UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biennals 10-13 CUBAN

Iniva: Stuart Hall Library: Select Bibliography 2008 States of Exchange: Artists from Cuba/ Estados de Intercambio: Artistas de Cuba Jeanette Chávez Autocensura / Self-Censorship , 2006 Video, 2:52 min Image courtesy of the artist CONTENTS CUBAN ARTISTS 2-7 CUBAN ART 7-9 CUBAN ART: Biennals 10-13 CUBAN ART: Biennals: Journal articles 13 CUBA ART: Context 14-15 Iniva: Stuart Hall Library: Select Bibliography 2008 States of Exchange: Artists from Cuba/ Estados de Intercambio: Artistas de Cuba ITEM LIBRARY SHELF NUMBER CUBAN ARTISTS Alfonzo, Carlos AS ALF Viso, Olga M. (ed.) Triumph of the Spirit, Carlos Alfonzo: a survey 1975-1991 . Miami: Miami Art Museum 1998. Bedia, Jose AS BED Jose Bedia: Fabula . Bogota: Galeria Fernando Quintana, 1993. Brugera, Tania AS BRU Tania Bruguera: esercizio di resistenza = exercise in resistance . Turin: Franco Soffiantino Arte Contemporanea, 2004. Campos-Pons, Maria Magdalena AS CAM Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons: meanwhile, the girls were playing . Cambridge Mass.: MIT List Visual Arts Centre, 2000. Capote, Ivan AS CAP Ivan Capote . Herausgabe: Havana Edition, 2007. Ivan Capote: Aforismos . AS CAP Cuba: Galeria Habana, 2007. Capote, Yoan AS CAP Yoan Ca pote. Herausgabe: Havana Edition, 2007. Carmona, Williams AS CAR Todos miran, pocos ven /they all look, but few only see . [Paris]: Corinne Timsit International Galleries, [n.d.] Castro, Humberto AS CAS Humberto Castro: le radeau d'Ulysse Paris: Le monde de l'art, [n.d.] [Text in French] Ceballos, Sandra AS CEB Ceballos, Sandra and Suárez, Ezequiel (curs.) Dónde está Loló: Pinturas: Sandra Ceballos . La Habana: Centro Wifredo Lam, 1995. Text in Spanish] 2 Iniva: Stuart Hall Library: Select Bibliography 2008 States of Exchange: Artists from Cuba/ Estados de Intercambio: Artistas de Cuba ITEM LIBRARY SHELF NUMBER Cuenca, Arturo AS CUE Arturo Cuenca: Modernbundo . -

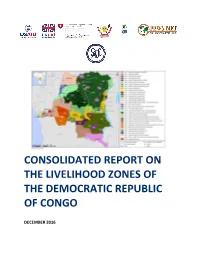

DRC Consolidated Zoning Report

CONSOLIDATED REPORT ON THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DECEMBER 2016 Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Livelihoods zoning ....................................................................................................................7 1.2 Implementation of the livelihood zoning ...................................................................................8 2. RURAL LIVELIHOODS IN DRC - AN OVERVIEW .................................................................. 11 2.1 The geographical context ........................................................................................................ 11 2.2 The shared context of the livelihood zones ............................................................................. 14 2.3 Food security questions ......................................................................................................... 16 3. SUMMARY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES .................................................... 18 CD01 COPPERBELT AND MARGINAL AGRICULTURE ....................................................................... 18 CD01: Seasonal calendar .................................................................................................................... -

DRC)....6 Demographic and Health Situation

UNESCO REVIEW OF HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS’ RESPONSES TO HIV AND AIDS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO– The Case of the University of Kinshasa Case Study conducted by Patrick Kayembé Technical Coordinators of the case study at the Association of African Universities (AAU): Alice Lamptey, Terry Amuzu September, 2005 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNESCO. Table of contents List of Abbreviations..............................................................................................................................................2 Executive Summary................................................................................................................................................3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................5 Methods used:.........................................................................................................................................................5 A. NATIONAL CONTEXT OF HIV/AIDS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC)....6 Demographic and health situation......................................................................................................................6 Scale of the HIV epidemic and trends ...............................................................................................................7 National response...............................................................................................................................................8 -

