IGOR STRAVINSKY IGOR STRAVINSKY from "Great Lives: a Century in Obituaries"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artistic Hybridism in Stravinsky's Renard

Russia ‘Reimagined’: Artistic Hybridism in Stravinsky’s Renard (1915 -1916) © 2005 by Helen Kin Hoi Wong In his Souvenir sur Igor Stravinsky , the Swiss novelist Ramuz recalled his first impression of Stravinsky as a Russian man of possessiveness: What I recognized in you was an appetite and feeling for life, a love of all that is living.. The objects that made you act or react were the most commonplace... While others registered doubt or self-distrust, you immediately burst into joy, and this reaction was followed at once by a kind of act of possession, which made itself visible on your face by the appearance of two rather wicked-looking lines at the corner of your mouth. What you love is yours, and what you love ought to be yours. You throw yourself on your prey - you are in fact a man of prey. 1 Ramuz’s comment perhaps explains what make Stravinsky’s musical style so pluralistic - his desire to exploit native materials and adopt foreign things as if his own. When Stravinsky began working on the Russian libretto of Renard in 1915, he was living in Switzerland in exile, leaving France where he had established his career. As a Russian avant-garde composer of extreme folklorism (as demonstrated in the Firebird , Petrushka and the Rite ), Stravinsky was never on edge in France. His growing friendship with famous French artists such as Vati, Debussy, Ravel, Satie, Cocteau and Claudel indicated that he was gradually being perceived as part of the French artistic culture. In fact, this change of perception on Stravinsky was more than socially driven, as his musical language by the end of the War (1918) had clearly transformed to a new type which adhered to the French popular taste (as manifested in L'Histoire du Soldat , Five Easy Pieces and Ragtime ). -

Stravinsky, the Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance,"

/N81 AI2319 Ti VILSKY' USE OF IEhPIAN IN HIS ORCHESTRAL WORKS THE IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of M1- JiROF JU.SIC by Wayne Griffith, B. Mus. Conway, Arkansas January, 1955 TABLE OF CONTENT4 Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ,.. , , * . Chap ter I. THE USE OF PIANO1E A' Al ORCTHE TL I:ThUERIMT BEFOR 1910 . , , . , , l STRAICY II. S U6 OF 2E PIANO S E114ORCHES L ORK HIS OF "RUSIA PERIOD . 15 The Fire-Bird Pe~trouchka Le han u hossignol III. STAVIL C ' 0 USE OF TE PI 40IN 9M ORCHESTRAL .RKS OF HIS "NEO-CLASSIO" PERIOD . 56 Symphonyof Psalms Scherzo a la Russe Scenes IBfallet Symphony~in Three Movements BIIORPHYy * - . 100 iii 1I3T OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Berlioz, Leio, Finale, (from Berlioz' Treatise on Instrumentation, p . 157) . 4 2. Saint-Saena, ym phony in 0-minor, (from Prof. H. Kling's Modern Orchestration and Instrumentation, a a.~~~~*f0" 0. 7 p. 74) . 0 0 * * * 3. Moussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation Scene,'" 36-40 mm.f . -a - - --. " " . 10 4. oussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation :scene," mm. 241-247 . f . * . 11 5. imsky-Korsakoff, Sadko , (from rimkir -Korsakoff' s Principles of 0rchtiration, Lart II, p. 135) . 12 6. ximsky-Korsakoff, The Snow aiden, (from Zimsky torsatoff'c tTTrin~lecs ofhOrchestration, Part II, . 01) . - - . - . * - - . 12 7 . i s akosy-. o Rf, TVe <now %aiN , (f 0r 1;i s^ky Korsaoif ' s Prciniles of Orchestration, Part II, 'p. 58) . aa. .a. .a- -.-"- -a-a -r . .". 13 8. Stravinsky, The Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance," 9. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 94, 1974-1975

