09-08 Music from Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday Playlist

October 31, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal.” — Igor Stravinsky Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Tchaikovsky Moscow Radio 00:01 Buy Now! Glinka Waltz Fantasie Harmonia Mundi 288 114 N/A Awake! Symphony/Fedoseyev 00:12 Buy Now! Schubert String Quartet No. 1, D. 18 Verdi Quartet Haenssler Classic 98.329 4010276009580 Rubinstein, 00:28 Buy Now! Piano Sonata No. 3 in F, Op. 41 Leslie Howard Hyperion 66017 034571160177 Anton 01:01 Buy Now! Salieri Concerto in C for Flute and Oboe Dohn/Sous/Wurttemberg Ch. Orch./Faerber Vox 7198 04716371982 01:22 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Ballet Music ~ The Maid of Orleans Royal Opera House Covent Garden/Davis Philips 422 845 028942284524 01:38 Buy Now! Rachmaninoff The Isle of the Dead, Op. 29 Royal Philharmonic/Litton Virgin 90830 075679083029 02:00 Buy Now! Balakirev Chopin Suite Singapore Symphony/Hoey Hong Kong 8.220324 N/A 02:22 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 Pine/Gottingen Symphony/Mueller Cedille 144 765131914420 02:49 Buy Now! Canning Fantasy on a Hymn by Justin Morgan Suzuki/Orlovsky/Indianapolis SO/Leppard Decca 458 157 028945845725 03:01 Buy Now! Bach Prelude and Fugue in G, BWV 541 Läubin Brass Ensemble DG 423 988 028942398825 String Sextet in D minor, Op. 70 "Souvenir of 03:09 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Bashmet/Gutman/Borodin Quartet EMI 49775 077774977524 Florence" 03:43 Buy Now! Grieg Lyric Suite, Op. 54 Malmö Symphony/Engeset Naxos 8.508015 747313801534 04:01 Buy Now! Strauss, R. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 40,1920

EMPIRE THEATRE .... FALL RIVER Sunday Afternoon, December 26, 1920, at 3.00 Under the Auspices of the Woman's Club of Fall River ^1p %% 3T ^•^-.••frfr Anw % BOSTON >mi\ SYMPHONY ORCHESTRH INCORPORATED FORTIETH SEASON 1920-1921 PRoGRHttttE i ! 3 * - 5 STEINWAY & SONS STEINERT JEWETT WOODBURY STEINWAY PIANOLA WEBER PIANOLA STECK PIANOLA WHEELOCK PIANOLA STROUD PIANOLA Most Complete Stock of Records in New England Fa!) River Address 52 No, Main Street EMPIRE THEATRE FALL RIVER FORTIETH SEASON, 1920-1921 INCORPORATED PIERRE MONTEUX, Conductor SUNDAY AFTERNOON, DECEMBER 26, at 3.00 WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1920, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INCORPORATED THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. FREDERICK P. CABOT President GALEN L. STONE Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE Treasurer ALFRED L. AIKEN FREDERICK E. LOWELL FREDERICK P. CABOT ARTHUR LYMAN ERNEST B. DANE HENRY B. SAWYER M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE GALEN L. STONE JOHN ELLERTON LODGE BENTLEY W. WARREN W. H. BRENNAN, Manager G. E. JUDD. Assistant Manager ^hp dm* ^HE INSTRUMENT OF THE IMMORTALS LISZT, greatest of all pianists, preferred -i the Steinway. Wagner, Berlioz, Rubinstein and a host of master-musicians esteemed it more highly than any other instrument. It is these traditions that have inspired Steinway achievement and raised this piano to its artistic pre-eminence which is today recognized throughout the world. 107-109 East 14th Street New York City Subway Express Stations at the Door REPRESENTED BY THE FOREMOST DEALERS EVERYWHERE Fortieth Season, 1920-1921 ' PIERRE MONTEUX, Conductor Violins. Burgin, R. Hoffmann, J. Gerardi, A. Sauvlet, H. -

Oct 12 to 18.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Oct. 12 - 18, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 10/12/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto for violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes & 6:13 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 27 6:29 AM Arcangelo Corelli Concerto Grosso No. 6 6:44 AM Johann Nepomuk Hummel Gesellschafts Rondo 7:02 AM Michel Richard Delalande Suite No. 12 7:16 AM Muzio Clementi Piano Sonata 7:33 AM Mademoiselle Duval Suite from the Ballet "Les Génies" 7:46 AM Georg (Jiri Antonin) Benda Sinfonia No. 9 8:02 AM Johann David Heinichen Concerto for fl,ob,vln,clo,theorbo,st,bc 8:12 AM Franz Joseph Haydn String Quartet 8:31 AM Joan Valent Quatre Estacions a Mallorca 9:05 AM Ralph Vaughan Williams Symphony No. 3 9:41 AM Robert Schumann Fantasiestucke 9:52 AM Ralph Vaughan Williams Silent Noon 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart LA CLEMENZA DI TITO: Overture 10:06 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Violin Sonata No. 27 10:24 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Flute & Harp Concerto (mvmt 2) 10:34 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento No. 1 10:49 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sonata for 2 pianos 11:01 AM Mark Volker Young Prometheus 11:39 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Paris Quartet No. 2:TWV 43: a 3 12:00 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven Wellington's Victory (Battle Symphony) 12:14 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 6 12:28 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Wine, Women & Song 12:40 PM John Ireland Piano Trio No. 2 12:54 PM Michael Kamen CRUSOE: Marooned 1:02 PM Mark O'Connor Trio No. -

