The Early History of the Sutro Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 John Renbourn. John Renbourn Est Un Guitariste Folk Anglais Né En

John Renbourn . John Renbourn est un guitariste folk anglais né en 1944 en Angleterre appartenant à la mouvance créée par Davey Graham (co-auteur de « Angie » avec Janch, qu’interpréta Paul Simon sur son premier disque). Il est connu du public pour ses collaborations avec le guitariste Bert Jansch, ainsi que pour son travail au sein du groupe folk qu’il a formé avec lui et d’autres, le Pentangle, mais a toujours mené une carrière solo avant, pendant et après l'activité du groupe (de 1967 à 1973). Ecoutons le : White house blues (du disque Faro Annie ) : http://official.fm/tracks/323234 Little Sadie (du disque Faro Annie ) : http://official.fm/tracks/323235 Shake, shake mama (du disque Faro Annie ) : http://official.fm/tracks/323236 John Renbourn a étudié la guitare classique à l'école, et c'est pendant cette période qu'il a fait la connaissance de la Musique Primitive. Dans les années 1950, il fut grandement inspiré par l'originalité décalée du Skiffle et ce fut pour lui l'occasion d'explorer le travail d'artistes tels que Leadbelly, Josh White et Big Bill Broonzy. Au début des années soixante, la mode populaire était au Rhythm and Blues, dont se réclamaient des groupes tels que les Rolling stones. Cette émergence de la musique noire américaine au Royaume-Uni tient beaucoup à l'influence de guitaristes acoustiques tels que Davey Graham. En 1961, Renbourn a ainsi tourné dans le Sud- Ouest des États-Unis avec Mac MacLeod, tour de chant répété en 1963. Pendant ses études au Kingston College of Art de Londres, Renbourn fit brièvement partie d'un groupe de Rhythm and Blues. -

The Ingham County News

NO. 41 VOL. LU. MASON. MICH.. THURSDAY. OCTOBER 13. 1910. Bargains in Groceries lEVERmS at G. S. Thorburn's 1 W Cash Grocery 25 lbs Moss Rose Floiu- 75e :i bushel PoLatocs VDC 25 lbs Lily White Flour SOc 1 bushel Tomatoes SOc 25 lbs Best Flour 75c Fresh Melons every day, each ^ DC 25 lbs I-Ienkle Bread Flour 85c Apples, peck - ^Oc 25 lbs Gold Medal Flour 95c All Rradcs Iflour •--''So (;anvas Gloves, loe pair, ;i pair 250 25 lbs H. & E. Gran. Sugar $1.48 :r)airy and Creamery Jiuller for sale. Pulverized Sugar, per lb 8c A Kood Broom 'lOc. Loaf Sugar, per lb 8c 10 llttaraham Mi^ 1 lb Santos and Rio Coffee 15c :i()ll)s Meal '^5(1 Trv lloinz Apple liuttcr, line. 10 lbs Pure Buckwheat ,35c Kr'usli Hrcad and Friedcakcs daily. Henkle Prepared Buckwheat,. 9c 1 gal pail Corn Syrup 35c GEO. H. LEVERETT. Mi gal pail Corn Syrup 18c Itiith l>hi)ncs. 2-lb can Corn Syrup 10c Leader Condensed Milk 10c Ann & Hammer Soda 5c |luj)ham(!5outttij|lcutsi Cold Blast Lantern Globes 8c Eiil.iU'nd 11.H.I10 I'list. onlce, Mason, No. 1 Lamp Chimney 5c iissucDtid-cliiss niattur. Best Eocene Oil, gal 10c I'uljllsliuil Kvory Tluirsdiiy by •I'he uprising in Portugal was iho most Important news event of tUe week King M.nuuel wns variously reported a cnplive and 25 lb. sack Suffar *1.'10 News Snapshots a fleeing monnrch. The consecration of St. Patrick's cnfheilral In New York was one ot the greatest events in American Cath (With $1,50 other groceries) Sweet Potatoes, peck , iiOc TERmS olic history. -

