Handbookforcanada1930.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History and Legacy of Yokahú 506 Lodge

Order of the Arrow Yokahú Lodge 506 Puerto Rico Council 661 The History and Legacy of Yokahú 506 Lodge Compiled and edited by: Carlos E. Calzada Preston Page | 1 Acknowledgments and Dedication History is an ever-expanding field that grows with every passing event and action. I thank all those who have helped me in the creation of the Yokahú 506 History Book. I particularly want to thank and acknowledge the effort and support that Mr. Luis Machuca has given me, through his counseling, encouragement and sharing the personal information he has recollected throughout his life. Moreover, Mr. Luis Machuca not only allowed transcript information from his book “La Filosofía del Escutismo y su Presencia en Puerto Rico 1910-2010”, he personally translated the text related to the Order of the Arrow. I would also like to extend my appreciation to Mr. Carlos Acevedo and Mr. Carlos “Pucho” Gandía, who allowed use of personal photographs, documents and provided additional insight through his many anecdotes. Finally, I would like to thank my father, Enrique Calzada, for all the support and help he has given me. I couldn’t have done this without you. It is through the actions of those who work to preserve and educate others about the past that we can move without hesitation into the future. Thus, I dedicate this compilation of historical facts to Mr. Luis Machuca and all those who, throughout the years, have dedicated themselves passionately to researching and preserving our Lodge’s rich history. To all of you, an eternal Thank You! from all of us who can now enjoy reading and learning from your works. -

40Th Anniversary Beaver Scouts Booklet

Happy 40th Birthday Beaver Scouts 1974 – 2014 A booklet celebrating 40 years of Beaver Scouts in Canada — full of ideas for Beaver Scouts and their Scouters. TABLE OF CONTENTS Beaver Scouts 40th Anniversary Celebration Themes .....................2 Lord Robert & Lady Olave Baden-Powell ...............................3 Where Beaver Scouts Began! .........................................3 Some of Baden-Powell’s Favourite Activities! ...........................5 Exploring 40 .......................................................8 Saying Hello in 40 ways ............................................10 40 Years of Beaver Scouting – What’s happened in 40 years! ..............11 Games of the 70’s, 80’s, 90’s & 00’s .................................13 Cartoons of the 70’s, 80’s, 90’s & 00’s ................................13 Inventions of the 70’s, 80’s, 90’s & 00’s ...............................14 Music of the 70’s, 80’s, 90’s & 00’s ...................................14 New Foods of the 70’s, 80’s, 90’s & 00’s .............................. 15 Around the World ..................................................16 What do you imagine Beavers will do at their meetings 100 years from now? ..21 Do you think that 100 years from now Beavers, Cubs, Scouts, Venturers and Rovers will be doing the same?. 22 Thank you, Lord Baden-Powell, for the gift of Scouting! .................23 40th Birthday Campfire .............................................24 40th Birthday Beaver Scouts’ Own ....................................25 Songs, Skits and Cheers .............................................28 -

CHICAS: Discovering Hispanic Heritage Patch Program

CHICAS: Discovering Hispanic Heritage Patch Program This patch program is designed to help Girl Scouts of all cultures develop an understanding and appreciation of the culture of Hispanic / Latin Americans through Discover, Connect and Take Action. ¡Bienvenidos! Thanks for your interest in the CHICAS: Discovering Hispanic Heritage Patch Program. You do not need to be an expert or have any previous knowledge on the Hispanic / Latino Culture in order to teach your girls about it. All of the activities include easy-to-follow activity plans complete with discussion guides and lists for needed supplies. The Resource Guide located on page 6 can provide some valuable support and additional information. 1 CHICAS: Discovering Hispanic Heritage Patch Program Requirements Required Activity for ALL levels: Choose a Spanish speaking country and make a brochure or display about the people, culture, land, costumes, traditions, etc. This activity may be done first or as a culminating project. Girl Scout Daisies: Choose one activity from DISCOVER, one from CONNECT and one from TAKE ACTION for a total of FOUR activities. Girl Scout Brownies: Choose one activity from DISCOVER, one from CONNECT and one from TAKE ACTION. Complete one activity from any category for a total of FIVE activities. Girl Scout Juniors: Choose one activity from DISCOVER, one from CONNECT and one from TAKE ACTION. Complete two activities from any category for a total of SIX activities. Girl Scout Cadettes, Seniors and Ambassadors: Choose two activities from DISCOVER, two from CONNECT and two from TAKE ACTION. Then, complete the REFLECTION activity, for a total of SEVEN activities. -

