The Virgin Group in 2012*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

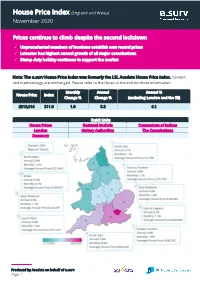

November 2020 Prices Continue to Climb

(England and Wales) House Price Index November 2020 Prices continue to climb despite the second lockdown ✓ Unprecedented numbers of locations establish new record prices ✓ Leicester has highest annual growth of all major conurbations ✓ Stamp duty holiday continues to support the market Note: The e.surv House Price Index was formerly the LSL Acadata House Price Index. Content and methodology are unchanged. Please refer to the Notes at the end for more information. Monthly Annual Annual % House Price Index Change % Change % (excluding London and the SE) £319,816 311.0 1.0 5.8 6.1 Quick Links House Prices Regional Analysis Comparison of Indices London Unitary Authorities The Conurbations Summary Produced by Acadata on behalf of e.surv Page 1 House Price Index (England and Wales) November 2020 Table 1. Average House Prices in England and Wales for the period November 2019 – November 2020 Link to source Excel Month Year House Price Index Monthly Change % Annual Change % November 2019 £302,368 294.3 0.4 1.5 December 2019 £302,886 294.6 0.2 1.5 January 2020 £304,088 295.7 0.4 1.7 February 2020 £306,012 297.6 0.6 1.9 March 2020 £305,457 297.1 -0.2 2.0 April 2020 £301,658 293.4 -1.2 1.0 May 2020 £298,672 290.5 -1.0 0.0 June 2020 £298,727 290.5 0.0 0.1 July 2020 £302,912 294.6 1.4 1.7 August 2020 £307,802 299.3 1.6 3.4 September 2020 £312,475 303.9 1.5 4.4 October 2020 £316,543 307.8 1.3 5.1 November 2020 £319,816 311.0 1.0 5.8 Note: The e.surv House Price Index provides the “average of all prices paid for domestic properties”, including those made with cash. -

Data Standards Manual Summary of Changes

October 2019 Visa Public gfgfghfghdfghdfghdfghfghffgfghfghdfghfg This document is a supplement of the Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules. In the event of any conflict between any content in this document, any document referenced herein, any exhibit to this document, or any communications concerning this document, and any content in the Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules, the Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules shall govern and control. Merchant Data Standards Manual Summary of Changes Visa Merchant Data Standards Manual – Summary of Changes for this Edition This is a global document and should be used by members in all Visa Regions. In this edition, details have been added to the descriptions of the following MCCs in order to facilitate easier merchant designation and classification: • MCC 5541 Service Stations with or without Ancillary Services has been updated to include all engine fuel types, not just automotive • MCC 5542 Automated Fuel Dispensers has been updated to include all engine fuel types, not just automotive • MCC 5812 Eating Places, Restaurants & 5814 Fast Food Restaurants have been updated to include greater detail in order to facilitate easier segmentation • MCC 5967 Direct Marketing – Inbound Telemarketing Merchants has been updated to include adult content • MCC 6540 Non-Financial Institutions – Stored Value Card Purchase/Load has been updated to clarify that it does not apply to Staged Digital Wallet Operators (SDWO) • MCC 8398 Charitable Social Service Organizations has -

Barings Bank Disaster Man Family of Merchants and Bankers

VOICES ON... Korn Ferry Briefings The Voice of Leadership HISTORY Baring, a British-born member of the famed Ger- January 17, 1995, the devastating earthquake in Barings Bank Disaster man family of merchants and bankers. Barings Kobe sent the Nikkei tumbling, and Leeson’s losses was England’s oldest merchant bank; it financed reached £827 million, more than the entire capital the Napoleonic Wars and the Louisiana Purchase, and reserve funds of the bank. A young rogue trader brings down a 232-year-old bank. and helped finance the United States government Leeson and his wife fled Singapore, trying to “I’m sorry,” he says. during the War of 1812. At its peak, it was a global get back to London, and made it as far as Frankfurt financial institution with a powerful influence on airport, where he was arrested. He fought extradi- the world’s economy. tion back to Singapore for nine months but was BY GLENN RIFKIN Leeson, who grew up in the middle-class eventually returned, tried, and found guilty. He was London suburb of Watford, began his career in sentenced to six years in prison and served more the mid-1980s as a clerk with Coutts, the royal than four years. His wife divorced him, and he was bank, followed by a succession of jobs at other diagnosed with colon cancer while in prison, which banks, before landing at Barings. Ambitious and got him released early. He survived treatment and aggressive, he was quickly promoted settled in Galway, Ireland. In the past to the trading floor, and in 1992 he was “WE WERE 24 years, Leeson remarried and had two appointed manager of a new operation sons. -

