Collaboration and Firm Competitiveness Among Airlines in Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final AFI RVSM Approvals 05 June 08

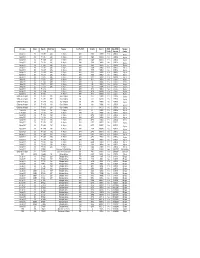

Mfr & Type Variant Reg. No. Build Year Operator Acft Op ICAO Serial No Mode S RVSM Date RVSM Operator Yes/No Approval Country Boeing 737 800 7T - VJK 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30203 0A0019 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJL 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30204 0A001A Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJM 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30205 0A001B Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJN 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30206 0A0020 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJQ 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30207 0A0021 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJP 2001 Air Algérie DAH 30208 0A0022 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJR 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30545 0A0025 Yes 01/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJS 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30210 0A0026 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJT 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30546 0A0027 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJU 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30211 0A0028 Yes 06/07/02 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJV 2005 Air Algérie DAH 0644 0A0044 Yes 31/01/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJW 2005 Air Algérie DAH 647 0A0045 Yes 05/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJY 2005 Air Algérie DAH 653 0A0047 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJX 2005 Air Algérie DAH 650 0A0046 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKA Air Algérie DAH 34164 0A0049 Yes 23/07/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKB Air Algérie DAH 34165 0A004A Yes 22/08/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKC Air Algérie DAH 34166 0A004B Yes 24/08/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP 7T - VPC 2001 Gouv of Algeria IGA 1418 0A4009 Yes 27/07/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP -

Check-In Am Bahnhof Und Fly Rail Baggage

1/8 Check-in am Bahnhof via Zürich und Genève Check-in à la gare via Zürich et Genève Check-in alla stazione via Zürich e Genève Check-in at the railstation via Zürich and Genève Version: 26. Januar 2011 Legend HA = Handlingagent SP = Swissport, DN = Dnata Switzerland AG, AS = Airline Assistance Switzerland AG, EH = Own Handling R = Reason T = Technical, S = Security, O = Other reason WT = Weight Tolerance Y = Economy-Class, C = Business-Class, F = First-Class * = Agent Informations Infoportal/Airlines Check-in ok Restrictions Airline, Code Check-in Einschränkungen/Restrictions WT HA R Y = 2 Adria Airways JP ok SP C = 3 Aegean Airlines A3 ok 2 SP Aer Lingus EI no SP O Aeroflot Russian Airlines SU no SP S Aerolineas Argentinas AR ok 2 SP African Safari Airways ASA ok 2 DN Afriqiyah Airways 8U no DN O Air Algérie* AH ok No boardingpass 0 SP Air Baltic BT no SP T Not for USA, Canada, Pristina, Russia, Air Berlin* AB ok Cyprus; 0 DN not possible for groups 11+ Air Cairo MSC ok 2 SP AC 6821 / 6822 / 6826 / 6829 / 6832 / Air Canada AC no SP T =ok Air Dolomiti EN ok 2 SP Air Europa AEA / UX ok 2 DN Not from Zürich; not for USA, Canada, AF ok* 2 SP T Air France* Mexico; no boardingpass Air India AI ok 2 SP Air Italy I9 ok 2 DN Air Mali XG no SP O Air Malta KM ok 3 SP Y = 7 Air Mauritius MK ok Not from Zurich SP C = 10 Air Mediteranée BIE ok 2 DN Air New Zealand NZ ok 2 SP Air One AP ok 2 SP Air Seychelles HM ok Not from Zurich 3 SP Air Transat TS ok 2 SP Alitalia AZ no SP/DN T American Airlines AA no SP T ANA All Nippon Airways NH ok 2 SP Armavia -