FROM BULLDOGS to SUN DEVILS the EARLY YEARS ASU BASEBALL 1907-1958 Year ...Record

THE TRADITION CONTINUES ASUBASEBALL 2005 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 2 There comes a time in a little boy’s life when baseball is introduced to him. Thus begins the long journey for those meant to play the game at a higher level, for those who love the game so much they strive to be a part of its history. Sun Devil Baseball! NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONS: 1965, 1967, 1969, 1977, 1981 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 3 ASU AND THE GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD > For the past 26 years, USA Baseball has honored the top amateur baseball player in the country with the Golden Spikes Award. (See winners box.) The award is presented each year to the player who exhibits exceptional athletic ability and exemplary sportsmanship. Past winners of this prestigious award include current Major League Baseball stars J. D. Drew, Pat Burrell, Jason Varitek, Jason Jennings and Mark Prior. > Arizona State’s Bob Horner won the inaugural award in 1978 after hitting .412 with 20 doubles and 25 RBI. Oddibe McDowell (1984) and Mike Kelly (1991) also won the award. > Dustin Pedroia was named one of five finalists for the 2004 Golden Spikes Award. He became the seventh all-time final- ist from ASU, including Horner (1978), McDowell (1984), Kelly (1990), Kelly (1991), Paul Lo Duca (1993) and Jacob Cruz (1994). ODDIBE MCDOWELL > With three Golden Spikes winners, ASU ranks tied for first with Florida State and Cal State Fullerton as the schools with the most players to have earned college baseball’s top honor. BOB HORNER GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD WINNERS 2004 Jered Weaver Long Beach State 2003 Rickie Weeks Southern 2002 Khalil Greene Clemson 2001 Mark Prior Southern California 2000 Kip Bouknight South Carolina 1999 Jason Jennings Baylor 1998 Pat Burrell Miami 1997 J.D. -

"Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition Samuel O

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Indiana University Bloomington Maurer School of Law Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 2 Fall 2000 "Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition Samuel O. Regalado California State University, Stanislaus Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Regalado, Samuel O. (2000) ""Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition," Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol8/iss1/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition SAMUEL 0. REGALADO ° INTRODUCTION "Bonuses? Big money promises? Uh-uh. Cambria's carrot was the fame and glory that would come from playing bisbol in the big leagues," wrote Ray Fitzgerald, reflecting on Washington Senators scout Joe Cambria's tactics in recruiting Latino baseball talent from the mid-1930s through the 1950s.' Cambria was the first of many scouts who searched Latin America for inexpensive recruits for their respective ball clubs. -

Spirituality in the Scouts Canada Program a Proposal – December 2011

Spirituality in the Scouts Canada Program a proposal – December 2011 Lord Baden-Powell & Duty to God God is not some narrow-minded personage, as some people would seem to imagine, but a vast Spirit of Love that overlooks the minor differences of form and creed and denomination and which blesses every [person] who really tries to do his [/her] best, according to his [/her] lights, in His service. in “Rovering to Success” Reverence to God, reverence for one’s neighbour and reverence for oneself as a servant of God, are the basis of every form of religion. in “Aids to Scoutmastership” Spirituality means guiding ones’ own canoe through the torrent of events and experiences of one’s own history and of that of [humankind]. To neglect to hike – that is, to travel adventurously – is to neglect a duty to God. God has given us individual bodies, minds and soul to be developed in a world full of beauties and wonders. in “The Scouter” January 1932 The aim in Nature study is to develop a realisation of God the Creator, and to infuse a sense of the beauty of Nature. in “Girl Guiding” Real Nature study means…knowing about everything that is not made by [humans], but is created by God. In all of this, it is the spirit that matters. Our Scout law and Promise, when we really put them into practice, take away all occasion for wars and strife among nations. The wonder to me of all wonders is how some teachers have neglected Nature study, this easy and unfailing means of education, and have struggled to impose Biblical instruction as the first step towards getting a restless, full-spirited boy to think of higher things. -

Busy Beavers (White Tails) 4 Keeo 4 Guidelines for Linking Beavers to Cubs WHY TAILS?

