Final Project Report (To Be Submitted by 30Th September 2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

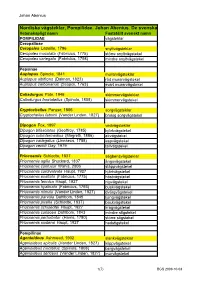

Nordiska Vägsteklar, Pompilidae. Johan Abenius. De Svenska

Johan Abenius Nordiska vägsteklar, Pompilidae. Johan Abenius. De svenska namnen fastställda av Kommittén för svenska djurnamn 100825 Vetenskapligt namn Fastställt svenskt namn POMPILIDAE vägsteklar Ceropalinae Ceropales Latreille, 1796 snyltvägsteklar Ceropales maculata (Fabricius, 1775) större snyltvägstekel Ceropales variegata (Fabricius, 1798) mindre snyltvägstekel Pepsinae Auplopus Spinola, 1841 murarvägsteklar Auplopus albifrons (Dalman, 1823) röd murarvägstekel Auplopus carbonarius (Scopoli, 1763) svart murarvägstekel Caliadurgus Pate, 1946 skimmervägsteklar Caliadurgus fasciatellus (Spinola, 1808) skimmervägstekel Cryptocheilus Panzer, 1806 sorgvägsteklar Cryptocheilus fabricii (Vander Linden, 1827) brokig sorgvägstekel Dipogon Fox, 1897 vedvägsteklar Dipogon bifasciatus (Geoffroy, 1785) björkvägstekel Dipogon subintermedius (Magretti, 1886) ekvägstekel Dipogon variegatus (Linnaeus, 1758) aspvägstekel Dipogon vechti Day, 1979 tallvägstekel Priocnemis Schiødte, 1837 sågbensvägsteklar Priocnemis agilis Shuckard, 1837 ängsvägstekel Priocnemis confusor Wahis, 2006 stäppvägstekel Priocnemis cordivalvata Haupt, 1927 hjärtvägstekel Priocnemis exaltata (Fabricius, 1775) höstvägstekel Priocnemis fennica Haupt, 1927 nipvägstekel Priocnemis hyalinata (Fabricius, 1793) buskvägstekel Priocnemis minuta (Vander Linden, 1827) dvärgvägstekel Priocnemis parvula Dahlbom, 1845 ljungvägstekel Priocnemis pusilla (Schiødte, 1837) backvägstekel Priocnemis schioedtei Haupt, 1927 kragvägstekel Priocnemis coriacea Dahlbom, 1843 mindre stigstekel Priocnemis -

Millichope Park and Estate Invertebrate Survey 2020

Millichope Park and Estate Invertebrate survey 2020 (Coleoptera, Diptera and Aculeate Hymenoptera) Nigel Jones & Dr. Caroline Uff Shropshire Entomology Services CONTENTS Summary 3 Introduction ……………………………………………………….. 3 Methodology …………………………………………………….. 4 Results ………………………………………………………………. 5 Coleoptera – Beeetles 5 Method ……………………………………………………………. 6 Results ……………………………………………………………. 6 Analysis of saproxylic Coleoptera ……………………. 7 Conclusion ………………………………………………………. 8 Diptera and aculeate Hymenoptera – true flies, bees, wasps ants 8 Diptera 8 Method …………………………………………………………… 9 Results ……………………………………………………………. 9 Aculeate Hymenoptera 9 Method …………………………………………………………… 9 Results …………………………………………………………….. 9 Analysis of Diptera and aculeate Hymenoptera … 10 Conclusion Diptera and aculeate Hymenoptera .. 11 Other species ……………………………………………………. 12 Wetland fauna ………………………………………………….. 12 Table 2 Key Coleoptera species ………………………… 13 Table 3 Key Diptera species ……………………………… 18 Table 4 Key aculeate Hymenoptera species ……… 21 Bibliography and references 22 Appendix 1 Conservation designations …………….. 24 Appendix 2 ………………………………………………………… 25 2 SUMMARY During 2020, 811 invertebrate species (mainly beetles, true-flies, bees, wasps and ants) were recorded from Millichope Park and a small area of adjoining arable estate. The park’s saproxylic beetle fauna, associated with dead wood and veteran trees, can be considered as nationally important. True flies associated with decaying wood add further significant species to the site’s saproxylic fauna. There is also a strong -

