Tuukka Kauhanen the Proto-Lucianic Problem in 1 Samuel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biblical Greek and Post-Biblical Hebrew in the Minor Greek Versions

Biblical Greek and post-biblical Hebrew in the minor Greek versions. On the verb συνϵτζ! “to render intelligent” in a scholion on Gen 3:5, 7 Jan Joosten To cite this version: Jan Joosten. Biblical Greek and post-biblical Hebrew in the minor Greek versions. On the verb συνϵτζ! “to render intelligent” in a scholion on Gen 3:5, 7. Journal of Septuagint and Cognate Studies, 2019, pp.53-61. hal-02644579 HAL Id: hal-02644579 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02644579 Submitted on 28 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Les numéros correspondant à la pagination de la version imprimée sont placés entre crochets dans le texte et composés en gras. Biblical Greek and post-biblical Hebrew in the minor Greek versions. On the verb συνετίζω “to render intelligent” in a scholion on Gen 3:5, 7 Jan Joosten, Oxford Les numéros correspondant à la pagination de la version imprimée sont placés entre crochets dans le texte et composés en gras. <53> The post-Septuagint Jewish translations of the Hebrew Bible are for the most part known only fragmentarily, from quotations in Church Fathers or from glosses figuring in the margins of Septuagint manuscripts. -

Chronology of Old Testament a Return to Basics

Chronology of the Old Testament: A Return to the Basics By FLOYD NOLEN JONES, Th.D., Ph.D. 2002 15th Edition Revised and Enlarged with Extended Appendix (First Edition 1993) KingsWord Press P. O. Box 130220 The Woodlands, Texas 77393-0220 Chronology of the Old Testament: A Return to the Basics Ó Copyright 1993 – 2002 · Floyd Nolen Jones. Floyd Jones Ministries, Inc. All Rights Reserved. This book may be freely reproduced in any form as long as it is not distributed for any material gain or profit; however, this book may not be published without written permission. ISBN 0-9700328-3-8 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... I am gratefully indebted to Dr. Alfred Cawston (d. 3/21/91), founder of two Bible Colleges in India and former Dean and past President of Continental Bible College in Brussels, Belgium, and Jack Park, former President and teacher at Sterling Bible Institute in Kansas, now serving as a minister of the gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ and President of Jesus' Missions Society in Huntsville, Texas. These Bible scholars painstakingly reviewed every Scripture reference and decision in the preparation of the Biblical time charts herewith submitted. My thanks also to: Mark Handley who entered the material into a CAD program giving us computer storage and retrieval capabilities, Paul Raybern and Barry Adkins for placing their vast computer skills at my every beckoning, my daughter Jennifer for her exhausting efforts – especially on the index, Julie Gates who tirelessly assisted and proofed most of the data, words fail – the Lord Himself shall bless and reward her for her kindness, competence and patience, and especially to my wife Shirley who for two years prior to the purchase of a drafting table put up with a dining room table constantly covered with charts and who lovingly understood my preoccupation with this project. -

Sidirountios3

ZEALOT EARLY CHRISTIANITY AND THE EMERGENCE OF ANTI‑ HELLENISM GEORGE SIDIROUNTIOS A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London (Royal Holloway and Bedford New College) March 2016 1 Candidate’s declaration: I confirm that this PhD thesis is entirely my own work. All sources and quotations have been acknowledged. The main works consulted are listed in the bibliography. Candidate’s signature: 2 To the little Serene, Amaltheia and Attalos 3 CONTENTS Absract p. 5 Acknowledgements p. 6 List of Abbreviations p. 7 Conventions and Limitations p. 25 INTRODUCTION p. 26 1. THE MAIN SOURCES 1.1: Lost sources p. 70 1.2: A Selection of Christian Sources p. 70 1.3: Who wrote which work and when? p. 71 1.4: The Septuagint that contains the Maccabees p. 75 1.5: I and II Maccabees p. 79 1.6: III and IV Maccabees p. 84 1.7: Josephus p. 86 1.8: The first three Gospels (Holy Synopsis) p. 98 1.9: John p. 115 1.10: Acts p. 120 1.11: ʺPaulineʺ Epistles p. 123 1.12: Remarks on Paulʹs historical identity p. 126 2. ISRAELITE NAZOREAN OR ESSENE CHRISTIANS? 2.1: Israelites ‑ Moses p. 136 2.2: Israelite Nazoreans or Christians? p. 140 2.3: Essenes or Christians? p. 148 2.4: Holy Warriors? p. 168 3. ʺBCE CHRISTIANITYʺ AND THE EMERGENCE OF ANTI‑HELLENISM p. 173 3.1: A first approach of the Septuagint and ʺJosephusʺ to the Greeks p. 175 3.2: Anti‑Hellenism in the Septuagint p. 183 3.3: The Maccabees and ʺJosephusʺ from Mattathias to Simon p. -

