An End to Illusions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

The Speaker of the House of Commons: the Office and Its Holders Since 1945

The Speaker of the House of Commons: The Office and Its Holders since 1945 Matthew William Laban Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I, Matthew William Laban, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of this thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: Details of collaboration and publications: Laban, Matthew, Mr Speaker: The Office and the Individuals since 1945, (London, 2013). 2 ABSTRACT The post-war period has witnessed the Speakership of the House of Commons evolving from an important internal parliamentary office into one of the most recognised public roles in British political life. This historic office has not, however, been examined in any detail since Philip Laundy’s seminal work entitled The Office of Speaker published in 1964. -

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997 Parliamentary Information List Standard Note: SN/PC/04657 Last updated: 11 March 2008 Author: Department of Information Services All efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of this data. Nevertheless the complexity of Ministerial appointments, changes in the machinery of government and the very large number of Ministerial changes between 1979 and 1997 mean that there may be some omissions from this list. Where an individual was a Minister at the time of the May 1997 general election the end of his/her term of office has been given as 2 May. Finally, where possible the exact dates of service have been given although when this information was unavailable only the month is given. The Parliamentary Information List series covers various topics relating to Parliament; they include Bills, Committees, Constitution, Debates, Divisions, The House of Commons, Parliament and procedure. Also available: Research papers – impartial briefings on major bills and other topics of public and parliamentary concern, available as printed documents and on the Intranet and Internet. Standard notes – a selection of less formal briefings, often produced in response to frequently asked questions, are accessible via the Internet. Guides to Parliament – The House of Commons Information Office answers enquiries on the work, history and membership of the House of Commons. It also produces a range of publications about the House which are available for free in hard copy on request Education web site – a web site for children and schools with information and activities about Parliament. Any comments or corrections to the lists would be gratefully received and should be sent to: Parliamentary Information Lists Editor, Parliament & Constitution Centre, House of Commons, London SW1A OAA. -

Transcript of Interview with David Kynaston (Historian)

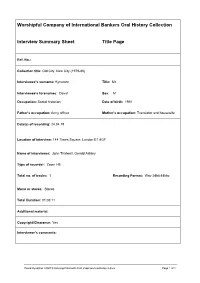

Worshipful Company of International Bankers Oral History Collection Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref. No.: Collection title: Old City, New City (1979-86) Interviewee’s surname: Kynaston Title: Mr Interviewee’s forenames: David Sex: M Occupation: Social historian Date of birth: 1951 Father’s occupation: Army officer Mother’s occupation: Translator and housewife Date(s) of recording: 24.04.19 Location of interview: 144 Times Square, London E1 8GF Name of interviewer: John Thirlwell, Gerald Ashley Type of recorder: Zoom H5 Total no. of tracks: 1 Recording Format: Wav 24bit 48khz Mono or stereo: Stereo Total Duration: 01:03:11 Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Yes Interviewer’s comments: David Kynaston 240419 transcript final with front sheet and endnotes-3.docx Page 1 of 1 Introduction and biography #00:00:00# A club no more: changes from the pre-1980’s village; the #00:0##### aluminium war; Lord Cobbold #00:07:36# Factors of change and external pressures; effects of the abolition of Exchange Control; minimum commissions and single and dual capacity The Stock Exchange ownership question; opening ip to #00:12:17# foreign competition; silly prices paid for firms Cazenove & Co – John Kemp-Welch on partnership and #00:14:57# trust; US capital; Cazenove capital raising Motivations of Big Bang; Philips & Drew; John Craven and #00:18:22# ‘top dollar’ Lloyd’s of London #00:22:26# Bank of England; Margaret Thatcher’s view of the City and #00:25:07# vice versa and her relationship with the Governor, Lord Cobbold Robin Leigh-Pemberton -

