Order of Draw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

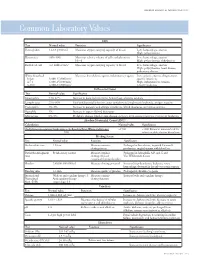

Common Laboratory Values

AmericAn AcAdemy of PediAtric dentistry Reference Manual 2006-2007 Resource Section 251 Common LaboratoryCommon Values Laboratory Values CBC Test Normal value Function Significance Hemoglobin 12-18 g/100 mL Measures oxygen carrying capacity of blood Low: hemorrhage, anemia High: polycythemia Hematocrit 35%-50% Measures relative volume of cells and plasma in Low: hemorrhage, anemia blood High: polycythemia, dehydration Red blood cell 4-6 million/mm3 Measures oxygen-carrying capacity of blood Low: hemorrhage, anemia High: polycythemia, heart disease, pulmonary disease White blood cell Measures host defense against inflammatory agents Low: aplastic anemia, drug toxicity, Infant 8,000-15,000/mm3 specific infections 4-7 y 6,000-15,000/mm3 High: inflammation, trauma, 8-18 y 4,500-13,500/mm3 toxicity, leukemia Differential Count Test Normal value Significance Neutrophils 54%-62% Increase in bacterial infections, hemorrhage, diabetic acidosis Lymphocytes 25%-30% Viral and bacterial infection, acute and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, antigen reaction Eosinophils 1%-3% Increase in parasitic and allergic conditions, blood dyscrasias, pernicious anemia Basophils 1% Increase in types of blood dyscrasias Monocytes 0%-9% Hodgkin’s disease, lipid storage disease, recovery from severe infections, monocytic leukemia Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC) Calculation Normal value Significance (% Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes + % Bands)×Total White Cell Count >1500 <1000 Patient at increased risk for 100 infection; defer elective dental care Bleeding Screen Test -

Coagulation Testing: High Hematocrit-Anticoagulant Adjustment

PREANALYTIC PULSE Coagulation Testing: High Hematocrit-Anticoagulant Adjustment In 1980, CLSI released H21-A4 guidelines for coagulation testing, which included the recommendation to adjust/correct the amount of citrate in blue-top evacuated blood collection tubes for patients presenting hematocrits greater than 55%. In addition to the CLSI guidelines, the CAP hematology checklist HEM.22830 includes the question, “Are there documented guidelines for the detection and special handling of specimens with elevated hematocrits?” Principle The adjustment is to assure the plasma:anticoagulant ratio (not the blood:anticoagulant ratio) stays consistent. A patient with high hematocrit, greater than 55%, will result in less plasma after centrifugation. The plasma fraction will contain an increased concentration of sodium citrate anticoagulant. The increased concentration may result in falsely prolonged test results for Prothrombin Time (PT) and Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT). Formula 1. To calculate the corrected 3.2% sodium citrated whole blood for hematocrit > 55%, adjust the citrate to the proper volume with the following formula: -3 C = (1.85 x 10 )(100-HCT)(Vblood) Where: C = volume of sodium citrate required for that volume of blood HCT = patient’s hematocrit V = volume of blood required in the blood collection tube (example if a 3mL tube is used the blood draw volume is 2.7mL) 1.85 x 10-3 is a constant (considering the citrate volume, blood volume, and citrate concentration). 2. Example: Patient has a Hct of 60% and the patient’s blood will be drawn into a 3mL VACUETTE® sodium citrate (blue-top) blood collection tube. Adjustment of the sodium citrate volume is calculated as: C = (1.85 x 10-3)(100-60)(2.7mL) C = 0.20mL (rounded up from 01.998mL) Remove: 0.30 - 0.20 = 0.10mL of sodium citrate to be removed (0.30 is the difference between the total tube volume of 3.0mL and the blood drawn into the tube of 2.7mL) Method The instructions to prepare an adjusted sodium citrate tube are to be documented in the Laboratory Standard Operating Procedures. -