2018 Unaudited Interim Results for the Six Months Ended 30 September 2017

2018 UNAUDITED INTERIM RESULTS FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED 30 SEPTEMBER 2017 Brait SE (Registered in Malta as a European Company) (Registration No. SE1) Share code: BAT ISIN: LU0011857645 Bond code: WKN: A1Z6XC ISIN: XS1292954812 LEI code: 549300VB8GBX4UO7WG59 (“Brait”, the “Company” or “Group”) Item Page reference Section 1: Brait’s interim results presentation: Six months ended 30 September 2017 Contents3 ● Agenda 4 ● Brait six months ended 30 September 2017: - Performance against targets 5 - Brait NAV analysis 6 - Brait’s unaudited interim results 12 ● Portfolio performance review: - Virgin Active FY2017: Nine months ended 30 September 2017 14 - Iceland Foods FY2018: 24 weeks ended 8 September 2017 24 - Premier FY2018: Six months ended 30 September 2017 39 - New Look FY2018: 26 weeks ended 23 September 2017 53 - Other investments Update on portfolio 63 ● Conclusion 64 Section 2: Appendices 65 ● Brait overview 66 ● Brait’s Convertible Bond – overview and salient terms 69 ● Brait’s investment portfolio: Additional information including 5 year summarised financials - Virgin Active 70 - Iceland Foods 85 - Premier 96 - New Look 102 - Other investments 110 Notice to recipients 112 Section 3: Brait’s unaudited interim results announcement: Six months ended 30 September 2017 113 Unaudited results for the six months ended 30 September 2017 BRAIT’S INTERIM RESULTS PRESENTATION for the six months ended 30 September 2017 Interim Results: 30 September 2017 Agenda Welcome Brait Results: Six months ended 30 September 2017 Portfolio Virgin Active Results: -

Société Générale and Barings

Volume 17, Number 7 Printed ISSN: 1078-4950 PDF ISSN: 1532-5822 JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY FOR CASE STUDIES Editors Inge Nickerson, Barry University Charles Rarick, Purdue University, Calumet The Journal of the International Academy for Case Studies is owned and published by the DreamCatchers Group, LLC. Editorial content is under the control of the Allied Academies, Inc., a non-profit association of scholars, whose purpose is to support and encourage research and the sharing and exchange of ideas and insights throughout the world. Page ii Authors execute a publication permission agreement and assume all liabilities. Neither the DreamCatchers Group nor Allied Academies is responsible for the content of the individual manuscripts. Any omissions or errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. The Editorial Board is responsible for the selection of manuscripts for publication from among those submitted for consideration. The Publishers accept final manuscripts in digital form and make adjustments solely for the purposes of pagination and organization. The Journal of the International Academy for Case Studies is owned and published by the DreamCatchers Group, LLC, PO Box 1708, Arden, NC 28704, USA. Those interested in communicating with the Journal, should contact the Executive Director of the Allied Academies at [email protected]. Copyright 2011 by the DreamCatchers Group, LLC, Arden NC, USA Journal of the International Academy for Case Studies, Volume 17, Number 7, 2011 Page iii EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Irfan Ahmed Devi Akella Sam Houston State University Albany State University Huntsville, Texas Albany, Georgia Charlotte Allen Thomas T. Amlie Stephen F. Austin State University SUNY Institute of Technology Nacogdoches, Texas Utica, New York Ismet Anitsal Kavous Ardalan Tennessee Tech University Marist College Cookeville, Tennessee Poughkeepsie, New York Joe Ballenger Lisa Berardino Stephen F. -

THE COLLAPSE of BARINGS BANK and LEHMAN BROTHERS HOLDINGS INC: an ABRIDGED VERSION Juabin Matey, Bcom, UCC, Ghana. Mgoodluck369

