How Grimaldi Group Survived the Downturn Family-Run Shipowner Managed to Stay in the Black Last Year, Thanks in Part to Its Stra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cs Moby-Tirrenia-Toremar Raddoppio

______________________________ MOBY, RADDOPPIANO LE CORSE PER LA SARDEGNA DA LIVORNO PRENOTAZIONI PIU’ 80% PER MOBY, TIRRENIA E TOREMAR Milano, 10 giugno 2021 – Moby, Tirrenia e Toremar si confermano sempre più i vettori ufficiali dell’estate della ripartenza. Le tre Compagnie, che sono la maggiore infrastruttura sul mare del Paese, stanno registrando l’80% in più di prenotazioni. E il trend di coloro che vogliono raggiungere le mete servite – Sardegna, Sicilia, Corsica, Isola d’Elba, Arcipelago Toscano, collegate con Genova, Livorno, Piombino, Civitavecchia e Napoli – è ulteriormente in crescita. Da oggi arriva un’altra notizia attesissima dai viaggiatori: le corse fra Livorno e Olbia, in entrambe le direzioni, raddoppiano con quattro partenze al giorno, diurne e notturne, con anche un’ulteriore opportunità appositamente studiata per i viaggiatori: le corse diurne da Livorno partono alle 9.00, quelle da Olbia alle 11.00, per permettere ai turisti di godersi la vacanza fino all’ultimo raggio di sole e di arrivare nel porto dell’Isola Bianca in tutta tranquillità. Moby e Tirrenia sono sempre più il ponte fra la Sardegna e il resto dell’Italia, d’estate e d’inverno, tanto da aver già aperto le prenotazioni fino a maggio 2022 sulla Genova-Porto Torres e sulla Civitavecchia-Olbia, senza alcuna sovvenzione pubblica. Ancora una volta Moby, Tirrenia e Toremar si confermano la prima infrastruttura italiana sul mare, con più comodità, più corse, più mete, più comfort a bordo e anche assoluta sicurezza sanitaria: il care manager, un ufficiale dedicato al controllo delle misure anti-Covid, appositi zainetti sanificatori di cabine e spazi comuni e possibilità di mangiare anche in cabina con il room service. -

Strategie Trasporto Marittimo

STRATEGIE TRASPORTO MARITTIMO faremo di questa società di navigazione Grimaldi di Grimaldi Lines. A scatenare concorrenza. Fuori della cordata Cin, la più forte Compagnia nazionale e in- da subito malumori e proteste, anche dei rimane solo Corsica Ferries», incalza, ternazionale delle Autostrade del mare». camionisti, è stato il raddoppio estivo invece, Cinzia Franchini. Nel frattempo, la regione Sardegna sta del costo del ticket da e per la Sardegna Eppure, la privatizzazione della Tirre- allestendo una sua flotta che sfiderà pro- praticato sui traghetti di Moby, Snav, nia era stata salutata con un sospiro di prio le navi dell’ex “Alitalia dei mari”, un Grandi navi veloci e Sardinia Ferries. Le sollievo. Il 25 luglio scorso, infatti, dopo baraccone che al momento della cessio- prime tre compagnie appartengono agli 70 anni, si è chiuso un capitolo oneroso Battaglia ne era riuscito ad accumulare un debito armatori che hanno acquisito Tirrenia. per le casse dello Stato: solo dal 2001 al Con l’acquisto di Tirrenia di 550 milioni, nonostante gli annuali «Non avevamo un’alternativa per po- 2007, la Compagnia pubblica era costata contributi statali. ter far fronte all’aumento del carburante, un miliardo e mezzo di euro. A guidarla da parte dei tre più grandi Molta la carne al fuoco, dunque. An- che all’improvviso è schizzato alle stelle», era stato, fino al 2010, Francesco Pigo- che dopo la cessione, per 380 milioni, si difendono alla Cin. rini, rimasto in carica per 18 anni e che armatori italiani, si rischia della flotta pubblica alla Compagnia «La paura dei camionisti è che si sia fino alla fine ha tentato di opporsi alla La compagnia di italiana di navigazione (Cin) che ha co- passati dal baraccone pubblico al mo- vendita. -