Laboratory Testing for Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis and Management

Test Guide Laboratory Testing for Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis and Management Chronic kidney disease is defined as abnormalities of kidney prone to error due to inaccurate timing of blood sampling, structure or function, present for greater than 3 months, incomplete urine collection over 24-hours, or over collection with implications for health.1 Diagnostic criteria include of urine beyond 24-hours.2,3 a decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) or presence Given that direct measurement of GFR may be problematic, of 1 or more other markers of kidney damage.1 Markers of eGFR, using either creatinine- or cystatin C-based kidney damage include a histologic abnormality, structural measurements, is most commonly used to diagnose CKD in abnormality, history of kidney transplantation, abnormal urine clinical practice. sediment, tubular disorder-caused electrolyte abnormality, or an increased urinary albumin level (albuminuria). Creatinine-Based eGFR This Test Guide discusses the use of laboratory tests that GFR is typically estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease 4 may aid in identifying chronic kidney disease and monitoring Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. The CKD-EPI and managing disease progression, comorbidities, and equation uses serum-creatinine measurements and the complications. The tests discussed include measurement patient’s age (≥18 years old), sex, and race (African American and estimation of GFR as well as markers of kidney damage. vs non−African American). Creatinine-based eGFR is A list of applicable tests is provided in the Appendix. The recommended by the Kidney Disease Improving Global information is provided for informational purposes only and Outcomes (KDIGO) 2012 international guideline for initial is not intended as medical advice. -

Wellness Labs Explanation of Results

WELLNESS LABS EXPLANATION OF RESULTS BASIC METABOLIC PANEL BUN – Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) is a waste product of protein breakdown and is produced when excess protein in your body is broken down and used for energy. BUN levels greater than 50 mg/dL generally means that the kidneys are not functioning normally. Abnormally low BUN levels can be seen with malnutrition and liver failure. Creatinine – a waste product of normal muscle activity. High creatinine levels are most commonly seen in kidney failure and can also been seen with hyperthyroidism, conditions of overgrowth of the body, rhabdomyolysis, and early muscular dystrophy. Low creatinine levels can indicate low muscle mass associated with malnutrition and late-stage muscular dystrophy. Glucose – a simple sugar that serves as the main source of energy in the body. High glucose levels (hyperglycemia) is usually associated with prediabetes and can also occur with severe stress on the body such as surgery or events like stroke or trauma. High levels can also be seen with overactive thyroid, pancreatitis, or pancreatic cancer. Low glucose levels can occur with underactive thyroid and rare insulin- secreting tumors. Electrolytes – Sodium, Calcium, Potassium, Chloride, and Carbon Dioxide are all included in this category. Sodium – high levels of sodium can be seen with dehydration, excessive thirst, and urination due to abnormally low levels of antidiuretic hormone (diabetes insipidus) as well as with excessive levels of cortisol in the body (Cushing syndrome). Low levels of sodium can be seen with congestive heart failure, cirrhosis of the liver, kidney failure, and the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH). -

Role of Real-Time / Accurate Diagnostic Testing in Patient Blood Management Programs

ROLE OF REAL-TIME / ACCURATE DIAGNOSTIC TESTING IN PATIENT BLOOD MANAGEMENT PROGRAMS POINT-OF-CARE TESTING “Diagnostic testing is an essential component of Patient Blood Management. The accurate assessment of the true causes of bleeding dysfunction facilitates the employment of evidence based, goal directed therapy to rapidly prevent and treat excess blood loss. “ Sherri Ozawa RN, Clinical Director, Institute of Patient Blood Management, Englewood Hospital Medical Center, Englewood, New Jersey. PATIENT BLOOD MANAGEMENT Interdisciplinary Managing Blood Conservation Anemia Modalities “The timely application of evidence based medical and surgical concepts designed to manage IMPROVED anemia, optimize hemostasis, and PATIENT minimize blood loss in order to OUTCOMES improve patient outcomes.” SABM© 2018 - Society for the Advancement of Blood Management (SABM.org) Optimizing Patient-Centered Coagulation Decision Making Point-of-care testing forms an integral part of PBM, enabling accurate and real-time diagnosis of anemia and bleeding and facilitating precise and targeted hemostatic intervention. 1 Conventional coagulation tests are unable to provide needed information on actual bleeding risk/defects 1, thus delaying appropriate and targeted treatment. Slow turnaround times for laboratory-based conventional coagulation tests are one of the major drivers of empirical treatment regimens, which inevitably result in some patients receiving unnecessary, inappropriate and avoidable transfusions, with associated increased morbidity and mortality, and -