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 8 October 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202007.0006.v3 THE COLLAPSE OF BARINGS BANK AND LEHMAN BROTHERS HOLDINGS INC: AN ABRIDGED VERSION Juabin Matey, Bcom, UCC, Ghana. [email protected] James Dianuton Bawa, MSc (Student) Industrial Finance and Investment, KNUST, Ghana. [email protected] ABSTRACT Bank crisis is mostly traced to a decrease in the value of bank assets. This occurs in one or a combination of the following incidences; when loans turn bad and cease to perform (credit risk), when there are excess withdrawals over available funds (liquidity risk) and rising interest rates (interest rate risk). Bad credit management, market inefficiencies and operational risk are among a host others that trigger panic withdrawals when customers suspect a loss of investment. This brief article makes a contribution on why Barings Bank and Lehman Brothers failed and lessons thereafter. The failure of Barings Bank and Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc was as a result of an array of factors spanning from lack of oversight role in relation to employee conduct the course performing assigned duties to management’s involvement in dubious accounting practices, unethical business practices, over indulging in risky and unsecured derivative trade. To guide against similar unfortunate bank collapse in the near future, there should be an enhanced communication among international regulators and authorities that exercise oversight responsibilities on the security market. National bankruptcy laws should be invoked to forestall liquidity crisis so as to prevent freezing of margins and positions of solvent customers. © 2020 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. -

Hot and Cold Seasons in the Housing Market∗

Hot and Cold Seasons in the Housing Market L. Rachel Ngai Silvana Tenreyro London School of Economics, CEP, and CEPR April 2013 Abstract Every year housing markets in the United Kingdom and the United States experience system- atic above-trend increases in both prices and transactions during the second and third quarters (the “hot season”) and below-trend falls during the fourth and first quarters (the “cold sea- son”). House price seasonality poses a challenge to existing models of the housing market. To explain seasonal patterns, this paper proposes a matching model that emphasizes the role of match-specific quality between the buyer and the house and the presence of thick-market effects in housing markets. It shows that a small, deterministic driver of seasonality can be amplified and revealed as deterministic seasonality in transactions and prices, quantitatively mimicking the seasonal fluctuations observed in the United Kingdom and the United States. Key words: housing market, thick-market effects, search-and-matching, seasonality, house price fluctuations, match quality For helpful comments, we would like to thank James Albrecht, Robert Barro, Francesco Caselli, Tom Cunningham, Morris Davis, Steve Davis, Jordi Galí, Christian Julliard, Peter Katuscak, Philipp Kircher, Nobu Kiyotaki, John Leahy, Francois Ortalo-Magné, Denise Osborn, Chris Pissarides, Richard Rogerson, Kevin Sheedy, Jaume Ventura, Randy Wright, and seminar participants at the NBER Summer Institute, SED, and various universities and central banks. For superb research assistance, we thank Jochen Mankart, Ines Moreno-de-Barreda, and Daniel Vernazza. Tenreyro acknowledges financial support from the European Research Council under the European Community’s ERC starting grant agreement 240852 Research on Economic Fluctuations and Globalization, Bank of Spain through CREI’sAssociate Professorship, and STICERD starting grant. -

Virgin Mobile Holdings (Uk)

A copy of this document, comprising listing particulars relating to Virgin Mobile Holdings (UK) plc (the Company) prepared solely in connection with the proposed offer to certain institutional and professional investors (the Global Offer) of ordinary shares (the Ordinary Shares) in the Company in accordance with the Listing Rules made under section 74 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA), has been delivered for registration to the Registrar of Companies in England and Wales pursuant to section 83 of FSMA. Application has been made to the UK Listing Authority for the ordinary share capital of Virgin Mobile Holdings (UK) plc to be admitted to the Official List of the UK Listing Authority and to the London Stock Exchange for such share capital to be admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s market for listed securities. It is expected that admission to listing and trading will become effective and that unconditional dealings will commence at 8.00 a.m. on 26 July 2004. All dealings in Ordinary Shares prior to the commencement of unconditional dealings will be on a ‘‘when issued’’ basis and of no effect if Admission does not take place and will be at the sole risk of the parties concerned. The Directors of Virgin Mobile Holdings (UK) plc, whose names appear on page 8 of this document, accept responsibility for the information contained in this document. To the best of the knowledge and belief of the Directors (who have taken all reasonable care to ensure that such is the case), the information contained in this document is in accordance with the facts and does not omit anything likely to affect the import of such information. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Case Fifteen

