Investigating the Syntax of Speech Acts: Embedding Illocutionary Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allocutive Marking and the Theory of Agreement

Allocutive marking and the theory of agreement SyntaxLab, University of Cambridge, November 5th, 2019 Thomas McFadden Leibniz-Zentrum Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft (ZAS), Berlin [email protected] 1 Introduction In many colloquial varieties of Tamil (Dravidian; South Asia), one commonly comes across utterances of the following kind:1 (1) Naan Ãaaŋgiri vaaŋg-in-een-ŋgæ. I Jangri buy-pst-1sg.sbj-alloc ‘I bought Jangri.’2 Aside from the good news it brings, (1) is of interest because it contains two different types of agreement stacked on top of each other. 1. -een marks quite normal agreement with with the 1sg subject. 2. -ŋgæ marks something far less common: so-called allocutive agreement. + Rather than cross-referencing properties of one of the arguments of the main predicate, allocuative agreement provides information about the addressee. + The addition of -ŋgæ specifically indicates a plural addressee or a singular one who the speaker uses polite forms of address with. + If the addressee is a single familiar person, the suffix is simply lacking, as in (2). (2) Naan Ãaaŋgiri vaaŋg-in-een. I Jangri buy-pst-1sg.sbj ‘I bought Jangri.’ Allocutive agreement (henceforth AllAgr) has been identified in a handful of languages and is characterized by the following properties (see Antonov, 2015, for an initial typological overview): • It marks properties (gender, politeness. ) of the addressee of the current speech context. • It is crucially not limited to cases where the addressee is an argument of the local predicate. • It involves the use of grammaticalized morphological markers in the verbal or clausal inflectional system, thus is distinct from special vocative forms like English ma’am or sir. -

Linguistics 203 - Languages of the World Language Study Guide

Linguistics 203 - Languages of the World Language Study Guide This exam may consist of anything discussed on or after October 20. Be sure to check out the slides on the class webpage for this date onward, as well as the syntax/morphology language notes. This guide discusses the aspects of specific languages we looked at, and you will want to look at the notes of specific languages in the ‘language notes: syntax/morphology’ section of the webpage for examples and basic explanations. This guide does not discuss the linguistic topics we discussed in a more general sense (i.e. where we didn’t focus on a specific language), but you are expected to understand these area as well. On the webpage, these areas are found in the ‘lecture notes/slides’ section. As you study, keep in mind that there are a number of ways I might pose a question to test your knowledge. If you understand the concept, you should be able to answer any of them. These include: Definitional If a language is considered an ergative-absolutive language, what does this mean? Contrastive (definitional) Explain how an ergative-absolutive language differs from a nominative- accusative language. Identificational (which may include a definitional question as well...) Looking at the example below, identify whether language A is an ergative- absolutive language or a nominative accusative language. How do you know? (example) Contrastive (identificational) Below are examples from two different languages. In terms of case marking, how is language A different from language B? (ex. of ergative-absolutive language) (ex. of nominative-accusative language) True / False question T F Basque is an ergative-absolutive language. -

Performative Speech Act Verbs in Present Day English

PERFORMATIVE SPEECH ACT VERBS IN PRESENT DAY ENGLISH ELENA LÓPEZ ÁLVAREZ Universidad Complutense de Madrid RESUMEN. En esta contribución se estudian los actos performativos y su influencia en el inglés de hoy en día. A partir de las teorías de J. L. Austin, entre otros autores, se desarrolla un panorama de esta orientación de la filosofía del lenguaje de Austin. PALABRAS CLAVE. Actos performativos, enunciado performativo, inglés. ABSTRACT. This paper focuses on performative speech act verbs in present day English. Reading the theories of J. L. Austin, among others,. With the basis of authors as J. L. Austin, this paper develops a brief landscape about this orientation of Austin’s linguistic philosophy. KEY WORDS. Performative speech act verbs, performative utterance, English. 1. INTRODUCCIÓN 1.1. HISTORICAL THEORETICAL BACKGROUND 1.1.1. The beginnings: J.L. Austin The origin of performative speech acts as we know them today dates back to the William James Lectures, the linguistic-philosophical theories devised and delivered by J.L. Austin at Harvard University in 1955, and collected into a series of lectures entitled How to do things with words, posthumously published in 1962. Austin was one of the most influential philosophers of his time. In these lectures, he provided a thorough exploration of performative speech acts, which was an extremely innovative area of study in those days. In the following pages, Austin’s main ideas (together with some comments by other authors) will be presented. 1.1.1.1. Constative – performative distinction In these lectures, Austin begins by making a clear distinction between constative and performative utterances. -