Ideology and Cabinet Selection Under Margaret Thatcher 1979-1990

Prime Ministerial Powers of Patronage: Ideology and Cabinet Selection under Margaret Thatcher 1979-1990 Abstract: This article will examine how Margaret Thatcher utilised the Prime Ministerial power of Cabinet ministerial appointment between 1979 and 1990. The article will utilise the Norton taxonomy on the parliamentary Conservative Party (PCP) to determine the ideological disposition (non-Thatcherite versus Thatcherite) of her Cabinet members across her eleven years in office. It will assess the ideological trends in terms of appointments, promotions and departures from Cabinet and it will use archival evidence to explore the advice given to Thatcher to assist her decision-making. Through this process the article will demonstrate how Thatcher was more ideologically balanced than academics have traditionally acknowledged when discussing her Cabinet selections. Moreover, the article will also demonstrate the significance attached to media presentation skills to her decision-making, thus challenging the emphasis on ideology as a dominant determinant of Cabinet selection. Keywords: Conservative Party; Margaret Thatcher; Thatcher Government 1979-1990; Ministerial Selection; Cabinet Ministers. 1 Introduction: This article contributes to the academic literature on the political leadership of Margaret Thatcher, focusing on the powers of patronage that a Prime Minister possesses in terms of Cabinet selection. The article will address the following three research questions: first, how ideologically balanced were her Cabinets; second, did she demonstrate a bias towards Thatcherites in terms of promotions into Cabinet; and, third, was there a bias towards non- Thatcherites in terms of departures from Cabinet? In answering these questions, the article will use archival evidence to gain insights into the factors shaping her decision-making on Cabinet selection. -

100 Years of Government Communication

AZ McKenna 100 Years of Government Communication AZ McKenna John Buchan, the frst Director of Information appointed in 1917 Front cover: A press conference at the Ministry of Information, 1944 For my parents and grandparents © Crown copyright 2018 Tis publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identifed any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. 100 YEARS OF GOVERNMENT COMMUNICATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must frstly record my thanks to Alex Aiken, Executive Director of Government Communication, who commissioned me to write this book. His interest in it throughout its development continues to fatter me. Likewise I am indebted to the Government Communication Service who have overseen the book’s production, especially Rebecca Trelfall and Amelie Gericke. Te latter has been a model of eficiency and patience when it has come to arranging meetings, ordering materials and reading every draft and redraft of the text over the last few months. I am also grateful for the efforts of Gabriel Milland – lately of the GCS – that laid much of the groundwork for the volume. However, I would never even have set foot in the Cabinet Ofice had Tom Kelsey of the Historians in Residence programme at King’s College London not put my name forward. I am also hugely grateful to numerous other people at King’s and within the wider University of London. In particular the contemporary historians of the Department of Political Economy – among them my doctoral supervisors Michael Kandiah and Keith Hamilton – and those associated with the International History Seminar of the Institute of Historical Research (IHR) – Michael Dockrill, Matthew Glencross, Kate Utting as well as many others – have been a constant source of advice and encouragement. -

A Century of Premiers: Salisbury to Blair

A Century of Premiers Salisbury to Blair Dick Leonard A Century of Premiers Also by Dick Leonard THE BACKBENCHER AND PARLIAMENT (ed. with Val Herman) CROSLAND AND NEW LABOUR (ed.) THE ECONOMIST GUIDE TO THE EUROPEAN UNION ELECTIONS IN BRITAIN: A Voter’s Guide (with Roger Mortimore) GUIDE TO THE GENERAL ELECTION PAYING FOR PARTY POLITICS THE PRO-EUROPEAN READER (ed. with Mark Leonard) THE SOCIALIST AGENDA: Crosland’s Legacy (ed. with David Lipsey) WORLD ATLAS OF ELECTIONS (with Richard Natkiel) A Century of Premiers Salisbury to Blair Dick Leonard © Dick Leonard 2005 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2005 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. -

Metaphors in the Educational Narratives Since 1945 with Particular Reference to the Conservative Party

