Requisites of Englightenment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meditation, Modern Buddhism, and the Burmese Monk Ledi Sayadaw

Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics Volume 22, 2015 The Birth of Insight: Meditation, Modern Buddhism, and the Burmese Monk Ledi Sayadaw Reviewed by Douglas Ober University of British Columbia [email protected] Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. All enquiries to: [email protected] A Review of: The Birth of Insight: Meditation, Modern Buddhism, and the Burmese Monk Ledi Sayadaw Douglas Ober 1 The Birth of Insight: meditation, modern Buddhism, and the Burmese monk Ledi Sayadaw. By Erik Braun. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013, xvi + 257, ISBN 13: 978-0-226- 00080-0 (cloth), US $45.00, ISBN 13: 978-0-226-00094-7 (e-book), US $7.00 to $36.00. In a pavilion just outside the Shwedagon Temple in Burma stands a large map marking more than 100 vipassanā centers around the globe. As the map indicates, meditation has become a global phenomenon. But “mass meditation,” Erik Braun writes in The Birth of Insight, “was born in Burma only in the early years of the nineteenth century and at a scale never seen before in Buddhist history” (3). Understanding why the movement began “then and there” is the sine qua non of this recent addition to the excellent “Buddhism and Modernity” series published by the University of Chicago Press. -

Book (2) (All) Guide to Life Maýgalà Literature Class Second and Third Grade Maýgalà Examination

Guide to life: Maýgala Literature Class Second and Third Grade Maýgala Examination CONTENTS 1. Author’s preface ------------------------------------------------- 2 2. Maýgalà is the guide of life ------------------------------------ 4 3. Maýgalà in Pàli and poetry -------------------------------------- 6 4. Maýgalà examples for second and third level--------------- 8 5. The nature and guideline of 38 Maýgalas ----------------- 26 6. Primary Mangala model essays ------------------------------- 36 7. Model essays for middle and higher forms --------------- 37 8. Extracts from "Introduction To Maýgalà" ------------------- 43 9. Selections of 38 Maýgalas explanations ---------------------- 47 10. Serial numbers of the Maýgalà ------------------------------ 109 11. Analysis of Maýgalà -------------------------------------------- 110 12. The presented text method of examination of Maýgala ---- 114 13. Old questions for second grade examination --------------- 131 14. Old third grade questions ------------------------------------ 136 15. Answers to the second grade old questions -------------- 141 16. Third great old questions and answers --------------------- 152 17. The lllustrated history of Buddha --------------------------- 206 18. Proverbs to write essays ------------------------------------- 231 19. Great abilities of Maýgalà ------------------------------------ 234 Book (2) (all) Guide To Life Maýgalà literature class Second and Third Grade Maýgalà Examination Written by Lay-Ein-Su Ashin Vicittasàra Translated by U Han Htay, B.A Advisor, -

Buddhism Illuminated: Manuscript Art from Southeast Asia London: the British Library, 2018

doi: 10.14456/jms.2018.27 ISBN 978 0 7123 5206 2. Book Review: San San May and Jana Igunma. Buddhism Illuminated: Manuscript Art from Southeast Asia London: The British Library, 2018. 272 pages. Bonnie Pacala Brereton Email: [email protected] This stunning book is superb in every way. Immediately obvious is the quality of the photographs of the British Library’s extensive collections; equally remarkable is the amount of information about the objects in the collections and how they relate to local histories, teachings, sacred sites and legends. Then there is the writing — clear and succinct, free from academic jargon and egoistic agendas. The authors state in the preface that through this book they wished to honor Dr. Henry Ginsburg, who worked for the British Library for 30 years, building up one of the finest collections of Thai illustrated manuscripts in the world before his untimely death in 2007. Dr. Ginsburg would surely be delighted at this magnificent way of paying tribute. The authors, San San May and Jana Ignunma, hold curatorial positions at the British Library, and thus are in close contact with the material they write about. In organizing a book that aims to highlight items in a museum’s or library’s collection, authors are faced with many choices. Should it be organized by date, theme, medium, provenance etc.? Here they have chosen to examine the items in terms of their relationship to the essential aspects of Theravada Buddhism as practiced in mainland Southeast Asia: the components of the Three Gems (the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha) and the concepts of Kamma (cause and effect) and Punna (merit). -