Trasmessi Di Recente

Artist Title Album 10,000 Maniacs These Days Rubàiyàt: Elektra's 40th Anniversary A Fil De Ciel Lhi carn marinas/Coda A Fil De Ciel A.J. & The Rockin' Trio You Should Have Known Rockin' The Blues Aaron Tippin A Door Greatest Hits...and then some Abraham Weaver What's Going On Lost And Found Actores Alidos Cantu a ballu Actores Alidos: Canti Delle Donne Sarde Adam Carroll Love Song For My Family Far Away Blues Alejandro Escovedo Notes on Air The Boxing Mirror Ambrogio Sparagna Il Paese Con Le Ali Il Paese Con Le Ali Angel Unzu Colores Tiempo de Busqueda Antonio Di Martino & Fabrizio Cammarata Un mondo raro Un Mondo Raro Aryeh Frankfurter The Butterfly Celtic Harp Ashley Lian Limbs Dear Audrey Auld Parasitic Publicist Blues Bal O'Gadjo Les Cordes m'usent En Route! BandaJorona Ma quale amore è Mettece sopra Barbecue Bob Atlanta Moan The Essential Barefoot Jerry Summit Ridge Drive Keys To The Country Barry McLoughlin We've Got Love Pieces Beach 5 Beach 5 Beach 5 Beppe Gambetta Fandango per la Bionda Blu Di Genova Big Bill Broonzy See See Rider One Beer, One Blues Big Jack Reynolds Made It Up In Your Mind That's A Good Way To Get To Heaven Big Maceo Anytime For You Worried Life Blues Big Mama Thornton Unlucky Girl In Europe Big Mama Thornton Mischievous Boogie The Complete 1950-1961 Big Time Sarah Don't Make Me Pay A Million Of You Bill Boyd's Cowboy Ramblers I'm a High Steppin' Daddy Bill Boyd 1937-1938 Bill Monroe Mule Skinner Blues The Early Years 16/09/2021 - 16/09/2021 Page 1 of 13 Artist Title Album Bill Morrissey Walk Down These Streets Night Train Billie Pierce & Dede Pierce Bye And Bye (Take 2) Primitive Piano Billy Burnette Beautiful Distraction Rock'n'Roll With It Birdthrower Days of Never Before Birdthrower Blackjack Beauty of My Dreams 10 Years Of European World Of Bluegrass Blind Connie Rosemond Heavenly Sunshine Gospel Classics Vol. -

Rosemary Lane 1996-99

Introducing Rosemary Lane 1996-99 hese six editions of Rosemary Lane from T1996-99 cover vibrant years in the post- Pentangle musical projects of Bert Jansch, Jacqui McShee and John Renbourn. Bert married Loren Auerbach, launched his successful come-back album When the Circus Come to Town, brought his own musical circus to town by taking up regular residency with friends at the popular 12- Bar Club in Denmark Street, released a bootleg album from that experience, toured around the world and followed up with the memorable Toy Balloon from the studio. Jacqui put out the first fruits of her collaboration with Gerry Conway and Spencer Cousins in the long-awaited About Thyme album, began work on the follow-up Passe Avant whilst touring Europe and the UK both with her own band and John Renbourn. John himself had started working on arrangements that eventually emerged on the album Traveller’s Prayer, but in the meantime was overtaken by the release of the Lost Sessions album of recordings from the early ‘70’s, whilst touring the US and Europe which also gave rise to the Live in Italy collection. He played with Jacqui, Stefan Grossman, Isaac Guillory, Archie Fisher, Wizz Jones and even teamed up again with Dorris Henderson for some impromptu concerts re-visiting their early 1960’s collaborations. So when you read the magazines now, you will quickly discover they depict three flourishing talents fully- engaged with their music and thrilling audiences wherever they performed. he magazine was despatched to all four corners of the British Isles. TInternationally the most popular continent was Europe headed up by readers in Germany, Italy and Norway with fewer in Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, France, the Republic of Ireland, Spain, Portugal and Sweden. -

Palm Desert History

History Of Palm Desert John Fraim John Fraim 189 Keswick Drive New Albany, OH 43054 760-844-2595 [email protected] www.symbolism.org © 2013 – John Fraim Special Thanks To Palm Desert Historical Society & Hal Rover Brett Romer Duchess Emerson Lincoln Powers Carla Breer Howard 2 “The desert has gone a-begging for a word of praise these many years. It never had a sacred poet; it has in me only a lover … This is a land of illusions and thin air. The vision is so cleared at times that the truth itself is deceptive.” John Charles Van Dyke The Desert (1901) “The other Desert - the real Desert - is not for the eyes of the superficial observer, or the fearful soul or the cynic. It is a land, the character of which is hidden except to those who come with friendliness and understanding. To these the Desert offers rare gifts … health-giving sunshine—a sky that is studded with diamonds—a breeze that bears no poison—a landscape of pastel colors such as no artist can duplicate—thorn-covered plants which during countless ages have clung tenaciously to life through heat and drought and wind and the depredations of thirsty animals, and yet each season send forth blossoms of exquisite coloring as a symbol of courage that has triumphed over terrifying obstacles. To those who come to the Desert with friendliness, it gives friendship; to those who come with courage, it gives new strength of character. Those seeking relaxation find release from the world of man-made troubles. For those seeking beauty, the Desert offers nature’s rarest artistry. -