Honorificity, Indexicality and Their Interaction in Magahi

SPEAKER AND ADDRESSEE IN NATURAL LANGUAGE: HONORIFICITY, INDEXICALITY AND THEIR INTERACTION IN MAGAHI BY DEEPAK ALOK A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Linguistics Written under the direction of Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Speaker and Addressee in Natural Language: Honorificity, Indexicality and their Interaction in Magahi By Deepak Alok Dissertation Director: Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal Natural language uses first and second person pronouns to refer to the speaker and addressee. This dissertation takes as its starting point the view that speaker and addressee are also implicated in sentences that do not have such pronouns (Speas and Tenny 2003). It investigates two linguistic phenomena: honorification and indexical shift, and the interactions between them, andshow that these discourse participants have an important role to play. The investigation is based on Magahi, an Eastern Indo-Aryan language spoken mainly in the state of Bihar (India), where these phenomena manifest themselves in ways not previously attested in the literature. The phenomena are analyzed based on the native speaker judgements of the author along with judgements of one more native speaker, and sometimes with others as the occasion has presented itself. Magahi shows a rich honorification system (the encoding of “social status” in grammar) along several interrelated dimensions. Not only 2nd person pronouns but 3rd person pronouns also morphologically mark the honorificity of the referent with respect to the speaker. -

Teaching Performative Verbs and Nouns in EU Maritime Regulations

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 141 ( 2014 ) 90 – 95 WCLTA 2013 Teaching Performative Verbs and Nouns in EU Maritime Regulations Silvia Molina Plaza a Technical University of Madrid, ETSIN Avda de la Victoria, 4, Madrid , 28040, Spain Abstract This paper is concerned with performative speech acts in European Union fisheries legislation with a view to relating the semantic analysis of directive and expressive speech act verbs to politeness strategies for the management of positive and negative face. The performative verbs used in directive and expressive speech acts belong to the semantic domain of communication verbs. The directive verbs occurring in the material are: appeal, authorize, call upon, conclude, invite, promise, request, urge and warn while the expressive verbs are: congratulate, express (gratitude), pay (tribute) and thank. The semantic analysis of directive verbs draws on Leech’s framework for illocutionary verbs analysis (Leech 1983: 218). The analysis suggests that the choice of directive and expressive speech act verbs and their co-occurrence with particular addressees are motivated by the socio-pragmatic situation. 30 Naval Engineering students from the UPM also learned how these speech act verbs are used in context in the subject English for Professional and Academic Communication (2011-2012). © 2014 Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license © 2014 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Selection and peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of WCLTA 2013. Selection and peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of WCLTA 2013. -

Mismatches in Honorificity Across Allocutive Languages

Mismatches in honorificity across allocutive languages Gurmeet Kaur, Göttingen Akitaka Yamada, Osaka [email protected] [email protected] Symposium: The features of allocutivity, honorifics and social relation @ LSA 2021 1 Introduction • Allocutivity is a phenomenon, where certain languages have distinct verbal morphology that encodes the addressee of the speech act (Oyharçabal, 1993; Miyagawa, 2012; Antonov, 2015; McFadden, 2020; Kaur, 2017; 2020a; 2020b; Haddican, 2018; Alok and Baker, 2018; Yamada, 2019b; Alok, 2020 etc.) • A classic example comes from Basque. (1) a. Pette-k lan egin di-k Peter-ERG work do.PFV 3ERG-M ‘Peter worked.’ (said to a male friend) b. Pette-k lan egin di-n Peter-ERG work do.PFV 3ERG-F ‘Peter worked.’ (said to a female friend) (Oyharçabal, 1993: 92-93) • As existing documentation shows, allocutive forms may or may not interact with 2nd person arguments in the clause. • This divides allocutive languages into two groups: • Group 1 disallows allocutivity with agreeing 2nd person arguments (Basque, Tamil, Magahi, Punjabi). In the absence of phi-agreement, Group 2 (Korean, Japanese) does not restrict allocutivity with any 2nd person arguments. (2) Punjabi a. tusii raam-nuu bulaa raye so (*je) 2pl.nom Ram-DOM call prog.m.hon be.pst.2pl alloc.pl ‘You were calling Ram.’ b. raam twaa-nuu bulaa reyaa sii je Ram.nom 2pl.obl-DOM call prog.m.sg be.pst.3sg alloc.pl ‘Ram was calling you.’ 1 (3) Japanese a. anata-wa ramu-o yon-dei-masi-ta. 2hon-TOP Ram-ACC call-PRG-HONA-PST ‘You were calling Ram.’ b. -

