Igor Stravinsky Petrushka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday Playlist

October 31, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal.” — Igor Stravinsky Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Tchaikovsky Moscow Radio 00:01 Buy Now! Glinka Waltz Fantasie Harmonia Mundi 288 114 N/A Awake! Symphony/Fedoseyev 00:12 Buy Now! Schubert String Quartet No. 1, D. 18 Verdi Quartet Haenssler Classic 98.329 4010276009580 Rubinstein, 00:28 Buy Now! Piano Sonata No. 3 in F, Op. 41 Leslie Howard Hyperion 66017 034571160177 Anton 01:01 Buy Now! Salieri Concerto in C for Flute and Oboe Dohn/Sous/Wurttemberg Ch. Orch./Faerber Vox 7198 04716371982 01:22 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Ballet Music ~ The Maid of Orleans Royal Opera House Covent Garden/Davis Philips 422 845 028942284524 01:38 Buy Now! Rachmaninoff The Isle of the Dead, Op. 29 Royal Philharmonic/Litton Virgin 90830 075679083029 02:00 Buy Now! Balakirev Chopin Suite Singapore Symphony/Hoey Hong Kong 8.220324 N/A 02:22 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 Pine/Gottingen Symphony/Mueller Cedille 144 765131914420 02:49 Buy Now! Canning Fantasy on a Hymn by Justin Morgan Suzuki/Orlovsky/Indianapolis SO/Leppard Decca 458 157 028945845725 03:01 Buy Now! Bach Prelude and Fugue in G, BWV 541 Läubin Brass Ensemble DG 423 988 028942398825 String Sextet in D minor, Op. 70 "Souvenir of 03:09 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Bashmet/Gutman/Borodin Quartet EMI 49775 077774977524 Florence" 03:43 Buy Now! Grieg Lyric Suite, Op. 54 Malmö Symphony/Engeset Naxos 8.508015 747313801534 04:01 Buy Now! Strauss, R. -

Artistic Hybridism in Stravinsky's Renard

Russia ‘Reimagined’: Artistic Hybridism in Stravinsky’s Renard (1915 -1916) © 2005 by Helen Kin Hoi Wong In his Souvenir sur Igor Stravinsky , the Swiss novelist Ramuz recalled his first impression of Stravinsky as a Russian man of possessiveness: What I recognized in you was an appetite and feeling for life, a love of all that is living.. The objects that made you act or react were the most commonplace... While others registered doubt or self-distrust, you immediately burst into joy, and this reaction was followed at once by a kind of act of possession, which made itself visible on your face by the appearance of two rather wicked-looking lines at the corner of your mouth. What you love is yours, and what you love ought to be yours. You throw yourself on your prey - you are in fact a man of prey. 1 Ramuz’s comment perhaps explains what make Stravinsky’s musical style so pluralistic - his desire to exploit native materials and adopt foreign things as if his own. When Stravinsky began working on the Russian libretto of Renard in 1915, he was living in Switzerland in exile, leaving France where he had established his career. As a Russian avant-garde composer of extreme folklorism (as demonstrated in the Firebird , Petrushka and the Rite ), Stravinsky was never on edge in France. His growing friendship with famous French artists such as Vati, Debussy, Ravel, Satie, Cocteau and Claudel indicated that he was gradually being perceived as part of the French artistic culture. In fact, this change of perception on Stravinsky was more than socially driven, as his musical language by the end of the War (1918) had clearly transformed to a new type which adhered to the French popular taste (as manifested in L'Histoire du Soldat , Five Easy Pieces and Ragtime ). -

Ballet? Y First the Ballerina Glides Across the Stage, Her Arms M Making Lovely Lines in the Air