Cha pter 7 TAIL GROUPS AND LODGES Why Tails? 4 Purpose of Tails 4 Tail Colours 4 Determination of Tail Colour 4 Program Use of Tails 4 Benefits of Lodges 4 Choosing a Lodge Patch 4 Activity Ideas for Tails and Lodges 4 Busy Beavers (White Tails) 4 Keeo 4 Guidelines for Linking Beavers to Cubs WHY TAILS? “I like to wear my Beaver tail because it makes me look like a real beaver.” You’ll hear these words from many Beavers. The Beaver tail is important to them because it’s part of their mag - ical world, and they identify very closely with real beavers. Beaver tails symbolize the stages of development different age groups are going through. They’re concrete recognition that the children are growing bigger physically and developing socially and emotionally. Chapter 6 talks about understanding and working with Beavers. It also looks at characteristics and abilities of children in the Beaver age group, and suggests leaders take them into consid - eration when building programs. Tail groups are designed to help you do this effectively. PURPOSE OF TAILS Beaver tails have a special purpose. They are meant to celebrate personal change and growth in children at their specific age. Goals include, to: 4 Provide a means to build Beavers’ self-esteem by positive recognition of personal growth and development. 4 Provide Beavers with the opportunity to interact with peers who are at a similar stage of development. 4 Help leaders plan programs by grouping Beavers of similar abilities and levels of understanding. TAIL COLOURS The colours used for the Beaver tails (brown, blue and white) echo traditional Beaver colours and shades of brown and blue used in the Beaver hat and flag. -

Supervision Guide for Scouting Activities the Two-Scouter Rule, Youth:Scouter Ratios and Scouter Team Composition

SCOUTS CANADA GUIDELINE Supervision Guide for Scouting Activities The Two-Scouter Rule, Youth:Scouter Ratios and Scouter Team Composition Scouts Canada has Policies, Standards and Procedures with • While Scouter supervision is not always required for Troops mandatory requirements and actions that relate to Section and Companies, when Scouters are present there must supervision that Scouters must use to ensure adherence to be at least two. program quality and safety. This guideline provides further • Risk management for certain types of activities may require information and examples to help Scouters meet or exceed additional Scouters to be present to ensure a safe experience the requirements. for everyone. Scouter Team Composition What is a Scouter? The team of volunteers who facilitate the Scouting program for A Scouter is a volunteer member of Scouts Canada that is 14 a single Section is called the Scouter Team. Notwithstanding the years of age or older and has met the screening and training Two-Scouter Rule and Youth:Scouter ratio, each Scouter Team will requirements in the Scouts Canada Volunteer Screening have at least two registered Scouters, both of which are over the Procedure. age of 18, and one who functions as the Section Contact Scouter. The Two-Scouter Rule Furthermore: The Two-Scouter Rule is the requirement for two registered • Additional Scouters for Colonies, Packs and Troop must be over the age of 14. Scouters to be with youth at all times. Notwithstanding Section • The Section Contact Scouter for Companies must be over ratios, two Scouters must always be within the field of view and the age of 21. -

Un Monde, Une Promesse De Paix Mais Laquelle?

