Article Eclipsed by the Pleasure Dome: Poetic Failure in Coleridge's 'Kubla Khan'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democracy’ in Somerset and Beyond

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89755-6 - Romanticism, Revolution and Language: The Fate of the Word from Samuel Johnson to George Eliot John Beer Excerpt More information chapter 1 ‘Democracy’ in Somerset and beyond The political impact of the French Revolution in England was strangely oblique, even when one remembers that it was largely being experienced at one remove. My concern here is not only with some examples of that oblique reaction but with language generally, and with the manner in which the growing questioning of authority during the period reflected a more profound alteration, taking place over a much longer period – a movement from what might be termed the language of fidelity to the cultivation of dialects that could be regarded as more critically oriented. To put the matter another way, whereas in medieval times writers had been so close to the religion of their surrounding culture that they did not need to think about the possible religious implications of their language, by the middle of the twentieth century, they would have become so self-conscious and self-critical that they could not write anything containing such implications and not be aware of possible commenting voices ranging from the harshly critical to the warmly favourable. The 1790s, I shall maintain, provided a crucial juncture for this development. In addition, however, attention may be drawn to recent emphases in the writing of history by which the possibility of concentrating on a small and particular detail and expanding one’s attention from there can be explored, or, alternately, one may begin by proceeding to the widest possible extreme and moving inward. -

Saving Sarah Fricker: Accurately Representing the Realities of the Coleridges’ Marriage

Saving Sarah Fricker: Accurately Representing the Realities of the Coleridges’ Marriage Saving Sarah Fricker: Accurately Representing the Realities of the Coleridges’ Marriage Cori Mathis Abstract The Lake Poets circle was prolific; they wrote letters to each other constantly, leaving a clear picture of the beginning and eventual decline of the marriage between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Sarah Fricker Coleridge. Coleridge also was fond of chronicling his personal life in his work. Coleridge’s poetry and prose clearly show that, though he may have come to regret it, he originally married Sarah Fricker for love and was very happy in the beginning of their relationship. The problem with their marriage was that they were just fundamentally incompatible, something that was not Sarah Fricker’s fault—she was a product of her society and simply unprepared to be a wife to someone like Coleridge. Unfortunately, scholars have taken Coleridge’s letters as pure truth and seem to have forgotten that every marriage has two partners, both with their own perspectives. This reflects a deliberate ignorance of Coleridge’s tendency to see situations quite differently from how they actually were. Because of this tradition, Sarah Fricker Coleridge is often portrayed as difficult at best and a harridan at worst. It does not help that she attempted to help her husband’s reputation by the majority of their letters that she possessed—one cannot see her side as clearly. In this essay, I hope to prove that she was simply an unhappy wife, married to a poetic genius who had decided she was the impediment to his happiness while she only wanted to keep their family together and safe. -

Rulers of Opinion Women at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, 1799

Rulers of Opinion Women at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, 1799-1812 Harriet Olivia Lloyd UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Science 2018 1 I, Harriet Olivia Lloyd, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the role of women at the Royal Institution of Great Britain in its first decade and contributes to the field by writing more women into the history of science. Using the method of prosopography, 844 women have been identified as subscribers to the Royal Institution from its founding on 7 March 1799, until 10 April 1812, the date of the last lecture given by the chemist Humphry Davy (1778- 1829). Evidence suggests that around half of Davy’s audience at the Royal Institution were women from the upper and middle classes. This female audience was gathered by the Royal Institution’s distinguished patronesses, who included Mary Mee, Viscountess Palmerston (1752-1805) and the chemist Elizabeth Anne, Lady Hippisley (1762/3-1843). A further original contribution of this thesis is to explain why women subscribed to the Royal Institution from the audience perspective. First, Linda Colley’s concept of the “service élite” is used to explain why an institution that aimed to apply science to the “common purposes of life” appealed to fashionable women like the distinguished patronesses. These women were “rulers of opinion,” women who could influence their peers and transform the image of a degenerate ruling class to that of an élite that served the nation. -

ABSTRACT Genius, Heredity, and Family Dynamics. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and His Children: a Literary Biography Yolanda J. Gonz

