The Feminine As a Metaphor for the New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Metric System: America Measures Up. 1979 Edition. INSTITUTION Naval Education and Training Command, Washington, D.C

DOCONENT RESUME ED 191 707 031 '926 AUTHOR Andersonv.Glen: Gallagher, Paul TITLE The Metric System: America Measures Up. 1979 Edition. INSTITUTION Naval Education and Training Command, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO NAVEDTRA,.475-01-00-79 PUB CATE 1 79 NOTE 101p. .AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing .Office, Washington, DC 2040Z (Stock Number 0507-LP-4.75-0010; No prise quoted). E'DES PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cartoons; Decimal Fractions: Mathematical Concepts; *Mathematic Education: Mathem'atics Instruction,: Mathematics Materials; *Measurement; *Metric System; Postsecondary Education; *Resource Materials; *Science Education; Student Attitudes: *Textbooks; Visual Aids' ABSTRACT This training manual is designed to introduce and assist naval personnel it the conversion from theEnglish system of measurement to the metric system of measurement. The bcokteliswhat the "move to metrics" is all,about, and details why the changeto the metric system is necessary. Individual chaPtersare devoted to how the metric system will affect the average person, how the five basic units of the system work, and additional informationon technical applications of metric measurement. The publication alsocontains conversion tables, a glcssary of metric system terms,andguides proper usage in spelling, punctuation, and pronunciation, of the language of the metric, system. (MP) ************************************.******i**************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made * * from -

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years Ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 Pages This PDF History Timeline Has Been Extracted

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 pages This PDF History Timeline has been extracted from the History World web site's time line. The PDF is a very simplified version of the History World timeline. The PDF is stripped of all the links found on that timeline. If an entry attracts your interest and you want further detail, click on the link at the foot of each of the PDF pages and query the subject or the PDF entry on the web site, or simply do an internet search. When I saw the History World timeline I wanted a copy of it for myself and my family in a form that we could access off-line, on demand, on the device of our choice. This PDF is the result. What attracted me particularly about the History World timeline is that each event, which might be earth shattering in itself with a wealth of detail sufficient to write volumes on, and indeed many such events have had volumes written on them, is presented as a sort of pared down news head-line. Basic unadorned fact. Also, the History World timeline is multi-faceted. Most historic works focus on their own area of interest and ignore seemingly unrelated events, but this timeline offers glimpses of cross-sections of history for any given time, embracing art, politics, war, nations, religions, cultures and science, just to mention a few elements covered. The view is fascinating. Then there is always the question of what should be included and what excluded. -

Metric System Units of Length

Math 0300 METRIC SYSTEM UNITS OF LENGTH Þ To convert units of length in the metric system of measurement The basic unit of length in the metric system is the meter. All units of length in the metric system are derived from the meter. The prefix “centi-“means one hundredth. 1 centimeter=1 one-hundredth of a meter kilo- = 1000 1 kilometer (km) = 1000 meters (m) hecto- = 100 1 hectometer (hm) = 100 m deca- = 10 1 decameter (dam) = 10 m 1 meter (m) = 1 m deci- = 0.1 1 decimeter (dm) = 0.1 m centi- = 0.01 1 centimeter (cm) = 0.01 m milli- = 0.001 1 millimeter (mm) = 0.001 m Conversion between units of length in the metric system involves moving the decimal point to the right or to the left. Listing the units in order from largest to smallest will indicate how many places to move the decimal point and in which direction. Example 1: To convert 4200 cm to meters, write the units in order from largest to smallest. km hm dam m dm cm mm Converting cm to m requires moving 4 2 . 0 0 2 positions to the left. Move the decimal point the same number of places and in the same direction (to the left). So 4200 cm = 42.00 m A metric measurement involving two units is customarily written in terms of one unit. Convert the smaller unit to the larger unit and then add. Example 2: To convert 8 km 32 m to kilometers First convert 32 m to kilometers. km hm dam m dm cm mm Converting m to km requires moving 0 . -

1777 Map of Philadelphia and Parts Adjacent - a Poetose Notebook / Journal / Diary (50 Pages/25 Sheets) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

