Integration and Macroevolutionary Patterns in the Pollination Biology of Conifers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fossils and Plant Phylogeny1

American Journal of Botany 91(10): 1683±1699. 2004. FOSSILS AND PLANT PHYLOGENY1 PETER R. CRANE,2,5 PATRICK HERENDEEN,3 AND ELSE MARIE FRIIS4 2Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, UK; 3Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington DC 20052 USA; 4Department of Palaeobotany, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, S-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden Developing a detailed estimate of plant phylogeny is the key ®rst step toward a more sophisticated and particularized understanding of plant evolution. At many levels in the hierarchy of plant life, it will be impossible to develop an adequate understanding of plant phylogeny without taking into account the additional diversity provided by fossil plants. This is especially the case for relatively deep divergences among extant lineages that have a long evolutionary history and in which much of the relevant diversity has been lost by extinction. In such circumstances, attempts to integrate data and interpretations from extant and fossil plants stand the best chance of success. For this to be possible, what will be required is meticulous and thorough descriptions of fossil material, thoughtful and rigorous analysis of characters, and careful comparison of extant and fossil taxa, as a basis for determining their systematic relationships. Key words: angiosperms; fossils; paleobotany; phylogeny; spermatophytes; tracheophytes. Most biological processes, such as reproduction or growth distic context, neither fossils nor their stratigraphic position and development, can only be studied directly or manipulated have any special role in inferring phylogeny, and although experimentally using living organisms. Nevertheless, much of more complex models have been developed (see Fisher, 1994; what we have inferred about the large-scale processes of plant Huelsenbeck, 1994), these have not been widely adopted. -

Recent Changes in the Names of New Zealand Tree and Shrub Species

-- -- - Recent changes in the names of New Zealand tree and shrub species - Since the publication of 'Flora of New Zealand' Volume 1 (A- iii) Podocarpus dacydioides Dacrycarpus ducydioides lan 1961),covering indigenous ferns, conifers and dicots, there (iii)Podocarpus ferrugzneus Prumnopitys ferruginea have been major advances in taxonomic research and the clas- Podocarpus spicatus Prumnopitys taxijolia sification of many plant groups revised accordingly. Most of (iv1 Dacrydium cupressinum (unchanged) these changes have been summarised in the Nomina Nova (v)Dacrydium bidwillii Halocarpus bidwillii series published in the New Zealand Journal of Botany (Edgar Dacrydium bijorme Halocarpus bijormis 1971, Edgar and Connor 1978, 1983) and are included in re- Dacrydium kirkii Halocarpus kirkii cent books on New Zealand plants ie.g. Eagle 1982, Wilson (vi)Dacydium colensoi Lagarostrobos colensoi 1982). A number of these name changes affect important (vii)Dacrydium intermediurn Lepidothamnus intermedius forest plants and as several of these new names are now start- Dacrydium laxijolium Lepidotbamnus laxijolius ing to appear in the scientific literature, a list of changes af- (viii)Phyllocladus trichomanoidi~(unchanged) fecting tree and shrub taxa are given here. As a large number Phyllocladus glaucus (unchanged) of the readers of New Zealand Forestry are likely to use Poole Phyllocladus alpinus Phyllocladus aspleniijolius and Adams' "Trees and Shrubs of New Zealand" as their var. alpinus* * main reference for New Zealand forest plants, all the name changes are related to the fourth impression of this book. * It has been suggested that the Colenso name P, cunnin- it is important to realise that not all botanists necessarily ghamii (1884)should take precedence over the later (18891 ark agree with one particular name and you are not obliged to use name (P. -

Catalogue of Conifers

Archived Document Corporate Services, University of Exeter Welcome to the Index of Coniferaes Foreword The University is fortunate in possessing a valuable collection of trees on its main estate. The trees are planted in the grounds of Streatham Hall which was presented in 1922 to the then University college of the South West by the late Alderman W. H. Reed of Exeter. The Arboretum was begun by the original owner of Streatham Hall, R. Thornton West, who employed the firm of Veitches of Exeter and London to plant a very remarkable collection of trees. The collection is being added to as suitable material becomes available and the development of the Estate is being so planned as not to destroy the existing trees. The present document deals with the Conifer species in the collection and gives brief notes which may be of interest to visitors. It makes no pretence of being more than a catalogue. The University welcomes interested visitors and a plan of the relevant portion of the Estate is given to indicate the location of the specimens. From an original printed by James Townsend and Sons Ltd, Price 1/- Date unknown Page 1 of 34 www.exeter.ac.uk/corporateservices Archived Document Corporate Services, University of Exeter Table of Contents The letters P, S, etc., refer to the section of the Estate in which the trees are growing. (Bot. indicates that the specimens are in the garden of the Department of Botany.) Here's a plan of the estate. The Coniferaes are divided into five families - each of which is represented by one or more genera in the collection. -

