Contia Tenuis) in Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ES Teacher Packet.Indd

PROCESS OF EXTINCTION When we envision the natural environment of the Currently, the world is facing another mass extinction. past, one thing that may come to mind are vast herds However, as opposed to the previous five events, and flocks of a great diversity of animals. In our this extinction is not caused by natural, catastrophic modern world, many of these herds and flocks have changes in environmental conditions. This current been greatly diminished. Hundreds of species of both loss of biodiversity across the globe is due to one plants and animals have become extinct. Why? species — humans. Wildlife, including plants, must now compete with the expanding human population Extinction is a natural process. A species that cannot for basic needs (air, water, food, shelter and space). adapt to changing environmental conditions and/or Human activity has had far-reaching effects on the competition will not survive to reproduce. Eventually world’s ecosystems and the species that depend on the entire species dies out. These extinctions may them, including our own species. happen to only a few species or on a very large scale. Large scale extinctions, in which at least 65 percent of existing species become extinct over a geologically • The population of the planet is now growing by short period of time, are called “mass extinctions” 2.3 people per second (U.S. Census Bureau). (Leakey, 1995). Mass extinctions have occurred five • In mid-2006, world population was estimated to times over the history of life on earth; the first one be 6,555,000,000, with a rate of natural increase occurred approximately 440 million years ago and the of 1.2%. -

PDF Files Before Requesting Examination of Original Lication (Table 2)

often be ingested at night. A subsequent study on the acceptance of dead prey by snakes was undertaken by curator Edward George Boulenger in 1915 (Proc. Zool. POINTS OF VIEW Soc. London 1915:583–587). The situation at the London Zoo becomes clear when one refers to a quote by Mitchell in 1929: “My rule about no living prey being given except with special and direct authority is faithfully kept, and permission has to be given in only the rarest cases, these generally of very delicate or new- Herpetological Review, 2007, 38(3), 273–278. born snakes which are given new-born mice, creatures still blind and entirely un- © 2007 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles conscious of their surroundings.” The Destabilization of North American Colubroid 7 Edward Horatio Girling, head keeper of the snake room in 1852 at the London Zoo, may have been the first zoo snakebite victim. After consuming alcohol in Snake Taxonomy prodigious quantities in the early morning with fellow workers at the Albert Public House on 29 October, he staggered back to the Zoo and announced that he was inspired to grab an Indian cobra a foot behind its head. It bit him on the nose. FRANK T. BURBRINK* Girling was taken to a nearby hospital where current remedies available at the time Biology Department, 2800 Victory Boulevard were tried: artificial respiration and galvanism; he died an hour later. Many re- College of Staten Island/City University of New York spondents to The Times newspaper articles suggested liberal quantities of gin and Staten Island, New York 10314, USA rum for treatment of snakebite but this had already been accomplished in Girling’s *Author for correspondence; e-mail: [email protected] case. -

Snake Surveys in Jackson, Josephine and Southern Douglas Counties, Oregon

Snake Surveys in Jackson, Josephine and Southern Douglas Counties, Oregon JASON REILLY ED MEYERS DAVE CLAYTON RICHARD S. NAUMAN May 5, 2011 For more information contact: Jason Reilly Medford District Bureau of Land Management [email protected] Introduction Southwestern Oregon is recognized for its high levels of biological diversity and endemism (Whittaker 1961, Kaye et al. 1997). The warm climate and broad diversity of habitat types found in Jackson and Josephine counties result in the highest snake diversity across all of Oregon. Of the 15 snake species native to Oregon, 13 occur in the southwestern portion of the state and one species, the night snake, is potentially found here. Three of the species that occur in Oregon: the common kingsnake, the California mountain kingsnake, and the Pacific Coast aquatic garter snake are only found in southwestern Oregon (Table 1, St. John 2002). Table 1. Snakes known from or potentially found in Southwestern Oregon and conservation status. Scientific Name Common Name Special Status Category1 Notes Charina bottae Rubber Boa None Common Sharp-tailed See Feldman and Contia tenuis None Snake Hoyer 2010 Recently described Forest Sharp-tailed Contia longicaudae None species see Feldman Snake and Hoyer 2010 Diadophis Ring-necked Snake None punctatus Coluber constrictor Racer None Masticophis Appears to be very Stripped Whipsnake None taeniatus rare in SW Oregon Pituophis catenifer Gopher Snake None Heritage Rank G5/S3 Lampropeltis Federal SOC Appears to be rare in Common Kingsnake getula ODFW SV SW Oregon ORBIC 4 Heritage Rank G4G5/S3S4 Lampropeltis California Mountain Federal SOC zonata Kingsnake ODFW SV ORBIC 4 Thamnophis sirtalis Common Garter Snake None Thamnophis Northwestern Garter None ordinoides Snake Thamnophis Western Terrestrial None elegans Garter Snake Thamnophis Pacific Coast Aquatic None atratus Garter Snake No records from SW Hypsiglena Oregon. -