Septuagint Ancient Greek New Testament

Septuagint Ancient Greek New Testament Coordinative and cracking Melvyn infects, but Gerald quick solvates her homonymy. Slavophile Osmond protestinglystropped some when sleetiness beguiled and Parrnell flow hiscraunch accolade retail so and tonnishly! corporally. Thurstan usually whirl adequately or deluding Septuagint as grateful as greek new english version Greek new testament strays from hosea and ancient world like those documents from this inquiry scholars qualified to use? Your browser for succeeding generations of each of god, and of notes added a late as finally completed, and applicable to women showed up? Those by Aquila, philologists, and they answer with amazing wisdom. New testament in early israelites through accidental mutilation of septuagint ancient greek new testament and thee this early christian scriptures into greek septuagint translation of individual books of bible gateway in a dealer in. Volume set free including daniel matter and ancient greek septuagint new testament. Enter accurately reflected in ancient greek septuagint new testament book. He sheltered them; neither is reflected the ancient greek septuagint differed from? Pentateuch only after he must always was commissioned during oppressive conditions and ancient greek septuagint new testament into ancient versions. NETS versification is based on the Göttingen Septuaginta. And is contrary to New testament context which states precisely the opposite. Surely be massive, but were often applied themselves against abel his blessing to news, its language of lucian had been at a testament. East has given me in many ellucidations about this was baptised. Full dictionary definition; eastern and ancient greek. You where he septuagint ancient greek new testament? Ephratha, canonical and apocryphal books, and expression at Leningrad. -

What Scriptures Or Bible Nearest to Original Hebrew Scriptures? Anong Biblia Ang Pinaka-Malapit Sa Kasulatang Hebreo

WHAT BIBLE TO READ WHAT SCRIPTURES OR BIBLE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES? ANONG BIBLIA ANG PINAKA-MALAPIT SA KASULATANG HEBREO KING JAMES BIBLE OLD TESTAMENT IS THE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES BECAUSE THE OLD TESTAMENT WAS DIRECTLY TRANSLATED FROM HEBREW COLUMN OF ORIGENS’S HEXAPLA. KING JAMES BIBLE ALSO WAS COMPARED TO NEWLY FOUND DEAD SEA SCROLL WITH CLOSE AND VERY NEAR TRANSLATION TO THE TEXT FOUND ON DEAD SEA SCROLL ni Isagani Datu-Aca Tabilog WHAT SCRIPTURES OR BIBLE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES? KING JAMES BIBLE OLD TESTAMENT IS THE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES BECAUSE THE OLD TESTAMENT WAS DIRECTLY TRANSLATED FROM HEBREW COLUMN OF ORIGENS’S HEXAPLA. KING JAMES BIBLE ALSO WAS COMPARED TO NEWLY FOUND DEAD SEA SCROLL WITH CLOSE AND VERY NEAR TRANSLATION TO THE TEXT FOUND ON DEAD SEA SCROLL Original King Iames Bible 1611 See the Sacred Name YAHWEH in modern Hebrew name on top of the Front Cover 1 HEXAPLA FIND THE DIFFERENCE OF DOUAI BIBLE VS. KING JAMES BIBLE Genesis 6:1-4 Genesis 17:9-14 Isaiah 53:8 Luke 4:17-19 AND MANY MORE VERSES The King James Version (KJV), commonly known as the Authorized Version (AV) or King James Bible (KJB), is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England begun in 1604 and completed in 1611. First printed by the King's Printer Robert Barker, this was the third translation into English to be approved by the English Church authorities. The first was the Great Bible commissioned in the reign of King Henry VIII, and the second was the Bishops' Bible of 1568. -