Of the EC Treaty Regarding the Tariffs for Piloting in the Port of Genoa (Only the Italian Text Is Authentic) (Text with EEA Relevance)

5 . ii . 97 Ien Official Journal of the European Communities L 301 /27 COMMISSION DECISION of 21 October 1997 relating to a proceeding pursuant to Article 90 (3) of the EC Treaty regarding the tariffs for piloting in the Port of Genoa (Only the Italian text is authentic) (Text with EEA relevance) (97/745/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, ferent tariffs to maritime transport undertakings, depending on whether they operate transport Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European services between Member States or between ports Community, and in particular Article 90 (3) thereof, situated on national territory, in so far as trade between Member States is affected'. Having regard to the complaint lodged by Tourship on 21 June 1994 concerning the system of reductions in On 26 May 1994, Tourship (formerly Corsica piloting tariffs in the port of Genoa, withdrawn on 8 July Ferries) applied to the Corporation of Pilots of the 1997, Port of Genoa for the reductions granted to vessels engaged in cabotage, pursuant to the abovemen Having given the Italian authorities, the Corpo dei Piloti tioned judgment. On 1 June 1994, the Corporation del Porto di Genova (Corporation of Pilots of the Port of informed Tourship that it was obliged to apply the Genoa), Tirrenia, Viamare di Navigazione, Navarma tariffs laid down by the Ministry for the Merchant and Tourship the opportunity to make known their views Navy. The Ministry not having issued new tariffs at on the objections raised by the Commission concerning that time , the Corporation had been compelled to the system of reductions in piloting tarifs in the port of apply the tariffs objected to by the Court . -

Décision (Ue) 2020/1412 De La Commission

12.10.2020 FR Jour nal officiel de l’Union européenne L 332/45 DÉCISION (UE) 2020/1412 DE LA COMMISSION du 2 mars 2020 concernant les mesures d’aide SA.32014, SA.32015, SA.32016 (11/C) (ex 11/NN) mises à exécution par l’Italie en faveur de Tirrenia di Navigazione et de son acquéreur Compagnia Italiana di Navigazione [notifiée sous le numéro C(2020) 1110] (Le texte en langue italienne est le seul faisant foi.) (Texte présentant de l’intérêt pour l’EEE) LA COMMISSION EUROPÉENNE, vu le traité sur le fonctionnement de l’Union européenne, et notamment son article 108, paragraphe 2, premier alinéa, vu l’accord sur l’Espace économique européen, et notamment son article 62, paragraphe 1, point a), après avoir invité les parties intéressées à présenter leurs observations conformément auxdits articles (1) et vu ces observations, considérant ce qui suit: 1. PROCÉDURE (1) Le 5 octobre 2011, la Commission a ouvert une procédure formelle d’examen à l’égard de plusieurs mesures adoptées par l’Italie en faveur des compagnies de l’ancien groupe Tirrenia (2) (ci-après la «décision de 2011»). L’enquête a porté, entre autres, sur les compensations accordées à Tirrenia di Navigazione (ci-après «Tirrenia») pour l’exploitation de nombreuses lignes maritimes à partir du 1er janvier 2009 et sur le processus de privatisation (voir section 2.3.3) qui a conduit à l’acquisition de la branche d’entreprise Tirrenia (voir aussi considérant 27) par Compagnia Italiana di Navigazione (ci-après «CIN»). (2) La décision de 2011 a été publiée au Journal officiel de l’Union européenne (3). -

