chapuis, Director of Administration Nancy Allyn Jarzombek, Director of Research Siobhan M. Wheeler, Associate for Research Julie Simpkins, Artist-in-Residence, Preparator Courtney S. Kopplin, Assistant to the Gallery Manager Claudia G. -

Classical Realism in the Age of Globalization

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 2009 Paradigmatic recrudescence: Classical realism in the age of globalization Nerses Kopalyan University of Nevada Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Kopalyan, Nerses, "Paradigmatic recrudescence: Classical realism in the age of globalization" (2009). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 127. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1384947 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARADIGMATIC RECRUDESCENCE: CLASSICAL REALISM IN THE AGE OF GLOBALIZATION by Nerses Kopalyan Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2006 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Master of Arts in Political Science Department of Political Science College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2009 Copyright by Nerses Kopalyan 2010 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by Nerses Kopalyan entitled Paradigmatic Recrudescence: Classical Realism in the Age Globalization be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Political Science Jonathan R. -

Download Article (PDF)

International Conference on Industrial Technology and Management Science (ITMS 2015) A Dissertation on the Personalization Features of Freud's Painting Language Shaojie Zhang & Jing xi Zhengzhou Huaxin University, Xinzheng, Zhengzhou ABSTRACT: Lucian Freud is one of the representative artists in the field of contemporary realism painting field. Freud's painting language and image expression of its own style that has a great influence on the contemporary realism painting. His works reach a perfect unification in the texture and structure, space, volume, color painting factors. the picture shows a unique aesthetic value to people. The works have a highly personalized style. Freud's paintings have profound meaning to the spread of the traditional realistic painting, it also has progressive significance to the development of modern art. KEYWORD: Realism painting; Expression; Personalized 1 INTRODUCTION perception of the world that keep a special perception ability. This perception ability will be With the development of western modern painting, brought into the picture, become his own bright all kinds of painting are colorful. Freud is insist symbol. committed to the research of realistic painting. He Freud into st union painting school in 1939, discribe the state of modern people, formed a unique trained bythe principal morris. This time his painting "freudian" spirit of the painting language. This theme is broad that influence of surrealism. The article attempts to express the spirit of the emotionas painting is delicate and detail, then it began to have in contemporary realism painting language and the some sensitive. unique personalized features through the From the 40 s to 80 s, he settled in London, introduction of Freud's resume, the development of whether as an artist or ordinary people, Freud are artistic style, and its personalized style supposed to be hard to get along with. -

The Natural School As a Stage in the Development of Russian Literature

JURIJ V. MANN THE NATURAL SCHOOL AS A STAGE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF RUSSIAN LITERATURE Attempts to give an overall and comprehensive definition to different literary epochs (like Renaissance, Baroque, Classi- cism, etc.) have been made time and again from time immemo- rial. And in spite of the debatable and inconclusive nature of the results, such attempts are certainly fairly fruitful. This parti- cularly applies to what has been done with regard to Romanti- cism. Romanticism by its very essence is perceived by us as some- thing multi-faceted, fluctuating and elusive. Nevertheless, the urge to understand and describe it as an integral whole, at least within the confines of one national literature, never palls. I shall remind the reader of some classical experiences in the field: the conception of Romanticism in terms of style-an unlimited and boundless perspective which superseded the limited and rounded perspective of the Classicist pattern (F. Strichl); or in terms of the treatment of some philosophical or human concerns like love (P. Kluckhohn ~) or death (W. Rehm3); or in terms of the whole complexity of human and artistic problems (cf. the idea of the synthesis of the opposites 1 Strich Fritz., Deutsche Klassik und Romantik oder VoUendung und Unendlichkeit. Ein Vergleich. III Auflage. Mfinchen, 1928. 2 Kluckhohn Paul, Die Auffassung der Liebe in der Literatur des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts und in der Romantik. Halle, 1922. 3 Rehm Walter, Der Todesgedanke in der deutschen Dichtung vom Mittelalter bis Romantik. Halle/Saale, 1928. Neoheticon XV/1 Akaddmiai Kiad6, Budapest John Benjamins B. V., Amsterdam 90 JURIJ V. -