JUDD W.S. Et. Al. (2002) Plant Systematics: a Phylogenetic Approach. Chapter 7. an Overview of Green

UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS An Overview of Green Plant Phylogeny he word plant is commonly used to refer to any auto- trophic eukaryotic organism capable of converting light energy into chemical energy via the process of photosynthe- sis. More specifically, these organisms produce carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water in the presence of chlorophyll inside of organelles called chloroplasts. Sometimes the term plant is extended to include autotrophic prokaryotic forms, especially the (eu)bacterial lineage known as the cyanobacteria (or blue- green algae). Many traditional botany textbooks even include the fungi, which differ dramatically in being heterotrophic eukaryotic organisms that enzymatically break down living or dead organic material and then absorb the simpler products. Fungi appear to be more closely related to animals, another lineage of heterotrophs characterized by eating other organisms and digesting them inter- nally. In this chapter we first briefly discuss the origin and evolution of several separately evolved plant lineages, both to acquaint you with these important branches of the tree of life and to help put the green plant lineage in broad phylogenetic perspective. We then focus attention on the evolution of green plants, emphasizing sev- eral critical transitions. Specifically, we concentrate on the origins of land plants (embryophytes), of vascular plants (tracheophytes), of 1 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS 2 CHAPTER SEVEN seed plants (spermatophytes), and of flowering plants dons.” In some cases it is possible to abandon such (angiosperms). names entirely, but in others it is tempting to retain Although knowledge of fossil plants is critical to a them, either as common names for certain forms of orga- deep understanding of each of these shifts and some key nization (e.g., the “bryophytic” life cycle), or to refer to a fossils are mentioned, much of our discussion focuses on clade (e.g., applying “gymnosperms” to a hypothesized extant groups. -

South East 154 October 2019.Pdf

Australian Plants Society South East NSW Group Newsletter 154 October 2019 Corymbia maculata Spotted Gum and Contac ts: President, Dianne Clark, [email protected] Macrozamia communis Burrawang Secretary, Paul Hattersley [email protected] Newsletter editor, John Knight, [email protected] Group contact [email protected] Next Meeting Saturday 2nd November 2019 Plants and Vegetation of Montague Island At ERBG Staff Meeting Room 10am Paul Hattersley, APS Member and also a Volunteer Guide for Montague Island, had originally proposed to lead a tour onto the island to discuss relevant conservation issues. However, as insufficient members expressed interest in taking the boat trip, this had to be cancelled, and likewise therefore, the planned activities at Narooma. Plans for our next meeting have now changed and we will meet at ERBG staff meeting room at 10am for morning tea, followed by a presentation by Paul at 10.30am: "The plants and vegetation of Montague Island, seabird conservation, and the impacts of weeds and other human disturbance and activity". The history and heritage of Montague Island, including the light station, will also be weaved into the talk. Paul apologises to those who wanted to join the field trip on Montague Island, but with low numbers the economics of hiring the boat proved unviable. Following Paul’s presentation, we will conduct the Show and Tell session (please bring your garden plants in flower) and after lunch, open discussion, end of year notices, and a walk at gardens to see what has happened over the past 12 months. Members might consider dining at the Chefs Cap Café, recently opened in its new location by the lakeside. -