About Pronouns

About pronouns Halldór Ármann Sigurðsson Lund University Abstract This essay claims that pronouns are constructed as syntactic relations rather than as discrete feature bundles or items. The discussion is set within the framework of a minimalist Context-linked Grammar, where phases contain silent but active edge features, edge linkers, including speaker and hearer features. An NP is phi- computed in relation to these linkers, the so established relation being input to context scanning (yielding reference). Essentially, syntax must see to it that event participant roles link to speech act roles, by participant linking (a subcase of context linking, a central computational property of natural language). Edge linkers are syntactic features–not operators–and can be shifted, as in indexical shift and other Kaplanian monster phenomena, commonly under control. The essay also develops a new analysis of inclusiveness and of the different status of different phi-features in grammar. The approach pursued differs from Distributed Morphology in drawing a sharp line between (internal) syntax and (PF) externalization, syntax constructing relations–the externalization process building and expressing items. Keywords: Edge linkers, pronouns, speaker, phi-features, context linking, context scanning, indexical shift, inclusiveness, bound variables 1. Introduction* Indexical or deictic items include personal pronouns (I, you, she, etc.), demonstrative pronouns (this, that, etc.), and certain local and temporal adverbials and adjectives (here, now, presently, etc.). In the influential Kaplanian approach (Kaplan 1989), indexicals are assumed to have a fixed reference in a fixed context of a specific speech act or speech event. Schlenker (2003:29) refers to this leading idea as the fixity thesis, stating it as follows: Fixity Thesis (a corollary of Direct Reference): The semantic value of an indexical is fixed solely by the context of the actual speech act, and cannot be affected by any logical operators. -

Performative Sentences and the Morphosyntax-Semantics Interface in Archaic Vedic

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Journal of South Asian Linguistics JSAL volume 1, issue 1 October 2008 Performative Sentences and the Morphosyntax-Semantics Interface in Archaic Vedic Eystein Dahl, University of Oslo Received November 1, 2007; Revised October 15, 2008 Abstract Performative sentences represent a particularly intriguing type of self-referring assertive clauses, as they constitute an area of linguistics where the relationship between the semantic-grammatical and the pragmatic-contextual dimension of language is especially transparent. This paper examines how the notion of performativity interacts with different tense, aspect and mood categories in Vedic. The claim is that one may distinguish three slightly different constraints on performative sentences, a modal constraint demanding that the proposition is represented as being in full accordance with the Common Ground, an aspectual constraint demanding that there is a coextension relation between event time and reference time and a temporal constraint demanding that the reference time is coextensive with speech time. It is shown that the Archaic Vedic present indicative, aorist indicative and aorist injunctive are quite compatible with these constraints, that the basic modal specifications of present and aorist subjunctive and optative violate the modal constraint on performative sentences, but give rise to speaker-oriented readings which in turn are compatible with that constraint. However, the imperfect, the present injunctive, the perfect indicative and the various modal categories of the perfect stem are argued to be incompatible with the constraints on performative sentences. 1 Introduction Performative sentences represent a particularly intriguing type of self-referring assertive clauses, as they constitute an area of linguistics where the relationship between the semantic-grammatical and the pragmatic-contextual dimension of language is especially transparent. -

Assertions and Judgements, Epistemics, and Evidentials 1

Assertions and Judgements, Epistemics, and Evidentials Manfred Krifka1 Leibniz-Zentrum Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft & Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin [email protected] Workshop 'Speech Acts: Meanings, Uses, Syntactic and Prosodic Realizations' Leibniz-ZAS Berlin, May 29 – 31, 2017 1. Overview Topics to be covered: • The nature of assertion as expressing commitments • Judgements as a separate act from commitments • Subjective epistemics as expressing strength of judgments • Evidentials as expressing source of judgements • Discourse epistemics 2. Assertions as Commitments 2.1 The dynamic view of assertions (1) Assertions as modifying the common ground, “a body of information that is available, or presumed to be available, as a resource for communication” (Stalnaker 1978) (2) Standard view of assertion in dynamic semantics s (Stalnaker 1978, 2002, 2014; Heim 1983, Veltman 1996) φ s+φ – Common ground is modeled by a set of propositions (context set), – Assertion of a proposition restricts the input common ground to an output common ground by intersection. + Example: s + φ = s ⋂ φ (3) Alternative view: Common ground as sets of propositions – Assertion of a proposition adds the proposition to the common ground c φ – Context set: the intersection of the propositions of the common ground + Example: c + φ = c ⋃ {φ} (4) Advantages of this view: c ⋃ {φ} – Meaningful addition of tautologies, e.g. ‘2399 is a prime number’ = – possible modeling of contradictory common grounds (would lead to empty context set) – possible enrichment by imposing -