ABSTRACT Genius, Heredity, and Family Dynamics. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his Children: A Literary Biography Yolanda J. Gonzalez, Ph.D. Chairperson: Stephen Prickett, Ph.D. The children of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Hartley, Derwent, and Sara, have received limited scholarly attention, though all were important nineteenth century figures. Lack of scholarly attention on them can be blamed on their father, who has so overshadowed his children that their value has been relegated to what they can reveal about him, the literary genius. Scholars who have studied the children for these purposes all assume familial ties justify their basic premise, that Coleridge can be understood by examining the children he raised. But in this case, the assumption is false; Coleridge had little interaction with his children overall, and the task of raising them was left to their mother, Sara, her sister Edith, and Edith’s husband, Robert Southey. While studies of S. T. C.’s children that seek to provide information about him are fruitless, more productive scholarly work can be done examining the lives and contributions of Hartley, Derwent, and Sara to their age. This dissertation is a starting point for reinvestigating Coleridge’s children and analyzes their life and work. Taken out from under the shadow of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, we find that Hartley was not doomed to be a “child of romanticism” as a result of his father’s experimental approach to his education; rather, he chose this persona for himself. Conversely, Derwent is the black sheep of the family and consciously chooses not to undertake the family profession, writing poetry. -

Paratextual and Bibliographic Traces of the Other Reader in British Literature, 1760-1897

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 9-22-2019 Beyond The Words: Paratextual And Bibliographic Traces Of The Other Reader In British Literature, 1760-1897 Jeffrey Duane Rients Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rients, Jeffrey Duane, "Beyond The Words: Paratextual And Bibliographic Traces Of The Other Reader In British Literature, 1760-1897" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1174. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1174 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEYOND THE WORDS: PARATEXTUAL AND BIBLIOGRAPHIC TRACES OF THE OTHER READER IN BRITISH LITERATURE, 1760-1897 JEFFREY DUANE RIENTS 292 Pages Over the course of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, compounding technological improvements and expanding education result in unprecedented growth of the reading audience in Britain. This expansion creates a new relationship with the author, opening the horizon of the authorial imagination beyond the discourse community from which the author and the text originate. The relational gap between the author and this new audience manifests as the Other Reader, an anxiety formation that the author reacts to and attempts to preempt. This dissertation tracks these reactions via several authorial strategies that address the alienation of the Other Reader, including the use of prefaces, footnotes, margin notes, asterisks, and poioumena. -

Somerset Parish Registers. Marriages

942.38019 W!E^ Aalp V.6 1379239 GENEALOGY eOL LECTION ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 00676 1198 ) SOMERSET PARISH REGISTERS. nDarriagee, VI. PHILLIMORE S PARISH RKGISTER SERIES. VOL. VI. (SOMERSET, VOL. LIV. (Jni- hundred and fifty only printed. O. (P'^ : Somerset I ^ Parish Registers. ilDarriages. Edited by W. P. W. PHILLIMORE, M.A., B.C.L., AND W. A. BELL, Rector of Chavlynch, AND C. W. WHISTLER, M.R.C.S., Vicay of Stockland. VOL. VI. 5o XonDon Issued to the Subscribers by Phillimore & Co., 124, Chancery Lane, 1905. ^ — ^^ i s PREFACE. A sixth volume of Somerset Marriage Registers is now completed, making the total number of parishes dealt with to be forty-nine. JL37^9^39 As before, contractions have been made use of w.—widower or widow. dioc.—in the diocese of. b.—bachelor co.—in the county of. s. —spinster, single woman. lie. —marriage licence, d. —daughter. y.—yeoman, p.—of the parish of. c.—carpenter. The reader must remember that the printed volumes are not " evidence " in the legal sense. Certificates must be obtained from the local clergy in charge of the Registers. The Editors have to acknowledge the ready willingness of the Clergy in affording facilities for making the needful transcripts for the printers. Their names are given under the respective parishes. They will gladly welcome the assistance of others who may be willing to aid in transcribing Registers, for it is only by volunteer work that it is possible to print our Parish Registers. They would gladly issue two volumes in each year, and this they can do if those who have the opportunity will supply them with the needful transcriptions of the Registers. -

