THE REAL CHINESE QUESTION CHESTER HOLCOMBE H7a

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protestants in China

Background Paper Protestants in China Issue date: 21 March 2013 (update) Review date: 21 September 2013 CONTENTS 1. Overview ................................................................................................................................... 2 2. History ....................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Number of Adherents ................................................................................................................ 3 4. Official Government Policy on Religion .................................................................................. 4 5. Three Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM) and the China Christian Council (CCC) ................... 5 6. Registered Churches .................................................................................................................. 6 7. Unregistered Churches/ Unregistered Protestant Groups .......................................................... 7 8. House Churches ......................................................................................................................... 8 9. Protestant Denominations in China ........................................................................................... 9 10. Protestant Beliefs and Practices ............................................................................................ 10 11. Cults, sects and heterodox Protestant groups ........................................................................ 14 -

Chinese Protestant Christianity Today Daniel H. Bays

Chinese Protestant Christianity Today Daniel H. Bays ABSTRACT Protestant Christianity has been a prominent part of the general religious resurgence in China in the past two decades. In many ways it is the most striking example of that resurgence. Along with Roman Catholics, as of the 1950s Chinese Protestants carried the heavy historical liability of association with Western domi- nation or imperialism in China, yet they have not only overcome that inheritance but have achieved remarkable growth. Popular media and human rights organizations in the West, as well as various Christian groups, publish a wide variety of information and commentary on Chinese Protestants. This article first traces the gradual extension of interest in Chinese Protestants from Christian circles to the scholarly world during the last two decades, and then discusses salient characteristics of the Protestant movement today. These include its size and rate of growth, the role of Church–state relations, the continuing foreign legacy in some parts of the Church, the strong flavour of popular religion which suffuses Protestantism today, the discourse of Chinese intellectuals on Christianity, and Protestantism in the context of the rapid economic changes occurring in China, concluding with a perspective from world Christianity. Protestant Christianity has been a prominent part of the general religious resurgence in China in the past two decades. Today, on any given Sunday there are almost certainly more Protestants in church in China than in all of Europe.1 One recent thoughtful scholarly assessment characterizes Protestantism as “flourishing” though also “fractured” (organizationally) and “fragile” (due to limits on the social and cultural role of the Church).2 And popular media and human rights organizations in the West, as well as various Christian groups, publish a wide variety of information and commentary on Chinese Protestants. -

The Vagina Monologues by Eve Ensler

The Vagina Monologues by Eve Ensler Official guidelines and script for the V-Day 2004 College Campaign Available by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc. To order copies of the beautiful, bound acting edition of the script of “The Vagina Monologues” (the original – slightly different from the V-Day version of the script) for memento purposes, to sell at your event, or for use in theatre or other classes or workshops, please contact: Customer Service DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC. 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016 Telephone: 212-683-8960, Fax: 212-213-1539 You may also order the acting edition online at www.dramatists.com. Ask for: Book title: The Vagina Monologues ISBN: 0-8222-1772-4 Price: $5.95 Be sure to mention that you represent the V-Day College Campaign. DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC. Representing the American theatre by publishing and licensing the works of new and established playwrights. For more than 65 years Dramatists Play Service, Inc. has provided the finest plays by both established writers and new playwrights of exceptional promise. Formed in 1936 by a number of prominent playwrights and theatre agents, Dramatists Play Service, Inc. was created to foster opportunity and provide support for playwrights by publishing acting editions of their plays and handling the nonprofessional and professional leasing rights to these works. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. has grown steadily to become one of the premier play-licensing agencies in the English speaking theatre. Offering an extensive list of titles, including a preponderance of the most significant American plays of the past half-century, Dramatists Play Service, Inc. -