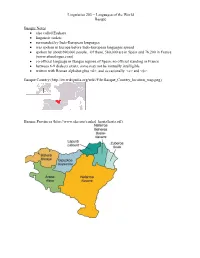

Linguistics 203 – Languages of the World Basque Basque Notes • Also

Linguistics 203 – Languages of the World Basque Basque Notes also called Euskara linguistic isolate surrounded by Indo-European languages was spoken in Europe before Indo-European languages spread spoken by about 690,000 people. Of these, 580,000 are in Spain and 76,200 in France. (www.ethnologue.com) co-official language in Basque regions of Spain; no official standing in France between 6-9 dialects exists; some may not be mutually intelligible written with Roman alphabet plus <ñ>, and occasionally > and <ü>. Basque Country (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Basque_Country_location_map.png) Basque Provinces (http://www.eke.org/euskal_herria/karta.gif) Linguistics 203 – Languages of the World Basque % fluent speakers by location (http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ac/Euskara.png) Linguistics 203 – Languages of the World Basque Phonology (phonemic) (based on Hualde & de Urbina 2003) Vowels: o canonical 5 vowel system (Gipuzkoan, High Navarrese, Standard Basque) o Zuberoan dialect additionally has /y/, and it phonemically distinguishes nasal from non-nasal vowels in word-final stressed position. Consonants: labio- apico- lamino- palato- bilabial dental palatal velar glottal dental alveolar alveolar alveolar plosive p b t d c ɟ k g aspirated {ph} {th} {kh} plosive nasal m n ɲ fricative f } } ʃ {ʒ} (x) {h/ħ} affricate tʃ flap (ɾ) trill r lateral l ʎ approximant o Sounds not in Zuberoan dialect in parentheses ( ). Sounds only in Zuberoan dialect in curly brackets {}. o Note that Basque distinguishes apical consonants from laminal ones; thus, zu [ u] ‘you’ and su u] ‘fire’. Linguistics 203 – Languages of the World Basque Syntax Basque is an ergative-absolutive language; meaning that i. -

Syntax in the Treetops

Draft Syntax in the Treetops Shigeru Miyagawa September 2020 ii Contents Preface………………………………………………………………………………...vi Abbreviations………………………………………………………………………...vii Chapter 1. Setting the Stage…………………………………………………………1 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………1 2. Ross (1970) and Emonds (1969).…...………………………………………………3 2.1 Combining Ross (1970) and Emonds (1969)…...………...…………………..11 2.2 Problems associated with the performative analysis…………...……..............12 3. Evidence for the representation of the speaker and addressee…………...………..18 3.1 Logophors………………………….………………………………...………..19 3.2 Modern evidence for the speaker and addressee representations in syntax…………………………………………..…………………..………....20 3.2.1 Allocutive agreement and the addressee representation…………...…….21 3.2.2 Evidence for the speaker representation: Romanian………………….....23 3.3 Speech Act Phrase………………………………………………………….....25 4. Problems associated with Emonds’s conception of the root……………………....27 5. Speaker and temporal coordinates (Giorgi 2010) ………………………………....34 6. SAP, Act Phrase, and Illocutionary Force………………………………………....36 7. Previewing the remaining chapters………………………………………………..46 Miyagawa, Treetops, draft, Sep2020 iii Chapter 2. The SAP and the politeness φ-feature………………………………...55 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………..55 2. Where is -mas-?…………………………………………………………………....57 3. Moving -mas- to the “correct” location…………………………………………....60 4. Allocutive agreement at C………………………………………………………....63 4.1 SAP……………………………………………………………………............69 4.2 Style adverbs in English…………………………………………………...….74 -

The Common Syntax of Deixis and Affirmation George Tsoulas University of York

Chapter 12 The common syntax of deixis and affirmation George Tsoulas University of York This paper pursues a formal analysis of the idea that affirmative answers to Yes/No questions correspond to a sort of propositional deixis whereby the relevant proposition is pointed at. The empirical case involves an analysis of the deictic particle Nà in Greek and a comparison of its syntax with that of the affirmative particle Nè. It is shown that both involve an extra head which in the case of the deictic particle is uniformly externalised as the pointing ges- ture. It is argued that gestural externalisation of syntactic structure should be considered on a par with phonetic externalisation (not only in sign languages). The grammar of the af- firmative particle gives us also an account of the observed facts about Greek whereby both the truth and the polarity answering system appear to coexist. 1 Introduction Holmberg (2015) begins thus: ‘It is certainly not obvious that expressions like Yes and No have syntactic structure.’ It is even less obvious that elements like Yes and No have complex internal syntactic and semantic structure. In the literature on the semantics of Yes/No questions an explicit semantics for Yes is rarely given. Groenendijk & Stokhof (1984) is one of these exceptions and their semantics is given in (1): (1) »»yes¼¼=λp p(a) Groenendijk & Stokhof’s (1984) syntactic assumption is that Yes and No are sentential adverbs of type S/S. It would then seem that there is not much of interest that either the semantics or the implied syntax would give us.