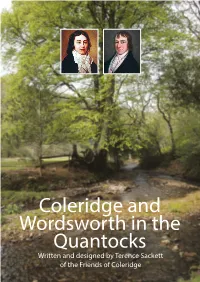

Coleridge and Wordsworth in the Quantocks

Coleridge and Wordsworth in the Quantocks Written and designed by Terence Sackett of the Friends of Coleridge Why did the two poets choose the Quantocks? Samuel Taylor Coleridge first visited Nether Stowey in 1794, while on a walking A fine country house for the Wordsworths tour of Somerset with the poet Robert Southey. Crossing the River Parrett at Coleridge first met William Wordsworth in Combwich, they visited Coleridge’s Cambridge friend Henry Poole at Shurton. Bristol. The two poets took to each other Henry Poole took them to Nether Stowey where Coleridge was introduced to immediately. the man who was to be his most faithful friend and supporter – the tanner and In 1797 Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy Stowey benefactor Thomas Poole. were renting a country house at Racedown Poole accompanied them on a visit to the home of his conventional cousins at in West Dorset. Coleridge, keen to renew nearby Marshmills. The poets shocked them with their radical republican views and deepen the friendship, rushed down to and support for the French Revolution – England was at war with France at the persuade them to move to the Quantocks. Thomas Poole time and there was a serious threat of a French invasion. They found his enthusiasm impossible to resist. Once again Tom Poole was given the task CHRISTIE’S A poor choice of cottage of finding a house for the Wordsworths to Alfoxden House, near Holford to rent. Alfoxden, just outside the village of In 1796 Samuel Taylor Coleridge was living in Bristol. ‘There is everything here, sea, woods wild as fancy Holford and four miles from Stowey, could In his characteristically courageous and foolhardy ever painted, brooks clear and pebbly as in not have been more different to Gilbards. -

A Poetics of Dissent; Or, Pantisocracy in America Colin Jager

A Poetics of Dissent; or, Pantisocracy in America Colin Jager Theory and Event 10:1 | © 2007 To know a bit more about the threads that trace the ordinary ways and forgotten paths of utopia, it would be better to follow the labor of the poets. -- Jacques Ranciere, Short Voyages to the Land of the People The past can be seized only as an image, which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again. -- Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History 1. "Pantisocracy" was an experiment in radical utopian living, invented in England in the closing years of the eighteenth century by a couple of young poets, never put into practice, and described in later, more sober years with a mixture of embarrassment and shame by the poets and their friends, and with sanctimonious anger by their enemies. In the essay that follows I will interpret Pantisocracy as an example of what I call a "poetics of dissent" -- that is, a literary strategy that makes possible a dissenting politics. Immediately, however, it needs to be made clear that both "literary" and "politics" are understood broadly here; indeed, the politics I pursue is simply the possibility of speaking in a certain way. Moreover this essay bears a complicated relationship to a systematic exposition or exegesis, for although certain thinkers -- Derrida, Ranciere, Benjamin, Hardt and Negri -- appear here, I employ them opportunistically. The goal is to describe Pantisocracy in such a way as to create an historical "image" (in Benjamin's sense of the word) of dissent. -

Select Who's Who

Select Who's Who These brief notes are intended to amplify references in the Chron ology, particularly to individuals not in the public domain. The well-known figures of Wordsworth, Lamb, Southey, Byron, De Quincey and Hazlitt are excluded, as are Mary Lamb and Dorothy Wordsworth, since information about them is readily available elsewhere. Adams, Dr Joseph (1756-1818), physician and editor of the Medical and Physical Journal, published a book on cancer in 1795. In 1805 he became physician to the Smallpox Hospital in London. He recom mended STC to the care of James Gillman in 1816. Aders, Mr and Mrs Charles Mr Aders was a wealthy German mer chant who lived in Euston Square and owned valuable paintings. STC met him during the Highgate years. Mrs Aders, nee Eliza Smith, was a daughter of John Raphael Smith, painter and engraver. STC addressed his poem The Two Founts' to her. The Aders' home housed a fine collection of Italian, early Flemish and German paint ings. Samuel Palmer visited in the 1820s, as did Charles Lamb, who wrote a poem describing it as a chapel. Allen Robert (1772-1805), known as 'Bob Allen', was an army sur geon and journalist. He was at Christ's Hospital with STC, and went on as a sizar to University College, Oxford, where STC visited him in 1794; Allen introduced him to Southey of Balliol. He became inter ested in Pantisocracy, but defected by the end of the year. STC wrote in his defence to Southey, 'He did never promise to form one of our party' (Letters, !. -

