Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allocutive Marking and the Theory of Agreement

Allocutive marking and the theory of agreement SyntaxLab, University of Cambridge, November 5th, 2019 Thomas McFadden Leibniz-Zentrum Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft (ZAS), Berlin [email protected] 1 Introduction In many colloquial varieties of Tamil (Dravidian; South Asia), one commonly comes across utterances of the following kind:1 (1) Naan Ãaaŋgiri vaaŋg-in-een-ŋgæ. I Jangri buy-pst-1sg.sbj-alloc ‘I bought Jangri.’2 Aside from the good news it brings, (1) is of interest because it contains two different types of agreement stacked on top of each other. 1. -een marks quite normal agreement with with the 1sg subject. 2. -ŋgæ marks something far less common: so-called allocutive agreement. + Rather than cross-referencing properties of one of the arguments of the main predicate, allocuative agreement provides information about the addressee. + The addition of -ŋgæ specifically indicates a plural addressee or a singular one who the speaker uses polite forms of address with. + If the addressee is a single familiar person, the suffix is simply lacking, as in (2). (2) Naan Ãaaŋgiri vaaŋg-in-een. I Jangri buy-pst-1sg.sbj ‘I bought Jangri.’ Allocutive agreement (henceforth AllAgr) has been identified in a handful of languages and is characterized by the following properties (see Antonov, 2015, for an initial typological overview): • It marks properties (gender, politeness. ) of the addressee of the current speech context. • It is crucially not limited to cases where the addressee is an argument of the local predicate. • It involves the use of grammaticalized morphological markers in the verbal or clausal inflectional system, thus is distinct from special vocative forms like English ma’am or sir. -

Linguistics 203 - Languages of the World Language Study Guide

Linguistics 203 - Languages of the World Language Study Guide This exam may consist of anything discussed on or after October 20. Be sure to check out the slides on the class webpage for this date onward, as well as the syntax/morphology language notes. This guide discusses the aspects of specific languages we looked at, and you will want to look at the notes of specific languages in the ‘language notes: syntax/morphology’ section of the webpage for examples and basic explanations. This guide does not discuss the linguistic topics we discussed in a more general sense (i.e. where we didn’t focus on a specific language), but you are expected to understand these area as well. On the webpage, these areas are found in the ‘lecture notes/slides’ section. As you study, keep in mind that there are a number of ways I might pose a question to test your knowledge. If you understand the concept, you should be able to answer any of them. These include: Definitional If a language is considered an ergative-absolutive language, what does this mean? Contrastive (definitional) Explain how an ergative-absolutive language differs from a nominative- accusative language. Identificational (which may include a definitional question as well...) Looking at the example below, identify whether language A is an ergative- absolutive language or a nominative accusative language. How do you know? (example) Contrastive (identificational) Below are examples from two different languages. In terms of case marking, how is language A different from language B? (ex. of ergative-absolutive language) (ex. of nominative-accusative language) True / False question T F Basque is an ergative-absolutive language. -

Honorificity, Indexicality and Their Interaction in Magahi

SPEAKER AND ADDRESSEE IN NATURAL LANGUAGE: HONORIFICITY, INDEXICALITY AND THEIR INTERACTION IN MAGAHI BY DEEPAK ALOK A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Linguistics Written under the direction of Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Speaker and Addressee in Natural Language: Honorificity, Indexicality and their Interaction in Magahi By Deepak Alok Dissertation Director: Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal Natural language uses first and second person pronouns to refer to the speaker and addressee. This dissertation takes as its starting point the view that speaker and addressee are also implicated in sentences that do not have such pronouns (Speas and Tenny 2003). It investigates two linguistic phenomena: honorification and indexical shift, and the interactions between them, andshow that these discourse participants have an important role to play. The investigation is based on Magahi, an Eastern Indo-Aryan language spoken mainly in the state of Bihar (India), where these phenomena manifest themselves in ways not previously attested in the literature. The phenomena are analyzed based on the native speaker judgements of the author along with judgements of one more native speaker, and sometimes with others as the occasion has presented itself. Magahi shows a rich honorification system (the encoding of “social status” in grammar) along several interrelated dimensions. Not only 2nd person pronouns but 3rd person pronouns also morphologically mark the honorificity of the referent with respect to the speaker. -