AGFC15 16/12/2004 17:16 Page 120 case fifteen Richard Branson and the Virgin Group of Companies in 2004 TEACHING NOTE SYNOPSIS By 2004, Richard Branson’s business empire extended from airlines and railways to financial services and mobile telephone services. There was little evidence of any slow- ing up of the pace of new business startups. In the first 4 years of the new century, Virgin had founded a new airline in Australia; retail ventures in Singapore and Thailand; wireless telecom companies in Asia, the US, and Australia; and a wide variety of online retailing. While several of these new ventures had been very successful (the Australian airline Virgin Blue and Virgin Mobile in particular), the financial health of several other Virgin companies was looking precarious. Several of Branson’s startups had been financial disasters – Virgin Cola and Victory Corporation in par- ticular. Other more established members of the Virgin group (such as Virgin Rail and Virgin Atlantic) required substantial investment, while yielding disappointing operating earnings. While Branson’s enthusiasm for supporting new business ideas and launching companies that would challenge business orthodoxy and seek new approaches to meeting customer needs seemed to be undiminished, skeptics sug- gested that the Virgin brand had become overextended and that Branson was losing his golden touch. The case outlines the development of the Virgin group of companies from Branson’s first business venture and offers insight into the nature of Branson’s leadership, the This note was prepared by Robert M. Grant. 120 AGFC15 16/12/2004 17:16 Page 121 RICHARD BRANSON AND THE VIRGIN GROUP OF COMPANIES IN 2004 121 management principles upon which the Virgin companies are launched and operated, and the way in which the group is run. -

VIRGIN GROUP Resource: Exploring Corporate Strategy Introduction the Virgin Group Is One of the UK's Largest Private Companies

VIRGIN GROUP Resource: Exploring Corporate Strategy Introduction The Virgin Group is one of the UK's largest private companies, with an annual turnover estimated at £3bn per annum by 2000. Virgin's highest-profile business was Virgin Atlantic, which had developed to be a major force in the international airline business. However, the group spanned over 200 businesses from financial services through to railways; from entertainment mega stores and soft drinks to cosmetics and condoms. (Figure 1 shows the breadth of the group's activities.) Its name was instantly recognizable. Research showed that the Virgin name was associated with words such as 'fun', 'innovative', 'daring' and 'successful'. The personal image and personality of the founder, Richard Branson, were high profile; in British advertisements for Apple Computers, together with Einstein and Gandhi, he was featured as a 'shaper of the 20th century'. Origins and ownership Virgin was founded in 1970 as a mail order record business and developed as a private company in music publishing and retailing. In 1986 the company was floated on the stock exchange with a turnover of £250 million. However, Branson became tired of the public listing obligations. Compliance with the rules governing public limited companies and reporting to shareholders were expensive and time-consuming, and he resented making presentations in the City to people whom, he believed, did not understand the business. The pressure to create short-term profit, especially as the share price began to fall, was the final straw: Branson decided to take the business back into private ownership and the shares were bought back at the original offer price, which valued the company at £240 million. -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal For

ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 2016 For personal use only ACN: 100 686 226 Annual financial report For the year ended 30 June 2016 Contents Annual financial report Directors’ report 1 Lead auditor’s independence declaration 38 Consolidated financial statements 39 Directors’ declaration 97 Independent auditor’s report 98 ASX additional information 100 Corporate directory 103 For personal use only This financial report covers the Virgin Australia Holdings Limited Group, consisting of Virgin Australia Holdings Limited and its controlled entities. The financial report is presented in Australian dollars. Virgin Australia Holdings Limited (VAH) is a company limited by shares, incorporated and domiciled in Australia. Details of its registered office and principal place of business are on page 103. Through the use of the internet, we have ensured that our corporate reporting is timely, complete and available globally at minimum cost to the Company. All press releases, financial reports and other information are available at our Shareholder Information Centre on our website: www.virginaustralia.com. Directors’ report The directors present their report together with the consolidated financial statements of the Group comprising Virgin Australia Holdings Limited (VAH) (the Company) and its subsidiaries, and the Group’s interests in associates and joint ventures, for the financial year ended 30 June 2016 and the auditor’s report thereon. Directors The directors of the Company at any time during or since the end of the financial year are: Ms Elizabeth Bryan