Johannes Muller Stosch,Conductor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday Playlist

October 31, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal.” — Igor Stravinsky Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Tchaikovsky Moscow Radio 00:01 Buy Now! Glinka Waltz Fantasie Harmonia Mundi 288 114 N/A Awake! Symphony/Fedoseyev 00:12 Buy Now! Schubert String Quartet No. 1, D. 18 Verdi Quartet Haenssler Classic 98.329 4010276009580 Rubinstein, 00:28 Buy Now! Piano Sonata No. 3 in F, Op. 41 Leslie Howard Hyperion 66017 034571160177 Anton 01:01 Buy Now! Salieri Concerto in C for Flute and Oboe Dohn/Sous/Wurttemberg Ch. Orch./Faerber Vox 7198 04716371982 01:22 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Ballet Music ~ The Maid of Orleans Royal Opera House Covent Garden/Davis Philips 422 845 028942284524 01:38 Buy Now! Rachmaninoff The Isle of the Dead, Op. 29 Royal Philharmonic/Litton Virgin 90830 075679083029 02:00 Buy Now! Balakirev Chopin Suite Singapore Symphony/Hoey Hong Kong 8.220324 N/A 02:22 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 Pine/Gottingen Symphony/Mueller Cedille 144 765131914420 02:49 Buy Now! Canning Fantasy on a Hymn by Justin Morgan Suzuki/Orlovsky/Indianapolis SO/Leppard Decca 458 157 028945845725 03:01 Buy Now! Bach Prelude and Fugue in G, BWV 541 Läubin Brass Ensemble DG 423 988 028942398825 String Sextet in D minor, Op. 70 "Souvenir of 03:09 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Bashmet/Gutman/Borodin Quartet EMI 49775 077774977524 Florence" 03:43 Buy Now! Grieg Lyric Suite, Op. 54 Malmö Symphony/Engeset Naxos 8.508015 747313801534 04:01 Buy Now! Strauss, R. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 59,1939

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 1492 FIFTY—NINTH SEASON, 1939-194o CONCERT BULLETIN OF THE Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor RICHARD BURGIN, Assistant Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by JOHN N. BURK COPYRIGHT, 1939, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. ERNEST B. DANE • • President HENRY B. SAWYER Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE . • Treasurer HENRY B. CABOT M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE ERNEST B. DANE ROGER I. LEE ALVAN T. FULLER RICHARD C. PAINE JEROME D. GREENE HENRY B. SAWYER N. PENROSE HALT OWELL EDWARD A. TAFT BENTLEY W. WARREN G. E. JUDD, Manager C. W. SPALDING, Assistant Manager ( 289 ) Complete FIDUCIARY SERVICE /^INDIVIDUALS The fiduciary services of Old Colony Trust Company available to individuals are many and varied. We cite some of the fiduciary capacities in which we act. Executor and Administrator We settle estates as Executor and Administrator. Trustee We act as Trustee under wills and under voluntary or living trusts. Agent We act as Agent for those who wish to be relieved of the care of their investments. The officers of Old Colony Trust Company are always glad to discuss estate and property matters with you and point out if and where our services are applicable. Old Colony Trust Company 17 COURT STREET, BOSTON Member of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation ^Allied w/'MThe First National Bank ^Boston [ 290] ,1 FIFTY-NINTH SEASON - NINETEEN HUNDRED THIRTY-NINE AND FORTY Seventh Programme FRIDAY AFTERNOON, December i, at 2:30 o'clock SATURDAY EVENING, December 2, at 8:15 o'clock IGOR STRAVINSKY Conducting Stravinsky "Jeu de Cartes" (Card Game, Ballet in Three Deals) (First performances at these concerts) Stravinsky Capriccio for Orchestra with Piano Solo I. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