Directors Fortnight Cannes 2000 Winner Best Feature

DIRECTORS WINNER FORTNIGHT BEST FEATURE CANNES PAN-AFRICAN FILM 2000 FESTIVAL L.A. A FILM BY RAOUL PECK A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE JACQUES BIDOU presents A FILM BY RAOUL PECK Patrice Lumumba Eriq Ebouaney Joseph Mobutu Alex Descas Maurice Mpolo Théophile Moussa Sowié Joseph Kasa Vubu Maka Kotto Godefroid Munungo Dieudonné Kabongo Moïse Tshombe Pascal Nzonzi Walter J. Ganshof Van der Meersch André Debaar Joseph Okito Cheik Doukouré Thomas Kanza Oumar Diop Makena Pauline Lumumba Mariam Kaba General Emile Janssens Rudi Delhem Director Raoul Peck Screenplay Raoul Peck Pascal Bonitzer Music Jean-Claude Petit Executive Producer Jacques Bidou Production Manager Patrick Meunier Marianne Dumoulin Director of Photography Bernard Lutic 1st Assistant Director Jacques Cluzard Casting Sylvie Brocheré Artistic Director Denis Renault Art DIrector André Fonsny Costumes Charlotte David Editor Jacques Comets Sound Mixer Jean-Pierre Laforce Filmed in Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Belgium A French/Belgian/Haitian/German co-production, 2000 In French with English subtitles 35mm • Color • Dolby Stereo SRD • 1:1.85 • 3144 meters Running time: 115 mins A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE 247 CENTRE ST • 2ND FL • NEW YORK • NY 10013 www.zeitgeistfilm.com • [email protected] (212) 274-1989 • FAX (212) 274-1644 At the Berlin Conference of 1885, Europe divided up the African continent. The Congo became the personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium. On June 30, 1960, a young self-taught nationalist, Patrice Lumumba, became, at age 36, the first head of government of the new independent state. He would last two months in office. This is a true story. SYNOPSIS LUMUMBA is a gripping political thriller which tells the story of the legendary African leader Patrice Emery Lumumba. -

View a PDF Programme

Speaker bios Bani Abidi is a visual artist working with video, photography, drawing and sound. She lives in Berlin and Karachi. Recent solo shows include: ‘Funland’, Sharjah Art Foundation, Sharjah; ‘Bani Abidi - They died laughing’, Gropius Bau, Berlin; ‘Bani Abidi - Exercise in Redirecting Lines’ Kunsthaus Hamburg, Hamburg and ‘Bani Abidi – Look at the city from here’, Gandhara Art Foundation, Karachi. Group shows include Karachi Biennial (2018), Busan Biennale (2018), Edinburgh Arts Festival Commissions (2016), 8th Berlin Biennial (2014) and DOCUMENTA 13 (2012). Her work is in the permanent collections of Tate Modern, Museum of Modern Art NY, Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Guggenheim Museum and the British Museum. Iftikhar Dadi & Elizabeth Dadi have collaborated in their art practice for twenty years. Their work investigates memory, borders, and identity in contemporary globalization, the productive capacities of urban informalities in the Global South, and the mass culture of postindustrial societies. Exhibitions include the 24th Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil (1998); The Third Asia-Pacific Triennial, Brisbane, Australia (1999); Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (2000); Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (2000); Liverpool Biennial, Tate Liverpool (2002); Moderna Museet-Stockholm (2005); Whitechapel Gallery, London (2010); Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Japan (2012); Art Gallery of Windsor, Canada (2013); Dhaka Art Summit (2016); Office of Contemporary Art Norway, Oslo (2016); Lahore Biennale 01 (2018); and the Havana Biennial (2019). Iftikhar Dadi is an associate professor in Cornell’s Department of History of Art and Director of the South Asia Program, and a board member of the Institute for Comparative Modernities. He is the author of Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia (2010) and the edited monograph Anwar Jalal Shemza (2015). -