Final Report 1

Sand pit for Biodiversity at Cep II quarry Researcher: Klára Řehounková Research group: Petr Bogusch, David Boukal, Milan Boukal, Lukáš Čížek, František Grycz, Petr Hesoun, Kamila Lencová, Anna Lepšová, Jan Máca, Pavel Marhoul, Klára Řehounková, Jiří Řehounek, Lenka Schmidtmayerová, Robert Tropek Březen – září 2012 Abstract We compared the effect of restoration status (technical reclamation, spontaneous succession, disturbed succession) on the communities of vascular plants and assemblages of arthropods in CEP II sand pit (T řebo ňsko region, SW part of the Czech Republic) to evaluate their biodiversity and conservation potential. We also studied the experimental restoration of psammophytic grasslands to compare the impact of two near-natural restoration methods (spontaneous and assisted succession) to establishment of target species. The sand pit comprises stages of 2 to 30 years since site abandonment with moisture gradient from wet to dry habitats. In all studied groups, i.e. vascular pants and arthropods, open spontaneously revegetated sites continuously disturbed by intensive recreation activities hosted the largest proportion of target and endangered species which occurred less in the more closed spontaneously revegetated sites and which were nearly absent in technically reclaimed sites. Out results provide clear evidence that the mosaics of spontaneously established forests habitats and open sand habitats are the most valuable stands from the conservation point of view. It has been documented that no expensive technical reclamations are needed to restore post-mining sites which can serve as secondary habitats for many endangered and declining species. The experimental restoration of rare and endangered plant communities seems to be efficient and promising method for a future large-scale restoration projects in abandoned sand pits. -

Brood Parasitism in a Host Generalist, the Shiny Cowbird: I

BROOD PARASITISM IN A HOST GENERALIST, THE SHINY COWBIRD: I. THE QUALITY OF DIFFERENT SPECIES AS HOSTS PAUL MASON 1 Departmentof Zoology,University of Texas,Austin, Texas 78712 USA ASSTRACT.--TheShiny Cowbird (Molothrusbonariensis) of South America, Panama, and the West Indies is an obligate brood parasiteknown to have used 176 speciesof birds as hosts. This study documentswide variability in the quality of real and potential hostsin terms of responseto eggs, nestling diet, and nest survivorship. The eggs of the parasiteare either spotted or immaculate in eastern Argentina and neighboring parts of Uruguay and Brazil. Most speciesaccept both morphs of cowbird eggs,two reject both morphs, and one (Chalk- browed Mockingbird, Mimus saturninus)rejects immaculate eggs but acceptsspotted ones. No species,via its rejection behavior, protectsthe Shiny Cowbird from competition with a potentialcompetitor, the sympatricScreaming Cowbird (M. rufoaxillaris).Cross-fostering ex- periments and natural-history observationsindicate that nestling cowbirds require a diet composedof animal protein. Becausemost passerinesprovide their nestlingswith suchfood, host selectionis little restricted by diet. Species-specificnest survivorship, adjustedto ap- propriatevalues of Shiny Cowbird life-history variables,varied by over an order of mag- nitude. Shiny Cowbirds peck host eggs.This density-dependentsource of mortality lowers the survivorshipof nestsof preferred hostsand createsnatural selectionfor greater gener- alization. Host quality is sensitive to the natural-history attributes of each host speciesand to the behavior of cowbirds at nests.Received 4 June1984, accepted26 June1985. VARIATIONin resourcequality can have great parasitized176 species(Friedmann et al. 1977). ecologicaland evolutionary consequences.Ob- The Shiny Cowbird is sympatric with a poten- ligate brood parasites never build nests but tial competitor, the ScreamingCowbird (M. -