Dams and Development in China

BRYAN TILT DAMS AND The Moral Economy DEVELOPMENT of Water and Power IN CHINA DAMS AND DEVELOPMENT CHINA IN CONTEMPORARY ASIA IN THE WORLD CONTEMPORARY ASIA IN THE WORLD DAVID C. KANG AND VICTOR D. CHA, EDITORS This series aims to address a gap in the public-policy and scholarly discussion of Asia. It seeks to promote books and studies that are on the cutting edge of their respective disciplines or in the promotion of multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary research but that are also accessible to a wider readership. The editors seek to showcase the best scholarly and public-policy arguments on Asia from any field, including politics, his- tory, economics, and cultural studies. Beyond the Final Score: The Politics of Sport in Asia, Victor D. Cha, 2008 The Power of the Internet in China: Citizen Activism Online, Guobin Yang, 2009 China and India: Prospects for Peace, Jonathan Holslag, 2010 India, Pakistan, and the Bomb: Debating Nuclear Stability in South Asia, Šumit Ganguly and S. Paul Kapur, 2010 Living with the Dragon: How the American Public Views the Rise of China, Benjamin I. Page and Tao Xie, 2010 East Asia Before the West: Five Centuries of Trade and Tribute, David C. Kang, 2010 Harmony and War: Confucian Culture and Chinese Power Politics, Yuan-Kang Wang, 2011 Strong Society, Smart State: The Rise of Public Opinion in China’s Japan Policy, James Reilly, 2012 Asia’s Space Race: National Motivations, Regional Rivalries, and International Risks, James Clay Moltz, 2012 Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations, Zheng Wang, 2012 Green Innovation in China: China’s Wind Power Industry and the Global Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy, Joanna I. -

Utopia/Wutuobang As a Travelling Marker of Time*

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/./), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:./SX UTOPIA/WUTUOBANG AS A TRAVELLING MARKER OF TIME* LORENZO ANDOLFATTO Heidelberg University ABSTRACT. This article argues for the understanding of ‘utopia’ as a cultural marker whose appearance in history is functional to the a posteriori chronologization (or typification) of historical time. I develop this argument via a comparative analysis of utopia between China and Europe. Utopia is a marker of modernity: the coinage of the word wutuobang (‘utopia’) in Chinese around is analogous and complementary to More’s invention of Utopia in ,inthatbothrepresent attempts at the conceptualizations of displaced imaginaries, encounters with radical forms of otherness – the European ‘discovery’ of the ‘New World’ during the Renaissance on the one hand, and early modern China’sown‘Westphalian’ refashioning on the other. In fact, a steady stream of utopian con- jecturing seems to mark the latter: from the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom borne out of the Opium wars, via the utopian tendencies of late Qing fiction in the works of literati such as Li Ruzhen, Biheguan Zhuren, Lu Shi’e, Wu Jianren, Xiaoran Yusheng, and Xu Zhiyan, to the reformer Kang Youwei’s monumental treatise Datong shu. -

Swearing a Cross-Cultural Study in Asian and European Languages

Swearing A cross-cultural study in Asian and European Languages Thesis Submitted to Radboud University Nijmegen For the degree of Master of Arts (M.A) Name: Syahrul Rahman / s4703944 Email: [email protected] Supervisor 1: Dr. Ad Foolen Supervisor 2: Professor Helen de Hoop Master Linguistics Radboud University Nijmegen 2016/2017 0 Acknowledgment In the name of Allah, the beneficent and merciful. All praises be to Allah for His mercy and blessing. He has given me health and strength to complete this master thesis as particular instance of this research. Then, may His peace and blessing be upon to His final prophet and messenger, Muhammad SAW, His family and His best friends. In writing and finishing this thesis, there are many people who have provided their suggestion, motivation, advice and remark that all have helped me to finish this paper. Therefore, I would like to express my big appreciation to all of them. For the first, the greatest thanks to my beloved parents Abd. Rahman and Nuriati and my family who have patiently given their love, moral values, motivation, and even pray for me, in every single prayer just to wish me to be happy, safe and successful, I cannot thank you enough for that. Secondly, I would like to dedicate my special gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Ad Foolen, thanking him for his guidance, assistance, support, friendly talks, and brilliant ideas that all aided in finishing my master thesis. I also wish to dedicate my big thanks to Helen de Hoop, for her kind willingness to be the second reviewer of my thesis. -

Analysi of Dream of the Red Chamber

MULTIPLE AUTHORS DETECTION: A QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF DREAM OF THE RED CHAMBER XIANFENG HU, YANG WANG, AND QIANG WU A bs t r a c t . Inspired by the authorship controversy of Dream of the Red Chamber and the applica- tion of machine learning in the study of literary stylometry, we develop a rigorous new method for the mathematical analysis of authorship by testing for a so-called chrono-divide in writing styles. Our method incorporates some of the latest advances in the study of authorship attribution, par- ticularly techniques from support vector machines. By introducing the notion of relative frequency as a feature ranking metric our method proves to be highly e↵ective and robust. Applying our method to the Cheng-Gao version of Dream of the Red Chamber has led to con- vincing if not irrefutable evidence that the first 80 chapters and the last 40 chapters of the book were written by two di↵erent authors. Furthermore, our analysis has unexpectedly provided strong support to the hypothesis that Chapter 67 was not the work of Cao Xueqin either. We have also tested our method to the other three Great Classical Novels in Chinese. As expected no chrono-divides have been found. This provides further evidence of the robustness of our method. 1. In t r o du c t ion Dream of the Red Chamber (˘¢â) by Cao Xueqin (˘»é) is one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels. For more than one and a half centuries it has been widely acknowledged as the greatest literary masterpiece ever written in the history of Chinese literature. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

