Accounting for Uk Retailers' Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2020 Prices Continue to Climb

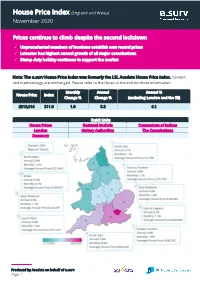

(England and Wales) House Price Index November 2020 Prices continue to climb despite the second lockdown ✓ Unprecedented numbers of locations establish new record prices ✓ Leicester has highest annual growth of all major conurbations ✓ Stamp duty holiday continues to support the market Note: The e.surv House Price Index was formerly the LSL Acadata House Price Index. Content and methodology are unchanged. Please refer to the Notes at the end for more information. Monthly Annual Annual % House Price Index Change % Change % (excluding London and the SE) £319,816 311.0 1.0 5.8 6.1 Quick Links House Prices Regional Analysis Comparison of Indices London Unitary Authorities The Conurbations Summary Produced by Acadata on behalf of e.surv Page 1 House Price Index (England and Wales) November 2020 Table 1. Average House Prices in England and Wales for the period November 2019 – November 2020 Link to source Excel Month Year House Price Index Monthly Change % Annual Change % November 2019 £302,368 294.3 0.4 1.5 December 2019 £302,886 294.6 0.2 1.5 January 2020 £304,088 295.7 0.4 1.7 February 2020 £306,012 297.6 0.6 1.9 March 2020 £305,457 297.1 -0.2 2.0 April 2020 £301,658 293.4 -1.2 1.0 May 2020 £298,672 290.5 -1.0 0.0 June 2020 £298,727 290.5 0.0 0.1 July 2020 £302,912 294.6 1.4 1.7 August 2020 £307,802 299.3 1.6 3.4 September 2020 £312,475 303.9 1.5 4.4 October 2020 £316,543 307.8 1.3 5.1 November 2020 £319,816 311.0 1.0 5.8 Note: The e.surv House Price Index provides the “average of all prices paid for domestic properties”, including those made with cash. -

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Haddock-Millar, Julie and Rigby, Chris (2015) Business strategy and the environment Tesco Plc’s declining financial performance and underlying issues. Review of Business and Finance Studies, 6 (3) . pp. 91-103. ISSN 2150-3338 [Article] Published version (with publisher’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/18143/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Hertfordshire

CORPORATIONS AND BUSINESSES • This list includes current companies that are involved in supporting local arts charities and those who have headquarters in the region. • For large national companies with a policy a link is provided to their site and a summary of what they support. Some companies do not have a stated policy but there contact details are provided. • For smaller local companies, they are listed as supporters on arts organisations websites, the nature of the support is not always clear œ it may be financial or in kind, or favoured suppliers who offer charity discounts. General contacts B & Q support for communities http://www.diy.com/diy/jsp/corporate/content/environment_ethics/ethics/comm unity/waste_donation.jsp Opportunities to get supplies, paint etc., from local B&Q stores. 02 Think Big http://www.o2thinkbig.co.uk/ ®¥¥∞∑∑∑Ø ¥®©Æ´¢©ß£Øµ´ Grants of £300 - £2500 for projects that make positive changes to people‘s communities. Eligible: Young people aged 14-25 W hitbread Houghton Hall Business Park Porz Ave Dunstable LU5 5XE 01582 424200 [email protected] http://www.whitbread.co.uk/whitbread/responsibility/team-community/community- investment-whr.html They are interested in local partnerships with charities. Three schemes they run by different brands owned by Whitbread are: 1. Table Kits for Clubsœ for sports, dance, singing (any group) purchasing of uniforms 01582 844 360 2. Beefeater Community Champions œ grants of up to £1000 for community champions 01582 844 360 3. Brewers Fayre Local Heroes 01582 844 360 (ERTFORDSHIRE Astrium Astrium Ltd Gunnels Wood Road Stevenage Hertfordshire, SG1 2AS http://www.astrium.eads.net/ No stated policy. -

The Co-Creation of a Retail Innovation: Shoppers and the Early Supermarket in Britain. Andrew Alexander , Dawn Nell , Adrian R

