Igor Stravinsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday Playlist

October 31, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal.” — Igor Stravinsky Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Tchaikovsky Moscow Radio 00:01 Buy Now! Glinka Waltz Fantasie Harmonia Mundi 288 114 N/A Awake! Symphony/Fedoseyev 00:12 Buy Now! Schubert String Quartet No. 1, D. 18 Verdi Quartet Haenssler Classic 98.329 4010276009580 Rubinstein, 00:28 Buy Now! Piano Sonata No. 3 in F, Op. 41 Leslie Howard Hyperion 66017 034571160177 Anton 01:01 Buy Now! Salieri Concerto in C for Flute and Oboe Dohn/Sous/Wurttemberg Ch. Orch./Faerber Vox 7198 04716371982 01:22 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Ballet Music ~ The Maid of Orleans Royal Opera House Covent Garden/Davis Philips 422 845 028942284524 01:38 Buy Now! Rachmaninoff The Isle of the Dead, Op. 29 Royal Philharmonic/Litton Virgin 90830 075679083029 02:00 Buy Now! Balakirev Chopin Suite Singapore Symphony/Hoey Hong Kong 8.220324 N/A 02:22 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 Pine/Gottingen Symphony/Mueller Cedille 144 765131914420 02:49 Buy Now! Canning Fantasy on a Hymn by Justin Morgan Suzuki/Orlovsky/Indianapolis SO/Leppard Decca 458 157 028945845725 03:01 Buy Now! Bach Prelude and Fugue in G, BWV 541 Läubin Brass Ensemble DG 423 988 028942398825 String Sextet in D minor, Op. 70 "Souvenir of 03:09 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Bashmet/Gutman/Borodin Quartet EMI 49775 077774977524 Florence" 03:43 Buy Now! Grieg Lyric Suite, Op. 54 Malmö Symphony/Engeset Naxos 8.508015 747313801534 04:01 Buy Now! Strauss, R. -

Pre Competitve Classical Top 15

PRE COMPETITVE CLASSICAL TOP 15 1. BRADY FARRAR VARIATION FROM SATANELLA - Stars Dance Company 2. CATHERINE ROWLAND DULCINEA VARIATION DON QUIXOTE - Magda Aunon School of Classical Ballet 3. ASHLEY VALLEJO KITRI VARIATION FROM DON QUIXOTE - Stars Dance Company 4. SCARLETT BARONE BLACK SWAN VARIATION - Impac Youth Ensemble 5. ROMI BRITTON VARIATION FROM LA ESMERALDA - Meg Segreto's Dance Center 6. ERICA AVILA VARIATION FROM LA ESMERALDA - Meg Segreto's Dance Center 7. PABLO MANZO THE NUTCRACKER MALE VARIATION - Vladimir Issaev School of Classical Ballet 8. DESTANYE DIAZ VARIATION FROM GRADUATION BALL - Stars Dance Company 9. MONIQUE MADURO LA FILLE MAL GARDEE – Pointe Centro de Danzas 10. MADISON BROWN PRINCESS FLORINE VARIATION SLEEPING BEAUTY – Lents Dance Company 11. VERONICA MERINO LA FILLE MAL GARDEE - Pointe Centro de Danzas 12. KACI WILKINSON SILVER FAIRY VARIATION SLEEPING BEAUTY – Backstage Dance Academy 13. KAITLYN SILOT DON QUIXOTE VARIATION - Artistic Dance Center 14. SORA TERAMOTO BLUE BIRD VARIATION - Baller Elite Dance Studio 15. RACHEL LEON LA FILLE MAL GARDEE - Stars Dance Company PRE COMPETITVE CONTEMPORARY TOP 15 1. DIANA POMBO BECOMING - TPS (The Pombo Sisters) 2. BRADY FARRAR RESILIENT - Stars Dance Company 3. DESTANYE DIAZ IMPACT - Stars Dance Company 4. ASHLEY VALLEJO TAKE ME - Stars Dance Company 5. RACHEL LEON MOONLIGHT SONATA - Stars Dance Company 6. MADISON BROWN NOUVEAU TANGO - Lents Dance Company 7. ERICA AVILA MIND HEIST - Meg Segreto's Dance Center 8. SCARLETT BARONE HAND IN HAND - Impac Youth Center 9. MONIQUE MADURO CONFUSED - Pointe Centro de Danzas 10. CATHERINE ROWLAND THE GENIE - Magda Aunon School of Classical Ballet 11. ANGELINA SIERRA EVERYTHING MUST CHANGE - Ballet East 12. -