Prothrombin Time (PT) Be Kept in Constant and Incubation Temperature at Step 3, Start Stop Watch , Mix in a Water Bath ( 37°C ) (LIQUID REAGENT) 36.5-37.5°C

components of any other kit with different lot numbers. temperature 15 minutes prior to testing. Throughout testing all test tubes, syringes and pipettes 2. Pre-warm PT reagent at 37°C for 5 minutes. should be plastic. 3. Pipette 100µl of PT reagent to each tube. Throughout testing all test tubes, incubation time should 4. Add 50 µl of sample, controls to the tubes prepared in Prothrombin Time (PT) be kept in constant and incubation temperature at step 3, start stop watch , mix in a water bath ( 37°C ) (LIQUID REAGENT) 36.5-37.5°C. for 8 seconds , then record the time required for clot For In-Vitro diagnostic use only If testing is delayed for more than 4 hours, plasma may formation . be stored at 2-8°C. B.Automated Method Store at: 2-8°C Each laboratory should establish a Quality Control To perform this test, refer to the appropriate Instrument program that includes both normal and abnormal control Operator’s Manual for detailed instructions. INTENDED USE plasmas to evaluate instrument, reagent tested daily Prothrombin Time (PT) is commonly used for screening for prior to performing tests on patient plasmas. Monthly RESULTS extrinsic factor deficiency, monitoring oral anticoagulant quality control charts are recommended to determine Clot time of the test Prothrombin Time plasma therapy and quantitative determination of the extrinsic the mean and standard deviation of each of the daily = Ratio (PTR) Clot time of the control coagulation factors. control plasma. All assays should include controls, and if plasma any of the controls are outside the established reference INR = PTRISI PRINCIPLE ranges, then the assay should be considered invalid and Example: for a PTR of 2.0 and an ISI of 1.0 Tissue thromboplastin, in the presence of calcium ions and no patient results should be reported. -

Global Assays of Hemostasis in the Diagnostics of Hypercoagulation and Evaluation of Thrombosis Risk Elena N Lipets1 and Fazoil I Ataullakhanov1,2,3,4,5,6*

Lipets and Ataullakhanov Thrombosis Journal (2015) 13:4 DOI 10.1186/s12959-015-0038-0 REVIEW Open Access Global assays of hemostasis in the diagnostics of hypercoagulation and evaluation of thrombosis risk Elena N Lipets1 and Fazoil I Ataullakhanov1,2,3,4,5,6* Abstract Thrombosis is a deadly malfunctioning of the hemostatic system occurring in numerous conditions and states, from surgery and pregnancy to cancer, sepsis and infarction. Despite availability of antithrombotic agents and vast clinical experience justifying their use, thrombosis is still responsible for a lion’s share of mortality and morbidity in the modern world. One of the key reasons behind this is notorious insensitivity of traditional coagulation assays to hypercoagulation and their inability to evaluate thrombotic risks; specific molecular markers are more successful but suffer from numerous disadvantages. A possible solution is proposed by use of global, or integral, assays that aim to mimic and reflect the major physiological aspects of hemostasis process in vitro. Here we review the existing evidence regarding the ability of both established and novel global assays (thrombin generation, thrombelastography, thrombodynamics, flow perfusion chambers) to evaluate thrombotic risk in specific disorders. The biochemical nature of this risk and its detectability by analysis of blood state in principle are also discussed. We conclude that existing global assays have a potential to be an important tool of hypercoagulation diagnostics. However, their lack of standardization currently impedes their application: different assays and different modifications of each assay vary in their sensitivity and specificity for each specific pathology. In addition, it remains to be seen how their sensitivity to hypercoagulation (even when they can reliably detect groups with different risk of thrombosis) can be used for clinical decisions: the risk difference between such groups is statistically significant, but not large. -