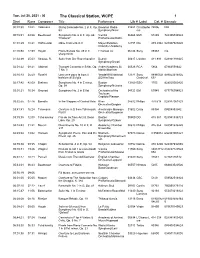

Tue, Jul 20, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 13:01 Volkmann String Serenade No. 2 in F, Op. Bavarian Radio 01487 Christopho 74506 N/A 63 Symphony/Nicol rus 00:15:3144:28 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 Vienna 06364 EMI 57445 724355744524 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Rattle 01:01:29 18:21 Hoffmeister Oboe Concerto in C Mayer/Potsdam 12355 DG 479 2942 028947929420 Chamber Academy 01:20:5012:59 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 49 in C Emanuel Ax 06244 Sony 89363 n/a sharp minor 01:34:49 25:03 Strauss, R. Suite from Der Rosenkavalier Detroit 00617 London 411 893 028941189325 Symphony/Dorati 02:01:2208:21 Albinoni Trumpet Concerto in B flat, Op. Andre/Academy St. 00526 RCA 5864 07863558642 7 No. 3 Martin/Marriner 02:10:43 05:59 Rossini Una voce poco fa from Il Yende/RAI National 12979 Sony 88985321 889853216925 barbiere di Siviglia SO/Armiliato Classical 692 02:17:4242:09 Brahms Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Boston 13169 BSO 1703 828020003425 Op. 98 Symphony/Nelsons 03:01:21 30:34 Gounod Symphony No. 2 in E flat Orchestra of the 04723 EMI 63949 077776394923 Toulouse Capitole/Plasson 03:32:5507:46 Borodin In the Steppes of Central Asia Kirov 08532 Philips 470 618 028947061823 Orchestra/Gergiev 03:41:4116:24 Telemann Overture in D from Tafelmusik, Amsterdam Baroque 01602 Erato 85394 08908853942 Part II Orchestra/Koopman 03:59:3512:08 Tchaikovsky Pas de six from Act III, Swan Boston 00500 DG 415 367 028941536723 Lake, Op. -

A B C a B C D a B C D A

24 go symphonyorchestra chica symphony centerpresent BALL SYMPHONY anne-sophie mutter muti riccardo orchestra symphony chicago 22 september friday, highlight season tchaikovsky mozart 7:00 6:00 Mozart’s fiery undisputed queen ofviolin-playing” ( and Tchaikovsky’s in beloved masterpieces, including Rossini’s followed by Riccardo Muti leading the Chicago SymphonyOrchestra season. Enjoy afestive opento the preconcert 2017/18 reception, proudly presents aprestigious gala evening ofmusic and celebration The Board Women’s ofthe Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Gala package guests will enjoy postconcert dinner and dancing. rossini Suite from Suite 5 No. Concerto Violin to Overture C P s oncert reconcert Reception Turkish The Sleeping Beauty Concerto. The SleepingBeauty William Tell conducto The Times . Anne-Sophie Mutter, “the (Turkish) William Tell , London), performs London), , media sponsor: r violin Overture 10 Concerts 10 Concerts A B C A B 5 Concerts 5 Concerts D E F G H I 8 Concerts 5 Concerts E F G H 5 Concerts 6 Conc. 5 Concerts THU FRI FRI SAT SAT SUN TUE 8:00 1:30 8:00 2017/18 8:00 8:00 3:00 7:30 ABCABCD ABCDAAB Riccardo Muti conductor penderecki The Awakening of Jacob 9/23 9/26 Anne-Sophie Mutter violin tchaikovsky Violin Concerto schumann Symphony No. 2 C A 9/28 9/29 Riccardo Muti conductor rossini Overture to William Tell 10/1 ogonek New Work world premiere, cso commission A • F A bruckner Symphony No. 4 (Romantic) A Alain Altinoglu conductor prokoFIEV Suite from The Love for Three Oranges Sandrine Piau soprano poulenc Gloria Michael Schade tenor gounod Saint Cecilia Mass 10/5 10/6 Andrew Foster-Williams 10/7 C • E B bass-baritone B • G Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe chorus director 10/26 10/27 James Gaffigan conductor bernstein Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront James Ehnes violin barber Violin Concerto B • I A rachmaninov Symphonic Dances Sir András Schiff conductor mozart Serenade for Winds in C Minor 11/2 11/3 and piano bartók Divertimento for String Orchestra 11/4 11/5 A • G C bach Keyboard Concerto No. -