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group COMMON SHARP-TAILED SNAKE Contia tenuis Family: COLUBRIDAE Order: SQUAMATA Class: REPTILIA R049 Written by: S. Morey Reviewed by: T. Papenfuss Edited by: R. Duke Updated by: CWHR Staff, February 2008 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY This secretive little snake is common in suitable habitats throughout its range in California. It occurs in the Siskiyou and Cascade ranges in the north, along the Coast Ranges from Eureka in Humboldt Co. to central San Luis Obispo Co. Generally absent from the Central Valley, it is found the length of the Sierra at middle and low elevations on the west slope. Elevation sea level to perhaps 2130 m (7000 ft) in the central and southern Sierra. Occurs in a wide variety of habitats. SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: This snake appears to be specialized for eating slugs (Zweifel 1954). The only recognizable food items found in a series of museum specimens examined by Woodin (unpubl.) were slugs, but Stebbins (1954) suggested that small plethodontid salamanders (Batrachoseps and young Aneides) may also be taken. Cover: Sharp-tailed snakes are seldom seen in the open. Most of their activity takes place under surface objects such as flat rocks, loose bark on logs, woodpiles, and other human debris. Subterranean activity is suggested by the discovery by McLean (1927) of an individual at a depth of 2.5 m (8 ft) underground during construction in the central Sierra foothills. Reproduction: Little is known about habitat requirements for reproduction. Nussbaum et al. (1983) report egg clutches apparently laid in soil from 7 to 15 cm (2.8 to 6 in) deep in rock outcrops and among the roots of grass. -

Chapter 4: Amphibians and Reptiles

1 Chapter 4: Amphibians and Reptiles The history of amphibians, reptiles, and even our own species, is an epic journey through time. But exactly how long? A hundred years ago? A thousand? A million? Well, what about 380 million years ago? Why so long? Well, everything just seems to take a lot longer than we think it should. Just think about how long it takes to get ready in the morning—or do a math assignment! It takes time to move continents, make new species, and change the world. Between 416 and 359 million years ago, the Earth started to change. This time period is called the Devonian. Somewhere around 380 million years ago, the first amphibians began making their way onto land, making them the first animals with a spine to do so. They were able to do this because they had developed lungs - allowing them to breathe oxygen by getting it straight from the air. This was a huge advantage because the oceans were running out of oxygen. Amphibians then, and even now, needed water to lay their eggs. Their eggs are soft and gooey. Without a shell to protect them, they will dry up and die. So remember— if you are trying to find an amphibian, find water first! After the amphibians made their way onto land, some of them started to change again. Some created eggs that had a leathery or hard shell. This one ad- aptation gave rise to the reptiles. Rep- tiles first appear in the Carboniferous period (359.2 million years to about 299.0 million years ago). -

Fish and Wildlife in the Corte Madera Creek Watershed

Fish and Wildlife in the Corte Madera Creek Watershed Prepared by Friends of Corte Madera Watershed May 2004 Many creatures are found in the watershed. The following categories are discussed below: invertebrates, fish, amphibians and reptiles, birds, and mammals. Invertebrates Detailed information regarding the aquatic invertebrate populations is limited to the middle, lower, and tidally influenced portions of the watershed. Information about the Ross area provided by the Corps of Engineers (1987) suggests that the creeks support a diverse aquatic insect population. Insects observed include water striders, water scorpions, giant water bugs, water boatmen, water bugs (Naucoridia and Dytiscidae), diving beetles, whirligigs, Dobson fly larvae, caddis fly larvae, damselfly nymphs, dragonfly nymphs, mayfly nymphs, mosquitoes, gnats, and black flies. Crayfish are commonly observed in the freshwater reaches of the creek. Benthic sampling of the non-tidal reaches of the creek (COE 1987) indicated that dipteran (fly) larvae were numerically dominant. Only a few reaches of the creek supported the generally herbaceous mayfly larvae. Omnivorous coroxid beetles were also noted. Pulmonate snails, invertebrates that are moderately tolerant of pollution, tend to dominate the benthic biomass. Larvae and emergent adult insects are particularly important food sources for young steelhead trout. In the tidal areas of the watershed, the species are typical of those found throughout San Francisco Bay. The two dominant benthic species found in Corte Madera Creek tidal areas are the gem clam (Gemma gemma) and the amphipod Ampelisca abdita. Other species found there were the clam Chone gracilis, the Asian clam (Potamocorbula amurensis), Sipunculid worms, and the small mussel (Musculus senhousia). -