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Founded in 1881 by HENRY LEE HIGGINSON SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS Principal Guest Conductor NINETY- FOURTH SEASON 1974-1975 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President PHILIP K.ALLEN SIDNEY STONEMAN JOHN L. THORNDIKE Vice-President Vice-President Treasurer VERNON R. ALDEN ARCHIE C. EPPS III JOHN T. NOONAN ALLEN G. BARRY MRS HARRIS FAHNESTOCK MRS JAMES H. PERKINS MRS JOHN M. BRADLEY HAROLD D. HODGKINSON IRVING W. RABB RICHARD P. CHAPMAN E.MORTON JENNINGS JR PAULC. REARDON ABRAM T. COLLIER EDWARD M. KENNEDY MRS GEORGE LEE SARGENT NELSON J. DARLING JR EDWARD G. MURRAY JOHN HOYT STOOKEY TRUSTEES EMERITUS FRANCIS W. HATCH PALFREY PERKINS HENRY A. LAUGHLIN ADMINISTRATION OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THOMAS D. PERRY JR THOMAS W. MORRIS Executive Director Manager PAUL BRONSTEIN JOHN H. CURTIS MARY H. SMITH Business Manager Public Relations Director Assistant to the Manager FORRESTER C. SMITH DANIEL R. GUSTIN RICHARD C. WHITE Development Director Administrator of Assistant to Educational Affairs the Manager DONALD W. MACKENZIE JAMES F. KILEY Operations Manager, Operations Manager, Symphony Hall Tanglewood ELEANOR R. JONES Program Editor Copyright © 1974 by Boston Symphony Orchestra Inc. December SYMPHONY HALL BOSTON MASSACHUSETTS J 6 e 2 2 Meet Him In a Cloud of Chiffon Li Surely, he'll appreciate this graceful flow of gray / chiffon. Sc'oop necked and softly tiered skirted. • Ready to rise to an occasion. From our outstanding /Collection of long and short evening looks, ay or navy polyester chiffon. Misses sizes. $100 isses Dresses, in Boston and in Chestnut Hill Boston, Chestnut Hill, South \Shore, Northshore, Burlington, Wellesley BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS Principal Guest Conductor NINETY-FOURTH SEASON 1974-1975 THE BOARD OF OVERSEERS OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. -

Ballet? Y First the Ballerina Glides Across the Stage, Her Arms M Making Lovely Lines in the Air

My First alle B Album t What is Ballet? Firs The ballerina glides across the stage, her arms My t making lovely lines in the air. A beautiful tune comes from the strings of the large orchestra. She is the Sleeping Beauty: she was put into a allet deep magic sleep by the wicked witch. But she B lbum has now been woken by her handsome prince, A and he dances joyfully with her, athletic and strong. Another time, she is Princess Odette from Swan Lake, and around her the other dancers – swans in white chiffon – weave patterns in time to the music. And yet another time, she is the Sugar Plum Fairy celebrating the joy of Christmas in The Nutcracker. This is ballet, the classical dance that, once seen, is never forgotten. Even though today we have film and video games, ballet is still a powerful vision of beauty and excitement. The dancers use the strength of an athlete, the balance of a gymnast and the sensitivity of a violinist to tell stories through their dancing. Here is some of the best music which has propelled dancers for hundreds of years. 2 Tchaikovsky Swan Lake Stravinsky The Firebird 1 Scene 2:37 3 Scene I. The Firebird’s Dance 1:19 Keyword: Oboe Keyword: Fire Swan Lake is a ballet from Russia about a prince called Siegfried. In the forest he finds A firebird is a brightly coloured magical bird that comes a mysterious lake where swans are swimming, led by a beautiful but sad swan wearing out of the fire. -

Elements of Traditional Folk Music and Serialism in the Piano Music of Cornel Țăranu

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music Music, School of 12-2013 ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU Cristina Vlad University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Commons Vlad, Cristina, "ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU" (2013). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 65. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU by Cristina Ana Vlad A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Mark Clinton Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2013 ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU Cristina Ana Vlad, DMA University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Mark Clinton The socio-political environment in the aftermath of World War II has greatly influenced Romanian music. During the Communist era, the government imposed regulations on musical composition dictating that music should be accessible to all members of society. -