Thu, Jun 17, 2021 - the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

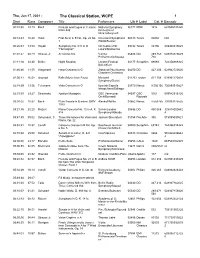

Thu, Jun 17, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 12:13 Bach Prelude and Fugue in C minor, National Symphony 06771 MSR 1312 681585131220 BWV 546 Orchestra of Ukraine/Leytush 00:14:4310:20 Holst First Suite in E flat, Op. 28 No. Cleveland Symphonic 00335 Telarc 80038 N/A 1 Winds/Fennell 00:26:0333:54 Haydn Symphony No. 031 in D, Orchestra of St. 09192 Telarc 80156 089408015625 "Hornsignal" Luke's/Mackerras 01:01:2708:49 Strauss Jr. Accelerations Vienna 05888 DG 289 459 028945973029 Philharmonic/Maazel 730 01:11:1634:30 Bellini Night Shadow London Festival 04177 Seraphim 69089 724356908925 Ballet/Kern 01:46:4611:55 Wagenseil Harp Concerto in G Zabaleta/Paul Kuentz 04250 DG 427 206 028942720626 Chamber Orchestra 02:00:1116:58 Gounod Ballet Music from Faust Montreal 01125 London 411 708 028941170828 Symphony/Dutoit 02:18:0913:56 Telemann Viola Concerto in G Kyselak/Capella 03370 Naxos 8.550156 730099515627 Istropolitana/Edlinger 02:33:0529:27 Stravinsky Apollon Musagete CBC Vancouver 04097 CBC 5161 059582516126 Orch/Bernardi Records 03:04:0216:37 Bach Flute Sonata in B minor, BWV Alanko/Mattila 04662 Naxos 8.553755 730099475525 1030 03:21:3925:20 Mozart Piano Concerto No. 12 in A, K. Serkin/London 00486 DG 400 068 325914000682 414 Symphony/Abbado 4 03:47:5909:02 Schumann, C. Three Romances for Violin and Jochum/Silverstein 01354 Pro Arte 395 015095039521 Piano, Op. 22 03:58:3110:37 Corelli Concerto Grosso in B flat, Op. -

Igor Stravinsky Y Robert Craft: Expositions and Developments, Ed

MO I IGORNO STRAVINSKY I GRÁ FI CO UNRUSOENSAN PETERSBURGO: EL PÁJARO DE FUEGO* Stephen Walsh• El período de formación de Stravinsky, tan descuidado por la mayor parte de los estudio- sos de su obra, es importante para comprender el estilo maduro del compositor a partir de Petrushka. El autor del artículo pasa revista a las obras tempranas de Stravinsky, sobre todo la Sinfonía en mi bemol, Scherzo fantastique, Feu d’artifice, El Pájaro de Fuego o El Ruise- ñor. En este panorama, es necesario contemplar El Pájaro de Fuego como una obra de sín- tesis que cierra una época, y no, como a menudo se hace, como inicio del estilo maduro. Desde este punto de vista, el autor estudia la confluencia en estas obras tempranas de la tradición representada por Rimsky, su maestro, a la vez académica y progresista, y la tradi- ción heterodoxa, antiacadémica y con profundas raíces en la cultura tradicional y en el len- guaje ruso de Mussorgsky, además de otras influencias, como la del impresionismo francés o incluso la del “detestado” estilo de Scriabin. De la primera aprenderá las herramientas necesarias para el dominio de la arquitectura musical y de la orquestación y la composición de la textura; de la segunda, un uso de la armonía y la disonancia no sometido a las con- venciones de la gramática tonal y un ritmo que vive de la agrupación irregular de pulsos y que le permitirá desarrollar su técnica constructiva basada en el uso de células manipula- bles que se rearticulan de manera diversa. Para la mayor parte de los estudiosos de Stravinsky, las obras que éste com- puso antes de El pájaro de fuego tienen una importancia comparativamente menor que las obras tempranas de otros compositores. -

Stravinsky and the Octatonic: a Reconsideration

Stravinsky and the Octatonic: A Reconsideration Dmitri Tymoczko Recent and not-so-recent studies by Richard Taruskin, Pieter lary, nor that he made explicit, conscious use of the scale in many van den Toorn, and Arthur Berger have called attention to the im- of his compositions. I will, however, argue that the octatonic scale portance of the octatonic scale in Stravinsky’s music.1 What began is less central to Stravinsky’s work than it has been made out to as a trickle has become a torrent, as claims made for the scale be. In particular, I will suggest that many instances of purported have grown more and more sweeping: Berger’s initial 1963 article octatonicism actually result from two other compositional tech- described a few salient octatonic passages in Stravinsky’s music; niques: modal use of non-diatonic minor scales, and superimposi- van den Toorn’s massive 1983 tome attempted to account for a tion of elements belonging to different scales. In Part I, I show vast swath of the composer’s work in terms of the octatonic and that the rst of these techniques links Stravinsky directly to the diatonic scales; while Taruskin’s even more massive two-volume language of French Impressionism: the young Stravinsky, like 1996 opus echoed van den Toorn’s conclusions amid an astonish- Debussy and Ravel, made frequent use of a variety of collections, ing wealth of musicological detail. These efforts aim at nothing including whole-tone, octatonic, and the melodic and harmonic less than a total reevaluation of our image of Stravinsky: the com- minor scales. -