Primary Point, Vol 21 Num 1

our school in the broader context of Korean Buddhist activity in southern California-did you know that there's BrieF Reviews a temple in Los Angeles not in our school known as Kwan Urn Sa? The two longest profiles are ofSarnu Sunim, based judy Reitman jDPSN in Toronto and teaching mostly European-Canadians/ Americans through his Zen Lotus Sociery; and of Zen Butterflies On A Sea Wind: Master Seung Sahn, giving a slightly different version than Beginning Zen by Anne Rudloe, the canonical one most of us have heard. More interesting published by Andrews McNeel, is Samu Sunim's very generous article Turning the Wheel of Kansas Ciry, 2002 Dharma in the West, which has an excellent synopsis of Anne Rudloe is the abbot of the the history of Buddhism in Korea, and then profiles three Cypress Tree Zen Group in teachers: Ven. Dr. Seo, Kyung-Bo, a charismatic teacher Tallahassee, Florida. This book is who towards the end ofhis life became the self-proclaimed I basically a description of what it's world dharma-raja; Kusan Sunim, one of only two (the like to be a relative beginner in Zen other is Zen Master Seung Sahn) Korean teachers who practice, both on and off the went out of their way to encourage western students to cushion. Rudloe brings together three strands of her life: study in Korean monasteries; and Zen Master Seung Sahn. her experience practicing Zen (especially on retreats); her Samu Sunim also gives an extensive history and description personallife-farnily, work, and ecological activism; and of our school, and responds directly to charges made the natural world around her. -

Lineage: Beginnings

Soto Zen Buddhism in Australia March 2018, Issue 71 LINEAGE: BEGINNINGS ABBOT’S NEWS I CANNOT STEP ON REMEMBERING RAISING A WALL INDIA STUDY ABROAD Hannah Forsyth THEIR SHADOW NARASAKI ROSHI Katherine Yeo & Karen Sunao Ekin Korematsu & Seido Suzuki Roshi Nonin Chowaney Threlfall Jake Kepper BUDDHA'S BOUNDLESS RETURNING HOME, DIRECT REALISATION BACK TO THE FUTURE SOTO KITCHEN COMPASSION SITTING PEACEFULLY HUT John Hickey Karen Threlfall Ikko Narasaki Roshi Ekai Korematsu Osho Deniz Yener Korematsu MYOJU IS A PUBLICATION OF JIKISHOAN ZEN BUDDHIST COMMUNITY INC Editorial Myoju “Even though the ways of ceaseless practice by our founding Editor: Ekai Korematsu Osho Ancestors are many, I have given you this one for the present.” Editorial Committee: Hannah Forsyth, Shona Innes, Robin Laurie, Jessica Cummins —Dogen Zenji, Shobogenzo Gyoji: On Ceaseless Practice Myoju Coordinator: Jessica Cummins Production: Dan Carter Website Manager: Lee-Anne Armitage As Jikishoan approaches its 20th anniversary in 2019, IBS Teaching Schedule: Hannah Forsyth this year Myoju will explore our identity as a community Jikishoan Calendar of Events: Shona Innes through the theme of Lineage. As a young, lay communi- Contributors: Ikko Narasaki Roshi, Seido Suzuki Roshi, ty, practising in a spiritual tradition that originates far be- Ekai Korematsu Osho, Shudo Hannah Forsyth, Shona yond our land and culture, we do not do so in isolation. Innes, Nonin Chowaney, Deniz Yener Korematsu, 78 generations of the Soto Zen Buddhist tradition are em- Katherine Yeo, Karen Threlfall, John Hickey, Sunao Ekin bodied in the forms of our practice and training, allowing Korematsu, Jake Kepper. us to experience an inclusivity and belonging that takes us Cover Image: Ikko Narasaki Roshi beyond our individual practice. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Excerpts for Distribution

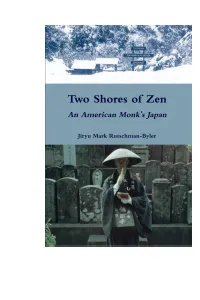

EXCERPTS FOR DISTRIBUTION Two Shores of Zen An American Monk’s Japan _____________________________ Jiryu Mark Rutschman-Byler Order the book at WWW.LULU.COM/SHORESOFZEN Join the conversation at WWW.SHORESOFZEN.COM NO ZEN IN THE WEST When a young American Buddhist monk can no longer bear the pop-psychology, sexual intrigue, and free-flowing peanut butter that he insists pollute his spiritual community, he sets out for Japan on an archetypal journey to find “True Zen,” a magical elixir to relieve all suffering. Arriving at an austere Japanese monastery and meeting a fierce old Zen Master, he feels confirmed in his suspicion that the Western Buddhist approach is a spineless imitation of authentic spiritual effort. However, over the course of a year and a half of bitter initiations, relentless meditation and labor, intense cold, brutal discipline, insanity, overwhelming lust, and false breakthroughs, he grows disenchanted with the Asian model as well. Finally completing the classic journey of the seeker who travels far to discover the home he has left, he returns to the U.S. with a more mature appreciation of Western Buddhism and a new confidence in his life as it is. Two Shores of Zen weaves together scenes from Japanese and American Zen to offer a timely, compelling contribution to the ongoing conversation about Western Buddhism’s stark departures from Asian traditions. How far has Western Buddhism come from its roots, or indeed how far has it fallen? JIRYU MARK RUTSCHMAN-BYLER is a Soto Zen priest in the lineage of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. He has lived in Buddhist temples and monasteries in the U.S. -