Rejection Behavior by Common Cuckoo Hosts Towards Artificial Brood Parasite Eggs

REJECTION BEHAVIOR BY COMMON CUCKOO HOSTS TOWARDS ARTIFICIAL BROOD PARASITE EGGS ARNE MOKSNES, EIVIN ROSKAFT, AND ANDERS T. BRAA Departmentof Zoology,University of Trondheim,N-7055 Dragvoll,Norway ABSTRACT.--Westudied the rejectionbehavior shown by differentNorwegian cuckoo hosts towardsartificial CommonCuckoo (Cuculus canorus) eggs. The hostswith the largestbills were graspejectors, those with medium-sizedbills were mostlypuncture ejectors, while those with the smallestbills generally desertedtheir nestswhen parasitizedexperimentally with an artificial egg. There were a few exceptionsto this general rule. Becausethe Common Cuckooand Brown-headedCowbird (Molothrus ater) lay eggsthat aresimilar in shape,volume, and eggshellthickness, and they parasitizenests of similarly sizedhost species,we support the punctureresistance hypothesis proposed to explain the adaptivevalue (or evolution)of strengthin cowbirdeggs. The primary assumptionand predictionof this hypothesisare that somehosts have bills too small to graspparasitic eggs and thereforemust puncture-eject them,and that smallerhosts do notadopt ejection behavior because of the heavycost involved in puncture-ejectingthe thick-shelledparasitic egg. We comparedour resultswith thosefor North AmericanBrown-headed Cowbird hosts and we found a significantlyhigher propor- tion of rejectersamong CommonCuckoo hosts with graspindices (i.e. bill length x bill breadth)of <200 mm2. Cuckoo hosts ejected parasitic eggs rather than acceptthem as cowbird hostsdid. Amongthe CommonCuckoo hosts, the costof acceptinga parasiticegg probably alwaysexceeds that of rejectionbecause cuckoo nestlings typically eject all hosteggs or nestlingsshortly after they hatch.Received 25 February1990, accepted 23 October1990. THEEGGS of many brood parasiteshave thick- nestseither by grasping the eggs or by punc- er shells than the eggs of other bird speciesof turing the eggs before removal. Rohwer and similar size (Lack 1968,Spaw and Rohwer 1987). -

Bees and Wasps of the East Sussex South Downs

A SURVEY OF THE BEES AND WASPS OF FIFTEEN CHALK GRASSLAND AND CHALK HEATH SITES WITHIN THE EAST SUSSEX SOUTH DOWNS Steven Falk, 2011 A SURVEY OF THE BEES AND WASPS OF FIFTEEN CHALK GRASSLAND AND CHALK HEATH SITES WITHIN THE EAST SUSSEX SOUTH DOWNS Steven Falk, 2011 Abstract For six years between 2003 and 2008, over 100 site visits were made to fifteen chalk grassland and chalk heath sites within the South Downs of Vice-county 14 (East Sussex). This produced a list of 227 bee and wasp species and revealed the comparative frequency of different species, the comparative richness of different sites and provided a basic insight into how many of the species interact with the South Downs at a site and landscape level. The study revealed that, in addition to the character of the semi-natural grasslands present, the bee and wasp fauna is also influenced by the more intensively-managed agricultural landscapes of the Downs, with many species taking advantage of blossoming hedge shrubs, flowery fallow fields, flowery arable field margins, flowering crops such as Rape, plus plants such as buttercups, thistles and dandelions within relatively improved pasture. Some very rare species were encountered, notably the bee Halictus eurygnathus Blüthgen which had not been seen in Britain since 1946. This was eventually recorded at seven sites and was associated with an abundance of Greater Knapweed. The very rare bees Anthophora retusa (Linnaeus) and Andrena niveata Friese were also observed foraging on several dates during their flight periods, providing a better insight into their ecology and conservation requirements. -

Journal of Threatened Taxa

ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Journal of Threatened Taxa 15 February 2019 (Online & Print) Vol. 11 | No. 2 | 13195–13250 PLATINUM 10.11609/jott.2019.11.2.13195-13250 OPEN www.threatenedtaxa.org ACCESS Building evidence for conservation globally MONOGRAPH J TT ISSN 0974-7907 (Online); ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Publisher Host Wildlife Information Liaison Development Society Zoo Outreach Organization www.wild.zooreach.org www.zooreach.org No. 12, Thiruvannamalai Nagar, Saravanampatti - Kalapatti Road, Saravanampatti, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Ph: +91 9385339863 | www.threatenedtaxa.org Email: [email protected] EDITORS Typesetting Founder & Chief Editor Mr. Arul Jagadish, ZOO, Coimbatore, India Dr. Sanjay Molur Mrs. Radhika, ZOO, Coimbatore, India Wildlife Information Liaison Development (WILD) Society & Zoo Outreach Organization (ZOO), Mrs. Geetha, ZOO, Coimbatore India 12 Thiruvannamalai Nagar, Saravanampatti, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Mr. Ravindran, ZOO, Coimbatore India Deputy Chief Editor Fundraising/Communications Dr. Neelesh Dahanukar Mrs. Payal B. Molur, Coimbatore, India Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Pune, Maharashtra, India Editors/Reviewers Managing Editor Subject Editors 2016-2018 Mr. B. Ravichandran, WILD, Coimbatore, India Fungi Associate Editors Dr. B.A. Daniel, ZOO, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Dr. B. Shivaraju, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India Ms. Priyanka Iyer, ZOO, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Prof. Richard Kiprono Mibey, Vice Chancellor, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya Dr. Mandar Paingankar, Department of Zoology, Government Science College Gadchiroli, Dr. R.K. Verma, Tropical Forest Research Institute, Jabalpur, India Chamorshi Road, Gadchiroli, Maharashtra 442605, India Dr. V.B. Hosagoudar, Bilagi, Bagalkot, India Dr. Ulrike Streicher, Wildlife Veterinarian, Eugene, Oregon, USA Dr. -