Airliner Census Western-Built Jet and Turboprop Airliners

World airliner census Western-built jet and turboprop airliners AEROSPATIALE (NORD) 262 7 Lufthansa (600R) 2 Biman Bangladesh Airlines (300) 4 Tarom (300) 2 Africa 3 MNG Airlines (B4) 2 China Eastern Airlines (200) 3 Turkish Airlines (THY) (200) 1 Equatorial Int’l Airlines (A) 1 MNG Airlines (B4 Freighter) 5 Emirates (300) 1 Turkish Airlines (THY) (300) 5 Int’l Trans Air Business (A) 1 MNG Airlines (F4) 3 Emirates (300F) 3 Turkish Airlines (THY) (300F) 1 Trans Service Airlift (B) 1 Monarch Airlines (600R) 4 Iran Air (200) 6 Uzbekistan Airways (300) 3 North/South America 4 Olympic Airlines (600R) 1 Iran Air (300) 2 White (300) 1 Aerolineas Sosa (A) 3 Onur Air (600R) 6 Iraqi Airways (300) (5) North/South America 81 RACSA (A) 1 Onur Air (B2) 1 Jordan Aviation (200) 1 Aerolineas Argentinas (300) 2 AEROSPATIALE (SUD) CARAVELLE 2 Onur Air (B4) 5 Jordan Aviation (300) 1 Air Transat (300) 11 Europe 2 Pan Air (B4 Freighter) 2 Kuwait Airways (300) 4 FedEx Express (200F) 49 WaltAir (10B) 1 Saga Airlines (B2) 1 Mahan Air (300) 2 FedEx Express (300) 7 WaltAir (11R) 1 TNT Airways (B4 Freighter) 4 Miat Mongolian Airlines (300) 1 FedEx Express (300F) 12 AIRBUS A300 408 (8) North/South America 166 (7) Pakistan Int’l Airlines (300) 12 AIRBUS A318-100 30 (48) Africa 14 Aero Union (B4 Freighter) 4 Royal Jordanian (300) 4 Europe 13 (9) Egyptair (600R) 1 American Airlines (600R) 34 Royal Jordanian (300F) 2 Air France 13 (5) Egyptair (600R Freighter) 1 ASTAR Air Cargo (B4 Freighter) 6 Yemenia (300) 4 Tarom (4) Egyptair (B4 Freighter) 2 Express.net Airlines -

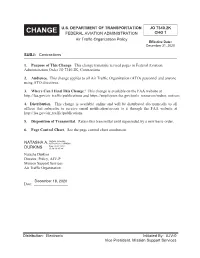

CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 2 Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: November 8, 2018

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2H CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 2 Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: November 8, 2018 SUBJ: Contractions 1. Purpose of This Change. This change transmits revised pages to Federal Aviation Administration Order JO 7340.2H, Contractions. 2. Audience. This change applies to all Air Traffic Organization (ATO) personnel and anyone using ATO directives. 3. Where Can I Find This Change? This change is available on the FAA website at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications and https://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices. 4. Distribution. This change is available online and will be distributed electronically to all offices that subscribe to receive email notification/access to it through the FAA website at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications. 5. Disposition of Transmittal. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. Page Control Chart. See the page control chart attachment. Original Signed By: Sharon Kurywchak Sharon Kurywchak Acting Director, Air Traffic Procedures Mission Support Services Air Traffic Organization Date: October 19, 2018 Distribution: Electronic Initiated By: AJV-0 Vice President, Mission Support Services 11/8/18 JO 7340.2H CHG 2 PAGE CONTROL CHART Change 2 REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−38............ 7/19/18 CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−18........... 11/8/18 3−1−1 through 3−4−1................... 7/19/18 3−1−1 through 3−4−1.................. 11/8/18 Page Control Chart i 11/8/18 JO 7340.2H CHG 2 CHANGES, ADDITIONS, AND MODIFICATIONS Chapter 3. ICAO AIRCRAFT COMPANY/TELEPHONY/THREE-LETTER DESIGNATOR AND U.S. -

