Handbook for the Final Honours Course In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cœur, Temps and Monde in Le Forçat Innocent of Supervielle: a Poet’S Existential Metaphors of Prison and Shelter

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 33 Issue 1 Article 8 1-1-2009 Cœur, Temps and Monde in Le forçat innocent of Supervielle: A Poet’s Existential Metaphors of Prison and Shelter Franck Dalmas Stony Brook University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Dalmas, Franck (2009) "Cœur, Temps and Monde in Le forçat innocent of Supervielle: A Poet’s Existential Metaphors of Prison and Shelter," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 33: Iss. 1, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1695 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cœur, Temps and Monde in Le forçat innocent of Supervielle: A Poet’s Existential Metaphors of Prison and Shelter Abstract Poet Jules Supervielle has a marginal status in twentieth-century French literature as he was not engaged in any prominent movement of his time (Symbolism, Futurism, or Surrealism). In that regard, his poetry is neither nationally colored nor aesthetically connoted. It might well be the reason for his lacking consideration in the literary canon. But these differences must get our special attention. Supervielle was not born in France and he was to live and write his works in a state of existential angst, divided, as he always felt, between his native Uruguay and his French legacy. -

Coloquio Jules Supervielle

COLOQUIO JULES SUPERVIELLE Coordinador: ]osé Pedro Dîaz - Actas del Coloquio Supervielle 25, 26 y 27 de octubre de 1995 Montevideo - Uruguay Ministère des Affaires Etrangères Ambassade de France en Uruguay Ediciones de la Banda Oriental 1 PREFACIO· Solo en estos aiios, en esta ûltima década del siglo, se nos hizo posible estudiar y celebrar, en compafifa de escritores y profesores universitarios de varios pafses, la obra de los Ires poetas que el Uruguay dio a Francia, integrândola asf de marrera mas viva a nuestra cu_ltura. Con intervalos de solo un par de afios se cumplieron 1 en Francia y en Uruguay 1 tres encuentros en los que se estudiaron las obras de Isidore Ducasse, Jules Laforgue y Jules Supervielle. El resultado de los dos primeros encuentros fue recogido en dos vohimenes: el primero, que reune los trabajos presentados en el coloquio de Montevideo de 1992, lleva el tftulo de "Lautréamont & Laforgue: La quête des origines" y fue editado por la Academia Nacional de Letras del Uruguay: el segundo contiene el conjunto de los trabajos lefdos en las sesiones que ~e llevaron a cabo en las ciudades francesas de Pau y de Tarbes en· 1994, y se titula "Lautréamont et Laforgue dans son siècle": este integra los "Cahiers Lautréamont", livraisons XXXI-XXXII, que se editan en Francia. Tanto la organizaci6n de estas encuentros, coma la posterior publîcaci6n de los trabajos que se presentaron, es fruto de la generosa disposiciôn del Servicio Cultural de la Embajada de Francia en nuestro pais y en particular del empefio de uno de sus mâs entusiastas integrantes, el Prof. -

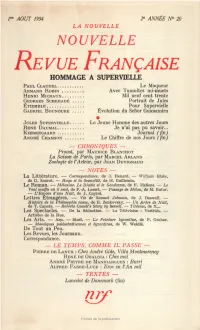

La N.R.F. (Aout 1954) (Hommage a Jules Supervielle)

Extrait de la publication Extrait de la publication BULLETIN D'AOUT 1954 SUPPLÉMENT A LA NOUVELLE N. R. F. r DU ler AOUT 1954 N° 20 Tjtrf- PUBLICATIONS DE JUILLET Les ouvrages analysés dans cette rubrique sont ceux dont la mise en vente a été prévue pour le courant du mois. Il est cependant possible que, pour des raisons techniques, la mise en vente de certains d'entre eux se trouve reportée plus tard. ROMANS MAHIAS (Claude) LA PART DU DOUTE. Cet étrange récit se situe en 1943, dans le Jura, à la frontière suisse. Marc, un jeune moniteur, passe là ses vacances, avec une colonie d'enfants sous-alimentés auxquels on essaie de refaire une mine. Au bout de quelques jours, un second moni- teur, Serge, un peu plus âgé que Marc, vient le rejoindre et partager ses respon- sabilités. Mais Serge est un personnage inquiétant. Il exerce sur certains enfants de la colo- nie un redoutable ascendant. Quiest, en réalité, ce nouveau venu ? Il n'a ni le phy- sique, ni l'esprit d'un moniteur bénévole de colonie de vacances. Son comporte- ment est singulier. Il est d'une nervosité excessive, garde un revolver dans sa valise, entretient des relations amoureuses avec une mystérieuse jeune femme blonde. Les jeux mêmes qu'il impose aux enfants ont quelque chose de suspect et de mal- sain. Ainsi, il les lance à la recherche d'un prétendu trésor qui serait caché depuis des siècles dans un château en ruine du voisinage. Trouver un trésor, voilà une occupation bien passionnante pour des enfantsMarc flaire quelque chose de louche dans cette idée il soupçonne.qu'elle dissimule un dessein dangereux. -