Competition Law in Italy the First 20 Years of Law and Practice

Mario Siragusa – Matteo Beretta – Matteo Bay Competition Law in Italy The first 20 years of law and practice CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION A. General Comparison of Italy’s Competition Laws, Enforcement, Procedures with Those of the United States B. Overview of Applicable Statutes 1. Main Legislative Reforms (a) Interim Measures (b) Commitments (c) Leniency Program 2. Relationship between EU and National Competition Rules C. Overview of Structure, Independence and Jurisdiction of Enforcement Agencies D. Overview of Structure, Independence, and Jurisdiction of Judicial Authorities E. Additional Policy & Practical Considerations 1. Costs and Time Considerations in Litigation 2. Costs and Time Considerations in Administrative Proceedings 3. Intervention of Agencies and Political Bodies in Litigation II. OVERVIEW A. General Policies Underlying Italy’s Competition Laws 1. Consumer Welfare 2. Protection of Smaller Enterprises Against Larger Enterprises 3. Protection of Domestic Enterprises Against Foreign Competition B. Role of Economic Doctrines and Analysis 1. Generally 2. Use of Specific Economic Analysis 3. Extent to Which Courts Have Embraced Economic Analysis III. SUBSTANTIVE LAW A. Horizontal Agreements and Practices 1. General Principles (a) Introduction (b) The Notion of “Undertaking” (c) Agreements, Decisions, and Concerted Practices (d) Restrictive Object or Effect (e) Appreciability of the Restriction (f) The Burden of Proof (g) Reliability of Documentary Evidence (h) Relevance of Criminal Findings in the Context of the Competition Authority’s -

TARIFFE TRAGHETTI DA/PER LA SARDEGNA Provvedimento N

I743 - TARIFFE TRAGHETTI DA/PER LA SARDEGNA Provvedimento n. 24405 L’AUTORITÀ GARANTE DELLA CONCORRENZA E DEL MERCATO NELLA SUA ADUNANZA dell’11 giugno 2013; SENTITO il Relatore Professore Carla Bedogni Rabitti; VISTO l’articolo 101 del Trattato sul Funzionamento dell’Unione Europea; VISTO il D.P.R. 30 aprile 1998 n. 217; VISTO il Regolamento del Consiglio 16 dicembre 2002 n. 1/2003; VISTA la Comunicazione della Commissione sulla cooperazione nell’ambito della rete delle autorità garanti della concorrenza, del 27 aprile 2004; VISTA la delibera dell’11 maggio 2011, con la quale è stata avviata un’istruttoria, ai sensi dell’articolo 14 della legge n. 287/90, per presunta violazione dell’articolo 101 del TFUE, nei confronti delle società Onorato Partecipazioni S.r.l., Moby S.p.A., Marinvest S.r.l., Investitori Associati SGR S.p.A., Grandi Navi Veloci S.p.A., SNAV S.p.A., Lota Marittime S.A. e Forship S.p.A.; VISTA la delibera del 28 giugno 2011, con la quale il procedimento è stato esteso soggettivamente anche nei confronti delle società Clessidra SGR S.p.A. e L19 S.p.A.; VISTE le delibere adottate in data 17 ottobre 2012 e 13 marzo 2013 nelle quali il termine di chiusura del procedimento è stato prorogato rispettivamente al 28 marzo 2013 e al 19 giugno 2013; VISTA la Comunicazione delle Risultanze Istruttorie trasmessa alle parti in 21 marzo 2013; VISTA la propria comunicazione alla Commissione Europea, ai sensi dell’articolo 11, paragrafo 4, del Regolamento (CE) n. 1/2003; VISTI gli atti del procedimento e la documentazione acquisita nel corso dell’istruttoria; CONSIDERATO quanto segue: I. -