Ed Stitt My First Forty Years: Paintings & Drawings

Ed Stitt My First Forty Years: Paintings & Drawings 1 Ed Stitt My First Forty Years: Paintings & Drawings Published on the occasion of the 2016 exhibition, Ed Stitt My First Forty Years: Paintings and Drawings at The Barrington Center for the Arts, Gordon College, Wenham MA. Gallery NAGA 67 Newbury Street Boston, Massachusetts 02116 www.gallerynaga.com cover: Back Bay Skyline 1991 oil on linen 22x52" 2 [A] tradition must be a living thing to which each generation of Introduction practitioners makes a contribution, otherwise it becomes an historic artifact preserved but ultimately no longer vital. Karen L. Mulder Art Historian Dorothy Abbott Thompson (1986) Historians of American topics make note of one distinctively American trait: a tendency to revitalize old forms by synthesizing traditional and contemporary styles. Synthesis requires a seedbed of cultural support to take root. By the mid-twentieth century, realism had lost ground in the critical dialogue, colliding with an assertive if not absolutist stream of art criticism and practice that demanded independence from close observation and refined technique. The Boston School painters, technically anchored to the seedbed of 19th-century French realism, attained distinction by combining strictly classical Beaux Arts standards with the lively palette and energetic brushwork of the Impressionist movement they absorbed in Paris firsthand, during the 1880s. By the mid-twentieth century, however, American realism had mostly lost ground to an assertive, if not absolutist, stream of art criticism and practice that pulled close observation and refined technique out of the picture by the roots. Critical respect for the exacting expectations of classical realism, which had been evaporating since the 1920s, entirely disappeared; elite commentators dismissed the life’s work of several generations of pictorial realists as passé and retardataire. -

The Tension of the Real: Visuality in Nineteenth Century British Realism

THE TENSION OF THE REAL: VISUALITY IN NINETEENTH CENTURY BRITISH REALISM by AMANDA L. CORNWALL A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Comparative Literature and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Amanda L. Cornwall Title: The Tension of the Real: Visuality in Nineteenth Century British Realism This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Comparative Literature by: Professor Forest Pyle Chairperson Professor Kenneth Calhoon Core Member Assistant Professor Heidi Kaufman Core Member Associate Professor Martin Klebes Institutional Representative and Professor Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2015 ii © 2015 Amanda L. Cornwall iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Amanda L. Cornwall Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature June 2015 Title: The Tension of the Real: Visuality in Nineteenth Century British Realism This dissertation begins from the problem that is built into realism as a literary genre: its commitment to capturing the unfiltered circumstances of human life will always be at odds with the artifice of its representational constructs and its fiction. In this study, I consider visuality as a central, productive part of this problem and seek intensely visual moments within realist novels where realism wages its own struggle with itself as it attempts to navigate its limitations and push forward its possibilities. These moments pause the narrative as they prioritize picture over action. -

Nietzsche on Realism in Art and the Role of Illusions in Life-Affirmation." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2017

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Philosophy Theses Department of Philosophy 12-11-2017 Nietzsche on Realism in Art and the Role of Illusions in Life- Affirmation Marie K. Le Blevennec Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_theses Recommended Citation Le Blevennec, Marie K., "Nietzsche on Realism in Art and the Role of Illusions in Life-Affirmation." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_theses/222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Philosophy at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NIETZSCHE ON REALISM IN ART AND THE ROLE OF ILLUSIONS IN LIFE- AFFIRMATION by MARIE KERGUELEN LE BLEVENNEC Under the Direction of Jessica Berry, PhD ABSTRACT In this paper, I investigate Nietzsche’s views about realism in art, and use the resulting textual evidence to explain the connection between realism, health and life-affirmation. First, I show that Nietzsche’s contrasting claims about artists like Flaubert and Stendhal reflect a distinction between two types of realism: the unhealthy realism of Flaubert, and the healthy realism of Stendhal. I then use this understanding of healthy realism in art to argue that for Nietzsche, healthy realism is vital for life-affirmation. Finally, I apply this evidence to a debate between Daniel Came and Bernard Reginster concerning whether Nietzsche thinks life- affirmation requires falsifying reality using illusions, especially artistic illusions, for the purpose of masking life’s terrible truths. -

