Inherited Thrombophilic Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

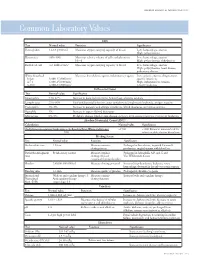

Common Laboratory Values

AmericAn AcAdemy of PediAtric dentistry Reference Manual 2006-2007 Resource Section 251 Common LaboratoryCommon Values Laboratory Values CBC Test Normal value Function Significance Hemoglobin 12-18 g/100 mL Measures oxygen carrying capacity of blood Low: hemorrhage, anemia High: polycythemia Hematocrit 35%-50% Measures relative volume of cells and plasma in Low: hemorrhage, anemia blood High: polycythemia, dehydration Red blood cell 4-6 million/mm3 Measures oxygen-carrying capacity of blood Low: hemorrhage, anemia High: polycythemia, heart disease, pulmonary disease White blood cell Measures host defense against inflammatory agents Low: aplastic anemia, drug toxicity, Infant 8,000-15,000/mm3 specific infections 4-7 y 6,000-15,000/mm3 High: inflammation, trauma, 8-18 y 4,500-13,500/mm3 toxicity, leukemia Differential Count Test Normal value Significance Neutrophils 54%-62% Increase in bacterial infections, hemorrhage, diabetic acidosis Lymphocytes 25%-30% Viral and bacterial infection, acute and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, antigen reaction Eosinophils 1%-3% Increase in parasitic and allergic conditions, blood dyscrasias, pernicious anemia Basophils 1% Increase in types of blood dyscrasias Monocytes 0%-9% Hodgkin’s disease, lipid storage disease, recovery from severe infections, monocytic leukemia Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC) Calculation Normal value Significance (% Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes + % Bands)×Total White Cell Count >1500 <1000 Patient at increased risk for 100 infection; defer elective dental care Bleeding Screen Test -

Prothrombin Time (PT) Be Kept in Constant and Incubation Temperature at Step 3, Start Stop Watch , Mix in a Water Bath ( 37°C ) (LIQUID REAGENT) 36.5-37.5°C

components of any other kit with different lot numbers. temperature 15 minutes prior to testing. Throughout testing all test tubes, syringes and pipettes 2. Pre-warm PT reagent at 37°C for 5 minutes. should be plastic. 3. Pipette 100µl of PT reagent to each tube. Throughout testing all test tubes, incubation time should 4. Add 50 µl of sample, controls to the tubes prepared in Prothrombin Time (PT) be kept in constant and incubation temperature at step 3, start stop watch , mix in a water bath ( 37°C ) (LIQUID REAGENT) 36.5-37.5°C. for 8 seconds , then record the time required for clot For In-Vitro diagnostic use only If testing is delayed for more than 4 hours, plasma may formation . be stored at 2-8°C. B.Automated Method Store at: 2-8°C Each laboratory should establish a Quality Control To perform this test, refer to the appropriate Instrument program that includes both normal and abnormal control Operator’s Manual for detailed instructions. INTENDED USE plasmas to evaluate instrument, reagent tested daily Prothrombin Time (PT) is commonly used for screening for prior to performing tests on patient plasmas. Monthly RESULTS extrinsic factor deficiency, monitoring oral anticoagulant quality control charts are recommended to determine Clot time of the test Prothrombin Time plasma therapy and quantitative determination of the extrinsic the mean and standard deviation of each of the daily = Ratio (PTR) Clot time of the control coagulation factors. control plasma. All assays should include controls, and if plasma any of the controls are outside the established reference INR = PTRISI PRINCIPLE ranges, then the assay should be considered invalid and Example: for a PTR of 2.0 and an ISI of 1.0 Tissue thromboplastin, in the presence of calcium ions and no patient results should be reported. -