My First alle B Album t What is Ballet? Firs The ballerina glides across the stage, her arms My t making lovely lines in the air. A beautiful tune comes from the strings of the large orchestra. She is the Sleeping Beauty: she was put into a allet deep magic sleep by the wicked witch. But she B lbum has now been woken by her handsome prince, A and he dances joyfully with her, athletic and strong. Another time, she is Princess Odette from Swan Lake, and around her the other dancers – swans in white chiffon – weave patterns in time to the music. And yet another time, she is the Sugar Plum Fairy celebrating the joy of Christmas in The Nutcracker. This is ballet, the classical dance that, once seen, is never forgotten. Even though today we have film and video games, ballet is still a powerful vision of beauty and excitement. The dancers use the strength of an athlete, the balance of a gymnast and the sensitivity of a violinist to tell stories through their dancing. Here is some of the best music which has propelled dancers for hundreds of years. 2 Tchaikovsky Swan Lake Stravinsky The Firebird 1 Scene 2:37 3 Scene I. The Firebird’s Dance 1:19 Keyword: Oboe Keyword: Fire Swan Lake is a ballet from Russia about a prince called Siegfried. In the forest he finds A firebird is a brightly coloured magical bird that comes a mysterious lake where swans are swimming, led by a beautiful but sad swan wearing out of the fire. -

College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark D

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Summer 2017 College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music Mark D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Mark D., "College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music" (2017). Dissertations. 132. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark David Taylor A Doctor of Musical Arts Document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE Committee Chair: Dr. Eric Guinivan Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Mary Jean Speare Mr. Foster Beyers Acknowledgments Dr. Robert McCashin, former Director of Orchestras and Professor of Orchestral Conducting at James Madison University (JMU) as well as a co-founder of College Orchestra Directors Association (CODA), served as an important sounding-board as the study emerged. Dr. McCashin was particularly helpful in pointing out the challenges of undertaking such a study. I would have been delighted to have Dr. McCashin serve as the chair of my doctoral committee, but he retired from JMU before my study was completed. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 59,1939

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 1492 FIFTY—NINTH SEASON, 1939-194o CONCERT BULLETIN OF THE Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor RICHARD BURGIN, Assistant Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by JOHN N. BURK COPYRIGHT, 1939, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. ERNEST B. DANE • • President HENRY B. SAWYER Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE . • Treasurer HENRY B. CABOT M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE ERNEST B. DANE ROGER I. LEE ALVAN T. FULLER RICHARD C. PAINE JEROME D. GREENE HENRY B. SAWYER N. PENROSE HALT OWELL EDWARD A. TAFT BENTLEY W. WARREN G. E. JUDD, Manager C. W. SPALDING, Assistant Manager ( 289 ) Complete FIDUCIARY SERVICE /^INDIVIDUALS The fiduciary services of Old Colony Trust Company available to individuals are many and varied. We cite some of the fiduciary capacities in which we act. Executor and Administrator We settle estates as Executor and Administrator. Trustee We act as Trustee under wills and under voluntary or living trusts. Agent We act as Agent for those who wish to be relieved of the care of their investments. The officers of Old Colony Trust Company are always glad to discuss estate and property matters with you and point out if and where our services are applicable. Old Colony Trust Company 17 COURT STREET, BOSTON Member of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation ^Allied w/'MThe First National Bank ^Boston [ 290] ,1 FIFTY-NINTH SEASON - NINETEEN HUNDRED THIRTY-NINE AND FORTY Seventh Programme FRIDAY AFTERNOON, December i, at 2:30 o'clock SATURDAY EVENING, December 2, at 8:15 o'clock IGOR STRAVINSKY Conducting Stravinsky "Jeu de Cartes" (Card Game, Ballet in Three Deals) (First performances at these concerts) Stravinsky Capriccio for Orchestra with Piano Solo I. -

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky Source: http://www.8notes.com/biographies/stravinsky.asp ‘Even during his lifetime, Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was a legendary figure. His once revolutionary work were modern classics, and he influenced three generations of composers and other artists. Cultural giants like Picasso and T. S. Eliot were his friends. President John F. Kennedy honored him at a White House dinner in his eightieth year. 'Stavinsky was born in Oranienbaum, Russia, near St. Petersburg (Leningrad), grew up in a musical atmosphere, and studied with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. He had his first important opportunity in 1909, when the impresario Sergei Diaghilev heard his music. Diaghilev was the director of the Russian Ballet, an extremely influential troupe which employed great painters as well as important dances, choreographers, and composers. Diaghilev first asked Stravinsky to orchestrate some piano pieces by Chopin as ballet music and then, in 1910, commissioned an original ballet, The Firebird, which was immensely successful. A year later (1911), Stravinsky's second ballet, Petrushka, was performed, and Stravinsky was hailed as a modern master. When his third ballet, The Rite of Spring (a savage, brutal portrayal of a prehistoric ritual in which a young girl is sacrificed to the god of Spring.), had its premiere in Paris in 1913, a riot erupted in the audience--spectators were shocked and outraged by its pagan primitivism, harsh dissonance, percussiveness, and pounding rhythms--but it too was recognized as a masterpiece and influenced composers all over the world. 'During World War I, Stravinsky sought refuge in Switzerland; after the armistice, he moved to France, his home until the onset of World War II, when he came to the United States. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 125, 2005-2006