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE The co-creation of a retail Innovation: shoppers and the early supermarket in Britain AUTHORS Alexander, Andrew; Nell, Dawn; Bailey, Adrian R.; et al. JOURNAL Enterprise and Society DEPOSITED IN ORE 28 January 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4221 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication The Co-Creation of a Retail Innovation: Shoppers and the Early Supermarket in Britain. Andrew Alexander a, Dawn Nell b, Adrian R. Bailey c, Gareth Shaw c a School of Management, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey, GU2 7XH UK Email: A.Alexander @surrey.ac.uk bSchool of Management, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey, GU2 7XH UK cBusiness School, University of Exeter, Exeter EX4 4PU, UK This is an author copy of a paper published in Enterprise & Society Vol. 10 (3), 529-558 (2009). As such its format may differ from the final version published in the journal. Figure 1 is provided at the end of the paper. INTRODUCTION The supermarket is an important innovation that transformed retailing in post-war Britain.1 However, detailed explorations of shoppers’ reactions toward, and involvement in, the changing service encounters occurring in these new retail formats are generally lacking. This is a significant shortcoming because shoppers had to negotiate fundamental changes to their interactions with the physical environment of the store, the retail staff, other customers, and the products for sale.2 In this paper we begin to fill this gap in understanding through an analysis of the attitudes and behaviours of those who shopped at the early supermarkets (up to about 1975). -

Prospectus Dated 5 July 2016

This document comprises a prospectus (the ‘‘Prospectus’’) for the purposes of Article 3 of EU Directive 2003/71/EC, as amended (the ‘‘Prospectus Directive’’) relating to the New Sainsbury’s Shares and has been prepared in accordance with the Prospectus Rules of the Financial Conduct Authority (the ‘‘FCA’’) made under section 73A of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (the ‘‘FSMA’’). The Prospectus will be made available to the public in accordance with the Prospectus Rules. The directors of J Sainsbury plc (‘‘Sainsbury’s’’ or the ‘‘Company’’), whose names appear on page 44 of this Prospectus, and the Company accept responsibility for the information contained in this Prospectus. To the best of the knowledge of the Company and the Sainsbury’s Directors (each of whom has taken all reasonable care to ensure that such is the case), the information contained in this Prospectus is in accordance with the facts and contains no omission likely to affect the import of such information. Investors are advised to examine all the risks that might be relevant in connection with the value of an investment in the New Sainsbury’s Shares. Investors should read the entire Prospectus (including the documents, or parts thereof, incorporated by reference) and, in particular, the section headed ‘‘Risk Factors’’ for a discussion of certain factors that should be considered in connection with an investment in the Company, the Combined Group, the existing Sainsbury’s Shares and the New Sainsbury’s Shares. J SAINSBURY PLC (incorporated under the Companies -

Hot and Cold Seasons in the Housing Market∗

Hot and Cold Seasons in the Housing Market L. Rachel Ngai Silvana Tenreyro London School of Economics, CEP, and CEPR April 2013 Abstract Every year housing markets in the United Kingdom and the United States experience system- atic above-trend increases in both prices and transactions during the second and third quarters (the “hot season”) and below-trend falls during the fourth and first quarters (the “cold sea- son”). House price seasonality poses a challenge to existing models of the housing market. To explain seasonal patterns, this paper proposes a matching model that emphasizes the role of match-specific quality between the buyer and the house and the presence of thick-market effects in housing markets. It shows that a small, deterministic driver of seasonality can be amplified and revealed as deterministic seasonality in transactions and prices, quantitatively mimicking the seasonal fluctuations observed in the United Kingdom and the United States. Key words: housing market, thick-market effects, search-and-matching, seasonality, house price fluctuations, match quality For helpful comments, we would like to thank James Albrecht, Robert Barro, Francesco Caselli, Tom Cunningham, Morris Davis, Steve Davis, Jordi Galí, Christian Julliard, Peter Katuscak, Philipp Kircher, Nobu Kiyotaki, John Leahy, Francois Ortalo-Magné, Denise Osborn, Chris Pissarides, Richard Rogerson, Kevin Sheedy, Jaume Ventura, Randy Wright, and seminar participants at the NBER Summer Institute, SED, and various universities and central banks. For superb research assistance, we thank Jochen Mankart, Ines Moreno-de-Barreda, and Daniel Vernazza. Tenreyro acknowledges financial support from the European Research Council under the European Community’s ERC starting grant agreement 240852 Research on Economic Fluctuations and Globalization, Bank of Spain through CREI’sAssociate Professorship, and STICERD starting grant. -