Grandi Navi Veloci (GNV) Grimaldi Lines SNAV Tirrenia

21.09.2020 Puoi usufruire di TIM in Nave sui seguenti traghetti: Grandi Navi Veloci (GNV) Excellent Excelsior Fantastic La Superba La Suprema Majestic Splendid Rhapsody GNV Atlas GNV Cristal GNV Azzurra GNV Allegra Grimaldi Lines Cruise Barcelona Cruise Roma Cruise Europa Cruise Olympia EuroFerry Egnazia EuroFerry Olympia Catania Zeus Palace Olbia Cruise Smeralda Bonaria Cruise Ausonia Corfu Florencia Venezia SNAV Adriatico Tirrenia Athara Bithia Florio Janas Nuraghes Rubattino Sharden TIM - Uso Interno - Tutti i diritti riservati. 21.09.2020 Moby Lines Moby Aki Moby Drea Moby Corse Moby Otta Moby Tommy Moby Vincent Moby Wonder Moby Zaza Moby Kiss Moby Ariadne Moby Niki Corsica Ferries Marina Seconda Sardinia Vera Mega Andrea Mega Express Mega Express II Sardinia Regina Mega Express V Mega Express IV Mega Express III Sardinia Smeralda Corsica Victoria Pascal Lota Superfast Superfast I Superfast II Superfast XI Finnlines Finnfellow Finnpartner Finnlady Finnmaid Finnswan Finnstar TIM - Uso Interno - Tutti i diritti riservati. 21.09.2020 Brittany Ferries Armorique Baie de Seine Barfleur Bretagne Cap Finistère Etretat Mont St-Michel Normandie Normandie Express Pont-Aven Unity Polonia Skania Corsica Linea Vizzavona A Nepita Ventouris Ferries Rigel I Rigel II Rigel III Bari Rigel VII Abou Mehri Orient Queen II Intership Olimpia TIM - Uso Interno - Tutti i diritti riservati. 21.09.2020 European Seaways Golden Bridge Polferries Cracovia Nova Star Oceanwide Expeditions Plancius Hondius Ortelius TIM - Uso Interno - Tutti i diritti riservati. . -

2016-Moby-Lines-Komp.Pdf

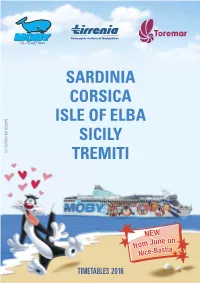

THE FRIENDLY SHIPS SARDINIA CORSICA ISLE OF ELBA 10/12/2015 SICILY EDITION ST 1 TREMITI TIMETABLES 2016 THE MOBY-FLEET MOBY AKI AND MOBY WONDER Category: Fast Cruise Ferry - Passengers: 2.200 - Vehicles: 750 FOR SARDINIA 175 meters long, 27 meters broad. Speed 29 knots. Air-conditioning, 320 cabins with private facilities, hair dryer and radio, junior suites for 4 persons, area equipped with coach seats, panoramic show lounge, 4 cafeterias, à la carte restaurant, self-service restaurant, pizzapoint, ice-cream parlor, snackbar, children’s play area, AND CORSICA pool, sundeck, sport bar, kennel for domestic pets, stabilizers. ISPS certification (International Ship and Port facility Security code). Assignment: Comfort Class and Green Star. Sides decorated with “Looney Tunes”. offers you since ever best service, and each day in each season a save crossing because you can count on the experience and a tradition of 130 years within the maritime transportation field. This certificates the Registro Navale Italiano (RINA) by the certification “Safety Manage- ment System”, an international award for quality, security and environment protection executed since 1994. In 2015, MOBY again received the MOBY TOMMY INSTALLATION OF NEW CABINS IN WINTER 2015 quality seal “No. 1 in gold”, a cer- Category: Fast Cruise Ferry - Passengers: 2.200 - Vehicles: 1.000 or 2.000 tification that in Italy is a confir- linear meters mation of guarantee about quality 212 meters long, 25 meters broad. Speed 30 knots. Cabins with private facilities, coach seats, à la carte restaurant, self-service restaurant, for the consumer and about success for the pizzapoint, ice-cream parlor, cafeteria, sport bar, admiral pub, children’s world with video games enterprise. -

Moby E Tirrenia, La Continuità Territoriale Tra Genova E Porto Torres: “Senza Sovvenzioni” Di Redazione 01 Giugno 2021 – 18:05