User Guide Volume 2

CHANGES TO CODING FRAMES - FEBRUARY 2000 TO JANUARY 2001 NB: the previous note indicated changes for February 1999 to January 2000. A1 & A1(2) - Country codes There are NO NEW CODES from February 2000. A2, A3 & A3(2) - County/Unitary Authority/London Borough & Town codes From January 2001, the 3-digit county/unitary authority/London Borough codes on A2 (Q6) are being replaced by 5-digit codes in line with the town codes on A3 (Q60). Of course, the first 3 digits of the town code are the same as the old county code. However, there are some exceptions: On the A2 (Q6), London Borough codes 066 – 097, and 098 (Barking & Dagenham – Wandsworth, and London Borough not known) have been deleted and are replaced by the following codes: Barking & Dagenham 70100 Barnet 70200 Bexley 70300 Brent 70400 Bromley 70500 Camden 70600 City of London/Westminster 70700 Croydon 70800 Ealing 70900 Enfield 71000 Greenwich 71100 Hackney 71200 Hammersmith & Fulham 71300 Haringey 71400 Harrow 71500 Havering 71600 Hillingdon 71700 Hounslow 71800 Islington 71900 Kensington & Chelsea 72000 Kingston upon Thames 72100 Lambeth 72200 Lewisham 72300 Merton 72400 Newham 72500 Redbridge 72600 Richmond upon Thames 72700 Southwark 72800 Sutton 72900 Tower Hamlets 73000 Waltham Forest 73100 Wandsworth 73200 DK London Borough 79900 On A3 (Q60), Greater London still has the town code 77777. On both A2 and A3 , Northern Ireland-all towns, formerly coded 600 at Q6 and 99993 at Q60, is now coded 60000. Also from January 2001, the following town codes on A3 (Q60 only) are reinstated for Channel Islands and Isle of Man (to be used when visited by foreign residents on a side-trip): Isle of Man-Other 03800 Douglas – Isle of Man 03801 Peel – Isle of Man 03802 Ramsey - Isle of Man 03803 Kirkmichael – Isle of Man 03804 Castletown – Isle of Man 03805 Guernsey – Channel Islands 04801 Alderney – Channel Islands 04802 Sark – Channel Islands 04803 Jersey - Channel Islands 04900 On A2 (Q6), DK Town/County/Unitary Authority is now coded 99999. -

Integration Flow Management and Operations Efficiency: a Study of the Aviation Industry in Kenya

INTEGRATION FLOW MANAGEMENT AND OPERATIONS EFFICIENCY: A STUDY OF THE AVIATION INDUSTRY IN KENYA NELSON DALI IMBITI A Research Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the award of the Degree of Master of Business Administration, School of Business, University of Nairobi NOVEMBER, 2016 DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been submitted for the award of a degree or any other qualification in any other university. Signature Date NELSON DALI IMBITI D61/71148/2014 This research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University Supervisor. Signature Date DR. X.N IRAKI LECTURER, DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I thank God Almighty for seeing me through the MBA program. My sincere gratitude also goes to my supervisor DR. X.N Iraki and Moderator Mr. Onserio Nyamwange for providing unlimited, invaluable and active guidance throughout his project. I also thank the University of Nairobi for giving me an opportunity to pursue my MBA degree at this precious Institution. I thank my family for their prayers, support, and encouragement as I was pursuing this program. I owe a great deal of gratitude to my colleagues at my workplace for their unfailing moral support throughout the period of study and for understanding the demands of the course in terms of time. I also appreciate the contributions of all the respondents towards the success of this project. God bless you all. iii DEDICATION To my son, Einstein Imbiti iv ABSTRACT The essential impacts of flow management originate from a mutual understanding, greater transparency, as well as an improved communication coupled with the information and material flows. -