Severity of Anaemia Has Corresponding Effects on Coagulation Parameters of Sickle Cell Disease Patients

diseases Article Severity of Anaemia Has Corresponding Effects on Coagulation Parameters of Sickle Cell Disease Patients Samuel Antwi-Baffour 1,* , Ransford Kyeremeh 1 and Lawrence Annison 2 1 Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, School of Allied Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana, P.O. Box KB 143 Accra, Ghana; [email protected] 2 Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, School of Allied Health Sciences, Narh-Bita College, P.O. Box Co1061 Tema, Ghana; [email protected] * Correspondence: s.antwi-baff[email protected] Received: 31 July 2019; Accepted: 18 October 2019; Published: 17 December 2019 Abstract: Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited condition characterized by chronic haemolytic anaemia. SCD is associated with moderate to severe anaemia, hypercoagulable state and inconsistent platelet count and function. However, studies have yielded conflicting results with regards to the effect of anaemia on coagulation in SCD. The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of anaemia severity on selected coagulation parameters of SCD patients. Four millilitres of venous blood samples were taken from the participants (SCD and non-SCD patients) and used for analysis of full blood count and coagulation parameters. Data was analysed using SPSS version-16. From the results, it was seen that individuals with SCD had a prolonged mean PT, APTT and high platelet count compared to the controls. There was also significant difference in the mean PT (p = 0.039), APTT (p = 0.041) and platelet count (p = 0.010) in HbSS participants with severe anaemia. Mean APTT also showed significant difference (p = 0.044) with severe anaemia in HbSC participants. -

Research Article D-Dimer and Prothrombin Time Are the Significant Indicators of Severe COVID-19 and Poor Prognosis

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2020, Article ID 6159720, 10 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6159720 Research Article D-Dimer and Prothrombin Time Are the Significant Indicators of Severe COVID-19 and Poor Prognosis Hui Long,1 Lan Nie,2 Xiaochen Xiang,2 Huan Li,1 Xiaoli Zhang,1 Xiaozhi Fu,1 Hongwei Ren,1 Wanxin Liu,2 Qiang Wang ,2 and Qingming Wu 1,2 1Internal Medicine of Tianyou Hospital, Wuhan University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430064, China 2Institute of Infection, Immunology and Tumor Microenvironment, Hubei Province Key Laboratory of Occupational Hazard Identification and Control, Medical College, Wuhan University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430065, China Correspondence should be addressed to Qiang Wang; [email protected] and Qingming Wu; [email protected] Received 22 April 2020; Accepted 19 May 2020; Published 17 June 2020 Academic Editor: Frederick D. Quinn Copyright © 2020 Hui Long et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Objective. To investigate the value of coagulation indicators D-dimer (DD), prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), thrombin time (TT), and fibrinogen (Fg) in predicting the severity and prognosis of COVID-19. Methods. A total of 115 patients with confirmed COVID-19, who were admitted to Tianyou Hospital of Wuhan University of Science and Technology between January 18, 2020, and March 5, 2020, were included. The dynamic changes of DD, PT, APTT, and Fg were tested, and the correlation with CT imaging, clinical classifications, and prognosis was studied. -

Thrombophilia Testing Panel Now Available

Thrombophilia Testing Panel Now Available Bronson Laboratory offers a any impact on the patient’s therapy. Importantly, most people with an thrombophilia testing panel consisting For instance, the vast majority of older inheritable thrombophilic mutation will of the following: factor VIII activity, anti- patients with venous thromboses in the never experience a thrombotic event, thrombin III activity, protein setting of a recognized inciting event and most of those who do will never C activity, protein S antigen, factor V Leiden will not have a preexisting thrombophilic do so again. Because of this, screening mutation assay, prothrombin 90210A condition, and accordingly testing is the general population or even asympto- mutation assay, and a lupus anticoagulant generally not recommended in this pop- matic relatives of individuals with thrombo- assay. Abnormal values for protein C, ulation. In regards to arterial thromboses, philic mutations is discouraged because protein S, and antithrombin III will be the overwhelming majority are a direct of the potential for harmful overtreatment. automatically reflexed to confirmatory consequence of atherosclerosis, and the By similar reasoning, some hematologists testing at the Mayo Clinic laboratories. added presence of a thrombophilia in would recommend the same period of Although these tests are orderable indi- this setting will not affect patient anticoagulation, often 3-6 months after vidually, there is little rationale to do so management. (continued on page 4) except as noted below. Clinical circumstances that suggest The activity assays are clotting tests a laboratory evaluation for thrombophilia that require adequate amounts of func- tional protein to achieve a normal result. For reasons having to do with greater achievable precision, the free protein S Patient with a Asymptomatic patients Other clinical situations with a family history of VTE antigen test is used in lieu of an activity confirmed acute VTE assay, but it too depends on adequate amounts of circulating protein for a normal finding. -

Association Between Coagulation Function and Patients with Primary Angle Closure Glaucoma: a 5-Year Retrospective Case–Control Study