Igor Strav Thursday 21 & Sunday 24 September

Thursday 21 & Sunday 24 September Igor Stravinsky in Profile 1882–1971 / profile by Paul Griffiths LSO SEASON CONCERT hird in a family of four sons, Before that was completed, a ballet based In 1939, soon after the deaths of his wife STRAVINSKY INTRODUCTION from Paul Griffiths he had a comfortable upbringing in on 18th-century music, Pulcinella (1919–20), and mother, he sailed to New York with St Petersburg, where his father opened the door to a whole neoclassical period, Vera, whom he married, and with whom he Stravinsky The Firebird (original ballet) Writing back to a Russian friend in 1912, was a Principal Bass at the Mariinsky Theatre. which was to last three decades and more. settled in Los Angeles. Following his opera Interval – 20 minutes as he worked in Switzerland on The Rite In 1902 he started lessons with Rimsky- He also began spending much of his time The Rake’s Progress (1947–51) he began to Stravinsky Petrushka (1947 version) of Spring, Stravinsky remarked: ‘It is as Korsakov, but he was a slow developer, in Paris and on tour with his mistress Vera interest himself in Schoenberg and Webern, Interval – 20 minutes if twenty and not two years had passed and hardly a safe bet when Diaghilev Sudeikina, while his wife, mother and children and within three years had worked out a Stravinsky The Rite of Spring since The Firebird was composed’. commissioned The Firebird. The success lived elsewhere in France. Up to the end of new serial style. Sacred works became more STRA This evening we have the rare opportunity of that work encouraged him to remain the 1920s, his big works were nearly all for and more important, to end with Requiem Sir Simon Rattle conductor to relive those packed and extraordinary in western Europe, writing scores almost the theatre (including the nine he wrote for Canticles (1965–66), which was performed two years in two hours, following the annually for Diaghilev. -

Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba

COMPARISON AND CONTRAST OF PERFORMANCE PRACTICE OF THE TUBA IN IGOR STRAVINSKY’S THE RITE OF SPRING, DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN D MAJOR, OP. 47, AND SERGEI PROKOFIEV’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN B FLAT MAJOR, OP. 100 Roy L. Couch, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2006 APPROVED: Donald C. Little, Major Professor Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Minor Professor Keith Johnson, Committee Member Brian Bowman, Coordinator of Brass Instrument Studies Graham Phipps, Program Coordinator of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Couch, Roy L., Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba in Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 in D major, Op. 47, and Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, Op. 100, Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2006, 46 pp.,references, 63 titles. Performance practice is a term familiar to serious musicians. For the performer, this means assimilating and applying all the education and training that has been pursued in a course of study. Performance practice entails many aspects such as development of the craft of performing on the instrument, comprehensive knowledge of pertinent literature, score study and listening to recordings, study of instruments of the period, notation and articulation practices of the time, and issues of tempo and dynamics. The orchestral literature of Eastern Europe, especially Germany and Russia, from the mid-nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century provides some of the most significant and musically challenging parts for the tuba. -

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky Source: http://www.8notes.com/biographies/stravinsky.asp ‘Even during his lifetime, Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was a legendary figure. His once revolutionary work were modern classics, and he influenced three generations of composers and other artists. Cultural giants like Picasso and T. S. Eliot were his friends. President John F. Kennedy honored him at a White House dinner in his eightieth year. 'Stavinsky was born in Oranienbaum, Russia, near St. Petersburg (Leningrad), grew up in a musical atmosphere, and studied with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. He had his first important opportunity in 1909, when the impresario Sergei Diaghilev heard his music. Diaghilev was the director of the Russian Ballet, an extremely influential troupe which employed great painters as well as important dances, choreographers, and composers. Diaghilev first asked Stravinsky to orchestrate some piano pieces by Chopin as ballet music and then, in 1910, commissioned an original ballet, The Firebird, which was immensely successful. A year later (1911), Stravinsky's second ballet, Petrushka, was performed, and Stravinsky was hailed as a modern master. When his third ballet, The Rite of Spring (a savage, brutal portrayal of a prehistoric ritual in which a young girl is sacrificed to the god of Spring.), had its premiere in Paris in 1913, a riot erupted in the audience--spectators were shocked and outraged by its pagan primitivism, harsh dissonance, percussiveness, and pounding rhythms--but it too was recognized as a masterpiece and influenced composers all over the world. 'During World War I, Stravinsky sought refuge in Switzerland; after the armistice, he moved to France, his home until the onset of World War II, when he came to the United States. -