1777 MAP OF PHILADELPHIA AND PARTS ADJACENT - A POETOSE NOTEBOOK / JOURNAL / DIARY (50 PAGES/25 SHEETS) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Poetose Press | 52 pages | 27 Aug 2019 | Poetose Press | 9781646720361 | English | none 1777 Map of Philadelphia and Parts Adjacent - A Poetose Notebook / Journal / Diary (50 pages/25 sheets) PDF Book In he had a safe-conduct to pass into England or across the sea. Bremen, Kunsthalle. The paintings had been discovered by advancing American troops in wartime storage in the salt mine at Merkers in , had been shipped to the United States aboard the Army transport James Parker in December of that year and stored in the vaults of the National Gallery in Washington. Photograph: Calvin Reinhold seated at his desk painting Frame: 12" x 10". Little did they know how skilled these boys were from playing on an uneven, rock infested dirt court. There are also copies of the obituary of W. This fact was consistent with the four-element theory. Pair of Rococo Revival rosewood parlor chairs, attributed to John Henry Belter , carved in the Rosalie with Grape pattern, laminated shield backs, carved skirt and cabriole legs, mounted with casters. Lucinda Maberry, Mrs. Florence: Centre di Firenze, Information on the charge of common ions can be obtained from the periodic table. Records of the Rev. The records for Emanuel County begin on page 78 and end on page Box 30 ca. Nancy Carmichael, b. Tear lower right margin, approx. A web portfolio is shown via the internet so it can be viewed or downloaded remotely or by anyone with access to the web. -

Forestry Commission Booklet: Forest Mensuration Handbook

Forestry Commission ARCHIVE Forest Mensuration Handbook Forestry Commission Booklet 39 KEY TO PROCEDURES (weight) (weight) page 36 page 36 STANDING TIMBER STANDS SINGLE TREES Procedure 7 page 44 SALE INVENTORY PIECE-WORK THINNING Procedure 8 VALUATION PAYMENT CONTROL page 65 Procedure 9 Procedure 10 Procedure 11 page 81 page 108 page 114 N.B. See page 14 for further details Forestry Commission Booklet No. 39 FOREST MENSURATION HANDBOOK by G. J. Hamilton, m sc FORESTRY COMMISSION London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown copyright 1975 First published 1975 Third impression 1988 ISBN 0 11 710023 4 ODC 5:(021) K eyw ords: Forestry, Mensuration ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The production of the various tables and charts contained in this publication has been very much a team effort by members of the Mensuration Section of the Forestry Commission’s Research & Development Division. J. M. Christie has been largely responsible for initiating and co-ordinating the development and production of the tables and charts. A. C. Miller undertook most of the computer programming required to produce the tables and was responsible for establishing some formheight/top height and tariff number/top height relationships, and for development work in connection with assortment tables and the measurement of stacked timber. R. O. Hendrie prepared the single tree tariff charts and analysed various data concerning timber density, stacked timber, and bark. M. D. Witts established most of the form height/top height and tariff number/top height relationships and investigated bark thickness in the major conifers. Assistance in checking data was given by Miss D. Porchet, Mrs N. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

How Are Units of Measurement Related to One Another?

UNIT 1 Measurement How are Units of Measurement Related to One Another? I often say that when you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meager and unsatisfactory kind... Lord Kelvin (1824-1907), developer of the absolute scale of temperature measurement Engage: Is Your Locker Big Enough for Your Lunch and Your Galoshes? A. Construct a list of ten units of measurement. Explain the numeric relationship among any three of the ten units you have listed. Before Studying this Unit After Studying this Unit Unit 1 Page 1 Copyright © 2012 Montana Partners This project was largely funded by an ESEA, Title II Part B Mathematics and Science Partnership grant through the Montana Office of Public Instruction. High School Chemistry: An Inquiry Approach 1. Use the measuring instrument provided to you by your teacher to measure your locker (or other rectangular three-dimensional object, if assigned) in meters. Table 1: Locker Measurements Measurement (in meters) Uncertainty in Measurement (in meters) Width Height Depth (optional) Area of Locker Door or Volume of Locker Show Your Work! Pool class data as instructed by your teacher. Table 2: Class Data Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 Group 4 Group 5 Group 6 Width Height Depth Area of Locker Door or Volume of Locker Unit 1 Page 2 Copyright © 2012 Montana Partners This project was largely funded by an ESEA, Title II Part B Mathematics and Science Partnership grant through the Montana Office of Public Instruction. -