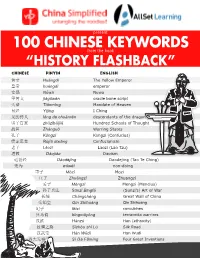

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

The Vagina Monologues by Eve Ensler

The Vagina Monologues by Eve Ensler The official script for the 2008 V-Day Campaigns Available by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc. To order copies of the acting edition of the script of “The Vagina Monologues” (the original – different from the V-Day version of the script) for memento purposes, to sell at your event, or for use in theatre or other classes or workshops, please contact: Customer Service DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC. 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016 Telephone: 212-683-8960, Fax: 212-213-1539 You may also order the acting edition online at www.dramatists.com. Ask for: Book title: The Vagina Monologues ISBN: 0-8222-1772-4 Price: $5.95 Be sure to mention that you represent the V-Day College or Worldwide Campaign. DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC. Representing the American theatre by publishing and licensing the works of new and established playwrights. For more than 65 years Dramatists Play Service, Inc. has provided the finest plays by both established writers and new playwrights of exceptional promise. Formed in 1936 by a number of prominent playwrights and theatre agents, Dramatists Play Service, Inc. was created to foster opportunity and provide support for playwrights by publishing acting editions of their plays and handling the nonprofessional and professional leasing rights to these works. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. has grown steadily to become one of the premier play-licensing agencies in the English speaking theatre. Offering an extensive list of titles, including a preponderance of the most significant American plays of the past half-century, Dramatists Play Service, Inc. -

Disneyization in Shangri-La

Disneyization in Shangri-La Maaike Baks, 1447742 MA Politics, Economy and Society of Asia, supervisor: Prof. dr. S.R. Landsberger Faculty of Humanities, Leiden University 2015 – 2017 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Paradise found 5 Shangri-La, paradise turned theme park? 8 Research Question and Framework 10 The Shangri-La narrative and tourist’s perceptions 11 The postmodernity of Shangri-La and theme parks 11 Authenticity in Shangri-La 12 Western and Chinese tourists’ expectations 14 Chinese theme parks 16 Chinese state and Ethnic minorities 17 Features of a Chinese theme park: Yunnan Ethnic Folk Village 18 Theming 20 Shangri-La themes: the exotic, the sacred and the ethnic 20 Western tourists’ perceptions 22 Hybrid Consumption 25 Merchandising 27 Performative labor 39 Ethnic dancing in Shangri-La and YEFV 30 Conclusion 32 References 34 2 Abstract In 2001, the Chinese government officially recognized Zhongdian County in Yunnan Province as Shangri-La, which is a fictional concept that signifies paradise introduced by the British author James Hilton (1933). Ever since the region has been renamed, some visitors have started to express that Shangri-La County has transformed into a theme park and has lost its authenticity. The current essay explored, by using Bryman’s (2004) theory of Disneyization as a framework, whether it can be said that the name change into Shangri-La has changed the region into a theme park. The resources of this research were scholarly literature, travel blogs and TripAdvisor reviews about Shangri-La. Of the four principles mentioned in Disneyization, that all describe a trend common to a theme park, the principles of theming, hybrid consumption and merchandising were all found to be take place in the Shangri-La region. -

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: a Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: A Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in East Asian Studies April 2014 ©2014 Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Acknowledgements First of all, I thank Professor Ellen Widmer not only for her guidance and encouragement throughout this thesis process, but also for her support throughout my time here at Wellesley. Without her endless patience this study would have not been possible and I am forever grateful to be one of her advisees. I would also like to thank the Wellesley College East Asian Studies Department for giving me the opportunity to take on such a project and for challenging me to expand my horizons each and every day Sincerest thanks to my sisters away from home, Amy, Irene, Cristina, and Beatriz, for the many late night snacks, funny notes, and general reassurance during hard times. I would also like to thank Joe for never losing faith in my abilities and helping me stay motivated. Finally, many thanks to my family and friends back home. Your continued support through all of my endeavors and your ability to endure the seemingly endless thesis rambles has been invaluable to this experience. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1: THE PAIRING OF WOOD AND GOLD Lin Daiyu .................................................................................................