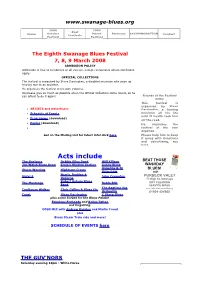

Acts Include

www.swanage-blues.org 2008 2009 Past Home October March Swanage ACCOMMODATION Contact Festivals Festival Festival The Eighth Swanage Blues Festival 7, 8, 9 March 2008 ADMISSION POLICY Admission is free to customers at all venues, except restaurants where conditions apply. OFFICIAL COLLECTIONS The festival is organised by Steve Darrington, a disabled musician who gave up touring due to an accident. He organises the festival at his own expense. So please give as much as possible when the Official Collectors come round, so he can afford to do it again! Friends of the Festival write: This festival is organised by Steve z ARTISTS and Advertisers Darrington, a touring z Schedule of Events musician all his life until ill health took him z Programme (download) off the road. z Poster (download) He organises the z festival at his own expense. Get on the Mailing List for latest info! click here Please help him to keep it going with donations and advertising, see here. Acts include The Guv'nors Debbie Giles Band Will Killeen BEAT THOSE Jon Walsh Blues Band Ernie's Rhythm Section Sonny Black WASHDAY Angelina & JC Storm Warning Hightown Crows BLUES! Grimshaw with Harris, Budden & Motel 6 John Crampton PURBECK VALET Osborne 73 High St, Swanage Robert Hokum Blues The Mustangs Robin Bibi DRY CLEANING Band SERVICE WASH The Ragtime Jug Coalhouse Walker Chris Collins & Blues Etc free collection and delivery Orchestra 01929 424900 Coast Steve Darrington C Sharp Blues plus some Sorbet for the Blues Palate! Fabulous Fezheads and Kellys Tattoo not forgetting OPEN MIC with Andrew Bazeley and Martin Froud plus Blues Steam Train ride and more! SCHEDULE OF EVENTS here THE GUV'NORS Saturday evening 10pm - White Horse The Guv'nors 20th Year Tour continues! Led by Bluesmaster Robert Hokum on guitar and vocals, this seven piece outfit plays the blues with psychedelic funk, acid jazz and Latin grooves. -

Melody-Maker-1968-10

MelodyAll-starline-up! Maker OCTOBER 19, 1968 is weekly BLUES HEROES. BINGOIN Page13 TOM JONES SELLERS ON TOUR Page 7 POP TODAY FILM AND TOMORROW BEM-LE Ringo Starr has signed for his second major film role. He is to appear with Peter Sellers in The Magic Christian, which goes into production in Britain early in the New Year. Ringo will play Sellers' son in the film which is scripted by Terry Southern,who co -wroteCandyand wrote the script for the new Jane Fonda film Barbarella. Candy isthe book which was filmedin Rome last year with Ringo playing a Mexi- can gardener. This wasthe drummer's first screenactingrole away fromtheother Beatles. The filmstill has not been shown in Britain. The newfilm,whichhasnomusical content at all, will be made in Britain. Peter Sellers is making some contributions to the script over the nestfeu, weeks. The Beatles neu double album has now been completed but Apple's Derek Taylor saidon Mondaythatnotitlehad been decided. the four Beatles are scheduled to leave Britain on holiday this weekend. They are going to different destinations "for a rest." George Harrison andhis wifePattiareflyingto America to stay with friendsbuttheplansof theothers were notre- vealed. Armstrong'sBritish Concert Nothinghasbeende- visit cided on a venue for the iscancelled Beatles' projected live ap- pearance, but Tayloragain LOUISARMSTRONG'SEuropean confirmed that the group tour, whichwas to have taken-stillin hospital would olav alive concert ina two-week before Christmas. "But It's season at the Wake- in the leg- was respondingto treat- Justaslikelytobeat field TheatreClub, startingDecem- ment. TwickenhamStudiosas ber 1, has been cancelled becauseof " Ispoketohismanager,Joe theAlbertHallor even Satchmo's ill health. -