The Sleeping Beauty Untouchable Swan Lake In

THE ROYAL BALLET Director KEVIN O’HARE CBE Founder DAME NINETTE DE VALOIS OM CH DBE Founder Choreographer SIR FREDERICK ASHTON OM CH CBE Founder Music Director CONSTANT LAMBERT Prima Ballerina Assoluta DAME MARGOT FONTEYN DBE THE ROYAL BALLET: BACK ON STAGE Conductor JONATHAN LO ELITE SYNCOPATIONS Piano Conductor ROBERT CLARK ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE Concert Master VASKO VASSILEV Introduced by ANITA RANI FRIDAY 9 OCTOBER 2020 This performance is dedicated to the late Ian Taylor, former Chair of the Board of Trustees, in grateful recognition of his exceptional service and philanthropy. Generous philanthropic support from AUD JEBSEN THE SLEEPING BEAUTY OVERTURE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE UNTOUCHABLE EXCERPT Choreography HOFESH SHECHTER Music HOFESH SHECHTER and NELL CATCHPOLE Dancers LUCA ACRI, MICA BRADBURY, ANNETTE BUVOLI, HARRY CHURCHES, ASHLEY DEAN, LEO DIXON, TÉO DUBREUIL, BENJAMIN ELLA, ISABELLA GASPARINI, HANNAH GRENNELL, JAMES HAY, JOSHUA JUNKER, PAUL KAY, ISABEL LUBACH, KRISTEN MCNALLY, AIDEN O’BRIEN, ROMANY PAJDAK, CALVIN RICHARDSON, FRANCISCO SERRANO and DAVID YUDES SWAN LAKE ACT II PAS DE DEUX Choreography LEV IVANOV Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY Costume designer JOHN MACFARLANE ODETTE AKANE TAKADA PRINCE SIEGFRIED FEDERICO BONELLI IN OUR WISHES Choreography CATHY MARSTON Music SERGEY RACHMANINOFF Costume designer ROKSANDA Dancers FUMI KANEKO and REECE CLARKE Solo piano KATE SHIPWAY JEWELS ‘DIAMONDS’ PAS DE DEUX Choreography GEORGE BALANCHINE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY -

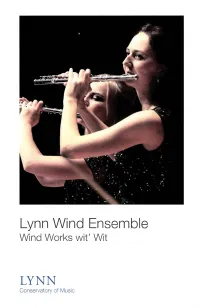

2015-2016 Lynn University Wind Ensemble-Wind Works Wit'wit

Lynn Wind Ensemble Wind Works wit' Wit LYNN Conservatory of Music Wind Ensemble Roster FLUTE T' anna Tercero Jared Harrison Hugo Valverde Villalobos Scott Kemsley Robert Williams Al la Sorokoletova TRUMPET OBOE Zachary Brown Paul Chinen Kevin Karabell Walker Harnden Mark Poljak Trevor Mansell Alexander Ramazanov John Weisberg Luke Schwalbach Natalie Smith CLARINET Tsukasa Cherkaoui TROMBONE Jacqueline Gillette Mariana Cisneros Cameron Hewes Halgrimur Hauksson Christine Pascual-Fernandez Zongxi Li Shaquille Southwell Em ily Nichols Isabel Thompson Amalie Wyrick-Flax EUPHONIUM Brian Logan BASSOON Ryan Ruark Sebastian Castellanos Michael Pittman TUBA Sodienye Fi nebone ALTO SAX Joseph Guimaraes Matthew Amedio Dannel Espinoza PERCUSSION Isaac Fernandez Hernandez TENOR SAX Tyler Flynt Kyle Mechmet Juanmanuel Lopez Bernadette Manalo BARITONE SAX Michael Sawzin DOUBLE BASS August Berger FRENCH HORN Mileidy Gonzalez PIANO Shaun Murray Al fonso Hernandez Please silence or turn off all electronic devices, including cell phones, beepers, and watch alarms. Unauthorized recording or photography is strictly prohibited Lynn Wind Ensemble Kenneth Amis, music director and conductor 7:30 pm, Friday, January 15, 2016 Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Onze Variations sur un theme de Haydn Jean Fran c;; aix lntroduzione - Thema (1912-1997) Variation 1: Pochissimo piu vivo Variation 2: Moderato Variation 3: Allegro Variation 4: Adagio Variation 5: Mouvement de va/se viennoise Variation 6: Andante Variation 7: Vivace Variation 8: Mouvement de valse Variation 9: Moderato Variation 10: Mo/to tranquil/a Variation 11 : Allegro giocoso Circus Polka Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Hommage a Stravinsky Ole Schmidt I. (1928-2010) II. Ill. Spiel, Op.39 Ernst Toch /. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE CANADIAN MUSIC SINCE 1940: a QUESTION of NATIONALISM a Thesis Submitted in Partial Satis

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE CANADIAN MUSIC SINCE 1940: A QUESTION OF NATIONALISM A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music by Ronald Frederick Erin August, 1983 J:lhe Thesis of Ronald Frederick Erin is approved: California StD. te Universi tJr, Northridge ii PREFACE This thesis represents a survey of Canadian music since 1940 within the conceptual framework of 'nationalism'. By this selec- tive approach, it does not represent a conclusive view of Canadian music nor does this paper wish to ascribe national priorities more importance than is due. However, Canada has a unique relationship to the question of nationalism. All the arts, including music, have shared in the convolutions of national identity. The rela- tionship between music and nationalism takes on great significance in a country that has claimed cultural independence only in the last 40 years. Therefore, witnessed by Canadian critical res- ponse, the question of national identity in music has become an important factor. \ In utilizing a national focus, I have attempted to give a progressive, accumulative direction to the six chapters covered in this discussion. At the same time, I have attempted to make each chapter self-contained, in order to increase the paper's effective- ness as a reference tool. If the reader wishes to refer back to information on the CBC's CRI-SM record label or the Canadian League of Composers, this informati6n will be found in Chapter IV. Simi- larly, work employing Indian texts will be found in Chapter V. Therefore, a certain amount of redundancy is unavoidable when interconnecting various components. -

David Justin CV 2014 Pennsylvania Ballet

David Justin 4603 Charles Ave Austin TX 787846 Tel: 512-576-2609 Email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.davidjustin.net CURRICULUM VITAE ACADEMIC EDUCATION • University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, Master of Arts in Dance in Education and the Community, May 2000. Thesis: Exploring the collaboration of imagination, creativity, technique and people across art forms, Advisor: Tansin Benn • Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, Edward Kemp, Artistic Director, London, United Kingdom, 2003. Certificate, 285 hours training, ‘Acting Shakespeare.’ • International Dance Course for Professional Choreographers and Composers, Robert Cohen, Director, Bretton College, United Kingdom, 1996, full scholarship DANCE EDUCATION • School of American Ballet, 1987, full scholarship • San Francisco Ballet School, 1986, full scholarship • Ballet West Summer Program, 1985, full scholarship • Dallas Metropolitan Ballet School, 1975 – 1985, full scholarship PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Choreographer, 1991 to present See full list of choreographic works beginning on page 6. Artistic Director, American Repertory Ensemble, Founder and Artistic Director, 2005 to present $125,000 annual budget, 21 contract employees, 9 board members11 principal dancers from the major companies in the US, 7 chamber musicians, 16 performances a year. McCullough Theater, Austin, TX; Florence Gould Hall, New York, NY; Demarco Roxy Art House, Edinburgh, Scotland; Montenegrin National Theatre, Podgorica, Montenegro; Miller Outdoor Theatre, Houston, TX, Long Center for the Performing Arts,