Open Access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016719 on 4 November 2017. Downloaded from Association between coagulation function and patients with primary angle closure glaucoma: a 5-year retrospective case–control study Shengjie Li,1 Yanting Gao,1 Mingxi Shao,1 Binghua Tang,1 Wenjun Cao,1,2 Xinghuai Sun2,3,4,5 To cite: Li S, Gao Y, Shao M, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study et al. Association between Objective To evaluate the association between coagulation function and coagulation function and patients with primary angle patients with primary ► This is the first study focusing on the evaluation of closure glaucoma (PACG). angle closure glaucoma: a the coagulation function in primary angle closure 5-year retrospective case– Design A retrospective, hospital-based, case–control glaucoma (PACG) and its relationship with disease control study. BMJ Open study. severity. 2017;7:e016719. doi:10.1136/ Setting Shanghai, China. ► The large number of studied subjects. bmjopen-2017-016719 Participants A total of 1778 subjects were recruited from ► The detailed demographic and clinical data of the Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University from January ► Prepublication history and studied subjects. additional material for this paper 2010 to December 2015, including patients with PACG ► The nature of this study was a single eye centre, are available online. To view (male=296; female=569) and control subjects (male=290; retrospective case–control study. please visit the journal (http:// female=623). ► Statistical power analysis for specificity ability was dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ bmjopen- Outcome measures Sociodemographic data and limited. 2017- 016719). -

EDUCATION Four Compartments

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2014; 44:42–5 CME http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2014.110 © 2014 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Coagulation YL Chee Consultant Haematologist, Department of Haematology-Oncology, National University Hospital, Singapore ABSTRACT The haemostatic system comprises four compartments: the vasculature, Correspondence to YL Chee platelets, coagulation factors, and the fibrinolytic system. There is presently no Consultant Haematologist laboratory or near-patient test capable of reproducing the complex regulated Department of Haematology- Oncology interaction between these four compartments. The prothrombin time (PT) and NUHS Tower Block Level 7 activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) only test the coagulation protein 1E Kent Ridge Road compartment of the system and results have to be carefully interpreted in the Singapore 119228 context of the clinical presentation and assay limitations. This article will give a e-mail general overview of the limitations of PT and APTT and discuss specific issues that [email protected] need to be considered when the tests are requested, in the context of anticoagulant monitoring, bleeding symptoms, and routine preoperative screening. Of these indications, routine preoperative screening is the most controversial and is generally not warranted in the absence of an abnormal bleeding history. KEYWORDS Prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, thrombin clotting time, preoperative screening, bleeding history, coagulation screen DECLARATIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION Intrinsic pathway Extrinsic pathway The normal haemostatic system comprises four Factor XII/HMWK*/PK** compartments, the vasculature, platelets, coagulation proteins and the fibrinolytic system. When a blood Factor XI Factor XIa vessel is injured, all four compartments interact in a coordinated manner to prevent blood loss by forming a Factor IX Factor IXa Factor VIIa clot and localising this to the area of injury. -

Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT) CPT: 85730

Medicare National Coverage Determination Policy Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT) CPT: 85730 CMS National Coverage Policy Coverage Indications, Limitations, and/or Medical Necessity Basic plasma coagulation function is readily assessed with a few simple laboratory tests: The Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT), Prothrombin Time (PT), Thrombin Time (TT), or a quantitative fibrinogen determination. The PTT test is an in vitro laboratory test used to assess the intrinsic coagulation pathway and monitor heparin therapy. Indications 1. The PTT is most commonly used to quantitate the effect of therapeutic unfractionated heparin and to regulate its dosing. Except during transitions between heparin and warfarin therapy, in general both the PTT and PT are not necessary together to assess the effect of anticoagulation therapy. PT and PTT must be justified separately. 2. A PTT may be used to assess patients with signs or symptoms of hemorrhage orthrombosis. For example: • Abnormal bleeding, hemorrhage or hematoma petechiae or other signs ofthrombocytopenia that could be due to Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation • Swollen extremity with or without prior trauma 3. A PTT may be useful in evaluating patients who have a history of a condition known tobe associated with the risk of hemorrhage or thrombosis that is related to the intrinsiccoagulation pathway. Such abnormalities may be genetic or acquired. For example: • Dysfibrinogenemia; Afibrinogenemia (complete) • Acute or chronic liver dysfunction or failure, including Wilson’s disease • Hemophilia • Liver disease and failure; • Infectious processes • Bleeding disorders • Disseminated intravascular coagulation • Lupus erythematosus or other conditions associated with circulating inhibitors, e.g., factor VIII Inhibitor, lupus-like anticoagulant • Sepsis • Von Willebrand’s disease • Arterial and venous thrombosis, including the evaluation of hypercoagulable states • Clinical conditions associated with nephrosis or renal failure • Other acquired and congenital coagulopathies as well as thrombotic states 4. -