System Klasyfikacji Organizmów

1 SYSTEM KLASYFIKACJI ORGANIZMÓW Nie ma dziś ogólnie przyjętego systemu klasyfikacji organizmów. Nie udaje się osiągnąć zgodności nie tylko w odniesieniu do zakresów i rang poszczególnych taksonów, ale nawet co do zasad metodologicznych, na których klasyfikacja powinna być oparta. Zespołowe dzieła przeglądowe z reguły prezentują odmienne i wzajemnie sprzeczne podejścia poszczególnych autorów, bez nadziei na consensus. Nie ma więc mowy o skompilowaniu jednolitego schematu klasyfikacji z literatury i system przedstawiony poniżej nie daje nadziei na zaakceptowanie przez kogokolwiek poza kompilatorem. Przygotowany został w oparciu o kilka zasad (skądinąd bardzo kontrowersyjnych): (1) Identyfikowanie ga- tunków i ich klasyfikowanie w jednostki rodzajowe, rodzinowe czy rzędy jest zadaniem specjalistów i bez szcze- gółowych samodzielnych studiów nie można kwestionować wyników takich badań. (2) Podział świata żywego na królestwa, typy, gromady i rzędy jest natomiast domeną ewolucjonistów i dydaktyków. Powody, które posłużyły do wydzielenia jednostek powinny być jasno przedstawialne i zrozumiałe również dla niespecjalistów, albowiem (3) podstawowym zadaniem systematyki jest ułatwianie laikom i początkującym badaczom poruszanie się w obezwładniającej złożoności świata żywego. Wątpliwe jednak, by wystarczyło to do stworzenia zadowalającej klasyfikacji. W takiej sytuacji można jedynie przypomnieć, że lepszy ułomny system, niż żaden. Królestwo PROKARYOTA Chatton, 1938 DNA wyłącznie w postaci kolistej (genoforów), transkrypcja nie rozdzielona przestrzennie od translacji – rybosomy w tym samym przedzia- le komórki, co DNA. Oddział CYANOPHYTA Smith, 1938 (Myxophyta Cohn, 1875, Cyanobacteria Stanier, 1973) Stosunkowo duże komórki, dwuwarstwowa błona (Gram-ujemne), wewnętrzna warstwa mureinowa. Klasa CYANOPHYCEAE Sachs, 1874 Rząd Stigonematales Geitler, 1925; zigen – dziś Chlorofil a na pojedynczych tylakoidach. Nitkowate, rozgałęziające się, cytoplazmatyczne połączenia mię- Rząd Chroococcales Wettstein, 1924; 2,1 Ga – dziś dzy komórkami, miewają heterocysty. -

Pollination Drop in Relation to Cone Morphology in Podocarpaceae: a Novel Reproductive Mechanism Author(S): P

Pollination Drop in Relation to Cone Morphology in Podocarpaceae: A Novel Reproductive Mechanism Author(s): P. B. Tomlinson, J. E. Braggins, J. A. Rattenbury Source: American Journal of Botany, Vol. 78, No. 9 (Sep., 1991), pp. 1289-1303 Published by: Botanical Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2444932 . Accessed: 23/08/2011 15:47 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Botanical Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Botany. http://www.jstor.org AmericanJournal of Botany 78(9): 1289-1303. 1991. POLLINATION DROP IN RELATION TO CONE MORPHOLOGY IN PODOCARPACEAE: A NOVEL REPRODUCTIVE MECHANISM' P. B. TOMLINSON,2'4 J. E. BRAGGINS,3 AND J. A. RATTENBURY3 2HarvardForest, Petersham, Massachusetts 01366; and 3Departmentof Botany, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand Observationof ovulatecones at thetime of pollinationin the southernconiferous family Podocarpaceaedemonstrates a distinctivemethod of pollencapture, involving an extended pollinationdrop. Ovules in all generaof the family are orthotropousand singlewithin the axil of each fertilebract. In Microstrobusand Phyllocladusovules are-erect (i.e., the micropyle directedaway from the cone axis) and are notassociated with an ovule-supportingstructure (epimatium).Pollen in thesetwo genera must land directly on thepollination drop in theway usualfor gymnosperms, as observed in Phyllocladus.In all othergenera, the ovule is inverted (i.e., the micropyleis directedtoward the cone axis) and supportedby a specializedovule- supportingstructure (epimatium). -