DOMINIC SIMARD UN MONDE, UNE PROMESSE DE PAIX MAIS LAQUELLE? Construction collective de l'image de paix chez les participants au 21 e rassemblement mondial du Mouvement scout (Angleterre, 2007). Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures de l'Université Laval dans le cadre du programme de maîtrise en anthropologie pour l'obtention du grade de maître ès arts (M.A.) DÉPARTEMENT D'ANTHROPOLOGIE FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES SOCIALES UNIVERSITÉ LAV AL QUÉBEC 2009 © Dominic Simard, 2009 Résumé Ce mémoire porte sur le plus grand mouvement de jeunesse dans le monde actuel: le . Mouvement scout, qui a célébré en 2007 son centième anniversaire. Dans le cadre d'un 21 e rassemblement mondial qui eu lieu en Angleterre au mois de juillet 2007, près de 40 000 scouts provenant de 156 pays ont passé 12 jours ensemble, fidèles au thème de l'évènement: « Un monde, une promesse ». Ils ont fait valoir, collectivement, un discours de paix imprégné de l'envergure et de l'effervescence d'un tel « rendez-vous » mondial. La recherche qui est présentée dans ce mémoire s'est penchée sur la nature du discours de paix construit lors de ce grand « Jamboree» scout. 111 Avant-propos Dans le domaine de la recherche en sciences sociales et plus particulièrement au stade embryonnaire d'un projet de maÎtrise en anthropologie sociale et culturelle, il me semble bien que l'aventure commence en profondeur: sous le continent de 'la clarté, dans ,l'eau trouble d'une foule d'idées. Il faut donc savoir s'élancer, sauter, bras ouverts, comme le font ces plongeurs de La Quebrado, du haut de ' leur pierre. -

2021 Roll of Honour Saying Thank You

Awards issued between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2020 (Updated 17/03/21) Contents Saying thank you 3 National Honours 4 World Scouting 6 Meritorious Conduct and Gallantry Awards 7 Good Service Awards 11 Future recognition 77 Please note Edits County: Although in some parts of the We aim to ensure that all recipients are British Isles Scout Counties are known listed correctly in this document, as Areas, Islands, Regions (Scotland) - however if you don’t see your name or and in one case Bailiwick, for ease of you see a mistake, please notify the reading, this publication simply refers to Awards Team on [email protected]. County/Counties. Published by The Scout Association, Awards are listed in first name Gilwell Park, Chingford, London E4 7QW alphabetical order under the location Copyright 2019 The Scout Association which nominated/approved the award. Registered Charity number 306101/SC038437 #SkillsForLife 2021 Roll of honour Saying thank you We’d just like to say thank you. Over the past year in my role I have been privileged to witness many examples across the UK of the You, our brilliant volunteers and staff, make Scouts astounding hard work of so many adult volunteers happen. It’s as simple as that. Without your and staff who make Scouts a real adventure for kindness and commitment we wouldn’t be able to young people. In the unusual year that it has been, I offer the incredible opportunities we give to our have met more people than ever due to the power young people, helping them gain skills for life. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Player Development and Scouting

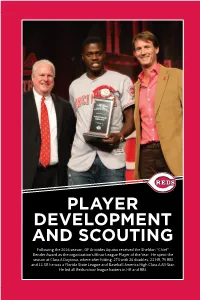

PLAYER DEVELOPMENT PLAYER DEVELOPMENT AND SCOUTING Following the 2016 season, OF Aristides Aquino received the Sheldon “Chief” Bender Award as the organization’s Minor League Player of the Year. He spent the season at Class A Daytona, where after hitting .273 with 26 doubles, 23 HR, 79 RBI and 11 SB he was a Florida State League and Baseball America High Class A All-Star. He led all Reds minor league batters in HR and RBI. CINCINNATI REDS MEDIA GUIDE 193 PLAYER DEVELOPMENT 2017 PLAYER DEVELOPMENT AND PLAYER SCOUTING PLAYER DEVELOPMENT SCOUTING SUPERVISORS Jeff Graupe ........................Senior Director, Player Development Charlie Aliano ..........................................................South Texas Melissa Hill ........................Coordinator, Baseball Administration Rich Bordi ........................................... Northern California, Reno Mark Heil ........................................Player Development Analyst Jeff Brookens ................................Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, Mike Saverino ................................Arizona Operations Manager Washington DC, Pennsylvania Branden Croteau .... Assistant to Arizona Operations Manager Sean Buckley ....................................................................Florida Charlie Rodriguez ......Assistant to Arizona Operations Manager John Ceprini ........Maine, NH, VT, RI, CT, MA, NYC/Long Island Jonathan Snyder ..................Minor League Equipment Manager Dan Cholowsky ...............Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, John Bryk ............................