Heri Dono the World and I

FINE ART HERI DONO THE WORLD AND I Jalasveva Jaya Mahe, 2013 Flying Angels, 1996 Tyler Rollins Fine Art is pleased to host the first New York solo exhibition for Heri Dono, taking place from October 30 – December 20, 2014. Entitled The World and I, the exhibition features an overview of paintings, sculptures, and installations from throughout his thirty- year career. It follows a major mid-career survey of Dono’s work, The World and I: Heri Dono’s Art Odyssey, on view earlier this year at Art 1: New Museum in Jakarta, Indonesia, for which a 260 page catalogue was published. One of Indonesia’s most well known and internationally active contemporary artists, Dono has achieved iconic status both internationally and in his native Indonesia. Born in Jakarta in 1960, and a graduate of the Indonesian Institute of the Arts in Yogyakarta, Dono early on developed a distinctive style that came out of his extensive experimentation with the most popular form of Javanese folk theatre, wayang, a vibrant and eclectic art form that enacts complex narratives, often derived from ancient mythology, incorporating music with performances by two-dimensional shadow puppets as well as more lifelike wooden puppets and even human actors. Dono’s elaborate sculptural installations take inspiration from these puppets, bringing them into the contemporary world of machines, robots, and television. Often featuring unusual juxtapositions of motifs, a variety of moving parts, and sound and video components, these multi-media works make powerful statements about political and social issues as well as the often jarring interrelationship between globalization and local cultures. -

Common Humanitarian Fund, DRC Annual Report 2014

Common Humanitarian Fund, DRC Annual Report 2014 Annual Report 2014 Annual DRC Common Humanitarian Fund Humanitarian DRCCommon 1 Common Humanitarian Fund, DRC Annual Report 2014 Please send your questions and comments to : Alain Decoux, Joint Humanitarian Finance Unit (JFHU) + 243 81 706 12 00, [email protected] For the latest on-line version of this report and more on the CHF DRC, please visit: www.unocha.org/DRC or www.humanitarianresponse.info/fr/operations/democratic-republic-congo Cover photo: OCHA/Alain Decoux A displaced woman grinding cassava leaves in Tuungane spontaneous site, Komanda, Irumu Territory where more than 20,000 people were displaced due to conflict in the province. Oriental 02/2015. Kinshasa, DRC May, 2015 1 Common Humanitarian Fund, DRC Annual Report 2014 Table of contents Forword by the Humanitarian Coordinator....................................................................................... 3 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 4 2 Humanitarian Response Plan .................................................................................................. 7 3 Information on Contributions .................................................................................................... 8 4 Overview of Allocations .......................................................................................................... 10 4.1 Allocation strategy ......................................................................................................... -

The 2Nd Biennial Festival of Non-Western Contemporary

The 2 nd biennial festival of non-Western contemporary photography 22/09/09 - 22/11/2009 Artistic direction: Anahita Ghabaian Etehadieh Scenography: Patrick Jouin M U S É E D U Q U A I B R A N L Y C O N T A C T S Communications Department Nathalie Mercier, Communications Director 33(0)1 56 61 70 20 • [email protected] Magalie Vernet, Media Relations Manager 33(0)1 56 61 52 87 • [email protected] P R E S S C O N T A C T S Heymann, Renoult Associates 33(0)1 44 61 76 76 • [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] www.quaibranly.fr / www.photoquai.fr CONTENTS Preface by Stéphane Martin, President of the musée du quai Branly page 3 Preface by Anahita Ghabaian Etehadieh, Artistic Director of PHOTOQUAI page 4 I. Presentation of PHOTOQUAI 2009 page 7 II. Organisation of PHOTOQUAI 2009 page 8 III. Selection of works - PHOTOQUAI , the exhibition on the quai Branly page 10 - 165 years of Iranian photography at the musée du quai Branly page 28 - Portraits croisés (comparative portraits) , at the Pavillon des Sessions page 29 IV. The photographic collection of the musée du quai Branly page 30 V. Meetings, screenings, debates page 33 - Meetings with the photographers - Fridays at PHOTOQUAI - PHOTOQUAI School: « Regards croisés » (comparative views) - PHOTOQUAI Forum VI. PHOTOQUAI’s partners page 36 VII. Patrons and sponsors page 48 VIII. Media partners page 49 IX. Annexes - Catalogue page 50 - Curators' biographies page 51 - Photographers’ biographies page 54 - Practical information / Press contacts page 60 www.quaibranly.fr / www.photoquai.fr * PREFACE BY STEPHANE MARTIN Stéphane Martin © musée du quai Branly, photo Greg Semu In 2009, the musée du quai Branly was three years old. -