John Renbourn Fingerstyle Guitar Free

FREE JOHN RENBOURN FINGERSTYLE GUITAR PDF John Renbourn | 120 pages | 01 Jun 2000 | Mel Bay Publications,U.S. | 9780786650248 | English | Missouri, United States John Renbourn Fingerstyle Guitar by John Renbourn Over the years I have gigged and recorded with a fair number of guitars, most of which I thought were the best in the world at the time. Much as you cherish and try to look after them though things happen - they get stolen, damaged or simply worn out and eventually have to be replaced. Those that do survive are hard to part with and usually wind up hanging on the wall. In the mid sixties my guitar idol was Davey Graham. I heard through the grapevine that an American serviceman on an airbase had one for sale and I had to have it. It was a J, nearly the same as Davey's and that was it for the old Scarth - musical considerations overruled by blind fanaticism. I found out later that Davey wasn't playing his by choice, he had owned a very nice Martin, gone to a party and come away with the Gibson, possibly without realising it! However, for me, it was a transformation. From 'Another Monday' right through into Pentangle it did the job - both acoustic and amplified. The J has lasted well, only one major repair as I recall. The back was smashed, courtesy of an airline - guitars into Airlines do not go as I've learned to my cost over the years. It is now resting down in the south of France in the care of my old friend Remy Froissart. -

April-May 2021

2013 KBA -BLUES SOCIETY OF THE YEAR IN THIS ISSUE: A special edition on Chicago Blues! -Chicago Blues - allaboutbluesmusic.com -Chicago Blues 1970s-to early Volume 28 No 3 April/May2021 1980s- bobcorritore.com Editor- Chick Cavallero -The Chicago Blues ‘Sound’ -Gone But Not Forgotten-Otis Rush- by Todd Beebe CHICAGO BLUES -Head Over Heels In Love With The Blues- by Rich Karpiel This article was reprinted from All About Blues -David Booker’s Manchester Music, an excellent site for the best in Blues writing, whether history, artists, the industry, or Memories Continued – Part 5 the records themselves. Check it out at -Down To the Last Two- by Jack https://www.allaboutbluesmusic.com Grace -CD Reviews The Blues was born in the Delta and grew up on –CBS Members Pages its journey from the country to the city, but the place it came of age was Chicago. -CBS Presidents Column -CBS Board of Directors Ballot When Muddy Waters got off the train from Mississippi in 1942, he soon noticed two things. CONTRIBUTERS TO THIS ISSUE: Chick First, he was going to need an electric guitar turned up loud to be heard over the noisy bar Cavallero, David Booker, Todd crowds. Secondly he needed a band, not with Beebe, Dan Willging, Jack Grace, horns like the ones he heard around him, but a https://www.allaboutbluesmusic. much louder version of the string band he had com, https://bobcorritore.com, back home in the Delta. His Uncle Joe (Brant) gave him an electric guitar and he set about Rich Karpiel, Kyle Borthick, forming the band. -

Ace Catalogue 2014

ace catalogue 2014 ACE • BIG BEAT • BGP • CHISWICK • GLOBESTYLE • KENT • KICKING MULE • SOUTHBOUND • TAKOMA • VANGUARD • WESTBOUND A alphabetic listing by artist 2013’s CDs and LPs are presented here with full details. See www.acerecords.com for complete information on every item. Artist Title Cat No Label Nathan Abshire With His Pine Master Of The Cajun Accordion: CDCHD 1348 Ace Grove Boys & The Balfa Brothers The Classic Swallow Recordings Top accordionist Nathan Abshire at his very best in the Cajun honky-tonk and revival eras of the 1960s and 1970s. Pine Grove Blues • Sur Le Courtableau • Tramp Sur La Rue • Lemonade Song • A Musician’s Life • Offshore Blues • Phil’s Waltz • I Don’t Hurt Anymore • Shamrock • If You Don’t Love Me • Service Blues • Partie A Grand Basile • Nathan’s Lafayette Two Step • Let Me Hold Your Hand • French Blues • La Noce A Josephine • Tracks Of My Buggy • J’etais Au Bal • Valse De Kaplan • Choupique Two Step • Dying In Misery • La Valse De Bayou Teche • Games People Play • Valse De Holly Beach • Fee-Fee Pon-Cho Academy Of St Martin-in-the-Fields Amadeus - Special Edition: FCD2 16002 (2CD) Ace Cond By Sir Neville Marriner The Director’s Cut Academy Of St Martin-in-the-Fields The English Patient FCD 16001 Ace Cond By Harry Rabinowitz Ace Of Cups It’s Bad For You But Buy It! CDWIKD 236 Big Beat Act I Act I CDSEWM 145 Southbound Roy Acuff Once More It’s Roy Acuff/ CDCHD 988 Ace King Of Country Music Roy Acuff & His Smokey Sings American Folk Songs/ CDCHD 999 Ace Mountain Boys Hand-Clapping Gospel Songs Cannonball -