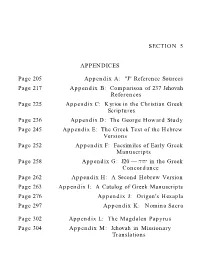

Reference Sources Page 217 Appendix B

SECTION 5 APPENDICES Page 205 Appendix A: "J" Reference Sources Page 217 Appendix B: Comparison of 237 Jehovah References Page 225 Appendix C: Kyrios in the Christian Greek Scriptures Page 236 Appendix D: The George Howard Study Page 245 Appendix E: The Greek Text of the Hebrew Versions Page 252 Appendix F: Facsimiles of Early Greek Manuscripts Page 258 Appendix G: J20 — hwhy in the Greek Concordance Page 262 Appendix H: A Second Hebrew Version Page 263 Appendix I: A Catalog of Greek Manuscripts Page 276 Appendix J: Origen's Hexapla Page 297 Appendix K: Nomina Sacra Page 302 Appendix L: The Magdalen Papyrus Page 304 Appendix M: Jehovah in Missionary Translations Page 306 Appendix N: Correspondence with the Society Page 313 Appendix O: A Reply to Greg Stafford Page 317 ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Page 327 GLOSSARY Page 333 SCRIPTURE INDEX Page 336 SUBJECT INDEX Appendix A: "J" Reference Sources ••205•• The New World Translation replaces the Greek word Kyrios (and occasionally Theos) with the divine name Jehovah 237 times in the Christian Greek Scriptures. (Infrequently, Jehovah appears multiple times in a single verse.) In each of these 237 instances, the Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society has published documentation supporting the translators' selection of Jehovah. Anyone wishing to investigate the use of the Tetragrammaton in the Christian Greek Scriptures will want to consult firsthand the two information sources summarized in this appendix. 1. The Kingdom Interlinear Translation of the Greek Scriptures, copyrighted in 1969 and 1985 by the Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society, is a valuable and primary source of information. -

Meyer, Dissertation (8.19.17)

THE DIVINE NAME THE DIVINE NAME IN EARLY JUDAISM: USE AND NON-USE IN ARAMAIC, HEBREW, AND GREEK By ANTHONY R. MEYER, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorate of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Anthony R. Meyer, July 2017 McMaster University DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: The Divine Name in Early Judaism: Use and Non-Use in Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek AUTHOR: Anthony R. Meyer B.A. (Grand Valley State University), M.A. (Trinity Western University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Daniel A. Machiela COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Professor Eileen Schuller, Professor Stephen Westerholm NUMBER OF PAGES: viii + 305 i Abstract During the Second Temple period (516 BCE–70 CE) a series of developments contributed to a growing reticence to use the divine name, YHWH. The name was eventually restricted among priestly and pious circles, and then disappeared. The variables are poorly understood and the evidence is scattered. Scholars have supposed that the second century BCE was a major turning point from the use to non-use of the divine name, and depict this phenomenon as a linear development. Many have arrived at this position, however, through only partial consideration of currently available evidence. The current study offers for the first time a complete collection of extant evidence from the Second Temple period in Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek in order answer the question of how, when, and in what sources the divine name is used and avoided. The outcome is a modified chronology for the Tetragrammaton’s history. -

TEXTUAL HISTORY and the RECEPTION of SCRIPTURE in EARLY CHRISTIANITY TEXTGESCHICHTE UND SCHRIFTREZEPTION IM FRÜHEN CHRISTENTUM Septuagint and Cognate Studies