Orchestra - Workshop Pieces 2021: All Orchestras Taking Part in the Competition Are Asked to Prepare Their Respective Compulsory Piece for the First Workshop

Orchestra - Workshop Pieces 2021: All orchestras taking part in the Competition are asked to prepare their respective compulsory piece for the first workshop. For the second workshop, please select one piece from the list of your respective category.Y ou may also choose a piece from your additional program. This piece, however, needs to be confirmed by the Artistic Director first. All orchestras taking part in the Celebration are invited to prepare two pieces from the list of your respective category. You may also choose a piece from your additional program. This piece, however, needs to be confirmed by the Artistic Director first. Symphony Orchestra: Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op.93, IV. Allegro vivace Hector Berlioz: Béatrice et Bénédict: Overture Ludwig van Beethoven: One movement from 1st, 2nd,4th or 5th Symphony Ludwig van Beethoven: One movement from Egmont, Coriolan or Fidelio Overture Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 1 in B flat major, Op. 38, 3rd movement, Scherzo Molto Vivace Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy: Symphony No.3 in a minor Op. 56 (“Scottish”) 2nd movement, Vivace non troppo Antonín Dvořák: Slavonic Dances No. 3 and 8 Chamber Orchestra: Franz Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 104 in D major, I. Adagio – Allegro or IV. Finale: Spiritoso Franz Schubert: One movement from Symphony No.5 in B flat major (D 485) Joseph Haydn: One movement from Symphony No.43 in Efl at major Hob.I: 43 (“Mercury”) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: One movement from Symphony Nr. 29 in A major, KV 201 Béla Bartók: Rumanian Folk Dances String Orchestra: Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy: Sinfonia No. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 59,1939

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 1492 FIFTY—NINTH SEASON, 1939-194o CONCERT BULLETIN OF THE Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor RICHARD BURGIN, Assistant Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by JOHN N. BURK COPYRIGHT, 1939, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. ERNEST B. DANE • • President HENRY B. SAWYER Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE . • Treasurer HENRY B. CABOT M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE ERNEST B. DANE ROGER I. LEE ALVAN T. FULLER RICHARD C. PAINE JEROME D. GREENE HENRY B. SAWYER N. PENROSE HALT OWELL EDWARD A. TAFT BENTLEY W. WARREN G. E. JUDD, Manager C. W. SPALDING, Assistant Manager ( 289 ) Complete FIDUCIARY SERVICE /^INDIVIDUALS The fiduciary services of Old Colony Trust Company available to individuals are many and varied. We cite some of the fiduciary capacities in which we act. Executor and Administrator We settle estates as Executor and Administrator. Trustee We act as Trustee under wills and under voluntary or living trusts. Agent We act as Agent for those who wish to be relieved of the care of their investments. The officers of Old Colony Trust Company are always glad to discuss estate and property matters with you and point out if and where our services are applicable. Old Colony Trust Company 17 COURT STREET, BOSTON Member of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation ^Allied w/'MThe First National Bank ^Boston [ 290] ,1 FIFTY-NINTH SEASON - NINETEEN HUNDRED THIRTY-NINE AND FORTY Seventh Programme FRIDAY AFTERNOON, December i, at 2:30 o'clock SATURDAY EVENING, December 2, at 8:15 o'clock IGOR STRAVINSKY Conducting Stravinsky "Jeu de Cartes" (Card Game, Ballet in Three Deals) (First performances at these concerts) Stravinsky Capriccio for Orchestra with Piano Solo I. -

National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine Theodore Kuchar, Conductor Alexei Grynyuk, Piano

