Trade Marks Inter Partes Decision O/008/17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2020 Prices Continue to Climb

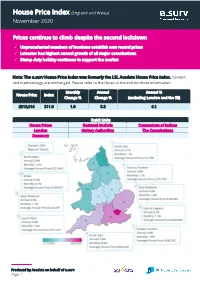

(England and Wales) House Price Index November 2020 Prices continue to climb despite the second lockdown ✓ Unprecedented numbers of locations establish new record prices ✓ Leicester has highest annual growth of all major conurbations ✓ Stamp duty holiday continues to support the market Note: The e.surv House Price Index was formerly the LSL Acadata House Price Index. Content and methodology are unchanged. Please refer to the Notes at the end for more information. Monthly Annual Annual % House Price Index Change % Change % (excluding London and the SE) £319,816 311.0 1.0 5.8 6.1 Quick Links House Prices Regional Analysis Comparison of Indices London Unitary Authorities The Conurbations Summary Produced by Acadata on behalf of e.surv Page 1 House Price Index (England and Wales) November 2020 Table 1. Average House Prices in England and Wales for the period November 2019 – November 2020 Link to source Excel Month Year House Price Index Monthly Change % Annual Change % November 2019 £302,368 294.3 0.4 1.5 December 2019 £302,886 294.6 0.2 1.5 January 2020 £304,088 295.7 0.4 1.7 February 2020 £306,012 297.6 0.6 1.9 March 2020 £305,457 297.1 -0.2 2.0 April 2020 £301,658 293.4 -1.2 1.0 May 2020 £298,672 290.5 -1.0 0.0 June 2020 £298,727 290.5 0.0 0.1 July 2020 £302,912 294.6 1.4 1.7 August 2020 £307,802 299.3 1.6 3.4 September 2020 £312,475 303.9 1.5 4.4 October 2020 £316,543 307.8 1.3 5.1 November 2020 £319,816 311.0 1.0 5.8 Note: The e.surv House Price Index provides the “average of all prices paid for domestic properties”, including those made with cash. -

Hot and Cold Seasons in the Housing Market∗

Hot and Cold Seasons in the Housing Market L. Rachel Ngai Silvana Tenreyro London School of Economics, CEP, and CEPR April 2013 Abstract Every year housing markets in the United Kingdom and the United States experience system- atic above-trend increases in both prices and transactions during the second and third quarters (the “hot season”) and below-trend falls during the fourth and first quarters (the “cold sea- son”). House price seasonality poses a challenge to existing models of the housing market. To explain seasonal patterns, this paper proposes a matching model that emphasizes the role of match-specific quality between the buyer and the house and the presence of thick-market effects in housing markets. It shows that a small, deterministic driver of seasonality can be amplified and revealed as deterministic seasonality in transactions and prices, quantitatively mimicking the seasonal fluctuations observed in the United Kingdom and the United States. Key words: housing market, thick-market effects, search-and-matching, seasonality, house price fluctuations, match quality For helpful comments, we would like to thank James Albrecht, Robert Barro, Francesco Caselli, Tom Cunningham, Morris Davis, Steve Davis, Jordi Galí, Christian Julliard, Peter Katuscak, Philipp Kircher, Nobu Kiyotaki, John Leahy, Francois Ortalo-Magné, Denise Osborn, Chris Pissarides, Richard Rogerson, Kevin Sheedy, Jaume Ventura, Randy Wright, and seminar participants at the NBER Summer Institute, SED, and various universities and central banks. For superb research assistance, we thank Jochen Mankart, Ines Moreno-de-Barreda, and Daniel Vernazza. Tenreyro acknowledges financial support from the European Research Council under the European Community’s ERC starting grant agreement 240852 Research on Economic Fluctuations and Globalization, Bank of Spain through CREI’sAssociate Professorship, and STICERD starting grant. -

Accounting for Uk Retailers' Success

THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER - APPROVED ELECTRONICALLY GENERATED THESIS/DISSERTATION COVER-PAGE Electronic identifier: 16349 Date of electronic submission: 27/09/2015 The University of Manchester makes unrestricted examined electronic theses and dissertations freely available for download and reading online via Manchester eScholar at http://www.manchester.ac.uk/escholar. This print version of my thesis/dissertation is a TRUE and ACCURATE REPRESENTATION of the electronic version submitted to the University of Manchester's institutional repository, Manchester eScholar. Approved electronically generated cover-page version 1.0 ACCOUNTING FOR UK RETAILERS’ SUCCESS: KEY METRICS FOR SUCCESS AND FAILURE A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 TARLOK N. TEJI MANCHESTER BUSINESS SCHOOL Contents LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................................... 9 LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... 10 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. 11 DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT ............................................................................................ 12 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... 13 PREFACE .................................................................................................................................. -