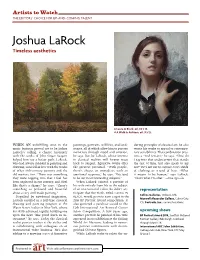

Artists to Watch the Editors’ Choice for Up-And-Coming Talent

Artists to Watch The ediTors’ choice for up-and-coming TalenT Joshua LaRock Timeless aesthetics Laura in Black, oil, 20 x 16. A Walk in Autumn, oil, 9 x 12. When an unfulfilling stint in the paintings, portraits, still lifes, and land- during principles of classical art, he also music business proved not to be Joshua scapes, all of which allow him to portray wants his works to appeal to contempo- LaRock’s calling, a chance encounter narratives through mood and emotion, rary sensibilities. That combination pres- with the works of John Singer Sargent he says. But for LaRock, whose interest ents a “real tension,” he says. “How do helped him see a better path. LaRock, in classical realism will forever trace I tap into that undercurrent that stands who had always dabbled in painting and back to Sargent, figurative works offer the test of time, but also speak to my drawing, soon fell in love with the works the greatest potential. “With people, era?” He’s not out to capture every stitch of other 19th-century painters and the there’s always an immediacy with an of clothing or strand of hair. “What old masters, too. “There was something emotional response,” he says. “We tend it means to be human,” says LaRock, they were tapping into that I feel has to be our most interesting subjects.” “that’s what I’m after.” —Kim Agricola been neglected in our century, and I feel When LaRock painted a portrait of like that’s a shame,” he says. “There’s his wife entirely from life as the subject something so profound and beautiful of an instructional video, he didn’t an- representation about a very well-made painting.” ticipate that the work, titled LAURA IN Collins Galleries, Orleans, MA; Propelled by newfound inspiration, BLACK, would go on to earn a spot in the Maxwell Alexander Gallery, Culver City, LaRock enrolled in a full-time classical 2016 BP Portrait Award competition. -

AP Studio Summer Assignments

AP Studio Summer Assignments 1. AP Studio Process Portfolio (300pts): complete 15 organized 2 page spread images of work • Purchase a hardbound sketchbook; no perforated pages, 8 1/2 x 11 (Michaels, Hobby Lobby, etc) • Number pages both front and back. No pages get skipped. Work in order. • Balance 50% text and 50% images on each page. Include titles on page tops! • Page images may be printed in color, drawn, or both. I prefer at least SOME drawing. Drawing builds skills and helps you see more carefully. • Write left to right, horizontally, and legibly. • Choose topics you are interested in and/or inspired by. We will be using these throughout the school year to create composition for your final portfolio. Assignments: Art Movements • Create 5 or more double sided pages of investigation based on 5 art movements or cultural arts. -Choose ones you relate to. Choose your own or refer to the list provided. Artists: • Create 5 or more double sided pages of investigation based on 5 artists you admire or are inspired by. -Choose ones you can relate to. Choose your own or refer to the list provided. Try to research ones you don’t know. Sketches/ techniques: • Create 5 or more pages of observational sketches and drawings based on different techniques or materials. Use Different collage papers and drawing/ painting mediums to explore a variety of outcomes. All research pages must be completed by August 9th and posted in Google Classroom. 2. Art Museum or Art Gallery Visit (100pts): Visit a Gallery or Museum of your choice anywhere, locally or while on vaccation somewhere.