Hull Core Strategy - Contacts List (As at July 2011)

Hull Core Strategy - Contacts List (as at July 2011) Introduction This report provides details about the contacts made during the development of the Hull Core Strategy. It includes contact made at each plan making stage, as follows: • Issues and Options – August 2008 • Emerging Preferred Approach – February 2010 • Core Strategy Questionnaire – September 2010 • Spatial Options – February 2011 • Core Strategy Publication Version – July 2011 A list of Hull Development Forum members (as at July 2011) is also enclosed. This group has met over 15 times, usually on a quarterly basis. The report also sets out the specific and general organisations and bodies that have been contacted, in conformity with the Council’s adopted Statement of Community Involvement. Specific groups are indicated with an asterisk. Please note contacts will change over time. Issues and Options – August 2008 (Letter sent to Consultants/Agents) Your Ref: My Ref: PPI/KG/JP Contact: Mr Keith Griffiths «Title» «First_Name» «Surname» Tel: 01482 612389 «Job_Title» Fax: 01482 612382 Email: [email protected] «Org» th «Add1» Date: 4 August 2008 «Add2» «Add3» «Town» «Postcode» Dear Sir/Madam Hull Core Strategy - issues, options and suggested preferred option Please find enclosed the ‘Hull Core Strategy issues, options and suggested preferred option’ document for your consideration. Your views should be returned to us by the 5 September, 2008 by using the form provided. In particular, could you respond to the following key questions: 1. What do you think to the issues, objectives, options and suggested preferred option set out in the document? 2. How would you combine the options? 3. -

The Global Grocery and General Merchandising Market Marketing Essay

The Global Grocery And General Merchandising Market Marketing Essay Jack Cohen founded Tesco in 1919 when he began to sell surplus groceries from a stall at Well Street Market, Hackney, in the East End of London (ironically, the market is now much smaller than in those days; a large Tesco Metro store now sits on the site.)[11] The Tesco brand first appeared in 1924. The name came about after Jack Cohen bought a shipment of tea from T.E. Stockwell. He made new labels using the first three letters of the supplier’s name (TES), and the first two letters of his surname (CO), forming the word TESCO.[12] The first Tesco store was opened in 1929 in Burnt Oak, Edgware, Middlesex. Tesco was floated on the London Stock Exchange in 1947 as Tesco Stores (Holdings) Limited.[11] The first self-service store opened in St Albans in 1956 (which remained operational until 2010, with a period as a Tesco Metro),[13] and the first supermarket in Maldon in 1956.[11] During the 1950s and the 1960s Tesco grew organically, and also through acquisitions, until it owned more than 800 stores. The company purchased 70 Williamsons stores (1957), 200 Harrow Stores outlets (1959), 212 Irwins stores (1960, beating Express Dairies Premier Supermarkets to the deal), 97 Charles Phillips stores (1964) and the Victor Value chain (1968) (sold to Bejam in 1986).[14] Originally specialising in food and drink, it has diversified into areas such as clothing, electronics, financial services, telecoms, home, health, car, dental and pet insurance, retailing and renting DVDs,[10] CDs, music downloads, Internet services and software. -

Retail Change: a Consideration of the UK Food Retail Industry, 1950-2010. Phd Thesis, Middlesex University

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Clough, Roger (2002) Retail change: a consideration of the UK food retail industry, 1950-2010. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/8105/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Start 2003 PP16

start AUGUST 2003 start WRITE AWAY When you write to Group Reward and Benefits This magazine is intended to be informative Department, please remember to tell us: rather than technical and detailed. It provides ● Your full name, company and current a broad outline of the Group Benefits home address arrangements, including ShareSave, All- ● Your National Insurance number Employee Share Options, the Kingfisher Pension ● Your employee number Scheme and the Kingfisher Retirement Trust. ● And if you’re a member of the Retirement Although still only summaries, a more detailed Trust, we’ll need your member number as well. explanation is contained in the various You should contact your personnel or payroll department if explanatory guides issued to members. The you receive any documents (like your Benefit Statement) from us that show the legal position is governed by the formal Trust wrong personal details. They will let us know, so you don’t have to bother. Deeds and Rules, copies of which are available to members. Legal reliance should only be However, if we haven’t got your right date of birth or if your name has changed on placed on these formal documents. marriage, you will need to contact us and send a copy of the Birth or Marriage Certificate - we always send original forms back via Registered Post. Please remember that we can’t make any changes unless we are notified in writing. Our new address for enquiries is Group Reward and Benefits Department, CONTENTS Kingfisher plc, 3 Sheldon Square, Paddington, London W2 6PX. 4 Discount Scheme 6 Share Schemes FURTHER INFORMATION 8 Scheme and Trust For further information about Pensions, ShareSave or the Discount Scheme, you can contact the person listed for your company. -