Dative (First) Complements in Basque

Dative (first) complements in Basque BEATRIZ FERNÁNDEZ JON ORTIZ DE URBINA Abstract This article examines dative complements of unergative verbs in Basque, i.e., dative arguments of morphologically “transitive” verbs, which, unlike ditransitives, do not co-occur with a canonical object complement. We will claim that such arguments fall under two different types, each of which involves a different type of non-structural licensing of the dative case. The presence of two different types of dative case in these constructions is correlated with the two different types of complement case alternations which many of these predicates exhibit, so that alternation patterns will provide us with clues to identify different sources for the dative marking. In particular, we will examine datives alternating with absolutives (i.e., with the regular object structural case in an ergative language) and datives alternating with postpositional phrases. We will first examine an approach to the former which relies on current proposals that identify a low applicative head as case licenser. Such approach, while accounting for the dative case, raises a number of issues with respect to the absolutive variant. As for datives alternating with postpositional phrases, we claim that they are lexically licensed by the lower verbal head V. Keywords Dative, conflation, lexical case, inherent case, case alternations 1. Preliminaries: bivalent unergatives Bivalent unergatives, i.e., unergatives with a dative complement, have remained largely ignored in traditional Basque studies, perhaps due to the Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 11-1 (2012), 83-98 ISSN 1645-4537 84 Beatriz Fernández & Jon Ortiz de Urbina identity of their morphological patterns of case marking and agreement with those of ditransitive configurations. -

Inferential-Realizational Morphology and Affix Ordering: Evidence from the Agreement Patterns of Basque Auxiliary Verbs

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Linguistics Linguistics 2014 INFERENTIAL-REALIZATIONAL MORPHOLOGY AND AFFIX ORDERING: EVIDENCE FROM THE AGREEMENT PATTERNS OF BASQUE AUXILIARY VERBS Parker Brody University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brody, Parker, "INFERENTIAL-REALIZATIONAL MORPHOLOGY AND AFFIX ORDERING: EVIDENCE FROM THE AGREEMENT PATTERNS OF BASQUE AUXILIARY VERBS" (2014). Theses and Dissertations-- Linguistics. 2. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/ltt_etds/2 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Linguistics at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Linguistics by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Mismatches in Honorificity Across Allocutive Languages

Mismatches in honorificity across allocutive languages Gurmeet Kaur, Göttingen Akitaka Yamada, Osaka [email protected] [email protected] Symposium: The features of allocutivity, honorifics and social relation @ LSA 2021 1 Introduction • Allocutivity is a phenomenon, where certain languages have distinct verbal morphology that encodes the addressee of the speech act (Oyharçabal, 1993; Miyagawa, 2012; Antonov, 2015; McFadden, 2020; Kaur, 2017; 2020a; 2020b; Haddican, 2018; Alok and Baker, 2018; Yamada, 2019b; Alok, 2020 etc.) • A classic example comes from Basque. (1) a. Pette-k lan egin di-k Peter-ERG work do.PFV 3ERG-M ‘Peter worked.’ (said to a male friend) b. Pette-k lan egin di-n Peter-ERG work do.PFV 3ERG-F ‘Peter worked.’ (said to a female friend) (Oyharçabal, 1993: 92-93) • As existing documentation shows, allocutive forms may or may not interact with 2nd person arguments in the clause. • This divides allocutive languages into two groups: • Group 1 disallows allocutivity with agreeing 2nd person arguments (Basque, Tamil, Magahi, Punjabi). In the absence of phi-agreement, Group 2 (Korean, Japanese) does not restrict allocutivity with any 2nd person arguments. (2) Punjabi a. tusii raam-nuu bulaa raye so (*je) 2pl.nom Ram-DOM call prog.m.hon be.pst.2pl alloc.pl ‘You were calling Ram.’ b. raam twaa-nuu bulaa reyaa sii je Ram.nom 2pl.obl-DOM call prog.m.sg be.pst.3sg alloc.pl ‘Ram was calling you.’ 1 (3) Japanese a. anata-wa ramu-o yon-dei-masi-ta. 2hon-TOP Ram-ACC call-PRG-HONA-PST ‘You were calling Ram.’ b. -