Tap, tap, tap. The final movement is about to begin. In the heart of This unique and this eight-acre gated final phase is priced community, at the from $1,625 million pinnacle of Fisher Hill, to $6.6 million. the original Manor will be trans- For an appointment to view formed into five estate-sized luxury this grand finale, please call condominiums ranging from 2,052 Hammond GMAC Real Estate to a lavish 6,650 square feet of at 617-731-4644, ext. 410. old world charm with today's ultra-modern comforts. BSRicJMBi EM ;\{? - S'S The path to recovery... a -McLean Hospital ', j Vt- ^Ttie nation's top psychiatric hospital. 1 V US NeWS & °r/d Re >0rt N£ * SE^ " W f see «*££% llffltlltl #•&'"$**, «B. N^P*^* The Pavijiorfat McLean Hospital Unparalleled psychiatric evaluation and treatment Unsurpassed discretion and service BeJmont, Massachusetts 6 1 7/855-3535 www.mclean.harvard.edu/pav/ McLean is the largest psychiatric clinical care, teaching and research affiliate R\RTNERSm of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate of Massachusetts General Hospital HEALTHCARE and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #78 bump-bump bump-bump bump-bump There are lots of reasons to choose Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like less invasive and more permanent cardiac arrhythmia treatments. And other innovative ways we're tending to matters of the heart in our renowned catheterization lab, cardiac MRI and peripheral vascular diseases units, and unique diabetes partnership with Joslin Clinic. From cardiology and oncology to sports medicine and gastroenterology, you'll always find care you can count on at BIDMC. -

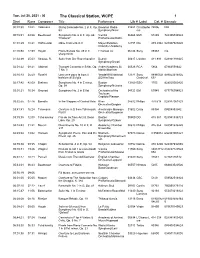

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jul 20, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 13:01 Volkmann String Serenade No. 2 in F, Op. Bavarian Radio 01487 Christopho 74506 N/A 63 Symphony/Nicol rus 00:15:3144:28 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 Vienna 06364 EMI 57445 724355744524 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Rattle 01:01:29 18:21 Hoffmeister Oboe Concerto in C Mayer/Potsdam 12355 DG 479 2942 028947929420 Chamber Academy 01:20:5012:59 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 49 in C Emanuel Ax 06244 Sony 89363 n/a sharp minor 01:34:49 25:03 Strauss, R. Suite from Der Rosenkavalier Detroit 00617 London 411 893 028941189325 Symphony/Dorati 02:01:2208:21 Albinoni Trumpet Concerto in B flat, Op. Andre/Academy St. 00526 RCA 5864 07863558642 7 No. 3 Martin/Marriner 02:10:43 05:59 Rossini Una voce poco fa from Il Yende/RAI National 12979 Sony 88985321 889853216925 barbiere di Siviglia SO/Armiliato Classical 692 02:17:4242:09 Brahms Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Boston 13169 BSO 1703 828020003425 Op. 98 Symphony/Nelsons 03:01:21 30:34 Gounod Symphony No. 2 in E flat Orchestra of the 04723 EMI 63949 077776394923 Toulouse Capitole/Plasson 03:32:5507:46 Borodin In the Steppes of Central Asia Kirov 08532 Philips 470 618 028947061823 Orchestra/Gergiev 03:41:4116:24 Telemann Overture in D from Tafelmusik, Amsterdam Baroque 01602 Erato 85394 08908853942 Part II Orchestra/Koopman 03:59:3512:08 Tchaikovsky Pas de six from Act III, Swan Boston 00500 DG 415 367 028941536723 Lake, Op. -