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2008 Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective Alejandro Marcelo Drago University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Drago, Alejandro Marcelo, "Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective" (2008). Dissertations. 1107. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved: May 2008 COPYRIGHT BY ALEJANDRO MARCELO DRAGO 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2008 ABSTRACT INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. -

San Francisco Symphony 2019–2020 Season Concert Calendar

Contact: Public Relations San Francisco Symphony (415) 503-5474 [email protected] www.sfsymphony.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / MARCH 12, 2019 SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY 2019–2020 SEASON CONCERT CALENDAR PLEASE NOTE: Subscription packages for the San Francisco Symphony’s 2019–20 season go on sale TUESDAY, March 12 at 10 am at www.sfsymphony.org/MTT25, (415) 864-6000, and at the Davies Symphony Hall Box Office, located on Grove Street between Franklin and Van Ness. Discover how to receive free concerts with your subscription package. For additional details and questions visit www.sfsymphony.org/MTT25. All concerts are at Davies Symphony Hall, 201 Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco, unless otherwise noted. OPENING NIGHT GALA Wednesday, September 4, 2019 at 8:00 pm Michael Tilson Thomas conductor and piano San Francisco Symphony ALL SAN FRANCISCO CONCERT with MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Thursday, September 5, 2019 at 8 pm Saturday, September 7, 2019 at 8 pm Michael Tilson Thomas conductor Alina Ming Kobialka violin Hannah Tarley violin San Francisco Symphony BERLIOZ Overture to Benvenuto Cellini, Opus 23 SAINT-SAËNS Introduction and Rondo capriccioso, Opus 28 RAVEL Tzigane GERSHWIN Second Rhapsody for Orchestra with Piano BRITTEN Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Purcell San Francisco Symphony 2019-20 Season Calendar – Page 2 of 22 SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS CONDUCTING Thursday, September 12, 2019 at 8 pm Friday, September 13, 2019 at 8 pm Saturday, September 14, 2019 at 8 pm Sunday, September 15, 2019 at 2 pm Michael Tilson Thomas conductor San Francisco Symphony MAHLER Symphony No. 6 in A minor SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS CONDUCTING Thursday, September 19, 2019 at 2 pm Friday, September 20, 2019 at 8 pm Saturday, September 21, 2019 at 8 pm Sunday, September 22, 2019 at 2 pm Michael Tilson Thomas conductor Daniil Trifonov piano San Francisco Symphony John ADAMS New Work [SFS Co-commission, World Premiere] RACHMANINOFF Piano Concerto No. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 59,1939

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 1492 FIFTY—NINTH SEASON, 1939-194o CONCERT BULLETIN OF THE Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor RICHARD BURGIN, Assistant Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by JOHN N. BURK COPYRIGHT, 1939, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. ERNEST B. DANE • • President HENRY B. SAWYER Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE . • Treasurer HENRY B. CABOT M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE ERNEST B. DANE ROGER I. LEE ALVAN T. FULLER RICHARD C. PAINE JEROME D. GREENE HENRY B. SAWYER N. PENROSE HALT OWELL EDWARD A. TAFT BENTLEY W. WARREN G. E. JUDD, Manager C. W. SPALDING, Assistant Manager ( 289 ) Complete FIDUCIARY SERVICE /^INDIVIDUALS The fiduciary services of Old Colony Trust Company available to individuals are many and varied. We cite some of the fiduciary capacities in which we act. Executor and Administrator We settle estates as Executor and Administrator. Trustee We act as Trustee under wills and under voluntary or living trusts. Agent We act as Agent for those who wish to be relieved of the care of their investments. The officers of Old Colony Trust Company are always glad to discuss estate and property matters with you and point out if and where our services are applicable. Old Colony Trust Company 17 COURT STREET, BOSTON Member of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation ^Allied w/'MThe First National Bank ^Boston [ 290] ,1 FIFTY-NINTH SEASON - NINETEEN HUNDRED THIRTY-NINE AND FORTY Seventh Programme FRIDAY AFTERNOON, December i, at 2:30 o'clock SATURDAY EVENING, December 2, at 8:15 o'clock IGOR STRAVINSKY Conducting Stravinsky "Jeu de Cartes" (Card Game, Ballet in Three Deals) (First performances at these concerts) Stravinsky Capriccio for Orchestra with Piano Solo I. -