Hymenoptera Aculeata: Pompilidae) 93-106 DROSERA 2001: 93-10 6 Oldenburg 2001

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Drosera Jahr/Year: 2001 Band/Volume: 2001 Autor(en)/Author(s): Bleidorn Christoph, Lauterbach Karl-Ernst, Venne Christian Artikel/Article: Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Wegwespenfauna Westfalens (Hymenoptera Aculeata: Pompilidae) 93-106 DROSERA 2001: 93-10 6 Oldenburg 2001 Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Wegwespenfauna Westfalens (Hymenoptera Aculeata: Pompilidae) Christoph Bleidorn, Karl-Ernst Lauterbach & Christian Venne Abstract: This paper gives a supplement to the known fauna of Westphalian spider-wasps (Northrhine-Westphalia, Germany). 30 out of 44 known species have been found in the area under investigation including numerous rare and endangered species. Remarkable for the fauna of Northwest-Germany are the records of Aporus unicolor, Arachnospila wesmaeli, Ceropales maculata, Cryptocheilus notatus, Episyron albonotatum, and Evagetes gibbulus. Remarks on the biology, phenology, abundance, and endangerment of the species are gi - ven. Our data together with data from the literature are compiled in a checklist for the spi - der wasps of Westphalia. The results emphasize the importance of the primary and secon - dary sand habitats for the Westphalian spider-wasps. 1. Einleitung Die Wegwespen (Pompilidae) sind weltweit mit über 4200 beschriebenen Arten kosmo - politisch verbreitet ( BROTHERS & F INNAMORE 1993). Ihre Stellung innerhalb des Phyloge - netischen Systems der aculeaten Hymenopteren ist noch umstritten. Die Aculeata im weiteren Sinne werden in 3 monophyletische Teilgruppen gegliedert: Die Chrysidoidea (ein Taxon das die Goldwespen (Chrysididae) und ihre Verwandten umfasst), Apoidea (Grabwespen („Sphecidae“) und Bienen (Apidae), wobei letztere als Teilgruppe der Grabwespen angesehen werden können (siehe z. B. OHL 1995)), und Vespoidea (alle restlichen Aculeaten). -

Sphecidae" (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae & Crabronidae) from Sicily (Italy) and Malta

Linzer biol. Beitr. 35/2 747-762 19.12.2003 New records of "Sphecidae" (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae & Crabronidae) from Sicily (Italy) and Malta C. SCHMID-EGGER Abstract: Two large samples from Sicily and Malta are revised. They include 126 species from Sicily, 19 species of them are new for the fauna of Sicily: Astata gallica, Belomicrus italicus, Crabro peltarius bilbaoensis, Crossocerus podagricus, Gorytes procrustes, Lindenius albilabris, Lindenius laevis, Passaloecus pictus, Pemphredon austrica, Pemphredon lugubris, Rhopalum clavipes, Spilomena troglodytes, Stigmus solskyi, Synnevrus decemmaculatus, Tachysphex julliani, Trypoxylon kolazyi, Trypoxylon medium. Miscophus mavromoustakisi, found in Sicily, is also new for the fauna of Italy. A species of the genus Synnevrus is probably unknown to science. The total number of species in Sicily is 217 now. Zoogeographical aspects are discussed. Most of the recorded species are by origin from central or southern Europe. A few species have an eastern, resp. western Mediterranean distribution pattern. A species is a northern African element. Key words: Hymenoptera, Apoidea, Sphecidae, Crabronidae, Sicily, Italy, Malta, fauna, zoogeographical aspects, endemism. Introduction The fauna of Sphecidae from Sicily was never treated in a special publication. PAGLIANO (1990), in his catalogue of the Sphecidae from Italy, was the first who listed all published records of Sphecidae from Sicily. NEGRISOLO (1995) completed the listing in the ‘Checklist della specie della fauna Italiana’. He listed 186 species names, and some subspecies names from Sicily. Nevertheless, the fauna of Sicily is far from being completely known. I had the opportunity to examine two large collections from Sicily. Bernhard Merz collected in June 1999 Diptera at Sicily and Malta and took also many Aculeate with him. -