Measuring in Metric Units BEFORE Now WHY? You Used Metric Units

Measuring in Metric Units BEFORE Now WHY? You used metric units. You’ll measure and estimate So you can estimate the mass using metric units. of a bike, as in Ex. 20. Themetric system is a decimal system of measurement. The metric Word Watch system has units for length, mass, and capacity. metric system, p. 80 Length Themeter (m) is the basic unit of length in the metric system. length: meter, millimeter, centimeter, kilometer, Three other metric units of length are themillimeter (mm) , p. 80 centimeter (cm) , andkilometer (km) . mass: gram, milligram, kilogram, p. 81 You can use the following benchmarks to estimate length. capacity: liter, milliliter, kiloliter, p. 82 1 millimeter 1 centimeter 1 meter thickness of width of a large height of the a dime paper clip back of a chair 1 kilometer combined length of 9 football fields EXAMPLE 1 Using Metric Units of Length Estimate the length of the bandage by imagining paper clips laid next to it. Then measure the bandage with a metric ruler to check your estimate. 1 Estimate using paper clips. About 5 large paper clips fit next to the bandage, so it is about 5 centimeters long. ch O at ut! W 2 Measure using a ruler. A typical metric ruler allows you to measure Each centimeter is divided only to the nearest tenth of into tenths, so the bandage cm 12345 a centimeter. is 4.8 centimeters long. 80 Chapter 2 Decimal Operations Mass Mass is the amount of matter that an object has. The gram (g) is the basic metric unit of mass. -

Villa Savoye Poissy, France [ La Maison Se Posera Au Milieu De L’Herbe Comme Un Objet, Sans Rien Déranger

Villa Savoye Poissy, France [ La maison se posera au milieu de l’herbe comme un objet, sans rien déranger. ] Le Corbusier Villa Savoye Située dans les environs de Paris, et terminée en 1931, la Villa Savoye est une maison de campagne privée conçue par l’architecte d’origine suisse Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, plus connu sous le nom de Le Corbusier. Elle est rapidement devenue l’un des plus célèbres bâtiments dans le style international d’architecture et établit la réputation de Le Corbusier comme l’un des architectes les plus importants du vingtième siècle. Importance architecturale Lorsque la construction de la Villa Savoye commença en 1928, Le Corbusier était déjà un architecte internationalement célèbre. Son livre Vers une Architecture avait été traduit en plusieurs langues, et son travail sur le bâtiment Centrosoyuz à Moscou l’avait mis en contact avec l’avant-garde russe. En tant que l’un des premiers membres du Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), il devenait aussi célèbre comme un défenseur important et éloquent de l’architecture © Fondation Le Corbusier moderne. La Villa Savoye allait être la dernière d’une série de « villas puristes » blanches, conçues et construites par Le Corbusier famille Savoye, Le Corbusier s’est assuré que la conception et son cousin Pierre Jeanneret à Paris et dans les environs de la maison devienne la représentation physique de ses dans les années 1920. Encouragé par la liberté donnée par la idéaux de « pureté totale ». © Fondation Le Corbusier 2 La villa allait être construite en accord avec les « cinq points » emblématiques que Le Corbusier avait développés comme principes directeurs pour son style architectural : 1. -

Villa Savoye Poissy, France [ the House Will Stand in the Midst of the Fields Like an Object, Without Disturbing Anything Around It