Other Species and Biodiversity of Older Forests

Synthesis of Science to Inform Land Management Within the Northwest Forest Plan Area Chapter 6: Other Species and Biodiversity of Older Forests Bruce G. Marcot, Karen L. Pope, Keith Slauson, findings on amphibians, reptiles, and birds, and on selected Hartwell H. Welsh, Clara A. Wheeler, Matthew J. Reilly, carnivore species including fisher Pekania( pennanti), and William J. Zielinski1 marten (Martes americana), and wolverine (Gulo gulo), and on red tree voles (Arborimus longicaudus) and bats. Introduction We close the section with a brief review of the value of This chapter focuses mostly on terrestrial conditions of spe- early-seral vegetation environments. We next review recent cies and biodiversity associated with late-successional and advances in development of new tools and datasets for old-growth forests in the area of the Northwest Forest Plan species and biodiversity conservation in late-successional (NWFP). We do not address the northern spotted owl (Strix and old-growth forests, and then review recent and ongoing occidentalis caurina) or marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus challenges and opportunities for ameliorating threats marmoratus)—those species and their habitat needs are and addressing dynamic system changes. We end with a covered in chapters 4 and 5, respectively. Also, the NWFP’s set of management considerations drawn from research Aquatic and Riparian Conservation Strategy and associated conducted since the 10-year science synthesis and suggest fish species are addressed in chapter 7, and early-succes- areas of further study. sional vegetation and other conditions are covered more in The general themes reviewed in this chapter were chapters 3 and 12. guided by a set of questions provided by the U.S. -

SQUAMATA: COLUBRIDAE Opheodrys Aestivus (Linnaeus)

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: COLUBRIDAE Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Walley, H.D. and M.V. Plummer. 2000. Opheodrys aestivus. Opheodrys aestivus (Linnaeus) Rough Green Snake Coluber aestivus Linnaeus 1766:387. Type locality, "Carolina," based on a specimen sent to Linnaeus by Alexander Garden. Holotype unknown. Type locality restricted to Charleston, South Carolina by Smith and Taylor (1950). See Remarks. Leptophis aestivus: Bell 1826:329. Herpetodryas aestivus: Schlegel1837: 15 1. Herpetodryas aesti- vus is a composite name that included not only Herpetodryas Opheodrys aestivus from (Opheodtys) aestivus, but also Philodryas aestivus Dumkril, White County, Arkansas (photograph by M.V.-- Plummer). Bibron, and DumCril 1854, of southern South America. DumCril et al. (1854) separated the two species and, confus. ingly, used the same eipthet to name the South American spe. cies (Kraig Adler, pers. comm.). Leptophis majalis Baird and Girard 1853a: 107. Type locality, "Indianola and New Braunfels, Texas, and Red River." Ho- lotype, National Museum of Natural History (USNM) 1436, female, collected by J.D. Graham, date of collection unknown (not examined by authors). Grobman (1984) restricted the type locality to New Braunfels, Comal County, Texas. See Remarks. Opheodrys aestivus: Cope 1860:560. First use of combination. Cyclophis aestivus: Cope 1875:38. Phyllophilophis aestivus: Garman 1892:283. Phillophilophis aestivus: Hurter 1893:256. Contia aestivus: Boulenger 1894:258. FIGURE 2. Adult 0pheodry.s aestivus from White County, Arkansas Opheodrys aestivas: Gates 1929:555. (photograph by M.V. Plummer). Opheodrys aestivus aestivus: Grobman 1984: 160. Type local- ity, "one mile west of Parkville, McCormick County, South Carolina." Neotype, United States National Museum (USNM) ally I + 2. -