Frontiers in Zoology

Frontiers in Zoology This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon. A cuckoo in wolves' clothing? Chemical mimicry in a specialized cuckoo wasp of the European beewolf (Hymenoptera, Chrysididae and Crabronidae) Frontiers in Zoology 2008, 5:2 doi:10.1186/1742-9994-5-2 Erhard Strohm ([email protected]) Johannes Kroiss ([email protected]) Gudrun Herzner ([email protected]) Claudia Laurien-Kehnen ([email protected]) Wilhelm Boland ([email protected]) Peter Schreier ([email protected]) Thomas Schmitt ([email protected]) ISSN 1742-9994 Article type Research Submission date 30 May 2007 Acceptance date 11 January 2008 Publication date 11 January 2008 Article URL http://www.frontiersinzoology.com/content/5/1/2 This peer-reviewed article was published immediately upon acceptance. It can be downloaded, printed and distributed freely for any purposes (see copyright notice below). Articles in Frontiers in Zoology are listed in PubMed and archived at PubMed Central. For information about publishing your research in Frontiers in Zoology or any BioMed Central journal, go to http://www.frontiersinzoology.com/info/instructions/ For information about other BioMed Central publications go to http://www.biomedcentral.com/ © 2008 Strohm et al., licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Un Gynandromorphe D'anoplius Viaticus (LINNAEUS) Et

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 28/1 547-551 20.8.1996 Un gynandromorphe d'Anoplius viaticus (LINNAEUS) et deux cas de monstruosite chez Priocnemis minuta (VANDER LINDEN) et Priocnemis susterai HAUPT (Hymenoptera, Pompilidae) R. WAMS Abstract: Description of gynandromorphic specimen of Anoplius viaticus (L.) and two genetical anomaly: defective specimen of Priocnemis minuta (VANDER LINDEN) 9 and Priocnemis susterai HAUPT 6 . Dicyrtomellus nilssoni WOLF 1990 9 is a junior synonym of Pompilus simulans PRIESNER, 1955 syn. nov. with distorted propodeum (= Dicyrtomellus simulans comb, nov.). Mr Nico-Schneider, entomologiste luxembourgeois bien connu pour ses recherches sur la faune locale, m'a recemment soumis pour verification d'identite ou determina- tion un lot de plus de 150 pompilides du Grand-Duche de Luxembourg, captures de 1992 ä 1995 dans le cadre d'une etude de la faune des carrieres abandonnees. J'y trouvai notamment un exemplaire d'Anoplius viaticus L. pris ä Dodelange le 4 viii.1995 sur une inflorescence de Daucus carota L. par Mr Josy Cungs et identifie comme 9, ce qui ä premiere vue paraissait correct. Un examen plus attentif devait cependant me permettre de constater que la tete, y compris les antennes de 13 ar- ticles, etait bien celle d'un 6 alors que tout le reste du corps: thorax, gastre, pattes et ailes etaient du sexe 9. Ce phenomene genetique, bien connu, reste cependant relativement rare et malgre le nombre considerable de pompilides qui me sont passes par les mains sur pres d'un demi-siecle, c'est la premiere fois que j'observe le cas chez une espece europeenne. -

Eucera, Beiträge Zur Apidologie

Eucera Beiträge zur Apidologie Nr. 10 ISSN 1866-1521 25. November 2016 Eucera 10, 2016 Inhaltsverzeichnis Paul Westrich: Zum Pollensammelverhalten der auf Kreuzblütler spezialisierten Bienenarten Andrena ranunculorum und Andrena probata (Hymenoptera, Apidae) .................................................................................. 3 Paul Westrich & Josef Bülles: Epeolus fallax, ein Brutparasit von Colletes hederae und eine für Deutschland neue Bienenart (Hymenoptera, Apidae) ........................................................................................................................ 15 Paul Westrich: Die Sandbiene Andrena fulva (Hymenoptera, Apidae) als Pollensammler am Pfaffenhütchen (Euonymus europaeus) .......................................................................................................................................................... 27 Content Paul Westrich: Pollen collecting behaviour of two bee species specialized on Brassicaceae: Andrena ranun- culorum und Andrena probata (Hymenoptera, Apidae) ............................................................................................. 3 Paul Westrich & Josef Bülles: Epeolus fallax, a broodparasite of Colletes hederae and a new species for the bee fauna of Germany (Hymenoptera, Apidae) ............................................................................................ 15 Paul Westrich: Andrena fulva collects pollen from spindle (Euonymus europaeus) ......................................... 27 Anmerkung des Herausgebers Seit März