A Million Matzo Balls a GREAT JEWISH BOOKS TEACHER WORKSHOP RESOURCE KIT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

The Laws of Shabbat

Shabbat: The Jewish Day of Rest, Rules & Cholent Meaningful Jewish Living January 9, 2020 Rabbi Elie Weinstock I) The beauty of Shabbat & its essential function 1. Ramban (Nachmanides) – Shemot 20:8 It is a mitzvah to constantly remember Shabbat each and every day so that we do not forget it nor mix it up with any other day. Through its remembrance we shall always be conscious of the act of Creation, at all times, and acknowledge that the world has a Creator . This is a central foundation in belief in God. 2. The Shabbat, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, NCSY, NY, 1974, p. 12 a – (אומן) It comes from the same root as uman .(אמונה) The Hebrew word for faith is emunah craftsman. Faith cannot be separated from action. But, by what act in particular do we demonstrate our belief in God as Creator? The one ritual act that does this is the observance of the Shabbat. II) Zachor v’shamor – Remember and Safeguard – Two sides of the same coin שמות כ:ח - זָכֹוראֶ ת יֹום הַשַבָתלְקַדְ ׁשֹו... Exodus 20:8 Remember the day of Shabbat to make it holy. Deuteronomy 5:12 דברים ה:יב - ׁשָמֹוראֶ ת יֹום הַשַבָתלְקַדְ ׁשֹו... Safeguard the day of Shabbat to make it holy. III) The Soul of the Day 1. Talmud Beitzah 16a Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish said, “The Holy One, Blessed be He, gave man an additional soul on the eve of Shabbat, and at the end of Shabbat He takes it back.” 2 Rashi “An additional soul” – a greater ability for rest and joy, and the added capacity to eat and drink more. -

Over 100 More Deals on Our Shelves! Not All Sales Items Are Listed

Sales list 3/13 - 4/2 Bulk Department Product Name Size Sale Coupons Bulk Organic Green Lentils Per Pound 1.99 Bulk Organic Hulled Millet Per Pound 1.19 Equal Exchange Select Organic Coffee Per Pound 8.99 Fantastic Foods Falafel Mix Per Pound 3.39 Fantastic Foods Hummus Mix Per Pound 4.39 Fantastic Foods Instant Black Beans Per Pound 4.39 Fantastic Foods Instant Refried Beans Per Pound 4.39 Fantastic Foods Vegetarian Chili Mix Per Pound 4.39 Grandy Oats Coconut Granola Per Pound 8.99 Woodstock Dark Chocolate Almonds Per Pound 11.69 Refrigerated Product Name Size Sale Coupons Brown Cow Cream Top Yogurt 5.3-6 oz 4/$3 Earth Balance Buttery Sticks, Original and Soy-Free 16 oz 3.69 Earth Balance Natural Buttery Spread 15 oz 3.69 Earth Balance Organic Whipped Buttery Spread 13 oz 3.69 Earth Balance Organic Coconut Spread 10 oz 3.69 Earth Balance Soy-Free Buttery Spread 15 oz 3.69 Earth Balance Omega-3 Spread 13 oz 3.69 Field Roast Celebration Roast 2 lb 12.99 Field Roast Celebration Roast 1 lb 5.99 Field Roast Hazelnut-Cranberry Stuffed Roast 2 lb 16.99 Florida’s Natural Orange Juice 59 oz 3.69 Follow Your Heart Vegan Egg Powder 4 oz 5.99 Green Valley Organics Lactose-Free Yogurt 24 oz 3.99 Green Valley Organics Lactose-Free Cream Cheese 8 oz 2.99 Hail Merry Macaroon Bites 3.5 oz 2.69 Hail Merry Miracle Tarts 3 oz 2.99 Harmless Harvest Organic Raw Coconut Water 16 oz 3.99 Harmless Harvest Organic Raw Coconut Water 32 oz 7.99 Immaculate Baking Company Flaky Biscuits 16 oz 2/$5 Immaculate Baking Company Cinnamon Rolls 17.5 oz 3.69 Immaculate -