Igor Stravinsky

A PORTRAIT Igor Stravinsky 1882–1971 Igor Stravinsky: A Portrait Preface Among the carefully adapted transcriptions of conversations between the veteran Stravinsky and Robert Craft, there is one especially telling passage. Referring to his 1920 ballet Pulcinella, the composer recalls the reaction to his arrangements of Pergolesi and other eighteenth-century musicians: People who had never heard of, or cared about, the originals cried ‘sacrilege’: ‘The classics are ours. Leave the classics alone.’ To them all my answer was and is the same: You ‘respect’, but I love. A great genius’s love for all his models is what lies at the heart of Stravinsky’s creativity. (It is worth noting that although he was apt to put inverted commas around the word ‘heart’, Stravinsky leaves the word ‘love’ to stand unqualified in the above quotation.) He made everything he touched become his own, whether it was the lush nationalist influence of his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov, or the extreme refinement of Anton Webern, whose music he discovered so late in life. No theme was deemed too cheap or outlandish a subject for transformation, and his inspiration was wide-ranging. Prokofiev thought him a disgraceful thief for pilfering other ballet composers’ ideas in Apollo, but Stravinsky’s genuine admiration for composers as unlikely as Gounod and Delibes was unlimited. Hungarian and Greek folk music, the antics of the music hall 4 Igor Stravinsky: A Portrait entertainer Little Tich, and the jazz trumpeting of Shorty Rogers: all these were grist to his creative mill. As the awed conductors who welcomed the eighty-year-old Stravinsky back to Russia so eloquently wrote at the time, the only figure with whom he could be compared was Picasso. -

Igor Stravinsky, One of the Greatest Masters of Modern Music, Was Born in Oranienbaum, Near St

FROM: AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE 890 Broadway New York, New York 10003 (212) 477-3030 Kelly Ryan IGOR (FEDOROVITCH) STRAVINSKY Igor Stravinsky, one of the greatest masters of modern music, was born in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, on June 17, 1882. The son of a famous bass singer at the Imperial Opera, Feodor Stravinsky, he was raised in an artistic atmosphere. He studied law until age nineteen, when Rimsky- Korsakov in Heidelberg encouraged him to study composition seriously and he studied theory with Kalafati. In 1907, Stravinsky studied with Rimsky-Korsakov in St. Petersburg and on January 22, 1908, his first symphony, which showed a mastery of technique, was performed in St. Petersburg. This was followed on February 29, by his critically successful set of songs for mezzo-soprano and orchestra, Le Faune et la Bergere. In celebration of Maxmillian Steinberg's marriage to Rimsky-Korsakov's daughter (June 17, 1908), Stravinsky wrote an orchestral fantasy, Feu d'artifice, and when Rimsky-Korsakov died a few days later, he wrote a threnody as a tribute. Stravinsky's next orchestral work, Scherzo fantastique, was performed in St. Petersburg (February 6, 1909) and the famous impresario, Diaghilev, heard it and commissioned Stravinsky to write a work on a Russian subject. The result was the production of the first of Stravinsky's ballet masterpieces, L'Oiseau de feu (Paris, June 15, 1910) and the beginning of the successful collaboration between the composer and producer. Stravinsky’s association with Diaghilev concentrated his activities in Paris and he moved there in 1911. His second ballet for the impresario, Petrouchka, (Paris, June 13, 1911), was a great success and was so new and original that it marked a turning point in 20th century modernism. -