Experimenter's Licence for the Home-Made Set ( P. 591) SPECIAL

S g Experimenter's Licence for The Home-made Set ( p. 591) No. 26 SATURDAY, DECEMBER 2, 1922 Price 3d. Regular Regular Features Features RADIOGRAMS TELEPHONY TRANSMISSIONS 111 ON YOUR WAVE- LENGTH CLUB EVENTS la RI if 6c1 3 INFORMATION LETTERS BUREAU Photograph of a Single -circuit One -valve Set constructed by ETC.ETC. Mr. A. W. Owen, of Walthamstow si 111 SPECIAL ARTICLES Atmospherics or Statics Amateur Transmissions and the A Basket -coil Type Tuner G.P.O. Shall We Ever See by Wireless ? A Novel Utility Aerial Telephone Winding All About the Valve Loose -coupler Device Rectifying Panels for Unit Set InterferencePrevention emataitWttviess 582 DECEMBER 2, 1922 (1VIITCHELFONES ECONOMICELECTRICLTD. Are not a spasmodic production to meet A I a sudden demand, but have been on the I-1 Have YOU tried the market for over three months, and during this period 27,000 have been distributed " XTRAUDION " VALVE ? to thetrade, and consequently we have the latest and best development of not been able to offer them direct to the retail buyer. the 3 Electrode Valve. RECTIFIES, OSCILLATES 1,000per week are now available, and we announce AMPLIFIES Its Mechanical Construction DELIVERY FROM STOCK makes it a stronger and more lasting Youpostyourorder,orcallatour valve than any other. premises and get them at once.Think The Filament consumes well under what this means to you-you, perhaps, who half - an - amp. at 4 volts.Anode have been waiting and are stillwaiting. Potential, 50 volts. Standard resistance 4,000 ohms, double headgear with Its Amplifying Properties are double headstraps,comfortable,highlyefficient, wonderful and its freedom from noises and foolproof a revelation. -

Britten-Working in the Music Industry

Visit our How To website at www.howto.co.uk At www.howto.co.uk you can engage in conversation with our authors – all of whom have ‘been there and done that’ in their specialist fields. You can get access to special offers and additional content but most importantly you will be able to engage with, and become a part of, a wide and growing community of people just like yourself. At www.howto.co.uk you’ll be able to talk and share tips with people who have similar interests and are facing similar challenges in their lives. People who, just like you, have the desire to change their lives for the better – be it through moving to a new country, starting a new business, growing their own vegetables, or writing a novel. At www.howto.co.uk you’ll find the support and encourage- ment you need to help make your aspirations a reality. You can go direct to www.working-in-the-music-industry.co.uk which is part of the main How To site. How To Books strives to present authentic, inspiring, practical information in their books. Now, when you buy a title from How To Books, you get even more than just words on a page. Published by How To Content, A division of How To Books Ltd, Spring Hill House, Spring Hill Road Begbroke, Oxford OX5 1RX Tel: (01865) 375794. Fax: (01865) 379162 info_howtobooks.co.uk www.howtobooks.co.uk All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or stored in an information retrieval system (other than for the purposes of review), without the express permission of the Publisher given in writing. -

Case 14 RICHARD BRANSON and the VIRGIN GROUP of COMPANIES in 2002*

Case 14 RICHARD BRANSON AND THE VIRGIN GROUP OF COMPANIES IN 2002* Richard Branson’s 50th birthday in July 2000 had no discernable effect either on Sir Richard’s energy or the entrepreneurial vigor of his Virgin group of companies. The new millennium saw Branson’s sprawling business empire spawn yet more new ventures. These included new companies within Virgin’s existing lines of business—a new airline in Australia, retail ventures in Singapore and Thailand, and wireless telecom ventures in Asia, the US and Australia—and entirely new enterprises. A number of these new ventures involved internet-based businesses: on line sales of cars and motorcycles through Virgin Car and Virgin Bike, online auctions through Virgin Net, Virgin’s ISP and portal business. Other initiatives included acquisition of a consortium a minority stake in Britain’s air traffic control system and a (unsuccessful) bid to run Britain’s National Lottery. In May 2002, Branson was planning yet more business ventures including a wireless phone company in Japan, a low-cost airline in the US, a car rental business in Australia, and an on-line pharmacy in the UK. Yet despite Branson’s unstoppable enthusiasm for launching new business ventures, there was increasing evidence of a rising tide of financial problems within the Virgin group: ??Virgin’s Megastores and its Our Price music chains was suffering heavily from the downturn in sales of music CDs. ??All of Virgin’s travel businesses—but especially its flagship, Virgin Atlantic—were suffering from the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Even before the terrorist attack, Virgin Atlantic was incurring significant losses. -