Villa Savoye Poissy, France [ The house will stand in the midst of the fields like an object, without disturbing anything around it. ] Le Corbusier Villa Savoye Lying on the outskirts of Paris, France, and completed in 1931, Villa Savoye was designed as a private country house by the Swiss-born architect, Le Corbusier. It quickly became one of the most influential buildings in the International style of architecture and cemented Le Corbusier’s reputation as one of the most important architects of the 20th century. Architectural significance When the construction of Villa Savoye began in 1928, Le Corbusier was already an internationally known architect. His book Vers une Architecture (Towards a New Architecture) had been translated into several languages, while his work on the Centrosoyuz Building in Moscow, Russia, had brought him into contact with the Russian avant-garde. As one of the first members of the Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), he was also becoming known as an important and vocal champion of modern architecture. Villa Savoye would be the last in a series of white ‘Purist villas’ designed and © Fondation Le Corbusier constructed by Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret in and around the city of Paris during the 1920s. Encouraged by the Savoye family’s open brief, Le Corbusier ensured that the design of the house would become the physical representation of his ‘Total Purity’ ideals. © Fondation Le Corbusier 2 The villa was to be constructed according to the emblematic ‘Five Points’ Le Corbusier had developed as guiding principles for his modernist architectural style: 1. -

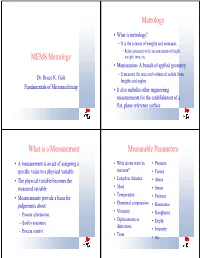

MEMS Metrology Metrology What Is a Measurement Measurable

Metrology • What is metrology? – It is the science of weights and measures • Refers primarily to the measurements of length, MEMS Metrology wetight, time, etc. • Mensuration- A branch of applied geometry – It measure the area and volume of solids from Dr. Bruce K. Gale lengths and angles Fundamentals of Micromachining • It also includes other engineering measurements for the establishment of a flat, plane reference surface What is a Measurement Measurable Parameters • A measurement is an act of assigning a • What do we want to • Pressure specific value to a physical variable measure? • Forces • The physical variable becomes the • Length or distance •Stress measured variable •Mass •Strain • Temperature • Measurements provide a basis for • Friction judgements about • Elemental composition • Resistance •Viscosity – Process information • Roughness • Diplacements or – Quality assurance •Depth distortions – Process control • Intensity •Time •etc. Components of a Measuring Measurement Systems and Tools System • Measurement systems are important tools for the quantification of the physical variable • Measurement systems extend the abilities of the human senses, while they can detect and recognize different degrees of physical variables • For scientific and engineering measurement, the selection of equipment, techniques and interpretation of the measured data are important How Important are Importance of Metrology Measurements? • In human relationships, things must be • Measurement is the language of science counted and measured • It helps us -

Persons Index

Architectural History Vol. 1-46 INDEX OF PERSONS Note: A list of architects and others known to have used Coade stone is included in 28 91-2n.2. Membership of this list is indicated below by [c] following the name and profession. A list of architects working in Leeds between 1800 & 1850 is included in 38 188; these architects are marked by [L]. A table of architects attending meetings in 1834 to establish the Institute of British Architects appears on 39 79: these architects are marked by [I]. A list of honorary & corresponding members of the IBA is given on 39 100-01; these members are marked by [H]. A list of published country-house inventories between 1488 & 1644 is given in 41 24-8; owners, testators &c are marked below with [inv] and are listed separately in the Index of Topics. A Aalto, Alvar (architect), 39 189, 192; Turku, Turun Sanomat, 39 126 Abadie, Paul (architect & vandal), 46 195, 224n.64; Angoulême, cath. (rest.), 46 223nn.61-2, Hôtel de Ville, 46 223n.61-2, St Pierre (rest.), 46 224n.63; Cahors cath (rest.), 46 224n.63; Périgueux, St Front (rest.), 46 192, 198, 224n.64 Abbey, Edwin (painter), 34 208 Abbott, John I (stuccoist), 41 49 Abbott, John II (stuccoist): ‘The Sources of John Abbott’s Pattern Book’ (Bath), 41 49-66* Abdallah, Emir of Transjordan, 43 289 Abell, Thornton (architect), 33 173 Abercorn, 8th Earl of (of Duddingston), 29 181; Lady (of Cavendish Sq, London), 37 72 Abercrombie, Sir Patrick (town planner & teacher), 24 104-5, 30 156, 34 209, 46 284, 286-8; professor of town planning, Univ.