Ecological Sorting of Vascular Plant Classes During the Paleozoic Evolutionary Radiation

i1 Ecological Sorting of Vascular Plant Classes During the Paleozoic Evolutionary Radiation William A. DiMichele, William E. Stein, and Richard M. Bateman DiMichele, W.A., Stein, W.E., and Bateman, R.M. 2001. Ecological sorting of vascular plant classes during the Paleozoic evolutionary radiation. In: W.D. Allmon and D.J. Bottjer, eds. Evolutionary Paleoecology: The Ecological Context of Macroevolutionary Change. Columbia University Press, New York. pp. 285-335 THE DISTINCTIVE BODY PLANS of vascular plants (lycopsids, ferns, sphenopsids, seed plants), corresponding roughly to traditional Linnean classes, originated in a radiation that began in the late Middle Devonian and ended in the Early Carboniferous. This relatively brief radiation followed a long period in the Silurian and Early Devonian during wrhich morphological complexity accrued slowly and preceded evolutionary diversifications con- fined within major body-plan themes during the Carboniferous. During the Middle Devonian-Early Carboniferous morphological radiation, the major class-level clades also became differentiated ecologically: Lycopsids were cen- tered in wetlands, seed plants in terra firma environments, sphenopsids in aggradational habitats, and ferns in disturbed environments. The strong con- gruence of phylogenetic pattern, morphological differentiation, and clade- level ecological distributions characterizes plant ecological and evolutionary dynamics throughout much of the late Paleozoic. In this study, we explore the phylogenetic relationships and realized ecomorphospace of reconstructed whole plants (or composite whole plants), representing each of the major body-plan clades, and examine the degree of overlap of these patterns with each other and with patterns of environmental distribution. We conclude that 285 286 EVOLUTIONARY PALEOECOLOGY ecological incumbency was a major factor circumscribing and channeling the course of early diversification events: events that profoundly affected the structure and composition of modern plant communities. -

Fundamentals of Palaeobotany Fundamentals of Palaeobotany

Fundamentals of Palaeobotany Fundamentals of Palaeobotany cuGU .叮 v FimditLU'φL-EjAA ρummmm 吋 eαymGfr 伊拉ddd仇側向iep M d、 況 O C O W Illustrations by the author uc削 ∞叩N Nn凹創 刊,叫MH h 咀 可 白 a aEE-- EEA First published in 1987 by Chapman αndHallLtd 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Published in the USA by Chα~pman and H all 29 West 35th Street: New Yo地 NY 10001 。 1987 S. V. M秒len Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1987 ISBN-13: 978-94-010-7916-7 e-ISBN-13: 978-94-009-3151-0 DO1: 10.1007/978-94-009-3151-0 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted, or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Mey凹, Sergei V. Fundamentals of palaeobotany. 1. Palaeobotany I. Title 11. Osnovy paleobotaniki. English 561 QE905 Library 01 Congress Catα loging in Publication Data Mey凹, Sergei Viktorovich. Fundamentals of palaeobotany. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Paleobotany. I. Title. QE904.AIM45 561 8ι13000 Contents Foreword page xi Introduction xvii Acknowledgements xx Abbreviations xxi 1. Preservation 抄'pes αnd techniques of study of fossil plants 1 2. Principles of typology and of nomenclature of fossil plants 5 Parataxa and eutaxa S Taxa and characters 8 Peculiarity of the taxonomy and nomenclature of fossil plants 11 The binary (dual) system of fossil plants 12 The reasons for the inflation of generic na,mes 13 The species problem in palaeobotany lS The polytypic concept of the species 17 Assemblage-genera and assemblage-species 17 The cladistic methods 18 3. -

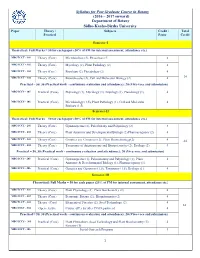

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 Onward)