Metaphors in the Educational Narratives since 1945 with particular reference to the Conservative Party being a thesis submitted by John J. McAllister for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Glasgow Department of Education: Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow June 1999 ProQuest Number: 13815571 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13815571 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ( Summary: 1 Summary Metaphors in the Educational Narratives since 1945 with particular reference to the Conservative Party This study seeks to provide both a methodology and an application of that methodology in its account, partly historical, partly philosophical, of the metaphors in the educational narratives since 1945. It considers, in particular, selected texts of the Conservative Party and focusses on the paradigm shifts in the educational narratives in 1945 and again in 1979. The study deconstructs these narratives, teasing out their constitutive metaphors: their characteristic representations of educational identities, realities and relationships. The ideological subtexts of these representations are described, as is the process by which they came to represent the ‘common sense’ of education as the metaphors which constituted them became literalised. -

Margaret Thatcher's Cabinet

Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet “If you want something said, ask a man; if you want something done, ask a woman.” —Margaret Thatcher Dear Delegates, Welcome to WUMUNS 2018! My name is Stephen Bertelsman, and I am your director for Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet. I am in the class of 2019 at Washington University in St. Louis, majoring in Political Science and History. In addition to directing this committee, I serve as the president of our Model United Nations team. I have been involved in Washington University’s Model UN organization since my first year and consider my teammates my closest friends. As a native of St. Louis, I cannot wait to welcome you to our city for an exciting weekend. Our committee will begin on May 4, 1979, when Queen Elizabeth II invited Margaret Thatcher to form a government. Thatcher, dubbed “the Iron Lady” by the Soviet press, charged ahead, ready to tackle the daunting issues of the day. But Thatcher, formidable as she may be, cannot lead the whole nation alone. She needs the help of you, her loyal cabinet, to effectively govern the nation. Will you rise to the occasion? Or will you stand idly by as the greatest empire in the world crumbles away? The decisions are yours alone to make. Dare to be bold, but remember the old adage: “The higher up the mountain, the more treacherous the fall.” If you have any questions while preparing for the conference, please do not hesitate to contact me at [email protected]. God Save the Queen! Sincerely yours, Stephen Bertelsman Contents Committee Mandate……………….…………..……………………… 1 Background Information..……………………………...…………. -

The London Gazette, 23Rd June 1987 8003

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 23RD JUNE 1987 8003 350. South Norfolk County Constituency 381. Nottingham South Borough Constituency The Right Honourable John Roddick Russell MACGREGOR, Martin Maurice BRANDON-BRAvo, Esquire. O.B.E. 351. South West Norfolk County Constituency OXFORDSHIRE Gillian Patricia Mrs. SHEPHARU. 382. Banbury County Constituency 352. Norwich North Borough Constituency Antony Brian BALDRY, Esquire. Hugh Patrick THOMPSON, Esquire. 383. Henley County Constituency 353. Norwich South Borough Constituency The Right Honourable Michael Ray Dibdin HESELTINE. John Laurence GARRETT, Esquire. 384. Oxford West and Abingdon County Constituency John Haggitt Charles PATTEN, Esquire. NORTH YORKSHIRE 385. Wantage County Constituency 354. Harrogate County Constituency Robert Victor JACKSON, Esquire. Robert George BANKS, Esquire. 386. Witney County Constituency 355. Richmond (Yorks) County Constituency The Right Honourable Douglas Richard HURD, C.B.E. The Right Honourable Leon BRITTAN, Q.C. 387. Oxford East Borough Constituency 356. Ryedale County Constituency Andrew David SMITH, Esquire. John Robert GREENWAY, Esquire. 357. Scarborough County Constituency SHROPSHIRE Sir Michael Norman SHAW, Knight. 388. Ludlow County Constituency 358. Selby County Constituency Christopher John Fred GILL, Esquire, R.D. The Right Honourable Michael James Hugh ALISON. 389. North Shropshire County Constituency 359. Skipton and Ripon County Constituency The Right Honourable William John BIFFEN. David Maurice CURRY, Esquire. 390. Shrewsbury and Atcham County Constituency 360. York Borough Constituency Derek Leslie CONWAY, Esquire. Conal Robert GREGORY, Esquire. 391. The Wrekin Borough Constituency NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Bruce GROCOTT, Esquire. 361. Corby County Constituency SOMERSET William Rhys POWELL, Esquire. 392. Bridgwater County Constituency 362. Daventry County Constituency The Right Honourable Thomas Jeremy KING. Timothy Eric BOSWELL, Esquire. 393. -