Zola.’ (AP) Song of the Summer

ARAB TIMES, THURSDAY, JULY 1, 2021 NEWS/FEATURES 13 People & Places Music Dacus sings young love Cat album falters at fi rst but ends strong By Mark Kennedy ot to be totally catty, but Doja Cat’s third album Nstarts poorly. The first four songs — “Woman,” “Naked,” “Payday” with Young Thug and “Get Into It (Yuh)” — are half-baked tunes mimicking beats and vocals from Nicki Minaj or Rihanna. None are note- worthy. It’s depressing. What happened to the artist behind 2019s “Hot Pink,” a sonic breath of fresh air? What happened to the Doja Cat whose electric performance of “Say So” at the Grammys was reminiscent of Missy Elliott’s futurism? Just wait. The fi fth song, “Need to Know,” is a superb, steamy sex tape of a song (with Dr. Luke co-writing and producing) and the sixth, “I Don’t Do Drugs” featuring Ariana Grande, is airy and confi dent with heav- enly harmonies. “Love to Dream” follows, a slice of dreamy pop, and then The Weeknd stops by on a terrifi c, slow-burning “You Right.” Cat The Cat is back. From then on, the 14-track “Planet Her” rights itself with whispery pop songs and the envelope-pushing “Options” with JID, climaxing with the awesome “Kiss Me More,” the previously released single with SZA that has a Gwen Stefani-ish refrain and must be considered a strong contender for This image released by A24 shows Riley Keough, (left), and Taylour Paige in a scene from ‘Zola.’ (AP) song of the summer. Despite the weak start, Doja Cat fulfi lls her promise on “Planet Her,” with an exciting, unpredictable style and a vocal ability that can switch from buttery sweet- Film ness to cutting raps. -

FCC Quarterly Programming Report Jan 1-March 31, 2017 KPCC-KUOR

Southern California Public Radio- FCC Quarterly Programming Report Jan 1-March 31, 2017 KPCC-KUOR-KJAI-KVLA START TIME Duration min:sec Public Affairs Issue 1 Public Affairs Issue 2 Show & Narrative 1/2/2017 TAKE TWO: The Binge– 2016 was a terrible year - except for all the awesome new content that was Entertainment Industry available to stream. Mark Jordan Legan goes through the best that 2016 had to 9:42 8:30 offer with Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: The Ride 2017– 2017 is here and our motor critic, Sue Carpenter, Transportation puts on her prognosticator hat to predict some of the automotive stories we'll be talking about in the new year 9:51 6:00 with Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: Presidents and the Press– Presidential historian Barbara Perry says contention between a President Politics Media and the news media is nothing new. She talks with Alex Cohen about her advice for journalists covering the 10:07 10:30 Trump White House. TAKE TWO: The Wall– Political scientist Peter Andreas says building Trump's Immigration Politics wall might be easier than one thinks because hundreds of miles of the border are already lined with barriers. 10:18 12:30 He joins Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: Prison Podcast– A podcast Law & is being produced out of San Quentin Media Order/Courts/Police State Prison called Ear Hustle. We hear some excerpts and A Martinez talks to 10:22 9:30 one of the producers, Nigel Poor. TAKE TWO: The Distance Between Us– Reyna Grande grew up in poverty in Books/ Literature/ Iguala, Mexico, left behind by her Immigration Authors parents who had gone north looking for a better life and she's written a memoir for young readers. -