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 onward) Department of Botany Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University Paper Theory / Subjects Credit / Total Practical Paper Credit Semester-I Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 101 Theory (Core) Microbiology (2), Phycology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 102 Theory (Core) Mycology (2), Plant Pathology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 103 Theory (Core) Bryology (2), Pteridology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 104 Theory (Core) Biomolecules (2), Cell and Molecular Biology (2) 4 24 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 105 Practical (Core) Phycology (1), Mycology (1), Bryology (1), Pteridology (1). 4 MBOTCCS - 106 Practical (Core) Microbiology (1.5), Plant Pathology (1), Cell and Molecular 4 Biology (1.5). Semester-II Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 201 Theory (Core) Gymnosperms (2), Paleobotany and Palynology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 202 Theory (Core) Plant Anatomy and Developmental Biology (2) Pharmacognosy (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 203 Theory (Core) Genetics and Genomics (2), Plant Biotechnology(2) 4 24 MBOTCCT - 204 Theory (Core) Taxonomy of Angiosperms and Biosystematics (2), Ecology (2) 4 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 205 Practical (Core) Gymnosperms (1), Palaeobotany and Palynology (1), Plant 4 Anatomy & Developmental Biology (1), Pharmacognosy (1). MBOTCCS - 206 Practical (Core) Genetics and Genomics (1.5), Taxonomy (1.5), Ecology (1). 4 Semester-III Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 301 Theory (Core) Plant Physiology (2), Plant Biochemistry (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 302 Theory (Core) Economic Botany (2), Bioinformatics (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 303 Theory (Core) Elements of Forestry (2), Seed Technology (2). -

Syllabus M.Sc. Botany (Choice Based Credit System)

Syllabus M.Sc. Botany (Choice Based Credit System) (To be implemented from the Academic Year 2017-18) DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY UNIVERSITY OF ALLAHABAD Page 1 of 21 DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY UNIVERSITY OF ALLAHABAD M.Sc. Syllabus (Choice Based Credit System) (To be implemented from the Academic Year 2017-18) Semester – I Course Code Marks Course Title Credits BOT501 100 Phycology and Limnology 3 BOT502 100 Mycology and Plant Pathology 3 BOT503 100 Bryology and Pteridology 3 BOT504 100 Gymnosperm and Palaeobotany 3 BOT531 100 Lab Work I (based on Course BOT501 and BOT502) 4 (Excursion/field work/ Project) BOT532 100 Lab Work II (based on Course BOT503 and BOT504) 4 (Excursion/field work/Project) Total credits 20 Semester – II Course Code Marks Course Title Credits BOT505 100 Plant Morphology and Anatomy 3 BOT506 100 Reproductive Biology, Morphogenesis and Tissue culture 3 BOT507 100 Taxonomy of Angiosperm and Economic Botany 3 BOT508 100 Ecology and Phytogeography 3 BOT533 100 Lab Work III (based on Course BOT505 and BOT506) 4 (Field work/ Project) BOT534 100 Lab Work IV (based on Course BOT507 and BOT508) 4 (Field work/ Project) Total credits 20 Semester – III Course Code Marks Course Title Credits BOT601 100 Plant Physiology 3 BOT602 100 Plant Biochemistry and Biochemical Techniques 3 BOT603 100 Cytogenetics, Plant Breeding and Biostatistics 3 BOT604 100 Microbiology 3 BOT631 100 Lab Work V (based on Course BOT601 and BOT602) 4 BOT632 100 Lab Work VI (based on Course BOT603 and BOT604) 4 Total credits 20 Semester – IV Course Code Marks Course -

CPY Document

CHAPTER 1 Plant diversity has evolved and is evolving on the earth today according to the processes of natural selection. All basic "body plans" of vascular plants were in existence by the Early Carboniferous, approximately 340 million years ago, and each major radiation occupied a particular habitat type, for example, wetland versus terra firma, pristine versus disturbed environments. Today the great spe- cies diversity we see on theplanetis dominated by just a few of these hasicplant types. This chapter sets the stage to understanding the origin and radiation of plant diversity on the earth before the significant influence of humans. The im- plication is that plants may become more diverse in the number of species level over time, but less diverse in overall form. The history of life tells us that plants that are dominant and diverse today will certainly be inconspicuous or even ex--' tinct in the distant future. EVOLUTION OF LAND PLANT DIVERSITY MAJOR INNOVATIONS AND LINEAGES THROUGH TIME William A. DiMichele and Richard M. Bateman PLANT DIVERSITY VIEWED through the lens of deep time takes on a con- siderably different aspect than when examined in the present. Although the fossil record captures only fragments of the terrestrial world of the past 450 million years, it does indicate clearly that the world of today is simply a passing phase, the latest permutation in a string of spasmodic changes in the ecological organization of the terrestrial biosphere. The pace of change in species diversity and that of ecosystem structure and composition have followed broadly parallel paths, unquestionably related but not always changing in unison.