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

Edinburgh International Festival 1962

WRITING ABOUT SHOSTAKOVICH Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Edinburgh Festival 1962 working cover design ay after day, the small, drab figure in the dark suit hunched forward in the front row of the gallery listening tensely. Sometimes he tapped his fingers nervously against his cheek; occasionally he nodded Dhis head rhythmically in time with the music. In the whole of his productive career, remarked Soviet Composer Dmitry Shostakovich, he had “never heard so many of my works performed in so short a period.” Time Music: The Two Dmitrys; September 14, 1962 In 1962 Shostakovich was invited to attend the Edinburgh Festival, Scotland’s annual arts festival and Europe’s largest and most prestigious. An important precursor to this invitation had been the outstanding British premiere in 1960 of the First Cello Concerto – which to an extent had helped focus the British public’s attention on Shostakovich’s evolving repertoire. Week one of the Festival saw performances of the First, Third and Fifth String Quartets; the Cello Concerto and the song-cycle Satires with Galina Vishnevskaya and Rostropovich. 31 DSCH JOURNAL No. 37 – July 2012 Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya in Edinburgh Week two heralded performances of the Preludes & Fugues for Piano, arias from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Sixth, Eighth and Ninth Symphonies, the Third, Fourth, Seventh and Eighth String Quartets and Shostakovich’s orches- tration of Musorgsky’s Khovanschina. Finally in week three the Fourth, Tenth and Twelfth Symphonies were per- formed along with the Violin Concerto (No. 1), the Suite from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Three Fantastic Dances, the Cello Sonata and From Jewish Folk Poetry. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Vi Saint Petersburg International New Music Festival Artistic Director: Mehdi Hosseini

VI SAINT PETERSBURG INTERNATIONAL NEW MUSIC FESTIVAL ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: MEHDI HOSSEINI 21 — 25 MAY, 2019 facebook.com/remusik.org vk.com/remusikorg youtube.com/user/remusikorg twitter.com/remusikorg instagram.com/remusik_org SPONSORS & PARTNERS GENERAL PARTNERS 2019 INTERSECTIO A POIN OF POIN A The Organizing Committee would like to express its thanks and appreciation for the support and assistance provided by the following people: Eltje Aderhold, Karina Abramyan, Anna Arutyunova, Vladimir Begletsov, Alexander Beglov, Sylvie Bermann, Natalia Braginskaya, Denis Bystrov, Olga Chukova, Evgeniya Diamantidi, Valery Fokin, Valery Gergiev, Regina Glazunova, Andri Hardmeier, Alain Helou, Svetlana Ibatullina, Maria Karmanovskaya, Natalia Kopich, Roger Kull, Serguei Loukine, Anastasia Makarenko, Alice Meves, Jan Mierzwa, Tatiana Orlova, Ekaterina Puzankova, Yves Rossier, Tobias Roth Fhal, Olga Shevchuk, Yulia Starovoitova, Konstantin Sukhenko, Anton Tanonov, Hans Timbremont, Lyudmila Titova, Alexei Vasiliev, Alexander Voronko, Eva Zulkovska. 1 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall 4 Masterskaya M. K. Anikushina FESTIVAL CALENDAR Dekabristov St., 37 Vyazemsky Ln., 8 mariinsky.ru vk.com/sculptorstudio 2 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre 5 “Lumiere Hall” creative space TUESDAY / 21.05 19:00 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall Fontanka River Embankment 49, Lit A Obvodnogo Kanala emb., 74А ensemble für neue musik zürich (Switzerland) alexandrinsky.ru lumierehall.ru 3 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov 6 The Concert Hall “Jaani Kirik” Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Dekabristov St., 54A Glinka St., 2, Lit A jaanikirik.ru WEDNESDAY / 22.05 13:30 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov conservatory.ru Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Composer meet-and-greet: Katharina Rosenberger (Switzerland) 16:00 Lumiere Hall Marcus Weiss, Saxophone (Switzerland) Ensemble for New Music Tallinn (Estonia) 20:00 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre Around the Corner (Spain, Switzerland) 4 Vyazemsky Ln.