Ofmusic PROGRAM

•• SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA LARRY RACHLEFF, music director Saturday, March 10, 2012 8:00 p.m. Stude Concert Hall • • l~ . the f RICE UNIVERSITY ~~ ofMusic PROGRAM Nuages (Clouds) & Fetes (Festivals) Claude Debussy from Nocturnes (1862-1918) 1 Feu d'artifice (Fireworks), Op. 4 Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Toccata e Corale (2010, Premiere)* Brian Nelson (b. 1977) David In-Jae Cho, conductor INTERMISSION Symphony No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 39 Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) Andante, ma non troppo - Allegro energico Andante (ma non troppo lento) Scherzo. Allegro Finale (quasi una fantasia). Andante -Allegro molto * Brian Nelson is the recipient ofthe 2011 Paul and Christiane Cooper Prize in Music Composition, awarded to him for this composition. ~ Paul Cooper was a founding faculty member of the Shepherd School and composer-in-residence ofRice University. The reverberative acoustics ofStude Concert Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. ... The taking ofphotographs and use of recording equipment are prohibited. SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Violin I Cello Clarinet Timpani Ritchie Zah, Emma Bobbs, Camilo Davila Robert Frisk concertmaster principal Lin Ma Lindsey Pietrek ANNE AND CHARLES ANNETTE AND HUGH Colin Ryan DUNCAN CHAIR GRAGG CHAIR Juan Olivares LeTriel White Joanna Park Hellen Weberpal Percussion Micah Wright Meghan Henniger Jesse Christeson Robert Frisk Chau! Yang Matthew Kufchak Bass Clarinet Robert J. Garza III Micah Ringham Benjamin Stoehr Juan Olivares Robert McCullagh -

SD SYMPHONY 2021 Pressrelease 4.1.2020 FINAL

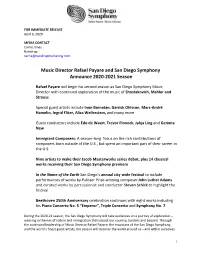

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 6, 2020 MEDIA CONTACT Carrie Jones Raindrop [email protected] Music Director Rafael Payare and San Diego Symphony Announce 2020-2021 Season Rafael Payare will begin his second season as San Diego Symphony Music Director with continued exploration of the music of Shostakovich, Mahler and Strauss Special guest artists include Inon Barnatan, Garrick Ohlsson, Marc-André Hamelin, Ingrid Fliter, Alisa Weilerstein, and many more Guest conductors include Edo de Waart, Trevor Pinnock, Jahja Ling and Gemma New Immigrant Composers: A season-long focus on the rich contributions of composers born outside of the U.S., but spent an important part of their career in the U.S. Nine artists to make their Jacob Masterworks series debut, plus 14 classical works receiving their San Diego Symphony premiere In the Name of the Earth San Diego’s annual city-wide festival to include performances of works by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer John Luther Adams and curated works by percussionist and conductor Steven Schick to highlight the festival Beethoven 250th Anniversary celebration continues with eight works including his Piano Concerto No. 5 “Emperor”, Triple Concerto and Symphony No. 7 During the 2020-21 season, the San Diego Symphony will take audiences on a journey of exploration – weaving in themes of nature and immigration that impact our country, borders and beyond. Through the continued leadership of Music Director Rafael Payare, the musicians of the San Diego Symphony, and the world’s finest guest artists, the season will discover the world around us—and within ourselves. 1 Payare will conduct nine weeks of concerts in the 2020-21 season, and will continue his focus on works by Strauss and Mahler that push the level of artistry of the orchestra. -

Igor Stravinsky Petrushka

Exiles from Revolution Stravinsky the nationalist Welcome to the new look Soviet Music @ Lewes U3A This term we are going to explore how Soviet music reacted to Russian composers living abroad. Our five sessions will explore: One: Stravinsky the nationalist Two: Prokofiev and machine music Three: Stravinsky’s middle period Four: Rakhmaninov reclaimed Five: Stravinsky’s homecoming and his late period music Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was already living in the west in 1917, and didn’t visit Russia again until 1962. Sergei Rakhmaninov (1873-1943) emigrated soon after the Bolsheviks took power, and never returned. Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) negotiated a leave of absence from revolutionary turmoil, returning in 1936. © 2020 Terry Metheringham [email protected] +44 7528 835 422 Soviet Music: Exiles from Revolution Session 1: Stravinsky the nationalist 2 Introduction: Stravinsky the nationalist Today we will be focusing on Stravinsky’s 1911 ballet Petrushka. We will use it as a launch pad for exploring how Stravinsky’s brand of nationalism was received in the USSR from the early years of the revolution through to the 1960s. We will also hear music by Soviet composers echoing aspects of Petrushka: Prokofiev Russian Overture (1936) Popov Second Symphony “Motherland” (1944) Shchedrin Concerto for Orchestra No. 1 “Naughty Limericks” (1963) The total length of the music in this session is 95 minutes (with an option to reduce that to 70 minutes by only listening to one movement of Popov). © 2020 Terry Metheringham [email protected] +44 7528 835 422 Soviet Music: Exiles from Revolution Session 1: Stravinsky the nationalist 3 Stravinsky background Igor Stravinsky was born into a musical family.