Original File Was 2Ndsubmission.Tex

THE FURTHER RISE OF THE CAREER POLITICIAN Soeren J. Henn† Abstract Political careers have changed dramatically in the last fifty years. Still, political science research has yet to fully quantify this development. Building on existing literature on career politicians, this study uses a handful of indicators introduced by King (1981), a new variable (pre-parliamentary occupations), and an original data set compiled by the author. The paper’s contribution to the literature is threefold. Firstly, using the variables introduced by King, I observe that a plateau in the number of career politicians has been reached. Secondly, when looking at the occupational background of politicians, the data show a further rise in career politicians. Thirdly, this development is especially prevalent among cabinet ministers. Keywords: British Politics, Political Careers, Political Recruitment † Harvard University, [email protected]. I am very grateful to Anthony King for excellent advice and support. I also thank Pippa Norris, Jonathan Homola, Priya Shanmugam and participants of the European Political Science Association conference for helpful comments and suggestions. 1 Introduction Political careers have changed dramatically in the last fifty years. Political science has tried to keep up with this development by looking at the professionalization of politics (Squire, 1992, 1993, 2007), the convergence of political careers across countries (Best and Cotta, 2000), the representation of women and minorities (Lovenduski and Norris, 1994; Norris, 1997; Dunrose et al, 2013; Allen and Cutts, 2016; Homola, Forthcoming), and pre-parliamentary professions (Allen, 2012; Cairney, 2012; Goplerud, 2015; Cairney et al, 2016). Recent work on party leaders (Cowley, 2012; Barber, 2014) shows a changing landscape at the top of politics. -

Thatcher Papers

Thatcher Papers Catalogue of material open for research (March 2004) Andrew Riley Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge 2. © Churchill Archives Centre, 2004 Version 1:2 (18.3.04 – AR/CRC) Font: Adobe Minion Pro Thatcher Papers: catalogue of material open for research 3. Overview Digitalised material indicated in red (available for purchase on CD-ROM). pp5-48 Pre-1979 personal papers (THCR 1) [all filmed] 49-50 Correspondence with Howe, Joseph and Lawson, 1975-9 (THCR 2/1) [all filmed] 51-130 Political subject files, 1975-9 [279 folders] (THCR 2/6/1) [partly filmed] 131-52 General election material, 1979 (THCR 2/7/1) [partly filmed] 153-58 Economic briefings, [1962]-79 (THCR 2/12) [all filmed] 159-64 Engagement diaries, 1962-78 (THCR 6/1/1) [partly filmed] 165-70 Papers relating to visit to USA and Canada in September 1975 (THCR 6/4/1) [partly filmed] 171-76 Press cuttings, 1949-80 (THCR 7/1) 177-91 Appendix: Thatcher Digital Archive [stored on CD-ROM; available for copying on CD-ROM] Technical specifications of filming programme by Margaret Thatcher Foundation & copy prices (1) List of Thatcher Papers available on CD-ROM Thatcher Papers: catalogue of material open for research 4. (THCR AS 10/1) (2) List of documents from other collections available on CD-ROM (eg, Reagan Library) (THCR AS 10/2) (3) Archived material from margaretthatcher.org, the official website of the Margaret Thatcher Foundation (THCR AS 10/3) Certain items remain closed at present as they contain copies of official papers supplied to Margaret Thatcher in Opposition or on data protection grounds.