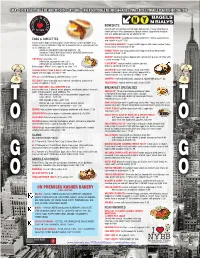

Nybb Togo Menu 2019.Indd

BENEDICTS Served with two gently poached eggs, housemade cheesy hollandaise & choice of home fries, tomatoes or cottage cheese. Upgrade to seasonal fruit or a potato pancake for an additional .99 SOUTHWESTERN* jalapeño bialy topped with beef chorizo, queso fresco EGGS & OMELETTES and chipotle drizzle 11.99 Served with a bagel or bialy & plain cream cheese. Choice of home fries, cottage cheese or tomatoes. Upgrade to seasonal fruit or a potato pancake CALIFORNIA BENEDICT* English muffin topped with house roasted turkey for an additional .99 breast, bacon and avocado 12.49 substitute EGG WHITES OR EGG BEATERS® .99 HUMBLE HASH* two crisp potato latkes topped with our housemade substitute TURKEY BACON or TURKEY SAUSAGE for breakfast corned beef hash 13.49 meat at no additional charge. REUBEN* toasted rye bread topped with corned beef & kraut, drizzled with TWO EGGS* any style. 7.49 russian dressing 12.49 with bacon, sausage or ham. 9.99 with brisket or corned beef hash. 10.49 FLORENTINE* toasted challah, sautéed spinach, Extra hungry? Make it three eggs for an extra 1.49 onions & sprinkled with feta 11.99 CHICKEN FRIED STEAK & EGGS* with home fries, smothered in gravy COLORADO* warm flour tortillas, steak and refried topped with two eggs any style 12.99 beans smothered in green chili gravy, topped with a chipotle drizzle and a sprinkle of cheddar 13.99 LEO Lox, scrambled eggs & sautéed onions. 12.99 COUNTRY* fresh baked biscuits, sausage & housemade gravy 11.99 DELI EGGS* three eggs with your choice of corned beef, pastrami or salami scrambled -

T E M P L E B E T H a B R a H a M Sale of Chametz Form on Page 17

the Volume 32, 31, Number Number 7 7 March 2013 2012 TEMPLE BETH ABRAHAM AdarAdar/Nisan / Nisan 5773 5772 R i Sale of Chametz Form on page 17 Pu M directory TEMPLE BETH ABRAHAM Services Schedule is proud to support the Conservative Movement by Services/ Time Location affiliating with The United Synagogue of Conservative Monday & Thursday Judaism. Morning Minyan Chapel 8:00 a.m. Friday Evening (Kabbalat Shabbat) Chapel 6:15 p.m. Advertising Policy: Anyone may sponsor an issue of The Omer and receive a dedication for their business or loved one. Contact us for details. We do Shabbat Morning Sanctuary 9:30 a.m. not accept outside or paid advertising. The Omer is published on paper that is 30% post-consumer fibers. Candle Lighting (Friday) The Omer (USPS 020299) is published monthly except July and August March 1 5:45 p.m. by Congregation Beth Abraham, 336 Euclid Avenue, Oakland, CA 94610. March 8 5:52 p.m. Periodicals Postage Paid at Oakland, CA. March 15 6:59 p.m. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to The Omer, c/o Temple Beth March 22 7:05 p.m. Abraham, 336 Euclid Avenue, Oakland, CA 94610-3232. © 2013. Temple Beth Abraham. The Omer is published by Temple Beth Abraham, a non-profit, located at Torah Portions (Saturday) 336 Euclid Avenue, Oakland, CA 94610; telephone 510-832-0936. It is March 2 Ki Tisa published monthly except for the months of July and August for a total of March 9 Vayakhel-Pekudei ten issues per annum. It is sent as a requester publication and there is no March 16 Vayikrah paid distribution. -