Xvii Three Baskets (Tipitaka) I Buddhism

261 XVII THREE BASKETS ( TIPITAKA ) I BUDDHISM COTETS 1. What is the Tipitaka ? 2. Language of Buddha’s words (Buddhavacana ) 3. What is Pali? 4. The First Council 5. The Second Council 6. The Great Schism 7. Origin of the Eighteen ikayas (Schools of Buddhism) 8. The Third Council 9. Committing the Tipitaka to Memory 10. Fourth Council: Committing the Tipitaka to Writing 11. Fifth and Sixth Councils in Myanmar 12. Conclusion 13. Appendix: Contents of the Tipitaka or Three Baskets 14. Explanatory Notes 15. References 262 • Buddhism Course 1. What is the Tipitaka ? The word of the Buddha, which is originally called the Dhamma , consists of three aspects, namely: Doctrine ( Pariyatti ), Practice (Patipatti ) and Realization ( Pativedha ). The Doctrine is preserved in the Scriptures called the Tipitaka . English translators of the Tipitaka have estimated it to be eleven times the size of the Christian Bible. It contains the Teachings of the Buddha expounded from the time of His Enlightenment to Parinibbana over forty-five years. Tipitaka in Pali means Three Baskets (Ti = Three, Pitaka = Basket), not in the sense of function of storing but of handing down , just like workers carry earth with the aid of baskets handed on from worker to worker, posted in a long line from point of removal to point of deposit, so the Baskets of Teachings are handed down over the centuries from teacher to pupil. The Three Baskets are: Basket of Discipline ( Vinaya Pitaka ), which deals mainly with the rules and regulations of the Order of monks and nuns; Basket of Discourses ( Sutta Pitaka ) which contains the discourses delivered by the Buddha to individuals or assemblies of different ranks in the course of his ministry; Basket of Ultimate Things ( Abhidhamma Pitaka ) which consists of the four ultimate things: Mind ( Citta ), Mental-factors ( Cetasikas ), Matter ( Rupa ) and ibbana . -

The Paṭṭhāna (Conditional Relations) and Buddhist Meditation: Application of the Teachings in the Paṭṭhāna in Insight (Vipassanā) Meditation Practice

The Paṭṭhāna (Conditional Relations) and Buddhist Meditation: Application of the Teachings in the Paṭṭhāna in Insight (Vipassanā) Meditation Practice Kyaw, Pyi. Phyo SOAS, London This paper will explore relevance and roles of Abhidhamma, Theravāda philosophy, in meditation practices with reference to some modern Burmese meditation traditions. In particular, I shall focus on the highly mathematical Paṭṭhāna, Pahtan in Burmese, the seventh text of the Abhidhamma Piṭaka, which deals with the functioning of causality and is regarded by Burmese as the most important of the Abhidhamma traditions. I shall explore how and to what extent the teachings in the Paṭṭhāna are applied in insight (vipassanā) meditation practices, assessing the roles of theoretical knowledge of ultimate realities (paramattha-dhammā)1 in meditation. In so doing, I shall attempt to bridge the gap between theoretical and practical aspects of Buddhist meditation. While scholars writing on Theravāda meditation - Cousins,2 King3 and Griffiths4 for example - have focused on distinction between insight meditation (vipassanā) and calm meditation (samatha), this paper will be the first to classify approaches within vipassanā meditation. Vipassanā meditation practices in contemporary Myanmar can be classified into two broad categories, namely, the theoretical based practice and the non- theoretical based practice. Some Burmese meditation masters, Mohnyin Sayadaw Ven. U Sumana (1873-1964)5 and Saddhammaransī Sayadaw Ven. Ashin Kuṇḍalābhivaṃsa (1921- ) and Pa-Auk Sayadaw Ven. Āciṇṇa (1934- ) for example, teach meditators to have theoretical knowledge of ultimate realities. While these meditation masters emphasize theoretical knowledge of the ultimate realities, other meditation masters such as the Sunlun Sayadaw Ven. U Kavi (1878-1952) and the Theinngu Sayadaw Ven. -