64Th Annual SSC Meeting, in Conjunction with the 2018 ISTH Congress in Dublin, Ireland Meeting Minutes Standing Committees Coagulation Standards Committee

64th Annual SSC meeting, in conjunction with the 2018 ISTH Congress in Dublin, Ireland Meeting Minutes Standing Committees Coagulation Standards Committee............................................................... 3 Subcommittees Animal, Cellular and Molecular Models ........................................................ 6 Biorheology .................................................................................................. 9 Control of Anticoagulation ............................................................................ 15 Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation ...................................................... 20 Factor VIII, Factor IX and Rare Coagulation Disorders ................................ 23 Factor XI and the Contact System ............................................................... 27 Factor XIII and Fibrinogen ............................................................................ 30 Fibrinolysis ................................................................................................... 34 Genomics in Thrombosis and Hemostasis ................................................... 38 Hemostasis and Malignancy ........................................................................ 47 Lupus Anticoagulant/Phospholipid Dependent Antibodies ........................... 51 Pediatric and Neonatal Hemostasis and Thrombosis ................................... 57 Perioperative and Critical Care Thrombosis and Hemostasis ...................... 66 Plasma Coagulation Inhibitors ..................................................................... -

Severity of Anaemia Has Corresponding Effects on Coagulation Parameters of Sickle Cell Disease Patients

diseases Article Severity of Anaemia Has Corresponding Effects on Coagulation Parameters of Sickle Cell Disease Patients Samuel Antwi-Baffour 1,* , Ransford Kyeremeh 1 and Lawrence Annison 2 1 Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, School of Allied Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana, P.O. Box KB 143 Accra, Ghana; [email protected] 2 Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, School of Allied Health Sciences, Narh-Bita College, P.O. Box Co1061 Tema, Ghana; [email protected] * Correspondence: s.antwi-baff[email protected] Received: 31 July 2019; Accepted: 18 October 2019; Published: 17 December 2019 Abstract: Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited condition characterized by chronic haemolytic anaemia. SCD is associated with moderate to severe anaemia, hypercoagulable state and inconsistent platelet count and function. However, studies have yielded conflicting results with regards to the effect of anaemia on coagulation in SCD. The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of anaemia severity on selected coagulation parameters of SCD patients. Four millilitres of venous blood samples were taken from the participants (SCD and non-SCD patients) and used for analysis of full blood count and coagulation parameters. Data was analysed using SPSS version-16. From the results, it was seen that individuals with SCD had a prolonged mean PT, APTT and high platelet count compared to the controls. There was also significant difference in the mean PT (p = 0.039), APTT (p = 0.041) and platelet count (p = 0.010) in HbSS participants with severe anaemia. Mean APTT also showed significant difference (p = 0.044) with severe anaemia in HbSC participants. -