Layout 1 Copy 3/1/19 6:44 PM Page 1

Scoop, March 8, 2019.qxp_Layout 1 copy 3/1/19 6:44 PM Page 1 4 - SCOOP U.S.A . - Friday, February 1, 2019 Celebrating 58 Years of Community News by Adelaide AbSdur-Rcahmoan opUSA Black History198 2 SCharono Carprentenr, broeadcar st journalist and tele - [email protected] vision host (BET) is born in England. 1985 (Reginald Alfred) Reggie Bush, Jr., National PISCES - February 19 - March 20 Football League player is born in Spring Valley, CA. 1991 (Lemuel) Lem Tucker, first African American to Pisces – The Dreamer work as a television network reporter dies. Generous, kind and thoughtful. Very creative 1993 B. Doyle Mitchell, chairman and president of the and imaginative. May become secretive and fourth largest minority owned bank dies in Washington, vague. Sensitive. Don’t like details. Dreamy DC. and unrealistic. Sympathetic and loving. Kind. 1994 Kofi Siriboe, actor (The Longshots) is born in Los Unselfish. Good Kisser. Beautiful. Angeles, CA. 1994 Cornelius Robinson Coffee, first African Ameri - Aquamarine is the stone for the month of March can to hold both a pilot’s and mechanic’s license and the In legends, aquamarine has its origin in the treasure chests first to establish an aeronautical school in the US dies in of the mermaid. It is though to bring good luck and fortune Chicago, IL. to sailors. It is believed that if a person dreams of aquama- 2003 (John Henry Kendricks) Hank Ballard, singer and rine he or she will meet new friends. According to ancient songwriter (The Twist) dies in Los Angeles, CA. traditions aquamarine will guarantee a long and happy 2001 Jessie M. -

Starling Is Published and Edited by Hank and Lesleigh Luttrell, at Iloo Locust St., Columbia, Missouri 65201

cover - Doug Lovenstein colophon-contents. ........ ................... 2 Your Man in Missouri (editorial) - Hank, . • 3 Mss. Found in Bottles (column) - Banks MeBane 4 Pangaea, part I: SF Rock - Hank...................................6 The Polymorphous Prevert, part I: Green Dream - Greg Shaw ......»••••• 9 The Ministry, of Love (poem) - Chester Anderson. .....................................•..........................14 Words from Readers (letter column) ..... 15 Pangaea part II: May the Long Time Sun Shine- Lesleigh Luttrell & James Schumacher. 27 Heron (poem) - James Schumacker....................... 33 Pierce! Section Second Impoundation (non-fact artical) - Don D’Ammassa........................................ 3^ The First Foundation - Jim Turner. .... 36 With Malice Toward All (book cdimn) - Joe Sanders ..... .............................................. 38 Backcover - Mike Symes, from the science fiction masterpiece, Their Satanic Majesties Request. INTERIOR ART ' ' ' . Foster 17 Gaughan 2, 21 Gilbert 19, 24 ‘ • Lovenstein 31 • Rostler 6,7,8, 16, 20, 29 . , . Symes 23 Lettering & Layout: Hank- , Starling is published and edited by Hank and Lesleigh Luttrell, at IlOo Locust St., Columbia, Missouri 65201. It is available with 300 or 2/500, fanzines in trade, or with contribution of artwork, articles, a letter of comment, or any thing else that you can convince us is worth publishing. May, 1970 issue. Published quarterly. This issue helps celebrate the 40th Anniversary of fanzines. Weltanshauung Publication #7. I haven’t put together a mailing .list for this Stirling yet, but I’m sure that 3 groups of people will be getting it: 1) fans familiar with Starling: . Dear Friends, I'm sorry for the long delay between issues; I’d particularly like to extend my •apologies to contributers, for folding their work for such a. long time.