A Preliminary Study for Building the Basque Propbank

A Preliminary Study for Building the Basque PropBank Eneko Agirre, Izaskun Aldezabal, Jone Etxeberria, Eli Pociello* IXA NLP Group 649 pk. 20.080 – Donostia. Basque Country [email protected] Abstract This paper presents a methodology for adding a layer of semantic annotation to a syntactically annotated corpus of Basque (EPEC), in terms of semantic roles. The proposal we make here is the combination of three resources: the model used in the PropBank project (Palmer et al., 2005), an in-house database with syntactic/semantic subcategorization frames for Basque verbs (Aldezabal, 2004) and the Basque dependency treebank (Aduriz et al., 2003). In order to validate the methodology and to confirm whether the PropBank model is suitable for Basque and our treebank design, we have built lexical entries and labelled all argument and adjuncts occurring in our treebank for 3 Basque verbs. The result of this study has been very positive, and has produced a methodology adapted to the characteristics of the language and the Basque dependency treebank. Another goal of this study was to study whether semi-automatic tagging was possible. The idea is to present the human taggers a pre-tagged version of the corpus. We have seen that many arguments could be automatically tagged with high precision, given only the verbal entries for the verbs and a handful of examples. 2. The organization of the lexicon is similar to our 1. Introduction database of verbal models. The study* we present here is the continuation of work 3. Given the VerbNet lexicon and the annotations in developed in the Ixa1 research group, which involved the PropBank many implicit decisions according development of lexical databases and hand-tagged corpora problematic issues like the distinctions between with morphological information (Agirre et al., 1992, arguments and adjuncts are settled by example, and Aduriz et al., 1994), as well as syntactic information seem therefore easy to replicate when we tag the (Aduriz et al., 1998, Aranzabe et al., 2003). -

Sentence Negation in Basque

".' ; Sentence negation in Basque ITZIAR LAKA (M.I.T.) This paper presents an analysis of sentence negation in Basque!. Basque negative sentences show a differentpattern from non-negative ones with respect to the placement of the inflected verb. This particular pattern displays an interesting asymmetry depending on the clause type. The phenomena are explained in terms of head movement. The negative particle ez 'not' is analyzed as a head, in the spirit of Pollock (1989). This head takes IP as its complement and projects a Neg Phrase. At S-struc ture, INFL adjoins to negation; the fact that negation is initial unlike the rest of the heads in Basque creates the 'dislocated' pattern of matrix sentence negation. In embedded clauses, the complex [NEGATION/INFL] adjoins to CaMP, which is final. This latter movement is the source of the asymmetry between matrix and embedded sentence negation. The paper also explores grammatical constraints on sentence negation in natural languages. It is argued that Negative Polarity ltems(NPI) are licensed by negation under c-command at S-structure, and that sentence negation must be c-commanded by Tense also at S-structure. The first condition is shown to account for NPI licensing by negation in Basque and English. The second condition which is named the Tense C-command Condition (TCC) is proposed based mainly on evidence from Basque. Some cross-lin guistic evidence is shown to support the hypothesis as universal. The paper is organized as follows: The first section presents some general properties of Basque grammar relevant for the analysis. The second section describes the phenomena induced by negation both in matrix and embedded clauses. -

Lexical Causatives and Causative Alternation in Basque

LEXICAL CAUSATIVES AND CAUSATIVE ALTERNATION IN BASQUE B.Oyhan;:abal (IKER-UMR 5478, CNRS) Abstract After offering a brief survey of the features of causative sentences in Basque, mainly on the basis of Dixon's (2000) criteria, the paper deals with Basque lexical causatives, which can be used as either causative or unaccusative verbs. The proposed analysis assumes that lexical decomposition is carried out directly according to syntactic principles (Hale & Keyser 1993, Baker 1997, McGinnis 2000), and that different types of causative sentence (morphological vs lexical causatives) correspond to different types ofphrase (VoiceP vs VP) selected by the Cause head (Pylkkiinnen 2001, 2002; Meggerdoomian 2002). The paper shows that in Basque lexical causatives the Cause head selects one of the predicates BECOME or GO only. Other intransitive verbs are excluded from lexical causativization, even those which are superficially similar verbs of change because they are absolutive monadic verbs (reflexive verbs like orraztu 'comb: verbs ofhappening like gertatu 'happen: or verbs ofactivity like jostatu 'play,). Three types oflexical causative are distinguished and analyzed following lexical decomposition: verbs ofchange of (physical) state, verbs ofchange ofplace and psychological causatives. Since Basque, unlike Finnish or japanese, shows a strict correlation between causation and the existence ofan external argument, it is assumed that in Basque as in English, the Cause and Voice heads conjlate in lexical causatives (Pylkiinnen 2002). There are two main ways to form causative verbs in Basque, illustrated in (2a) and (2b):1 1 Abbrevations. ABS: absolutive, ART: article, AUX: auxiliary, CAU: causative, COM: comitative, DAT: dative, ERG: ergative, FOC: focus marker, FUT: future, IMP: imperfective, INE: inesive, INS: instrumental, INTER: interrogative, PL: plural, PAR: partitive, PTP: participle, RFL: reflexive. -