Music Industry

Market Review 2010 Second Edition, February 2010 Edited by Katie Hughes ISBN 978-1-84729-579-8 Music Industry Music Industry Foreword In today’s competitive business environment, knowledge and understanding of your marketplace is essential. With over 25 years’ experience producing highly respected off-the-shelf publications, Key Note has built a reputation as the number one source of UK market information. Below are just a few of the comments our business partners and clients have made on Key Note’s range of reports. “The Chartered Institute of Marketing encourages the use of market research as an important part of a systematic approach to marketing. Key Note reports have been available in the Institute’s Information and Library Service for many years and have helped our members to build knowledge and understanding of their marketplace and their customers.” The Chartered Institute of Marketing “We have enjoyed a long-standing relationship with Key Note and have always received an excellent service. Key Note reports are well produced and are always in demand by users of the business library.” “Having subscribed to Market Assessment reports for a number of years, we continue to be impressed by their quality and breadth of coverage.” The British Library “Key Note reports cover a wide range of industries and markets — they are detailed, well written and easily digestible, with a good use of tables. They allow deadlines to be met by providing a true overview of a particular market and its prospects.” NatWest “Accurate and relevant market intelligence is the starting point for every campaign we undertake. -

Understanding High Street Performance

UNDERSTANDING HIGH STREET PERFORMANCE A report prepared by GENECON LLP and Partners DECEMBER 2011 Department for Business, Innovation and Skills Understanding High Street Performance December 2011 Department for Business, Innovation and Skills Understanding High Street Performance A report prepared by GENECON LLP and Partners. December 2011 Department for Business, Innovation and Skills Understanding High Street Performance December 2011 Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Study purpose 1 1.2 An analytical approach to the evidence 1 1.3 Structure of the document 2 2 What are high streets? 4 2.1 Towards a definition of high streets 4 3 Valuing the high street/town centre 8 3.1 Introduction 8 3.2 Planning priority 8 3.3 Economic and social value 9 4 High street changes and recent trends 13 4.1 Introduction 13 4.2 Changing representation of non-retail uses 14 4.3 Key retail performance indicators 16 4.4 The retailer perspective 31 4.5 Investor perspectives 32 4.6 How has the private sector responded? 32 4.7 Summary: the current position 33 5 The drivers of change 36 5.1 Introduction 36 5.2 Externalities 37 5.3 Physical and spatial factors 43 5.4 Market and competition factors 44 5.5 Demographic factors 57 5.6 Regulation and legislation 58 5.7 Centre management factors 59 5.8 Reflections on the drivers of high street change 60 6 What has been the response to high street change? 64 6.1 Introduction 64 6.2 Improving the built form and configuration 64 6.3 The drive for differentiation 67 6.4 Policy prioritisation 72 6.5 More developed -

The Virgin Group in 2012*

The Virgin Group in 2012* At the beginning of 2012, Richard Branson was 61 years old and his Virgin group of companies had been in business for 43 years. Yet neither Branson nor his business activities showed much sign of fl agging entrepreneurial vigor. In fi nancial services, Virgin Money was in the process of a major expansion of its UK retail presence through acquiring bank branches being sold off by Northern Rock and Lloyds Group. In health clubs, Virgin Active—boosted by its acquisition of rival Esporta—was expanding into new markets in Asia and Latin America. In healthcare, Virgin was using its acquisition of Assura to establish itself in primary healthcare services in the UK. In communication and computing services, Virgin’s initiatives included wireless services in Latin America and cloud computing services for corporate customers in the UK. In the travel business, Virgin continued to be a pioneer: Virgin Galactic spaceship service was undergoing test fl ights and selling seats at $200,000 each. Yet despite Branson’s prominence as Britain’s best-known entrepreneur and one of its richest individuals1—his Virgin group of companies remained a mystery to most observers (and to many insiders as well). At the beginning of 2012, there were 228 Virgin companies registered at Britain’s Companies House (68 of which were identifi ed as “removed” or “recently dissolved”). In addition, there were Virgin companies registered in some 25 other countries. These companies were linked through a complex network of parent-subsidiary relations involving a number of companies identifi ed as “holding companies”.