I EFFECT of TAX INCENTIVES on FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF

i EFFECT OF TAX INCENTIVES ON FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF DOMESTIC AIRLINES IN KENYA BY JOHN GATURO CHEGE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF TAX AND CUSTOMS (TAX OPTION) MOI UNVERSITY 2020 ii DECLARATION Declaration by Candidate I declare that this is my original work and has not been presented in higher learning institutions for a degree or any other award. No part of this thesis may be reproduced in any form without prior permission of the author and/or Moi University. Signature_________________________ Date________________________ JOHN GATURO CHEGE KESRA/105/0055/2017 Declaration by the Supervisor This thesis has been submitted with my approval as the university supervisor. Signature_________________________ Date________________________ DR. MARION NEKESA, Ph.D. Department of Accounting and Finance School of Business, Moi University Signature_________________________ Date________________________ DR. CHEBOI YEGON, Ph.D. Department of Accounting and Finance School of Business, Moi University iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I thank the Almighty God for the free gift of life, good health and strength without which this work could not be in existence. I am very grateful to my supervisor for the guidance and support. iv DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my friends and family v ABSTRACT The profitability of the airlines in Kenya has been dismal over the years unlike their counterparts in the region. Studies relating to effect of tax incentives were done in developed and other developing countries other than Kenya. Similarly, some of these studies did not focus on domestic airlines. -

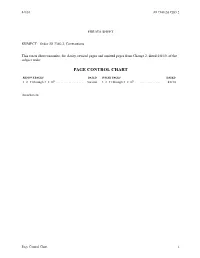

Page Control Chart

4/8/10 JO 7340.2A CHG 2 ERRATA SHEET SUBJECT: Order JO 7340.2, Contractions This errata sheet transmits, for clarity, revised pages and omitted pages from Change 2, dated 4/8/10, of the subject order. PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED 3−2−31 through 3−2−87 . various 3−2−31 through 3−2−87 . 4/8/10 Attachment Page Control Chart i 48/27/09/8/10 JO 7340.2AJO 7340.2A CHG 2 Telephony Company Country 3Ltr EQUATORIAL AIR SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE EQL ERAH ERA HELICOPTERS, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ERH ERAM AIR ERAM AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC IRY REPUBLIC OF) ERFOTO ERFOTO PORTUGAL ERF ERICA HELIIBERICA, S.A. SPAIN HRA ERITREAN ERITREAN AIRLINES ERITREA ERT ERTIS SEMEYAVIA KAZAKHSTAN SMK ESEN AIR ESEN AIR KYRGYZSTAN ESD ESPACE ESPACE AVIATION SERVICES DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC EPC OF THE CONGO ESPERANZA AERONAUTICA LA ESPERANZA, S.A. DE C.V. MEXICO ESZ ESRA ELISRA AIRLINES SUDAN RSA ESSO ESSO RESOURCES CANADA LTD. CANADA ERC ESTAIL SN BRUSSELS AIRLINES BELGIUM DAT ESTEBOLIVIA AEROESTE SRL BOLIVIA ROE ESTERLINE CMC ELECTRONICS, INC. (MONTREAL, CANADA) CANADA CMC ESTONIAN ESTONIAN AIR ESTONIA ELL ESTRELLAS ESTRELLAS DEL AIRE, S.A. DE C.V. MEXICO ETA ETHIOPIAN ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES CORPORATION ETHIOPIA ETH ETIHAD ETIHAD AIRWAYS UNITED ARAB EMIRATES ETD ETRAM ETRAM AIR WING ANGOLA ETM EURAVIATION EURAVIATION ITALY EVN EURO EURO CONTINENTAL AIE, S.L. SPAIN ECN CONTINENTAL EURO EXEC EUROPEAN EXECUTIVE LTD UNITED KINGDOM ETV EURO SUN EURO SUN GUL HAVACILIK ISLETMELERI SANAYI VE TURKEY ESN TICARET A.S. -

Order 7340.1Z, Contractions

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION 7340.1Z CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to change 3 of Order 7340.1Z, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; all air traffic field offices and field facilities; all airway facilities field offices; all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and the interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. February 14, 2008. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Cancellations, additions, and modifications are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the Page Control Chart attachment. Nancy B. Kalinowski Acting Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: __________________ Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 02/14/08 7340.1Z CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM-1-1 and CAM-1-10 10/25/07 CAM-1-1 and CAM-1-2 02/14/08 1-1-1 10/25/07 1-1-1 02/14/08 3-1-15 through 3-1-18 03/15/07 3-1-15 through 3-1-18 02/14/08 3-1-35 03/15/07 3-1-35 03/15/07 3-1-36 03/15/07 3-1-36 02/14/08 3-1-45 03/15/07 3-1-45 02/14/08 3-1-46 10/25/07 3-1-46 10/25/07 3-1-47 -