The Category of Number in Basque: I

The category of number in Basque: I. Synchronic and historical aspects Mikel Mart´ınez To cite this version: Mikel Mart´ınez.The category of number in Basque: I. Synchronic and historical aspects. The category of number in Basque: I. Synchronic and historical aspects, 2009, pp.36. <artxibo- 00528568> HAL Id: artxibo-00528568 https://artxiker.ccsd.cnrs.fr/artxibo-00528568 Submitted on 22 Oct 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. 03_Martinez:Maquetación 1 4/11/09 12:39 Página 63 The category of number in Basque: I. Synchronic and historical aspects MIKEL MARTÍNEZ ARETA * 0. INTRODUCTION 1 his article, which is divided into two parts, is an attempt to discuss the Tpresent, the history and the proto-history of the category of grammati - cal number in Basque. The first is published in this volume of Fontes Linguae Vasconum , and the second will be published in the following volume. The organization of the paper will be as follows. In point 1 (in this vol- ume), I describe how the category of number works in contemporary stan - dard Basque, with some limited references to (also contemporary) dialectal peculiarities. -

Assertions and Judgements, Epistemics, and Evidentials 1

Assertions and Judgements, Epistemics, and Evidentials Manfred Krifka1 Leibniz-Zentrum Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft & Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin [email protected] Workshop 'Speech Acts: Meanings, Uses, Syntactic and Prosodic Realizations' Leibniz-ZAS Berlin, May 29 – 31, 2017 1. Overview Topics to be covered: • The nature of assertion as expressing commitments • Judgements as a separate act from commitments • Subjective epistemics as expressing strength of judgments • Evidentials as expressing source of judgements • Discourse epistemics 2. Assertions as Commitments 2.1 The dynamic view of assertions (1) Assertions as modifying the common ground, “a body of information that is available, or presumed to be available, as a resource for communication” (Stalnaker 1978) (2) Standard view of assertion in dynamic semantics s (Stalnaker 1978, 2002, 2014; Heim 1983, Veltman 1996) φ s+φ – Common ground is modeled by a set of propositions (context set), – Assertion of a proposition restricts the input common ground to an output common ground by intersection. + Example: s + φ = s ⋂ φ (3) Alternative view: Common ground as sets of propositions – Assertion of a proposition adds the proposition to the common ground c φ – Context set: the intersection of the propositions of the common ground + Example: c + φ = c ⋃ {φ} (4) Advantages of this view: c ⋃ {φ} – Meaningful addition of tautologies, e.g. ‘2399 is a prime number’ = – possible modeling of contradictory common grounds (would lead to empty context set) – possible enrichment by imposing -

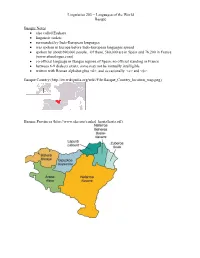

Linguistics 203 – Languages of the World Basque Basque Notes • Also

Linguistics 203 – Languages of the World Basque Basque Notes also called Euskara linguistic isolate surrounded by Indo-European languages was spoken in Europe before Indo-European languages spread spoken by about 690,000 people. Of these, 580,000 are in Spain and 76,200 in France. (www.ethnologue.com) co-official language in Basque regions of Spain; no official standing in France between 6-9 dialects exists; some may not be mutually intelligible written with Roman alphabet plus <ñ>, and occasionally > and <ü>. Basque Country (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Basque_Country_location_map.png) Basque Provinces (http://www.eke.org/euskal_herria/karta.gif) Linguistics 203 – Languages of the World Basque % fluent speakers by location (http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ac/Euskara.png) Linguistics 203 – Languages of the World Basque Phonology (phonemic) (based on Hualde & de Urbina 2003) Vowels: o canonical 5 vowel system (Gipuzkoan, High Navarrese, Standard Basque) o Zuberoan dialect additionally has /y/, and it phonemically distinguishes nasal from non-nasal vowels in word-final stressed position. Consonants: labio- apico- lamino- palato- bilabial dental palatal velar glottal dental alveolar alveolar alveolar plosive p b t d c ɟ k g aspirated {ph} {th} {kh} plosive nasal m n ɲ fricative f } } ʃ {ʒ} (x) {h/ħ} affricate tʃ flap (ɾ) trill r lateral l ʎ approximant o Sounds not in Zuberoan dialect in parentheses ( ). Sounds only in Zuberoan dialect in curly brackets {}. o Note that Basque distinguishes apical consonants from laminal ones; thus, zu [ u] ‘you’ and su u] ‘fire’. Linguistics 203 – Languages of the World Basque Syntax Basque is an ergative-absolutive language; meaning that i.