1 Moby e Tirrenia, la continuità territoriale tra Genova e Porto Torres: “Senza sovvenzioni” di Redazione 01 Giugno 2021 – 18:05 Liguria. Moby e Tirrenia si confermano una volta di più le migliori alleate della Sardegna, per tutto l’anno, e aprono già oggi le prenotazioni sulla Genova-Porto Torres e sulla Civitavecchia-Olbia fino a maggio 2022. Lo si legge in un comunicato stampa della compagnia. “Il nuovo piano industriale di Moby e di Tirrenia non prevede alcun tipo di sovvenzione, garantendo un perimetro di rotte pressoché inalterato rispetto a quello attuale, con un livello di servizio sempre ottimo e con tariffe in linea con quelle per la continuità territoriale anche senza la Convenzione con lo Stato italiano. Quindi, anche alla luce dell’esito del bando per la Genova-Porto Torres, Moby e Tirrenia credono che quella rotta non abbia bisogno di sostegno pubblico e lo dimostrano con i fatti. Quindi, per assicurare la continuità territoriale e certezza della mobilità per i sardi, oltre che per dare le necessarie rassicurazioni al territorio che il Gruppo ha l’onore di servire da 140 anni, per coloro che devono raggiungere l’Isola aprono già oggi le prenotazioni fino a maggio 2022, assicurando lo stesso livello di servizio richiesto dal bando e con le tariffe per i passeggeri in linea con quelle previste dallo stesso, proprio perché convinti che questa tratta possa essere esercitata senza necessità di sovvenzioni agli armatori. Ma, oltre alla Genova-Porto Torres, che quest’estate sarà ulteriormente rafforzata con corse diurne e notturne, Moby e Tirrenia assicurano anche ulteriori rotte senza alcuna sovvenzione: da dicembre è infatti esercitata la Genova-Olbia, una nuova linea dedicata alle merci, così come sempre per le merci parte la Napoli-Cagliari, anch’essa senza contributi pubblici, linea per la quale invece un altro operatore riceve la sovvenzione statale. -

“Traghetti E Crociere”

“TraGHETTI E CROCiere” EDIZIONE 2021 © RIPRODUZIONE RISERVATA Nicola Capuzzo - Direttore responsabile SHIPPING ITALY Edizione 2021 1 Indice I. Introduzione pag. 4 II. Giampieri (Assoporti): “Traghetti nel Tirreno avvantaggiati. Urge semplificazione” pag. 6 III. Cosa potersi aspettare dalla ripartenza del maritime tourism in Italia pag. 7 IV. Le crociere in Italia: i numeri della ripartenza dopo un anno di sofferenza pag. 8 IV. Le navi di Costa e Msc stanno tornando a mollare gli ormeggi: le date e i porti della ripresa pag. 9 VI. Come è cambiato il mercato dei traghetti in Italia negli ultimi 12 mesi pag. 11 VII. I traghetti chiedono di rimuovere il limite della capacità ridotto al 50% pag. 14 VIII. Traghetti in Italia: chi li costruisce e chi li ordina pag. 15 IX. Ecco il dettaglio di chi e quando riceverà gli 800 milioni del Pnrr per i traghetti pag. 17 X. Stretto di Messina: l’analisi dei trasporti marittimi e i prossimi investimenti di Rfi pag. 18 e BluJet sul naviglio XI. Moby: “Niente più cruise ferry, i traghetti del futuro per noi sono ro-pax flessibili” pag. 20 XII. Grimaldi: “In vista consolidamento, più trailer e un business passeggeri diverso” pag. 22 XIII. Navigazione Libera del Golfo: diversificazione in vista e una nuova ammiraglia in arrivo pag. 23 XIV. Caronte & Tourist: ampio rinnovo della flotta all’orizzonte pag. 24 XV. Bluferries si prepara ad accogliere la nuova nave Sikania pag. 25 XVI. Liberty lines: frequenza delle linee aumentata per sopperire alla limitazione pag. 26 della capacità passeggeri XVII. Grandi Navi Veloci: nuove navi e nuove line in Italia e in Spagna pag. -