Air Transport

National Air & Space Museum Technical Reference Files: Air Transport NASM Staff 2017 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 2 Series F0: Air Transport, General............................................................................ 2 Series F1: Air Transport, Airlines........................................................................... 23 Series F2: Air Transport, by Region or Nation..................................................... 182 Series F3: Air Transport, Airports, General.......................................................... 189 Series F4: Air Transport, Airports, USA............................................................... 198 Series F5: Air Transport, Airports, Foreign.......................................................... 236 Series F6: Air Transport, Air Mail......................................................................... 251 National Air & Space Museum Technical Reference Files: Air Transport NASM.XXXX.1183.F Collection Overview Repository: National Air and Space Museum Archives Title: National -

FAA Order JO 7340.2K Contractions

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2K CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 1 Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: December 31, 2020 SUBJ: Contractions 1. Purpose of This Change. This change transmits revised pages to Federal Aviation Administration Order季JO季7340.2K, Contractions. 2. Audience. This change applies to all Air Traffic Organization (ATO) personnel and anyone using ATO directives. 3. Where Can I Find This Change? This change is available on the FAA website at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications and https://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices. 4. Distribution. This change is available online and will be distributed electronically to all offices that subscribe to receive email notification/access to it through the FAA website at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications. 5. Disposition of Transmittal. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. Page Control Chart. See the page control chart attachment. Digitally signed by NATASHA A. NATASHA A. DURKINS Date: 2020.12.18 DURKINS 15:49:13 -05'00' Natasha Durkins Director, Policy$-93 Mission Support Services Air Traffic Organization December 18, 2020 Date: __________________ Distribution: Electronic Initiated By: AJV-0 Vice President, Mission Support Services 12/31/20 JO 7340.2K CHG 1 PAGE CONTROL CHART Change 1 REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−5 ............. 9/10/20 CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−3 ............ 12/31/20 3−1−1 through 3−4−1 ................... 9/10/20 3−1−1 through 3−4−1 .................. 12/31/20 Page Control Chart i 12/31/20 JO 7340.2K CHG 1 CHANGES, ADDITIONS AND MODIFICATIONS Chapter 3. -

No 2588/69 Establishing the List of Airline Companies to Which the Community Transit Guarantee Waiver Applies

No L 271 /24 Official Journal of the European Communities 28 . 9 . 73 REGULATION (EEC) No 2625/73 OF THE COMMISSION of 26 September 1973 amending Regulation ( EEC) No 2588/69 establishing the list of airline companies to which the Community transit guarantee waiver applies THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN companies ; whereas it is necessary to delete from the COMMUNITIES , list airline companies ceasing to operate ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Whereas for practical reasons, it is appropriate to Economic Community ; re-cast the list so that the airline companies are shown in alphabetical order but without numbering ; Having regard to Council Regulation (EEC) No 542/69 ( } ) of 18 March 1969 on Community Transit, Whereas the provisions of this Regulation are in accor and in particular Article 45 thereof ; dance with the Opinion of the Committee on Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No Community Transit ; 2588/69 (2 ) of 22 December 1969 , last amended by the Act (3 ) concerning the Conditions of Accession HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION : and the Adjustments to the Treaties established a list of airline companies exempt from providing the guarantee required within the framework of the Sole Article Community transit system ; The list annexed to this Regulation shall replace the Whereas the reasons governing the establishment of list shown in the Annex to Regulation (EEC) No this list equally leads to the addition of other airline 2588/69 . This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States . Done at Brussels, 26 September 1973 . For the Commission The President Francois-Xavier ORTOLI (') OJ No L 77 , 29 .