Mecanisme De Referencement

EN CAS DE VIOLENCE SEXUELLE, VOUS POUVEZ VOUS ORIENTEZ AUX SERVICES CONFIDENTIELLES SUIVANTES : RACONTER A QUELQU’UN CE QUI EST ARRIVE ET DEMANDER DE L’AIDE La/e survivant(e) raconte ce qui lui est arrivé à sa famille, à un ami ou à un membre de la communauté; cette personne accompagne la/e survivant(e) au La/e survivant(e) rapporte elle-même ce qui lui est arrivé à un prestataire de services « point d’entrée » psychosocial ou de santé OPTION 1 : Appeler la ligne d’urgence 122 OPTION 2 : Orientez-vous vers les acteurs suivants REPONSE IMMEDIATE Le prestataire de services doit fournir un environnement sûr et bienveillant à la/e survivant(e) et respecter ses souhaits ainsi que le principe de confidentialité ; demander quels sont ses besoins immédiats ; lui prodiguer des informations claires et honnêtes sur les services disponibles. Si la/e survivant(e) est d'accord et le demande, se procurer son consentement éclairé et procéder aux référencements ; l’accompagner pour l’aider à avoir accès aux services. Point d’entrée médicale/de santé Hôpitaux/Structures permanentes : Province du Haut Katanga ZS Lubumbashi Point d’entrée pour le soutien psychosocial CS KIMBEIMBE, Camps militaire de KIMBEIMBE, route Likasi, Tel : 0810405630 Ville de Lubumbashi ZS KAMPEMBA Division provinciale du Genre, avenue des chutes en face de la Division de Transport, HGR Abricotiers, avenue des Abricotiers coin avenue des plaines, Q/ Bel Air, Bureau 5, Centre ville de Lubumbashi. Tel : 081 7369487, +243811697227 Tel : 0842062911 AFEMDECO, avenue des pommiers, Q/Bel Air, C/KAMPEMBA, Tel : 081 0405630 ZS RUASHI EASD : n°55, Rue 2, C/ KATUBA, Ville de Lubumbashi. -

An Inventory of Fish Species at the Urban Markets of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo

FISHERIES AND HIV/AIDS IN AFRICA: INVESTING IN SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS PROJECT REPORT | 1983 An inventory of fi sh species at the urban markets of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Mujinga, W. • Lwamba, J. • Mutala, S. • Hüsken, S.M.C. • Reducing poverty and hunger by improving fisheries and aquaculture www.worldfi shcenter.org An inventory of fish species at the urban markets of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Mujinga, W., Lwamba, J., Mutala, S. et Hüsken, S.M.C. Translation by Prof. A. Ngosa November 2009 Fisheries and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Investing in Sustainable Solutions This report was produced under the Regional Programme “Fisheries and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Investing in Sustainable Solutions” by the WorldFish Center and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), with financial assistance from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This publication should be cited as: Mujinga, W., Lwamba, J., Mutala, S. and Hüsken, S.M.C. (2009). An inventory of fish species at the urban markets in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Regional Programme Fisheries and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Investing in Sustainable Solutions. The WorldFish Center. Project Report 1983. Authors’ affiliations: W. Mujinga : University of Lubumbashi, Clinique Universitaire. J. Lwamba : University of Lubumbashi, Clinique Universitaire. S. Mutala: The WorldFish Center DRC S.M.C. Hüsken: The WorldFish Center Zambia National Library of Malaysia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Cover design: Vizual Solution © 2010 The WorldFish Center All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational or non-profit purposes without permission of, but with acknowledgment to the author(s) and The WorldFish Center. -