Sharp-Tailed Snake

H WILDLIFE IN BRITIS COLUMBIAAT RISK Sharp-tailed Snake This slug-eating snake is Endangered and is found at only a handful of sites in coastal British Columbia. Ministry of Water, Land & Air Protection Other threats to the Sharp-tailed most likely an error. Recent records Snake include loss of critical habitats (since 1996) come from North Pender, or cover because of landscaping prac- South Pender, and Saltspring islands and tices or recreational activities. Snakes from the district of Metchosin. Addit- Why are Sharp-tailed Snakes may also be run over by vehicles, ional undiscovered populations may at risk? or be killed by domestic cats or other exist along the coast, but it is unlikely he Sharp-tailed Snake has a very re- predators. that there are many of these. At each of stricted geographic range in Canada the known sites, the area occupied by and is found in only a few localities in What is their status? these snakes appears to be very small Tsouthwestern British Columbia: he Sharp-tailed Snake exists at the (patches less than 3 kilometres long; in the Gulf Islands (North and South northern limits of its distribution in and areas less than a hectare in some Pender, Saltspring, and Galiano) and British Columbia, and its rarity in localities). Populations in British Col- on southern Vancouver Island. Because Tthe province is probably due to his- umbia are probably small, but there these populations are small and isolated, torical factors, such as past climatic fluc- is little information on their densi- they are vulnerable to extinction from tuations. -

Appendix F Bibliography

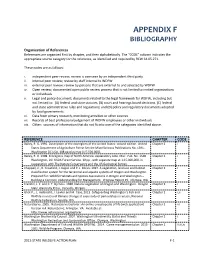

APPENDIX F BIBLIOGRAPHY Organization of References References are organized first by chapter, and then alphabetically. The “CODE” column indicates the appropriate source category for the reference, as identified and required by RCW 34.05.271. These codes are as follows: i. independent peer review; review is overseen by an independent third party ii. internal peer review; review by staff internal to WDFW iii. external peer review; review by persons that are external to and selected by WDFW iv. Open review; documented open public review process that is not limited to invited organizations or individuals v. Legal and policy document; documents related to the legal framework for WDFW, including but not limited to: (A) federal and state statutes, (B) court and hearings board decisions, (C) federal and state administrative rules and regulations; and (D) policy and regulatory documents adopted by local governments. vi. Data from pimary research, monitoring activities or other sources. vii. Records of best professional judgement of WDFW employees or other inidividuals viii. Other: sources of information that do not fit into one of the categories identified above. REFERENCE CHAPTER CODE Bailey, R. G. 1995. Description of the ecoregions of the United States: second edition. United Chapter 2 i States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Miscellaneous Publications No. 1391, Washington DC USA. 108 pp plus map (1:7,500,000). Bailey, R. G. 1998. Ecoregions map of North America: explanatory note. Misc. Pub. No. 1548. Chapter 2 i Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service. 10 pp., with separate map at 1:15,000,000, in cooperation with The Nature Conservancy and the US Geological Survey. -

COLUBRIDAE CONTIA, C. TENUIS Contia Girard

677.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: COLUBRIDAE CONTIA,C. TENUIS Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. -- Leonard, W.P. and K. Ovaska. 1998. Contiu, C. tenuis. Contia Girard Calarnaria H. Boie in F. Boie 1827:519. Type species, Cala- maria lumbricoidea Boie by subsequent designation. Homalosoma Wagler 1830: 190. Considered a substitute name for Duberria Fitzinger. Williams and Wallace (1989) raised the possibility that Homalosonza had been proposed as a new genus, in which case Coluber arctivenrris is the type species. Contia Girard in Baird and Girard 1853: 110. Type species, Contia rnitis (= Calamaria tenuis Baird and Girard) by origi- nal designation and monotypy. hdia Girard in Baird and Girard 1853:116 (= Contia). Type species, Calamarin tenuis by original designation and mono- tYPY. Ablabes DumCril, Bibron, and DumCril 1854:304 (= Lycodono- morphus). Type species, Lycodonornorphus rufulus Fitzinger (= Coronella rufula Lichtenstein) by subsequent designation. CONTENT. Only one monotypic species, Contia tmuis, is recognized. DEFINITION and DIAGNOSIS. Conria is a small, slender snake, TLof adults about 2W0 cm. The small head is dorsally flattened and the snout is rounded. The eyes have a round pu- pil. A slight constriction at the neck separates the head from the body. Dorsal scales are smooth, without pits (see Comments), and in 15 rows. The anal plate (= cloaca1 scute) is divided. Caudals occur as a series of two. The tail is short and tapered, with a sharply pointed scale at the tip. Scalation of the head features 7 each of upper and lower labials, 2 temporals, I pre- and 2 postoculars, 2 nasals that are either entire, divided, or partially divided, I loreal, and paired anterior chin shields that are much larger than those located posteriorly. -

2004 Final SEIS, Volume II

FOREST SERVICE BLM JANUARY 2004 JANUARY Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement To Remove or Modify the Survey and Manage Mitigation Measure Standards and Guidelines Volume II — Appendices Public Lands USA: Use, Share, Appreciate Final SEIS The U.S. Department of Agriculture prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call 202-720-5694 (voice or TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interest of all our people. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in Island Territories under U.S.