La Poésie De Jules Supervielle

LA POÉSIE DE JULES SUPERVIELLE Si Jules Super-vielle a, d'assez bonne heure, vu s'ouvrir devant lui les portes de la Nouvelle Revue française, pourvoyeuse des gloires poétiques de ce temps, il ne l'a pas dû, comme tels de ses illustres confrères, à ces recherches de style ou ces innovations calculées de langage, requises du postulant par cette maison exclusive. C'est qu'il n'avait nul besoin de recourir à des artifices pour se créer une originalité. Son originalité, il la trouvait en lui-même sans con• trainte, comme il avait eu la fantaisie, quoique Béarnais et Basque d'origine, de naître, vers le déclin du xixe siècle à Montevideo, ce qu'avaient fait, avant lui, Jules Laforgue et Lautréamont. C'est en Uruguay qu'il passa presque toute son enfance, encore qu'âgé de quelques mois, il eût eu le malheur de perdre ses parents au cours d'un premier voyage en France. Il est toujours resté en lui un peu de VHomme de la Pampa, titre d'un de ses romans, ou plutôt, d'une de ses divagations romanesques publiée en 1923. Un premier recueil de poésies, Comme des voiliers, attestant par le vocable ce que son auteur doit à la mer et aux voyages, avait paru dès 1910, mais c'est par son second, Les Poèmes de Vhumour triste, imprimés en 1919 par François Bernouard, à la Belle Edition, que Jules Supervielle se définit lui-même exactement. Comme le jazz a introduit l'humour dans la musique, cet autre enfant des Amériques a introduit l'humour dans la poésie. -

English Or German, There Are Far Fewer

Autographs of Fate and the Fate of Autographs Books often forever remain where they were born. Or, on the contrary, as if driven by some force, move along the face of the earth, from continent to continent, from one civilization to another. This movement usually proceeds calmly; it has long been a traditional form of the mutual enrichment of cultures. But in this natural flow, extraordinary events may interfere. Like birds to which rings have been attached, sent out to unknown destinations by raging elements, a book sometimes tells us about the trials it has experienced. And about the trials of those who somehow or other have been connected to it. Such thoughts, together with a feeling of vague anxiety, arise in me every time when in Minsk, most often in the National Library of Belarus, a book in French with an inscription by the author falls into my hands. Why are there so many specifically French autographs? In other languages, English or German, there are far fewer. Why for the most part do they belong to the interwar decades, i.e. the 20’s-30’s of the twentieth century? Why are these autographs mostly intended for recipients whose names are clearly not Romance language ones? Why in some cases do the names of the authors and recipients belong to people whose lives were brutally cut short during the Nazi occupation? What was the fate of those who were spared by events and time? These questions demand answers no matter whether the signature belongs to a person who did not leave a visible trace in the memory of future generations or we are talking about names that, like the names of Léon Blum and Marcel Proust, marked a whole period of the political and cultural history of France. -

Tarsila Do Amaral's Abaporu

© Michele Greet, 2015 Devouring Surrealism: Tarsila do Amaral’s Abaporu Michele Greet Various scholars have suggested a contiguity or affinity between Brazilian artist Tarsila do Amaral’s iconic painting Abaporu (1928) and surrealism; none have engaged in an in-depth analysis of her actual relationship with surrealism, however. This close reading of Abaporu will demonstrate that Amaral deliberately and systematically engaged with the tenets and formal languages of surrealism. Her engagement was not one of pure emulation; instead she turned the surrealists’ penchant for satire and desire to disrupt hierarchical schema back on itself, parodying the images and ideas put forth by the movement to create a counter modernism. Amaral’s sardonic appropriation of surrealism’s formal languages and subversive strategies was the very factor that made Abaporu the catalyst of the anthropophagite Movement. On 11 January 1928 the Brazilian artist Tarsila do Amaral presented a painting to her husband, the writer and intellectual Oswald de Andrade, for his birthday. Amaral described the painting, which Andrade would later entitle Abaporu (Fig. 1), or ‘person who eats,’ as: ‘a monstrous figure, with enormous feet planted on the Brazilian earth next to a cactus.’1 Scholars have long acknowledged Abaporu as a crucial work in Amaral’s career as well as an icon of early twentieth-century Latin American art. The painting marked the beginning of her anthropophagite phase, a period from about 1928 until 1930 during which Amaral departed from the densely packed compositions of urban São Paulo and the Brazilian countryside that characterized her Pau-Brazil period to paint scenes of one or two isolated figures in lush tropical dreamscapes.2 Despite the dream-like quality of these pictures, Amaral’s engagement with surrealism in Abaporu (and the other paintings of the period), while occasionally acknowledged, has not been fully interrogated. -