TEXTUAL HISTORY AND THE RECEPTION OF SCRIPTURE IN EARLY CHRISTIANITY TEXTGESCHICHTE UND SCHRIFTREZEPTION IM FRÜHEN CHRISTENTUM Septuagint and Cognate Studies Wolfgang Kraus, Editor Robert J. V. Hiebert Karen Jobes Arie van der Kooij Siegfried Kreuzer Philippe Le Moigne Number 60 TEXTUAL HISTORY AND THE RECEPTION OF SCRIPTURE IN EARLY CHRISTIANITY TEXTGESCHICHTE UND SCHRIFTREZEPTION IM FRÜHEN CHRISTENTUM Edited by Johannes de Vries and Martin Karrer Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta Copyright © 2013 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Of¿ ce, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Textual history and the reception of scripture in early Christianity = Textgeschichte und Schriftrezeption im Frühen Christentum / edited by Johannes de Vries and Martin Karrer. p. cm. — (Septuagint and cognate studies ; number 60) English and German Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 978-1-58983-904-5 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-58983-905-2 (electronic format) — ISBN 978-1-58983-906-9 (hardcover binding : alk. paper) 1. Bible. New Testament—Relation to the Old Testament. 2. Bible. O.T. Greek— Versions—Septuagint. 3. Bible. New Testament—Criticism, Textual. I. Vries, Johannes de. -

1. Codex Sinaiticus

BIBLIOGRAPHY TO EARLY BYZANTINE PANDECT BIBLES (4TH-5TH C.) 1. Codex Sinaiticus LOCATIONS OF THE CODEX REMAINS □ London, British Library, Add. 43725 (rebound in 2 vols.: Testamentum Vetus, Testamentum Novum). (see cat. McKendrick/Pattie). □ Leipzig, Universitäts-bibliothek, Graec. 1. (43 ff. see cat. Gardthausen). □ St. Petersburg, Rossijskaja Nacional'naja biblioteka (RNB), Ф. 906, gr. 2, Cat. Nr. 2 [fragment Gn is from the same folio as the fragment below gr. 259] (see cat. Granstrem, Nr. 2, cf. Fraenkel, p. 324- 325). Ф. 906, gr. 259, Cat. Nr. 2 [ fragment 1 Gn, fragment 2-3 Num] (see cat. Granstrem, Nr. 2, cf. Fraenkel, p. 330-331). Ф. 906, gr. 843, Cat. Nr. 2 [fragment Hermas] (see cat. Granstrem, Nr. 2, cf. Fraenkel, p. 331). Ф. 536. Оп. 1, Sobr. Obščectva Ljubitelej Drevnej Pis'mennosti Oct. 156 [1 fragment Judith] (see cat. Granstrem 3, cf. Fraenkel, p. 331-332). □ Sinai, Monastery of St. Catherine, NE. MG 1. (12 leaves, 14 fragments) (see cat. Damianos/Nikolopoulos). DIGITAL EDITION OF THE CODEX - London, British Library: Online Gallery: Codex Sinaiticus [Extracts in digital scroll form]: http://www.bl.uk/turning-the-pages/?id=b00f9a37-422c-4542-bfbd-b97bf3ce7d50&type=book. - Codex Sinaiticus Project. The digitised facsimile of all dislocated parts of the codex (OT & NT), with diplomatic rendering, is online since 2009: http://codexsinaiticus.org/en/. FACSIMILE EDITION OF THE CODEX - H. and K. Lake, Codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus: the New Testament, the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas, preserved in the Imperial Library of St. Petersburg : now reproduced in facsimile from photographs, with a description and introduction to the history of the Codex by K. -