The Consumer-Creditors of Bankrupt, Abandoned, Defunct and of Zombie Companies’ (2019) 24(1) Tilburg Law Review Pp

TILBURG LAW REVIEW Tibor Tajti(Thaythy), ‘Unprotected Consumers in the Digital Journal of International and European Law Age: The Consumer-creditors of Bankrupt, Abandoned, Defunct and of Zombie Companies’ (2019) 24(1) Tilburg Law Review pp. 3–26, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/tilr.139 RESEARCH ARTICLE Unprotected Consumers in the Digital Age: The Consumer-creditors of Bankrupt, Abandoned, Defunct and of Zombie Companies Tibor Tajti(Thaythy)* The aim of this article1 is to draw the attention of comparative scholars, researchers and policy-makers to the inferior position of consumer-creditors in bankruptcy proceedings, a topic that escaped attention during the development of financial protection of consumers in Europe. Consumers may become creditors if they prepay certain goods or services that remain undelivered following bankruptcy of a retailer or service-provider. The problem that results is that consumer-creditors are treated as unsecured creditors in bankruptcy law, who rank very low on the priority ladder and are doomed to recover only a small fraction of their claims, if anything at all. In order to fill the vacuum, the article attempts to map the real dimensions of the consumer-creditor problem first by outlining the spectrum of bankruptcy cases involving consumer-creditors and the threats to consumers inherent to abandoned and defunct companies that are usually left without assets creditors could collect upon. This includes case studies of major recent bankruptcies caused by appearance of new technologies (e.g., the collapse of -

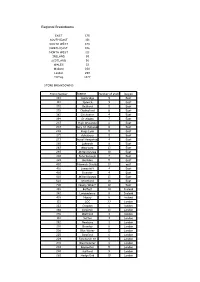

Regional Breakdowns Name

Regional Breakdowns EAST 175 SOUTH EAST 131 SOUTH WEST 174 NORTH EAST 106 NORTH WEST 113 IRELAND 30 SCOTLAND 96 WALES 32 Midland 230 London 290 TOTAL 1377 STORE BREAKDOWNS Store Number Name Number of staff Region 123 Cambridge 9 East 141 Ipswich 9 East 172 Bedford 5 East 175 Chelmsford 8 East 182 Colchester 4 East 194 St Albans 7 East 237 High Wycombe 6 East 247 Bury St. Edmunds 8 East 248 Kings Lynn 5 East 271 Aylesbury 5 East 273 Hemel Hempstead 4 East 285 Lakeside 8 East 287 Moorgate 13 East 297 Milton Keynes 10 East 302 Peterborough 7 East 322 Basildon 5 East 402 Norwich Cfields 13 east 416 Lowestoft 4 East 460 Bicester 4 East 510 Milton Keynes 13 East 522 Stratford 18 East 700 Canary Wharf 10 East 188 Belfast 14 Ireland 342 Londonderry 8 Ireland 418 Newry 8 ireland 121 LOC 33 London 132 Croydon 6 london 148 Kingston 13 London 178 Watford 4 london 181 Sutton 3 London 192 Newbury 3 London 201 Bromley 8 London 206 Blue Water 12 London 225 Romford 6 London 229 Fenchurch St 5 London 231 Westminster 6 London 232 Bayswater 5 London 240 Guilford 9 London 282 Hedge End 10 London 289 Putney 6 London 290 Greenford 5 London 292 Kensington 9 London 293 Strand 15 London 308 Staines 3 London 329 Uxbridge 4 London 330 Richmond 7 London 359 Camberley 4 London 366 Islington 8 London 377 Woking 5 London 378 Redhill 5 London 398 Harrow 5 London 405 Clapham 5 London 431 Crawley 4 London 432 Holborn 6 London 438 Wimbledon 6 London 464 Enfield 5 London 470 Wood Green 5 London 472 Epsom 6 London 479 White City 13 london 511 Oxford St 25 London 518 Hounslow