Rimsky-Korsakov Overture and Suites from the Operas

CHAN 10369(2) X RIMSKY-KORSAKOV OVERTURE AND SUITES FROM THE OPERAS Scottish National Orchestra Neeme Järvi 21 CCHANHAN 110369(2)X0369(2)X BBOOK.inddOOK.indd 220-210-21 221/8/061/8/06 110:02:490:02:49 Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908) COMPACT DISC ONE 1 Overture to ‘May Night’ 9:06 Suite from ‘The Snow Maiden’ 13:16 2 I Beautiful Spring 4:28 Drawing by Ilya Repin /AKG Images 3 II Dance of the Birds 3:18 4 III The Procession of Tsar Berendey 1:49 5 IV Dance of the Tumblers 3:40 Suite from ‘Mlada’ 19:18 6 I Introduction 3:19 7 II Redowa. A Bohemian Dance 3:55 8 III Lithuanian Dance 2:24 9 IV Indian Dance 4:21 10 V Procession of the Nobles 5:18 Suite from ‘Christmas Eve’ 29:18 11 Christmas Night – 6:15 12 Ballet of the Stars – 5:21 13 Witches’ sabbath and ride on the Devil’s back – 5:30 14 Polonaise – 5:47 15 Vakula and the slippers 6:23 TT 71:30 Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov, 1888 3 CCHANHAN 110369(2)X0369(2)X BBOOK.inddOOK.indd 22-3-3 221/8/061/8/06 110:02:420:02:42 COMPACT DISC TWO Rimsky-Korsakov: Overture and Suites from the Operas Musical Pictures from ‘The Tale of Tsar Saltan’ 21:29 1 I Tsar’s departure and farewell 4:57 2 II Tsarina adrift at sea in a barrel 8:43 Among Russian composers of the same year he was posted to the clipper Almaz on 3 III The three wonders 7:48 generation as Tchaikovsky, who were which he sailed on foreign service for almost prominent in the latter part of the three years, putting in at Gravesend (with a 4 The Flight of the Bumble-bee 3:22 nineteenth century, Nikolai Andreyevich visit to London), cruising the Atlantic coasts Interlude, Act III, from The Tale of Tsar Saltan Rimsky-Korsakov is unrivalled in his of North and South America, the Cape Verde mastery of orchestral resource. -

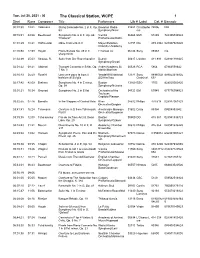

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jul 20, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 13:01 Volkmann String Serenade No. 2 in F, Op. Bavarian Radio 01487 Christopho 74506 N/A 63 Symphony/Nicol rus 00:15:3144:28 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 Vienna 06364 EMI 57445 724355744524 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Rattle 01:01:29 18:21 Hoffmeister Oboe Concerto in C Mayer/Potsdam 12355 DG 479 2942 028947929420 Chamber Academy 01:20:5012:59 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 49 in C Emanuel Ax 06244 Sony 89363 n/a sharp minor 01:34:49 25:03 Strauss, R. Suite from Der Rosenkavalier Detroit 00617 London 411 893 028941189325 Symphony/Dorati 02:01:2208:21 Albinoni Trumpet Concerto in B flat, Op. Andre/Academy St. 00526 RCA 5864 07863558642 7 No. 3 Martin/Marriner 02:10:43 05:59 Rossini Una voce poco fa from Il Yende/RAI National 12979 Sony 88985321 889853216925 barbiere di Siviglia SO/Armiliato Classical 692 02:17:4242:09 Brahms Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Boston 13169 BSO 1703 828020003425 Op. 98 Symphony/Nelsons 03:01:21 30:34 Gounod Symphony No. 2 in E flat Orchestra of the 04723 EMI 63949 077776394923 Toulouse Capitole/Plasson 03:32:5507:46 Borodin In the Steppes of Central Asia Kirov 08532 Philips 470 618 028947061823 Orchestra/Gergiev 03:41:4116:24 Telemann Overture in D from Tafelmusik, Amsterdam Baroque 01602 Erato 85394 08908853942 Part II Orchestra/Koopman 03:59:3512:08 Tchaikovsky Pas de six from Act III, Swan Boston 00500 DG 415 367 028941536723 Lake, Op. -

STRAVINSKY's NEO-CLASSICISM and HIS WRITING for the VIOLIN in SUITE ITALIENNE and DUO CONCERTANT by ©2016 Olivia Needham Subm

STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT By ©2016 Olivia Needham Submitted to the graduate degree program in School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird ________________________________________ Véronique Mathieu ________________________________________ Bryan Haaheim ________________________________________ Philip Kramp ________________________________________ Jerel Hilding Date Defended: 04/15/2016 The Dissertation Committee for Olivia Needham certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird Date Approved: 04/15/2016 ii ABSTRACT This document is about Stravinsky and his violin writing during his neoclassical period, 1920-1951. Stravinsky is one of the most important neo-classical composers of the twentieth century. The purpose of this document is to examine how Stravinsky upholds his neoclassical aesthetic in his violin writing through his two pieces, Suite italienne and Duo Concertant. In these works, Stravinsky’s use of neoclassicism is revealed in two opposite ways. In Suite Italienne, Stravinsky based the composition upon actual music from the eighteenth century. In Duo Concertant, Stravinsky followed the stylistic features of the eighteenth century without parodying actual music from that era. Important types of violin writing are described in these two works by Stravinsky, which are then compared with examples of eighteenth-century violin writing. iii Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was born in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov) in Russia near St. -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Saturday, April 18, 2015 8 p.m. 7:15 p.m. – Pre-performance discussion Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts www.quickcenter.com ~INTERMISSION~ COPLAND ................................ Two Pieces for Violin and Piano (1926) K. LEE, MCDERMOTT ANNE-MARIE MCDERMOTT, piano STRAVINSKY ................................Concertino for String Quartet (1920) DAVID SHIFRIN, clarinet AMPHION STRING QUARTET, HYUN, KRISTIN LEE, violin SOUTHORN, LIN, MARICA AMPHION STRING QUARTET KATIE HYUN, violin DAVID SOUTHORN, violin COPLAND ............................................Sextet for Clarinet, Two Violins, WEI-YANG ANDY LIN, viola Viola, Cello, and Piano (1937) MIHAI MARICA, cello Allegro vivace Lento Finale STRAVINSKY ..................................... Suite italienne for Cello and Piano SHIFRIN, HYUN, SOUTHORN, Introduzione: Allegro moderato LIN, MARICA, MCDERMOTT Serenata: Larghetto Aria: Allegro alla breve Tarantella: Vivace Please turn off cell phones, beepers, and other electronic devices. Menuetto e Finale Photographing, sound recording, or videotaping this performance is prohibited. MARICA, MCDERMOTT COPLAND ...............................Two Pieces for String Quartet (1923-28) AMPHION STRING QUARTET, HYUN, SOUTHORN, LIN, MARICA STRAVINSKY ............................Suite from Histoire du soldat for Violin, Clarinet, and Piano (1918-19) The Soldier’s March Music to Scene I Music to Scene II Tonight’s performance is sponsored, in part, by: The Royal March The Little Concert Three Dances: Tango–Waltz–Ragtime The Devil’s Dance Great Choral Triumphal March of the Devil K. LEE, SHIFRIN, MCDERMOTT Notes on the Program by DR. RICHARD E. RODDA Two Pieces for String Quartet Aaron Copland Suite italienne for Cello and Piano Born November 14, 1900 in Brooklyn, New York. Igor Stravinsky Died December 2, 1990 in North Tarrytown, New York. -

Anne-Lise Gastaldi, Piano ENGLISH – FRANÇAIS Contrasts

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971), L’Histoire du Soldat, Three pieces for clarinet solo Béla Bartók (1881-1945), Contrastes, Sonata for solo violin Béla Bartók, Contrastes for clarinet, violin and piano (1938) 1. Verbunkos 5’30 2. Pihenö 4’42 3. Sebes 6’56 Igor Stravinsky, Three pieces for clarinet solo (1919) 4. Molto tranquillo 2’19 5. [-] 1’09 6. [-] 1’28 Béla Bartók, Sonata for solo violin (1944) 7. Tempo di ciaccona 10’53 8. Fuga (risoluto, non troppo vivo) 5’05 9. Melodia (adagio) 7’30 10. Presto 5’57 Igor Stravinsky, L’Histoire du Soldat for violin, clarinet and piano (1919) 11. Marche du soldat 1’38 12. Le violon du soldat 2’35 13. Petit concert 2’54 14. Tango / Valse / Ragtime 6’27 15. Danse du diable 1’23 David Lefèvre, violin Florent Héau, clarinet Anne-Lise Gastaldi, piano ENGLISH – FRANÇAIS Contrasts When he wrote about learned music being enriched by traditional music, Bartók almost always cited Stravinsky as a major influence and predecessor. The Rite of Springhad a profound impact on Bartók and his contemporaries: Bartók felt its principles of composition showed the influence of Russian folk music. Stravinsky’s attraction to popular culture, however, was mainly literary: as a child he had immersed himself in the world of Russian folk tales in his father’s vast library. One of these tales, part of the Afanassiev collection, inspired Stravinsky during his Swiss exile in 1917 to write L’Histoire du Soldat (The Soldier’s Tale) with his friend the librettist Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz. Other works written in the same period (Les Noces, Pribaoutki, Renard and Les Berceuses du Chat) stemmed from musical sources, and in particular from the Kivievsky collection of popu- lar songs which Stravinsky had brought from Kiev.