The Re-Mediation of José Redinha's Paredes Pintadas Da Lunda

Accessing the Ancestors: the re-MediAtion of José redinhA’s PAREDES PINTADAS DA LUNDA Delinda Collier, School of the Art Institute of Chicago Alguém varreu o fogo “virgin discs” was saving the Chokwe culture from a minha infância demise at the hands of the Chokwe themselves, e na fogueira arderam todos os ancestres. who, according to him, were discarding their heritage in favor of “newer” musical forms. They (Some fire swept through were denying the traditions of their ancestors, an my childhood ironic characterization of the upheavals that took 1 and the fire burned all of the ancestors.) place in the Lunda region during the rise of the —“Terra Autobiográfica” mining industry and colonial conflict—after all, by Francisco Fernando da Costa 80 percent of Diamang’s workforce was Chokwe, Andrade a large portion of whom were conscripted by the colonial government.3 Vilhena explains that the Dundo Museum was the first line of defense in saving tangible and intangible Chokwe culture. Júlio Vilhena, scholar and son of the then The company’s last resort, he says, was the use Delegate Administrator for the Companhia de of phonographic discs and other media objects Diamantes de Angola (Diamang), wrote an article to record analogical information that could pass for the Journal of the International Folk Music Council through and out of these tropical conditions in 1955, in which he presented a folklore project and into the ether—the non-place safety zone of the Dundo Museum in Lunda North, Angola. of storage media. He comments on the logistics of -

Urban Africa – Urban Africans Picture: Sandra Staudacher New Encounters of the Urban and the Rural

7th European Conference on African Studies ECAS 29 June to 1 July 2017 — University of Basel, Switzerland Urban Africa – Urban Africans Picture: Sandra Staudacher New encounters of the urban and the rural www.ecas2017.ch Convening institutions Institutional partners Funding partners ECAS7 Index 3 Welcome 4 Word from the organisers 5 Organisers 6 A* Magazine 7 Programme overview 10 Keynote speakers 12 Hesseling Prize 14 Round Tables 15 Film Sessions 20 Meetings 24 Presentations and Receptions 25 Book launches 26 Panels details (by number) 28 Detailed programme (by date) 96 List of participants 115 Publisher exhibition 130 Practical information 142 Impressum Cover picture: Street scene in Mwanza, Tanzania Picture by Sandra Staudacher. Graphic design: Strichpunkt GmbH, www.strichpunkt.ch. ___ECAS7_CofrenceBook_.indb 3 12.06.17 17:22 4 Welcome ECAS7 ia, India, South Korea, Japan, and Brazil. Currently it has 29 members, 5 associate members and 4 af- filiate members worldwide. Besides the European Conference on African Studies, by far its major ac- tivity, AEGIS promotes various activities to sup- port African Studies, such as specific training events, summer schools, and thematic conferen- ces. Another initiative, the Collaborative Research Groups (CRGs) is creating links between scholars from AEGIS and non-AEGIS centres that engage in collaborative research in new fields. AEGIS also supports the European Librarians in African Stud- ies (ELIAS). A new initiative, relating scholars in Af- rican Studies with social and economic entrepre- neurship is expressed in initiatives such as Africa Works! (African Studies Centre, Leiden) or the I have the great pleasure of welcoming to the 7th Business and Development Forum held just be- European Conference on African Studies ECAS fore ECAS.