Jorge Guillén, Traductor De Supervielle

JORGE GUILLÉN, TRADUCTOR DE SUPERVIELLE ALICIA PIQUER DESVAUX UNIVERSITAT DE BARCELONA De todos es conocida la importante labor de traducción de poesía y de prosa extranjera llevada a cabo por los poetas de la generación del 27 (J.M. Rozas, 1986), y concretamente la brillante tarea como traductor de poetas de Jorge Guillen. Actividad que desarrolla a lo largo de su vida (bajo formas diversas: versiones, variaciones, homenajes...) y que es inseparable de su reflexión sobre el lenguaje y la creación poética. Sus versiones del Cementerio Marino de Paul Valéry (así como las de La durmiente, El silfo o Las granadas) se destacan siempre elogiosamente del conjunto de poetas franceses que retienen su atención (Rimbaud, Malkrmé, Toulet, Claudel, Saint-John Perse, Jean Cassou, o Supervielle), sin embargo queremos hoy destacar sus reflexiones en torno a la obra de Jules Supervielle, menos citadas aunque igualmente muy significativas, como vamos a ver a continuación. Otros poetas contemporáneos suyos han traducido a Supervielle con igual fortuna,6 pero el entusiasmo que despierta en Guillén es muy notable y duradero,7 y de ello tenemos constancia al leer las crónicas que escribió desde París para varios diarios y revistas como El Norte de Castilla, índice, La Verdad, España o La Pluma (recogidos en Hacia Cántico, Escritos de los años 20, 1980) y concretamente las del diario La Libertad (objeto de una reciente edición: Desde Paris, 2000), que van a ser objeto de nuestra atención. Como es característico 6 Especialmente Gerardo Diego, Tántalo. Versiones poéticas (Madrid, Agora, 1960). Reed. en Segunda Antología de sus versos(1941-1967) (Madrid, Espasa-Calpe, 1967). -

Yale Department of French News Fall 2018

yale department of french fall 2018 AS I PAUSE TO CONTEMPLATE the senior level as well, and we are hoping GREETINGS another busy and successful year in to have very exciting news to announce in the Yale Department of French, I am this regard shortly. FROM THE deeply grateful to everyone who made We were very happy to welcome back it possible. I am especially grateful to ALYSON WATERS to teaching this past CHAIR PIERRE SAINT-AMAND for agreeing year. As many of you know, in addition to to be the Director of Graduate Studies editing Yale French Studies, Alyson has a so soon after arriving at Yale, and for the thriving career as a translator. Now that extremely effective work he did preparing she is once again teaching her popular our students for the job market. I am courses on translation, we have been ALICE KAPLAN equally grateful to for able to add a translation track to our filling in for Pierre as DGS when he went undergraduate major. This year, we will TOM CONNOLLY on leave in the Spring. also experiment with two new courses on did a wonderful job during his two years French for the professions—one devoted as Director of Undergraduate Studies to medicine and one to business—which and will now be handing over the reins to will be taught by MORGANE CADIEU . I am happy to say our new lector, RUTH KOIZIM that has agreed to stay on LÉO TERTRAIN, as the director of our language program. (left)who joins Over the past year, we conducted a us fresh from th th major international open-rank search in the completing a PhD fields of 16 and/or 17 -century French at Cornell in 2016. -

ENCLS-Newslettermay2016

N ewsletter No. 2, May 2016 Editor: Olga Springer 1 . C A L L S F O R P A P E R S A N D S E M I N A R P ARTICIPATION I N S I D E T H I S I SSUE ( BY DEADLINE ) 1 Calls for Papers and Romantic Legacies (National Chengchi University (NCCU), Taipei, Taiwan) Seminar Participation / 18-19 November 2016 Appels à Deadline: 15 May 2016 Communication et Keynote Speakers: Rachel Bowlby, FBA (Comparative Literature, Princeton Séminaires University/English, University College London): “Romantic Walking and Railway 2 Calls for Contributions / Realism”; Arthur Versluis (Religious Studies, Michigan State University): “Platonism, Its Appels à Contribution Heirs, and the Last Romantic”. In his seminal book The Roots of Romanticism (1999), Isaiah Berlin regards 3 Publications and Romanticism as “the largest recent movement to transform the lives and the thoughts Doctoral Theses of the Western world.” Indeed, Romantic ideas and attitudes—embraced by Goethe, Hegel, Sade, de Staël, Rousseau, Baudelaire, Wollstonecraft, Wordsworth, Coleridge, 4 Funding Alerts / Shelley, Beethoven, Schubert, Poe, Emerson, Thoreau, Dickinson, Turner, and Annonces de Finance- Delacroix, to name but a few—not merely changed the course of history in the West in ment de Recherche the late-eighteenth and nineteenth centuries but helped to fashion twentieth-century 5 Positions democracy, environmentalism, Surrealism, fascist nationalism, communist Announcements universalism, spiritualism, social liberalism, and so forth in the West as well as in the (Teaching, Research, East. This two-day interdisciplinary conference aims to bring together academics from etc.) / Annonces de across the humanities and social sciences to explore the full spectrum of possible Postes (Enseignement, Romanticisms, the germination, maturation, and development of this heritage on both Recherche, etc.) sides of the Atlantic and its afterlife in our global capitalist culture today. -