Sunday, March 26, 2017, 3pm Zellerbach Hall National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine Theodore Kuchar, conductor Alexei Grynyuk, piano PROGRAM Giuseppe VERDI (1813 –1901) Overture to La forza del destino Sergei PROKOFIEV (1891 –1953) Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 26 Andante – Allegro Tema con variazioni Allegro, ma non troppo INTERMISSION Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH (1906 –1975) Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47 Moderato – Allegro non troppo Allegretto Largo Allegro non troppo THE ORcHESTRA National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine Volodymyr Sirenko, artistic director & chief conductor Theodore Kuchar, conductor laureate First Violins cellos Bassoons Markiyan Hudziy, leader Olena Ikaieva, principal Taras Osadchyi, principal Gennadiy Pavlov, sub-leader Liliia Demberg Oleksiy Yemelyanov Olena Pushkarska Sergii Vakulenko Roman Chornogor Svyatoslava Semchuk Tetiana Miastkovska Mykhaylo Zanko Bogdan Krysa Tamara Semeshko Anastasiya Filippochkina Mykola Dorosh Horns Roman Poltavets Ihor Yarmus Valentyn Marukhno, principal Oksana Kot Ievgen Skrypka Andriy Shkil Olena Poltavets Tetyana Dondakova Kostiantyn Sokol Valery Kuzik Kostiantyn Povod Anton Tkachenko Tetyana Pavlova Boris Rudniev Viktoriia Trach Basses Iuliia Shevchenko Svetlana Markiv Volodymyr Grechukh, principal Iurii Stopin Oleksandr Neshchadym Trumpets Viktor Andriiichenko Oleksandra Chaikina Viktor Davydenko, principal Oleksii Sechen Yuri і Kornilov Harps Grygorii Кozdoba Second Violins Nataliia Izmailova, principal Dmytro Kovalchuk Galyna Gornostai, principal Diana Korchynska Valentyna -

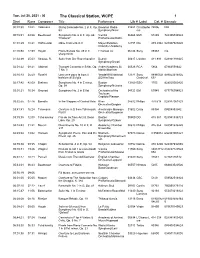

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jul 20, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 13:01 Volkmann String Serenade No. 2 in F, Op. Bavarian Radio 01487 Christopho 74506 N/A 63 Symphony/Nicol rus 00:15:3144:28 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 Vienna 06364 EMI 57445 724355744524 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Rattle 01:01:29 18:21 Hoffmeister Oboe Concerto in C Mayer/Potsdam 12355 DG 479 2942 028947929420 Chamber Academy 01:20:5012:59 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 49 in C Emanuel Ax 06244 Sony 89363 n/a sharp minor 01:34:49 25:03 Strauss, R. Suite from Der Rosenkavalier Detroit 00617 London 411 893 028941189325 Symphony/Dorati 02:01:2208:21 Albinoni Trumpet Concerto in B flat, Op. Andre/Academy St. 00526 RCA 5864 07863558642 7 No. 3 Martin/Marriner 02:10:43 05:59 Rossini Una voce poco fa from Il Yende/RAI National 12979 Sony 88985321 889853216925 barbiere di Siviglia SO/Armiliato Classical 692 02:17:4242:09 Brahms Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Boston 13169 BSO 1703 828020003425 Op. 98 Symphony/Nelsons 03:01:21 30:34 Gounod Symphony No. 2 in E flat Orchestra of the 04723 EMI 63949 077776394923 Toulouse Capitole/Plasson 03:32:5507:46 Borodin In the Steppes of Central Asia Kirov 08532 Philips 470 618 028947061823 Orchestra/Gergiev 03:41:4116:24 Telemann Overture in D from Tafelmusik, Amsterdam Baroque 01602 Erato 85394 08908853942 Part II Orchestra/Koopman 03:59:3512:08 Tchaikovsky Pas de six from Act III, Swan Boston 00500 DG 415 367 028941536723 Lake, Op. -

Josef Suk's Asrael Re-Envisioned Via Schoenberg

A STUDY IN CLARITY: JOSEF SUK’S ASRAEL RE-ENVISIONED VIA SCHOENBERG Volume I of II IVAN ARION KARST School of Arts and Media College of Arts and Social Sciences University of Salford, Salford, UK Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, October 2020 i Contents Table of Figures ........................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements..................................................................................................................... 7 Abstract: ‘A Study in Clarity: Suk Re-envisioned via Schoenberg’ ................................................. 8 Chapter 1: Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 Thesis Methodology ................................................................................................................. 1 A Study in Clarity: Literature Review ......................................................................................... 4 Chapter 2: Historical Context .................................................................................................... 10 Schoenberg: Transcription and the Verein .............................................................................. 10 Chapter 3: Analysis.................................................................................................................... 12 Transcription Techniques of the Verein ................................................................................. -