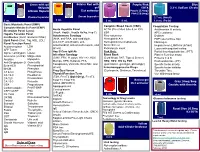

Order of Draw

Green with gel Gold or Red with Purple/Pink Blue 56 Units gel EDTA 3.2% Sodium Citrate Lithium Heparin Clot activator Purple (5.4mg) Pink (10.8mg) Plasma Separator Serum Separator 2.7 mL (Adult) 3 mL 5 mL 3 mL 6 mL 1.8 mL (Peds) Basic Metabolic Panel (BMP) Complete Blood Count (CBC) Coagulation Testing Complete Metabolic Panel (CMP) Acute Hepatitis Panel ACTH (Pre-chilled tube & on ICE) Antithrombin III activity Electrolyte Panel (Lytes) (HepA, HepBc, HepBs Ab/Ag, Hep C) ESR APC resistance Hepatic Function Panel Autoimmune Serology Flow cytometry D-dimer IronStudies (Iron/Transferrin/%Sat) (ANA, anti-DNA, anti-cardiolipin, Hemoglobin A1c FDP (special blue top) Lipid Panel (Chol, Trig, HDL, LDL) anti-CCP, anti-Gliadin, anti- Hemoglobin Electrophoresis Fibrinogen Renal Function Panel mitochondrial, anti-smooth muscle, and Sickle Screen Heparin level (LMWH & Unfract) Acetaminophen LDH others) Reticulocyte count Lupus anticoagulant testing AFP Tumor LH Hep B Core IgM Ab Pink Only: Partial thromboplastin time (PTT) Alpha-1-antitrypsin Lipase Infectious Serology Blood Bank Platelet Function assay Ammonia (on ICE) Magnesium (CMV, EBV, H. pylori, HIV 1+2, HSV, (Cord blood, DAT, Type & Screen) Proteins C & S Amylase Myoglobin Mumps, RPR, Rubeola, FTA, HBV, HCV, HIV by PCR Prothrombin time (PT) Anti-Streptolysin O Osmolality Toxoplasma, Varicella, West Nile, and (quantitative, genotype, phenotype) Specific factor activity Beta-HCG Phenobarbital others) Immunosuppressive Drugs Specific factor inhibitor BHOB Phenytoin Preg Qual Serum (Cyclosporin, -

Transfusion Reaction Evaluation

Lab Dept: Transfusion Services Test Name: TRANSFUSION REACTION EVALUATION General Information Lab Order Codes: TRXR Synonyms: Transfusion Complication Workup; Hemolytic reaction CPT Codes: Dependent on testing involved. Refer to individual serologic procedures. Test Includes: If there is any evidence of significant reaction other than mild urticaria, stop the transfusion but keep normal saline dripping in slowly to keep the I.V. open. Report all reactions to Transfusion Service (612-813-6824/651-220-6558). Clerical Check: Examination of label on blood container(s) and all clerical work and records for possible error, and review possible mirror image or other-side-of-the-coin error. (If one unit is infused into a wrong patient, has another patient/unit been also mixed up?) Visible Plasma Hemoglobin: Examination of prereaction and postreaction serum or plasma for hemolysis or jaundice. This should be begun by examination of the postreaction blood sample sent very promptly to the Transfusion Service. Direct antiglobulin test on postreaction specimen. (If positive, it must be compared with a pretransfusion specimen.) ABO/Rh on Post reaction specimen. If the above are negative and there is no suspicion of incompatibility, additional tests are not essential. Minor reactions (e.g., febrile or allergic) need no further work-up. If actual hemolysis is suspected, the following may be done. Blood container, attached transfusion set and intravenous solutions must be sent to Transfusion Service. Culture of remaining donor blood, if: Patient temperature is ≥39ºC Patient’s temperature increases ≥2ºC Patient’s temperature increases ≥1ºC and is associated with chills and rigors. Repeat ABO and Rh typing on patient and donor blood; compare with previous reports. -