French Literature 1950–2000: an Anthology

French literature 1950–2000: An Anthology Edited by Sharad Chandra French literature 1950–2000: An Anthology Edited by Sharad Chandra 1 Preface Compiling this anthology has been a great delight for me in spite of the arduous task of making selections—of authors and of excerpts, since in literature it is never easy to decide whom to keep, whom to leave out; then, to use the excerpt from what work which ones to leave out. Nevertheless, the choice had to be made. I have finally been able to select, fifty–six authors which, in my view, score over others in merit, in literary significance, as also in best illustrating the trends and tendencies of the period under study. The number or length of the excerpt(s) is in no way, indicative of the literary distinction of a particular author, rather of a characteristic trait or a singuliar peculiarity of the work contributing to a current concept or introducing a new feature. A major hurdle in the way was of locating and acquiring English translations of selected works— since, in order to save time as well as to avoid complications of buying translation rights, I decided to use only the existing translations. This limitation did slightly restrict my field but has not, in any way, impaired the comprehensively of the presentation of French literature from 1950 to the end of the century. To make the anthology as complete as possible, interesting information on exotic literary practices like ‘Oulipo’, names of French Nobel laureates, the long list of French literary Prizes, and a chronology of Socio-political events of the period has been provided in the Appendix. -

GILLIAM, B. June, 1927- TEACHING FRENCH POETRY in the AMERICAN SECONDARY SCHOOL

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 7 0 - 6 7 8 2 ") GILLIAM, B. June, 1927- TEACHING FRENCH POETRY IN THE AMERICAN SECONDARY SCHOOL. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 Language and Literature, linguistics University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © _ B. June Gilliam 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TEACHING FRENCH POETRY IN THE AMERICAN SECONDARY SCHOOL DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By B. June Gilliam, Ph.B., M,A. ******* The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by College of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A list of all of the individuals whose encouragement, enthu- 0 siasm for learning and example of energetic scholarship have influ enced the writer would be impossible to include in this restricted space. Such a list is both too impersonal and too inadequate a wit ness of the writer's indebtedness. The memory of Dr. Emile de Sauz/ permeates the entire study as it has the career of its writer. The warmth and erudition of Dr. Henri Peyre rekindled a smoldering inter est in literature. The professional promotion given by Dr. David Dougherty and the encouragement and opportunity for experimentation given by the writer's major adviser, Dr. Edward D. Allen, cannot be sufficiently acknowledged by so brief a mention. Insights into the nature and possibilities of the ideal teacher education are due to Professor Lennard 0. Andrews. The insights into creative teaching are the result of conferences with Professor Ross Mooney. Professor | Frank Zidonis guided the graphic presentation of the theory. -

Jules Supervielle : Pour Une Poétique De La Transparence Margaret Michèle Cook

Document generated on 09/23/2021 10:44 a.m. Études françaises Jules Supervielle : pour une poétique de la transparence Margaret Michèle Cook L’ordinaire de la poésie Article abstract Volume 33, Number 2, automne 1997 La poétique de la transparence de Jules Supervielle ramène la poésie à l'ordinaire et au quotidien. À l'intérieur de ce monde, l'irréel est apprivoisé, ce URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/036066ar qui permet au poète de rejoindre de nouveau l'ordinaire dans sa profondeur. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/036066ar Une nouvelle réalité et une symbiose avec l'univers sont ainsi recherchées à travers cette face cachée du monde. See table of contents Publisher(s) Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal ISSN 0014-2085 (print) 1492-1405 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Cook, M. M. (1997). Jules Supervielle : pour une poétique de la transparence. Études françaises, 33(2), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.7202/036066ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 1997 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Jules Supervielle : pour une poétique de la transparence MARGARET MICHÈLE COOK Qualifier la poésie de transparente, si ce n'est d'ordinaire, va à l'encontre d'une certaine conception de la poésie qui veut que celle-ci soit obscure, illisible et même incompréhensible.