A B C a B C D a B C D A

24 go symphonyorchestra chica symphony centerpresent BALL SYMPHONY anne-sophie mutter muti riccardo orchestra symphony chicago 22 september friday, highlight season tchaikovsky mozart 7:00 6:00 Mozart’s fiery undisputed queen ofviolin-playing” ( and Tchaikovsky’s in beloved masterpieces, including Rossini’s followed by Riccardo Muti leading the Chicago SymphonyOrchestra season. Enjoy afestive opento the preconcert 2017/18 reception, proudly presents aprestigious gala evening ofmusic and celebration The Board Women’s ofthe Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Gala package guests will enjoy postconcert dinner and dancing. rossini Suite from Suite 5 No. Concerto Violin to Overture C P s oncert reconcert Reception Turkish The Sleeping Beauty Concerto. The SleepingBeauty William Tell conducto The Times . Anne-Sophie Mutter, “the (Turkish) William Tell , London), performs London), , media sponsor: r violin Overture 10 Concerts 10 Concerts A B C A B 5 Concerts 5 Concerts D E F G H I 8 Concerts 5 Concerts E F G H 5 Concerts 6 Conc. 5 Concerts THU FRI FRI SAT SAT SUN TUE 8:00 1:30 8:00 2017/18 8:00 8:00 3:00 7:30 ABCABCD ABCDAAB Riccardo Muti conductor penderecki The Awakening of Jacob 9/23 9/26 Anne-Sophie Mutter violin tchaikovsky Violin Concerto schumann Symphony No. 2 C A 9/28 9/29 Riccardo Muti conductor rossini Overture to William Tell 10/1 ogonek New Work world premiere, cso commission A • F A bruckner Symphony No. 4 (Romantic) A Alain Altinoglu conductor prokoFIEV Suite from The Love for Three Oranges Sandrine Piau soprano poulenc Gloria Michael Schade tenor gounod Saint Cecilia Mass 10/5 10/6 Andrew Foster-Williams 10/7 C • E B bass-baritone B • G Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe chorus director 10/26 10/27 James Gaffigan conductor bernstein Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront James Ehnes violin barber Violin Concerto B • I A rachmaninov Symphonic Dances Sir András Schiff conductor mozart Serenade for Winds in C Minor 11/2 11/3 and piano bartók Divertimento for String Orchestra 11/4 11/5 A • G C bach Keyboard Concerto No. -

Johannes Muller Stosch,Conductor

BOB COLE CONSERVATORY SYMPHONY JOHANNES MULLER STOSCH, CONDUCTOR WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2019 8:00PM CARPENTER PERFORMING ARTS CENTER PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. PROGRAM Scherzo Fantastique, Op. 25 ........................................................................................................................................ Josef Suk (1874-1935) Symphony No. 104 in D Major, “London” .................................................................................................Franz Josef Haydn Adagio - Allegro (1732-1809) Andante Menuetto and Trio Finale: Spiritoso INTERMISSION* La Noche de los Mayas (The Night of the Mayas) Suite ........................................................................Silvestre Revueltas 1. Noche de los Mayas (Night of the Mayas) (1899-1940) 2. Noche de jaranas (Night of Merrymakers) arr. José Limantour 3. Noche de Yucatán (Night of Yucatán) 4. Noche de encantamiento (Night of Enchantment) * You may text: (562)-774-2226 or email: [email protected] to ask question about the orchestra or today’s program during intermission. A few of the incoming questions will be addressed at the second half of the program. PROGRAM NOTES (Please hold applause until after the final movement of each piece.) Scherzo Fantastique, Op. 25 The Scherzo was composed in 1903 and premiered two years later in Prague. The end of the nineteenth century brought many now-distinct composers such as Gustav Mahler, Claude Debussy, and Antonin Dvořák to the forefront. Not only did these composers find great success in their compositions, but also in their various other jobs. For example, Mahler was a famed conductor before he was known as a composer, and Debussy was known for his teachings at the end of his life at the Paris Conservatory. Dvořák followed another path, one which took him to the United States as a professor of music during the years 1892-1895. -

A Survey of Czech Piano Cycles: from Nationalism to Modernism (1877-1930)

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: A SURVEY OF CZECH PIANO CYCLES: FROM NATIONALISM TO MODERNISM (1877-1930) Florence Ahn, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Larissa Dedova Piano Department The piano music of the Bohemian lands from the Romantic era to post World War I has been largely neglected by pianists and is not frequently heard in public performances. However, given an opportunity, one gains insight into the unique sound of the Czech piano repertoire and its contributions to the Western tradition of piano music. Nationalist Czech composers were inspired by the Bohemian landscape, folklore and historical events, and brought their sentiments to life in their symphonies, operas and chamber works, but little is known about the history of Czech piano literature. The purpose of this project is to demonstrate the unique sentimentality, sensuality and expression in the piano literature of Czech composers whose style can be traced from the solo piano cycles of Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884), Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904), Leoš Janáček (1854-1928), Josef Suk (1874-1935), Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1935) to Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942). A SURVEY OF CZECH PIANO CYCLES: FROM ROMANTICISM TO MODERNISM (1877-1930) by Florence Ahn Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2018 Advisory Committee: Professor Larissa Dedova, Chair Professor Bradford Gowen Professor Donald Manildi Professor