Influence of Temperature and Storage Duration on Measurement of Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time, Ddimers, Fibrinogen, Prot

International Journal of Laboratory Hematology The Official journal of the International Society for Laboratory Hematology ORIGINAL ARTICLE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LABORATORY HEMATOLOGY Influence of temperature and storage duration on measurement of activated partial thromboplastin time, D-dimers, fibrinogen, prothrombin time and thrombin time, in citrate-anticoagulated whole blood specimens Y. ZHAO, G. LV Department of Laboratory SUMMARY Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Introduction: We report the effect of temperature and storage dura- Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, tion on a range of haematological analytes: activated partial throm- China boplastin time (APTT), D-dimers, fibrinogen (Fbg), prothrombin Correspondence: time (PT) and thrombin time (TT). All analytes were measured Garcia Lv, Department of using a Sysmex CA7000 System with SIEMENS reagents. Laboratory Medicine, The First Methods: One hundred and sixty patients were divided into two Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, groups: samples from group A (80 patients) were used to assess the Hangzhou, China. effect of storage at room temperature (RT) (0, 4, 8 and 24 h), and Tel.: +86-0571-87236380; samples from group B (80 patients) were used to determine the Fax: +86 0571-87236383; effect of storage at 4 °C. Percentage changes compared with base- E-mail: [email protected] line results (T = 0 result) were calculated, and clinically relevant > doi:10.1111/ijlh.12113 differences were defined as a percentage change of 10%. Results: Changes in APTT, D-dimer, Fbg, PT and TT results following ° Received 24 January 2013; 4, 8 and 24 h storage were statistically significant at RT and 4 C. accepted for publication For D-dimer, Fbg, PT and TT at both RT and 4 °C, the mean percent- 15 April 2013 age changes after all storage periods were <10%, but for APTT, the mean percentage change following 24 h storage was >10% and Keyword exceeded the analytical within-batch imprecision. -

The Acute Effect of Erythropoietin on Mean Platelet Volume Levels

Original Article / Özgün Araştırma DOI: 10.4274/haseki.3370 Med Bull Haseki 2016;54:199-206 The Acute Effect of Erythropoietin on Mean Platelet Volume Levels during Hypoxia Reoxygenation Injury in Rats Farelerde Hipoksi Reoksijenasyon Hasarında Eritropoietinin Ortalama Trombosit Hacim Düzeyleri Üzerindeki Akut Etkisi Constantinos Tsompos, Constantinos Panoulis*, Konstantinos Toutouzas**, Aggeliki Triantafyllou***, George Zografos**, Apostolos Papalois**** Mesologi County Hospital, Clinic of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mesologi, Greece *Aretaieion Hospital, Clinic of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Athens, Greece **Ippokrateion Hospital, Clinic of Surgery, Athens, Greece ***Athens University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Biologic Chemistry, Athens, Greece ****ELPEN Pharmaceuticals, S.A. Inc., Co, Experimental Research Centre, Pikermi, Greece Abs tract Öz Aim: This biomedical study tested the effect of erythropoietin (Epo) Giriş:Bu deneysel çalışmada, eritropoietinin (Epo) etkisi fare modelinde, in rat model, especially in a hypoxia-reoxygenation one. The trend of özellikle bir hipoksi-reoksijenasyon protokolü dahilinde incelendi. Bu this factor was evaluated hematologically using serum mean platelets molekülün etkisi, kan ortalama trombosit düzeyleri (MPV) kullanılarak volume (MPV) values. hematolojik olarak incelendi. Methods: Forty rats with a mean mass 247.7 g were used. MPV Yöntemler:Ortalama 247,7 gr ağırlığa sahip 40 adet fare çalışmada values were evaluated at 60 min (for groups A and C) and at 120 kullanıldı. MPV düzeyleri 60 dakikalık (A ve C grupları) ve 120 dakikalık min (for groups B and D) of reoxygenation. Epo was provided only in (B ve D grupları) reoksijenasyonlarla ölçüldü. Sadece C ve D gruplarına groups C and D. Epo verildi. Results:Epo administration non-significantly lowered the MPV levels Bulgular: Epo uygulanması MPV düzeylerini kayda değer olmayan bir by 0.12% +2.13% (p=0.9513).