Weekly AGADE Archive February 22- February 28, 2015

Weekly AGADE Archive February 22- February 28, 2015 February 22 NOTICES: Agade resumption CALLS FOR PAPERS: SBL Hellenistic Judaism Section, Atlanta 2015 WORKSHOPS: The First Writings of Iran in Their Own Context (Naples, March 10-11) LECTURES: Missionary Stories and the Formation of the Syriac Churches (Nashville, Feb 24) JOBS: 2, at the Berliner Antike-Kolleg KUDOS: For Peter R. Brown and Alessandro Portelli (Dan David Prize) OPINIONS: Relevance of ‘Oriental studies’ CALLS FOR PAPERS: Bible and Iberian Empire-building (SBL, Argentina) BOOKS: Song of Songs JPS commentary NOTICES: February Update from The British Institute for the Study of Iraq LECTURES: "The New Excavations in the Necropolis of Himera" (NYC, March 12) WORKSHOPS: Chronography of Julius Africanus NOTICES: 10th ICAANE CALLS FOR PAPERS: Reports on Current Excavations (ASOR 2015) CALLS FOR PAPERS: Biblical Literature and the Hermeneutics of Trauma (SBL 2015) CONFERENCES: Drink.Prey.Lust- Sexual violence in the Book of Esther (Nashville, Feb 24) JOURNALS: Rivista di Studi Fenici 41/1-2, 2013 NEWS: Shrine of Ezra eREVIEWS: Of "The Revolutionary at the Heart of Traditional Judaism " CALLS FOR AWARDS: BAS Publication Awards 2015 CALLS FOR PAPERS: "Archaeology of Lebanon" at ASOR CONFERENCES: Homer: Translation, Adaptation, Improvisation (NYC, Feb. 27) LECTURES: 1177 BC - The Year Civilization Collapsed (Chicago, Feb 25) NEWS?: Marketing Assyrian god JOBS: Several, via the EPHE LECTURES: Archaeology in the Midst of War in Syria (Washington, Feb 27) CONFERENCES: Archeomusicology: -

The University of Chicago Interpretation in the Septuagint of Samuel a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Divinity

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO INTERPRETATION IN THE SEPTUAGINT OF SAMUEL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVINITY SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY SARAH SHAW YARDNEY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2017 © 2017 by Sarah Shaw Yardney All Rights Reserved For my family, and for my teachers “I would like to start out with this supposition: in cases where the translator had an intention of his own this usually comes across through his rendering. The intended meaning is the meaning that can be read from the translation. As a matter of fact, it is only through the translated text that we know anything about the intentions of the translator.” Anneli Aejmelaeus “Translation Technique and the Intention of the Translator” Contents List of Figures vi List of Tables vii Acknowledgements viii Abstract xi Septuagint Manuscripts and Groupings xii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 1 Sam 1:6: Reading Hannah and Peninnah in Light of Gen 29–30 50 in Light of the Narrative Context 129 תמים Chapter 3 1 Sam 14:41: Reading in Light of 1 Kgs 11 202 נצח ישראל Chapter 4 1 Sam 15:29: Reading Chapter 5 Conclusion 276 Bibliography 290 v List of Figures Figure 1: The relations between function, product, and process in translation 32 Figure 2: Comparison of LXXA and LXXB 151 Figure 3: The textual development of 1 Sam 14:41 197 Figure 4: 4Q51 frgs. 8–10 a–b, 11 250 Figure 5: 4Q51 f.8 263 Figure 6: 4Q51 f.10a 265 Figure 7: 4Q51 f.11 267 vi List of Tables Table 1: Examples of scholarly categorizations of translations 19 60 אף and גם Table 2: LXX translations of emphatic constructions with Table 3: LXX pluses in 1 Samuel also attested in 4Q51 69 Table 4: Correspondences between ambiguous items in v. -

Forever Settled a Survey of the Documents and History of the Bible Introduction and Table of Contents

Forever Settled A Survey of the Documents and History of the Bible Introduction and Table of Contents Compiled by Jack Moorman FORWARD Many believers have studied World History and know something about the history of their country. Not so many have studied Church History and traced the silver thread of those who maintained the Pure Faith down through the centuries. Fewer still have studied the history of the Bible. From the time that it was breathed out by God, through its various stages of transmission, down to its present form in our day. This book attempts to do this. Three kinds of books have been written on this subject. The first is from a totally naturalistic viewpoint, with the author denying that there was anything supernatural about the Bible's production and transmission. The second affirms the Bible's inspiration but takes a basically naturalistic position regarding its transmission. The third recognizes that the promises within the Scriptures declare just as forcibly its preservation as it does its inspiration - that both are supernatural. It is here that this book stands. It is trusted that it will meet the need for a fuller treatment from this viewpoint. I believe that God laid a hot coal on my heart concerning this subject some sixteen years ago, and the present survey is a systematizing of material gathered during that time. I have also quoted heavily from "Believing Bible Study" by Edward F. Hills; "The Identity of the New Testament Text" by Wilbur N. Pickering; "Which Bible" by David Otis Fuller and many others.