Bibliography Glossary

366 BIBLIOGRAPHY GLOSSARY -^ f 367 BIBLIOGRAPHY A. Primary Sources Abhidhamma-Mulatlkd [Se], Sinhalese edition, edited by Dehigaspe Pandit Pannasara Thera & Palannoruve Pandit Wimaladhamma Thera, finally revised by Kukulanpe Siri Dewarakkhita Thera, approved by Baddegama Siri Piyaratana Nayaka Thera, and published as Volume VII, Vidyodaya Tika Publication, Colombo, 1938. Abhidhamma-Mulatlkd [Ue], Ramasahkara TripathI, Sampurnananda Sanskrit University, Varanasi, 1988. Abhidhammatthasangaha & Abhidhammatthavibhdviril-tikd [Atths (Ve) & Atth-vt (Ve)], Vol. 133, Devanagari edition of the Pali text of the Chattha Sahgayana, Vipassana Research Institute, Igatpiui, 1998. Ahguttara-Nikdya [AN] 5 Vols, edited by R. Morris & E. Hardy, The Pali Text Society, London, 1961-1976. Ahguttaranikdya-Tikd [AN-t (Ve)], Vol. 44-46, Devanagari edition of the Pali text of the Chattha Sahgayana, Vipassana Research Institute, Igatpuri,1995. Anudlpariipdtha [Ad], Myanmar edition of the Pali text of the Chattha Sangayana published by Department of Religious Affairs in Myarraiar. Apaddna [Ap (Ve)], Vol. 57-58, Devanagari edition of the Pali text of the Chattha Sahgayana, Vipassana Research Institute, Igatpuri, 1998. Atthsdlinl: Buddhaghosa's Commentary on the Dhammasahgani edited by P.V. Bapat and R.D. Vadekar, Bhandarkar Oriental Series No. 3, Poona, 1942. Atthasdlini, edited by Ramasahkara TripathI, Sampumanand Sanskrit University, Varanasi, 1989. Atthasdlirii-Atthayojandya, edited by Ramasahkara TripathI, Sampumanand Sanskrit University, Varanasi, 1989. Atthasdinibhdsdtikd [Ab-t], Vol. II, written by Ven. Janakabhivamsa, New Burma offset Pitaka Publication, Amarapura, 4"' edition 2002. Atthasdinibhdsdtikd [Ab-t], Vol. Ill, by Ven. Janakabhivamsa, New Burma offset Pitaka Publication, Amarapura, 4* edition 1995 (Myanmar Script). Culaniddesa [Cnd (Ve)], Vol. 78, Devanagari edition of the Pali text of the Chattha Sahgayana, Vipassana Research Institute, Igatpuri, 1998. -

The Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Persinger, Allan, "Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 748. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/748 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Kimberly M. Blaeser My dissertation is a creative translation from Japanese into English of the poetry of Yosa Buson, an 18th century (1716 – 1783) poet. Buson is considered to be one of the most important of the Edo Era poets and is still influential in modern Japanese literature. By taking account of Japanese culture, identity and aesthetics the dissertation project bridges the gap between American and Japanese poetics, while at the same time revealing the complexity of thought in Buson's poetry and bringing the target audience closer to the text of a powerful and mov- ing writer. -

Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience*

BUDDHIST MODERNISM AND THE RHETORIC OF MEDITATIVE EXPERIENCE* ROBERT H. SHARF What we can 't say we can't say and we can't whistle either. Frank Ramsey Summary The category "experience" has played a cardinal role in modern studies of Bud- dhism. Few scholars seem to question the notion that Buddhist monastic practice, particularly meditation, is intended first and foremost to inculcate specific religious or "mystical" experiences in the minds of practitioners. Accordingly, a wide variety of Buddhist technical terms pertaining to the "stages on the path" are subject to a phenomenological hermeneutic-they are interpreted as if they designated discrete "states of consciousness" experienced by historical individuals in the course of their meditative practice. This paper argues that the role of experience in the history of Buddhism has been greatly exaggerated in contemporary scholarship. Both historical and ethnographic evidence suggests that the privileging of experience may well be traced to certain twentieth-century Asian reform movements, notably those that urge a "return" to zazen or vipassana meditation, and these reforms were pro- foundly influenced by religious developments in the West. Even in the case of those contemporary Buddhist schools that do unambiguously exalt meditative experience, ethnographic data belies the notion that the rhetoric of meditative states functions ostensively. While some adepts may indeed experience "altered states" in the course of their training, critical analysis shows that such states do not constitute the reference points for the elaborate Buddhist discourse pertaining to the "path." Rather, such discourse turns out to function ideologically and performatively-wielded more often than not in the interests of legitimation and institutional authority.