Tasty Chocolate Seder April 6 Th , 2020 Dessert Recipe E-Book

TaSTY Chocolate Seder April 6 th, 2020 Dessert Recipe e-book Coconut Macaroons with Chocolate Drizzle Chocolate Covered Matzo Toee Flourless Chocolate Cake Passover Blondies Chocolate Covered Strawberries Coconut Macaroons with Chocolate Drizzle Ingredients: - 1 7oz bag of coconut - 1 egg, beaten - ¼ cup of sugar - 3 tbs. Melted margarine - Melted chocolate Steps: - Mix all ingredients together in a large bowl - Drop spoonfuls onto a greased cookie sheet, you can shape them with your fingers a little - Bake at 325 for 20 minutes and let cool for 1-2 min and then remove them from sheet - Spoon or drizzle melted chocolate of your choice on top of macaroons (tip: pour melted chocolate in a ziploc baggie, snip o corner and drizzle over macaroons) Chocolate Covered Matzo Toee Ingredients: - 3 to 4 pieces of matzo (enough to fill 2 cookie sheets) - 2 sticks of butter - 1 cup of brown sugar - Chocolate chips (any kind!) Steps: - Preheat oven to 400 degrees F - Line 2 cookie sheets with foil and place matzo on sheets, you may need to break some pieces to have it all fit - Put butter and brown sugar in a pot on stove at low heat, simmer for 5 minutes and whisk until fully blended - Pour butter/brown sugar mixture over matzo and bake in oven for about 5 minutes, or until bubbly - Take matzo out of oven and sprinkle with chocolate chips, spread with spatula to cover - Leave it plain or top with sea salt, M&Ms, nuts or any topping of choice! - Let cool in fridge for 45 minutes, then break into pieces Flourless Chocolate Cake Ingredients: - 2 sticks of butter, cut into pieces - 8 ounces semisweet chocolate chips (about 1.5 cups) - 1 ¼ cups sugar - 1 cup sifted unsweetened cocoa powder - 6 large eggs Steps: - Preheat oven to 350 degree F - Butter 10- inch springform pan. -

Latina Costume Designer Mildredbrignoni

Mildred Brignoni Costume Designer Union Local 892/705 323 819-1536 [email protected] Feature Films and TV Director Production Company Deep Stage Costume Designer Robert Beaumont Badhouse Studios LLC Valerian and the City Of a Thousand Luc Besson Rough Around The Edges Producer Planets ( Stylist to Herbie Hancock) David Sanger Line Producer Ben Silent Life Costume Designer Vlad Kozlov DreamerMurphy Pictures Banana Split Ben Kasulke Produced by Eskimo Sisters LLC - Assistant Costume Designer - Glen Trotiner, Will Phelps, Jeremy Mona May Glarelick Marshall Reginald Hudlin Complete Costume look 1 and 4 of Assistant Costume Designer-Ruth Chadwick Boseman; Producers E.Carter Jonathan Sanger and Paula Wagner Chapter And Verse Jamal Joseph Producers Jonathan Sanger and Cheryl Assistant Costume Designer Hill Wannabes William DeMao & Artisan Entertainment - William Costume Designer Charles Adessi DeMao & Charles Adessi Home Invaders Greg Wilson Spike Lee Joint/ Arch Angel Ent Costume Designer The Other Brother Mandel Holland Xenon Ent./ Delflix Pictures - Mandel Costume Designer Holland Blazin Marcos Miranda Ground Zero Ent./ Miranda Productions- Costume Designer Marcos Miranda Full Court Press Jamal Joseph Horizon Productions-Jamal Joseph Co-Costume Designer A Pocket Full Of Dreams Vishal Buhndari Kasuri Productions Inc- Vishal Costume Designer Buhndari, Evan Seplow. Manhattan Chase Godfrey Ho Gramwell Pictures - Godfrey Ho The Chris Rock Show Scott Preston HBO / Nelson George Stylist Forensic Files - Stylist Richard Court TV/ Three Hearts -

Passover Catering 2021

Orders must be placed by 12PM two days prior to pickup or delivery. Order requests submitted within 24 hours of pickup/delivery Passover time are subject to availability Catering We recommend ordering early to secure your preferred date and time 2021 DELIVERY Delivery is available depending on order size and distance PICKUP Orders can be picked up during regular business hours MODIFICATIONS We are unable to accommodate half-orders or modify for dietary restrictions REHEATING Food is intended for in-home reheating and FRIDAY 3/26 – SUNDAY 4/4 will come with easy reheating instructions ORDER ONLINE AT BEAUTYSBAGELSHOP.COM Our full catering menu (415) 992-NOSH | [email protected] is also available – just ask! 3838 TELEGRAPH AVENUE, OAKLAND, CA 94609 Holiday Basics Easy Order Complete Meal SEDER PLATE KIT $17 lamb shankbone, horseradish root, parsley, greens, egg, an orange (!), SEDER MEAL KIT charoset and Marisal sea salt (meant to fill the ceremonial seder plate) serves 4 CHAROSET 1 pint $14 roasted brisket, spring vegetables, nana's potato kugel, matzo ball soup, tart apple, honey, walnut, cinnamon, sweet wine and raisin charoset, mini coconut macaroons, box of matzo and chocolate matzo $132 CHOPPED CHICKEN LIVER half-pint $10 chicken liver, caramelized onion and shmaltz WISE SONS GEFILTE FISH 4 pieces $18 Sweets traditional recipe made with Pacific Ocean-caught fish, four pieces in broth $ CHICKEN SOUP serves 2 $9 MINI COCONUT MACAROONS dozen 13.50 just the broth - made with organic chickens and roasted vegetables gluten-free recipe with coconut, sweetened condensed milk, egg whites and wildflower honey $ MATZO BALLS 2 pieces per order 5 $ hand-made matzo balls in brine (soup sold separately) CHOCOLATE, CARAMEL & SEA SALT MATZO serves 2 9 Guittard bittersweet chocolate, caramel and Jacobsen sea salt Mains Extras ROASTED BRISKET serves 4 $36 1lb. -