Blood and Immunity

Chapter Ten BLOOD AND IMMUNITY Chapter Contents 10 Pretest Clinical Aspects of Immunity Blood Chapter Review Immunity Case Studies Word Parts Pertaining to Blood and Immunity Crossword Puzzle Clinical Aspects of Blood Objectives After study of this chapter you should be able to: 1. Describe the composition of the blood plasma. 7. Identify and use roots pertaining to blood 2. Describe and give the functions of the three types of chemistry. blood cells. 8. List and describe the major disorders of the blood. 3. Label pictures of the blood cells. 9. List and describe the major disorders of the 4. Explain the basis of blood types. immune system. 5. Define immunity and list the possible sources of 10. Describe the major tests used to study blood. immunity. 11. Interpret abbreviations used in blood studies. 6. Identify and use roots and suffixes pertaining to the 12. Analyse several case studies involving the blood. blood and immunity. Pretest 1. The scientific name for red blood cells 5. Substances produced by immune cells that is . counteract microorganisms and other foreign 2. The scientific name for white blood cells materials are called . is . 6. A deficiency of hemoglobin results in the disorder 3. Platelets, or thrombocytes, are involved in called . 7. A neoplasm involving overgrowth of white blood 4. The white blood cells active in adaptive immunity cells is called . are the . 225 226 ♦ PART THREE / Body Systems Other 1% Proteins 8% Plasma 55% Water 91% Whole blood Leukocytes and platelets Formed 0.9% elements 45% Erythrocytes 10 99.1% Figure 10-1 Composition of whole blood. -

Common Laboratory Tests

Common Laboratory Tests BMP (Basic Metabolic Panel): A BMP is a common blood chemistry test that measures your sugar level, electrolyte balance, and kidney function. CBC (Complete Blood Count): A common blood test that helps determine an individual’s general health status. It evaluates hemoglobin, hematocrit, white blood cells, red blood cells, red blood cell indices, and platelets. It can be used as a tool to help diagnose various conditions, such as anemia, infection, inflammation, bleeding disorder, or leukemia. CMP (Complete Metabolic Panel): A CMP is similar to a BMP, in that it measures your sugar level, electrolyte balance, kidney function, but it also measures liver function. ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate): A non-specific blood test that is used to help detect inflammation. It is said to be non-specific because an elevated result often indicates inflammation but does not tell exactly where the inflammation is in the body or what is causing it. It is typically used in conjunction with other testing. Ferritin: A blood test that assesses a person’s iron stores in the body. The test is sometimes ordered with an iron test and a TIBC (Total Iron Binding Capacity) to detect the presence and severity of iron deficiency or iron overload. FT4 (Free Thyroxine): Free T4 is a blood test used to help evaluate thyroid function and diagnose thyroid diseases usually after discovering that the TSH level is abnormal. FT3 (Free Triiodothyronine): Free T3 is a blood test used to assess thyroid function. It is primarily used to help diagnose hyperthyroidism and may be ordered to help monitor treatment of a person with a known thyroid disorder. -

Pneumomediastinum in a Patient with Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome

IMAGES IN MEDICINE Pneumomediastinum in a Patient with Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome MARC J. VECCHIO, MD; WILLIAM D. BINDER, MD, FACEP 48 49 EN CASE PRESENTATION Figure 1. (A) Red arrows illustrating extensive pneumomediastinum and pneumo- A 23-year-old man with a past medical retroperitoneum; (B) illustrating air extending into the neck and spinal canal. history of cannabinoid hyperemesis syn- drome presented to the emergency depart- A B ment with 1 week of nausea, emesis and poor oral intake. Prior to presentation, the patient had been treated in the emer- gency department several times for intrac- table vomiting. The patient reported he was a daily long-term user of marijuana cigarettes. On presentation, the patient was afebrile with a pulse of 117 beats per minute, res- pirations of 20 per minute, blood pressure of 111/79 and oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. Physical examination revealed a thin man with eructation and subcutane- ous crepitation over the neck and thorax. Lung sounds were clear to auscultation bilaterally. Laboratory testing revealed a pH of 7.26, anion gap of 33, blood-urea nitrogen of 107 mg/dL and a newly ele- vated creatinine of 13.01 mg/dL. Nota- bly, the patient had normal labs with a creatinine of 0.84 mg/dL during a similar presentation for intractable vomiting one month prior to presentation. Chest X-ray showed evidence of subcutaneous gas and pneumomediastinum. Computed tomog- raphy (CT) of the chest and abdomen with intravenous contrast revealed pneu- momediastinum and pneumoretroperito- neum with extension into the spinal canal (Figure 1).