HIKING in CINQUE TERRE Hiking in Cinque Terre Does Not Require a High Level of Fitness, However You Need to Be Prepared for a Full Day of Hiking, Mostly up and Down

SAN MARINO VIAGGI E VACANZE S.p.A. a socio unico Via III Settembre, 99 - 47891 Dogana - RSM (Repubblica di San Marino) - Tel 0549/971011 [email protected] - www.sanmarinoviaggivacanze.com Capitale Sociale € 200.000,00 i.v. - COE SM 02851 SAN MARINO VIAGGI E VACANZE S.p.A. a socio unico Via III Settembre, 99 - 47891 Dogana - RSM (Repubblica di San Marino) - Tel 0549/971011 [email protected] - www.sanmarinoviaggivacanze.com Capitale Sociale € 200.000,00 i.v. - COE SM 02851 LIGURIA SAN MARINO VIAGGI E VACANZE S.p.A. a socio unico Via III Settembre, 99 - 47891 Dogana - RSM (Repubblica di San Marino) - Tel 0549/971011 [email protected] - www.sanmarinoviaggivacanze.com Capitale Sociale € 200.000,00 i.v. - COE SM 02851 SAN MARINO VIAGGI E VACANZE S.p.A. a socio unico Via III Settembre, 99 - 47891 Dogana - RSM (Repubblica di San Marino) - Tel 0549/971011 [email protected] - www.sanmarinoviaggivacanze.com Capitale Sociale € 200.000,00 i.v. - COE SM 02851 Best time to visit Liguria depends on your preferences. If you like sea, It is worth visiting the Ligurian coast from mid May till mid September. On the other hand, if you like sightseeing and mountains and hiking, note that the season begins earlier – mid March till the middle of October. The wintertime, form November to February is characterized by cold weather and some amenity closures, but it can be very charming especially during the Christmas season. SAN MARINO VIAGGI E VACANZE S.p.A. a socio unico Via III Settembre, 99 - 47891 Dogana - RSM (Repubblica di San Marino) - Tel 0549/971011 [email protected] - www.sanmarinoviaggivacanze.com Capitale Sociale € 200.000,00 i.v. -

General Transport Conditions for Passengers and Carried Along Vehicles

GENERAL TRANSPORT CONDITIONS FOR PASSENGERS AND CARRIED ALONG VEHICLES CONTENT Preliminary remarks Art.1 Transport conditions Art.2 Validity of ticket Art.3 Accommodation Art.4 Ticket cancellation and refunds Art.4a Application of vouchers Art.5 Loss or theft of ticket Art.6 Non-receipt of online tickets Art.7 Rebooking charges Art.8 Malfunction of the vessel – cancellation of departure – change of route Art.9 Delays Art.10 Special fares – special conditions Art.11 Call centre Art.12 Fares, surcharges and other costs Art.13 Check-in Art.14 Embarkation and disembarkation of vehicles Art.15 Behaviour of passengers on board Art.16 Transport of pregnant women Art.17 Children and teenagers Art.18 Animals and protected species Art.19 Transport of weapons Art.20 Luggage – lost items Art.21 Passenger details Art.22 Health status of the passenger Art.23 Disabled persons and persons with limited mobility Art.24 Information on embarkation and rules for crossing Art.25 Safety information and ISPS costs Art.26 Complaints Art.27 Applicable law and place of jurisdiction Art.28 Responsibility of the executing transport company Art.29 License plate Art.30 Group tariffs Art.31 Cargo transport Art.32 Types of carried along vehicles Art.33 Supplements and amendments Art.34 Procurement clause Definition of terms for the following text: Company/Transport Company: Compagnia Italiana di Navigazione S.p.A. • Via Larga, 26 CAP 20122 MILANO (place of jurisdiction) • Piazzale dei Marmi 12 CAP 57123 Livorno (operative and administrative seat) Usually, the contractual Transport Company is the maritime transport company.