Pre-Purim Happy Hour February 21 (See Page 5) Magician Eric Vaughn to Perform at the Pre-Purim Happy Hour

Jewish Community Center January/February 2018 • Tevet/Adar 5778 America’s First Ladies February 7 (see page 6) Pre-Purim Happy Hour February 21 (see page 5) Magician Eric Vaughn to perform at the Pre-Purim Happy Hour Begins January 29 (see page 13) Stephanie Baines, Aging Mastery Facilitator TheJKC.org/HeritageCenter Heritage Center The Heritage Center is a program of the Jewish Community Center of Greater Kansas City serving older adults. It is made possible with major funding from the Menorah Heritage Foundation This Calls for of Greater Kansas City, Jewish Federation of Kansas City and the United Way of Greater Kansas City. a Celebration! Office Hours 8:30am - 4:30pm The Heritage Center has officially been re-accredited by the National Institute of Senior Centers Mission The mission of the Heritage Center is to positively impact our community by creating opportunities for healthy aging in a welcoming Jewish environment. Accreditation National Institute of Senior Centers Let’s Celebrate Together Heritage Center Committee March 8 • 4:00-6:00pm Stephen Feinstein Bonnie Rosen Billie Lash Phil Rubenstein Heritage Center Loretta Levine Vivian Schlozman Efi Kamara Ann Stern Drop in to enjoy delicious Rod Minkin Mike Rogovein appetizers and live entertainment by The Don The Heritage Center Committee Warner Ensemble is an advisory committee of the Heritage Center. The purpose of the committee is to identify the needs and interests of older adults served by the Heritage The Heritage Center is committed Center and to advise The J staff to implementing quality programs and board members regarding and services. By achieving national matters of concern, priority and accreditation, our community can be potential innovation. -

2020 Sundance Film Festival: 118 Feature Films Announced

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: December 4, 2019 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] 2020 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL: 118 FEATURE FILMS ANNOUNCED Drawn From a Record High of 15,100 Submissions Across The Program, Including 3,853 Features, Selected Films Represent 27 Countries Once Upon A Time in Venezuela, photo by John Marquez; The Mountains Are a Dream That Call to Me, photo by Jake Magee; Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, courtesy of Sundance Institute; Beast Beast, photo by Kristian Zuniga; I Carry You With Me, photo by Alejandro López; Ema, courtesy of Sundance Institute. Park City, UT — The nonprofit Sundance Institute announced today the showcase of new independent feature films selected across all categories for the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. The Festival hosts screenings in Park City, Salt Lake City and at Sundance Mountain Resort, from January 23–February 2, 2020. The Sundance Film Festival is Sundance Institute’s flagship public program, widely regarded as the largest American independent film festival and attended by more than 120,000 people and 1,300 accredited press, and powered by more than 2,000 volunteers last year. Sundance Institute also presents public programs throughout the year and around the world, including Festivals in Hong Kong and London, an international short film tour, an indigenous shorts program, a free summer screening series in Utah, and more. Alongside these public programs, the majority of the nonprofit Institute's resources support independent artists around the world as they make and develop new work, via Labs, direct grants, fellowships, residencies and other strategic and tactical interventions.