6 X 10.Three Lines .P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89755-6 - Romanticism, Revolution and Language: The Fate of the Word from Samuel Johnson to George Eliot John Beer Excerpt More information chapter 1 ‘Democracy’ in Somerset and beyond The political impact of the French Revolution in England was strangely oblique, even when one remembers that it was largely being experienced at one remove. My concern here is not only with some examples of that oblique reaction but with language generally, and with the manner in which the growing questioning of authority during the period reflected a more profound alteration, taking place over a much longer period – a movement from what might be termed the language of fidelity to the cultivation of dialects that could be regarded as more critically oriented. To put the matter another way, whereas in medieval times writers had been so close to the religion of their surrounding culture that they did not need to think about the possible religious implications of their language, by the middle of the twentieth century, they would have become so self-conscious and self-critical that they could not write anything containing such implications and not be aware of possible commenting voices ranging from the harshly critical to the warmly favourable. The 1790s, I shall maintain, provided a crucial juncture for this development. In addition, however, attention may be drawn to recent emphases in the writing of history by which the possibility of concentrating on a small and particular detail and expanding one’s attention from there can be explored, or, alternately, one may begin by proceeding to the widest possible extreme and moving inward. -

A Reading of William Wordsworth's "Lucy" Poems

WILLIAM AND DOROTHY: THE POET AND LUCY A READING OF WILLIAM WORDSWORTH'S "LUCY" POEMS Elizabeth Gowland B.A. (Hons.), Simon Fraser University, 1975 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the department 0f English 0 Elizabeth Gowland 1980 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY April, 1980 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Elizabeth Anne GOWLAND Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: William and Dorothy: The Poet and Lucy A Reading of William Wordsworth's "Lucy" Poems Exami ning Commi ttee : Chai rperson: Paul Del any - r --* .. r T7T -\ Jared Curtis , Senior Supervisor Rob Dunham, Associate Professor Mason Harris , Associate Professor June Sturrock, External Examiner Dept. of Continuing Studies, S. F.U. Date Approved: &5'4.@0 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

27 OFTEN DOWN, BUT NEVER OUT SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE (1772-1834) n his quest for a livelihood, in his family life, and in his response to the Enlightenment, the Ipoet and critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge is the contrary of the lesser writer Sydney Smith. His gi- ant weeping willow overshadows Smith’s modest hawthorn, and his letters, unlike Smith’s, are the letters of an unhappy man. Coleridge’s troubles begin in childhood. In 1781, on the threshold of his ninth year, the death of his father, the Vicar of Ottery in Devon, leaves him in the charge of his brother George. After be- ing schooled at Christ’s Hospital, he goes up to Jesus College, Cambridge, where he distinguishes himself as a scholar; falls in love with Mary Evans, whose mother tends him with maternal affection when he is ill; and indulg- es in enough wayward behaviour to pile up debts he cannot pay. During a three-year period beginning when he is eighteen, he lapses from chastity in his association with loose women. In despair and shame, resisting the temptation of suicide, he enlists in the dragoons, or light cavalry, under the name Silas Tomkyn Comberbache. His friends and family succeed in trac- ing him, and after much difficulty his brothers George and James procure his discharge, ostensibly on the grounds of his insanity. Soon after returning to Cambridge, Coleridge meets Robert Southey, and the two young poets, both radicals, concoct a scheme only a little less hare-brained than the flight into the military. With other enthusiasts, they will found a Utopian colony in the United States of America to practise pantisocracy (the rule of all as equals) and aspheterism (commonality of property).