The Kettle Creek Battlefield Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 3 No. 1.1 ______January 2006

Vol. 3 No. 1.1 _____ ________________________________ _ __ January 2006 th Return to the Cow Pens! 225 Backyard Archaeology – ARCHH Up! The Archaeological Reconnaissance and Computerization of Hobkirk’s Hill (ARCHH) project has begun initial field operations on this built-over, urban battlefield in Camden, South Carolina. We are using the professional-amateur cooperative archaeology model, loosely based upon the successful BRAVO organization of New Jersey. We have identified an initial survey area and will only test properties within this initial survey area until we demonstrate artifact recoveries to any boundary. Metal detectorist director John Allison believes that this is at least two years' work. Since the battlefield is in well-landscaped yards and there are dozens of homeowners, we are only surveying areas with landowner permission and we will not be able to cover 100% of the land in the survey area. We have a neighborhood meeting planned to explain the archaeological survey project to the landowners. SCAR will provide project handouts and offer a walking battlefield tour for William T. Ranney’s masterpiece, painted in 1845, showing Hobkirk Hill neighbors and anyone else who wants to attend on the final cavalry hand-to-hand combat at Cowpens, hangs Sunday, January 29, 2006 at 3 pm. [Continued on p. 17.] in the South Carolina State House lobby. Most modern living historians believe that Ranney depicted the uniforms quite inaccurately. Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion cavalry is thought to have been clothed in green tunics and Lt. Col. William Washington’s cavalry in white. The story of Washington’s trumpeter or waiter [Ball, Collin, Collins] shooting a legionnaire just in time as Washington’s sword broke is also not well substantiated or that he was a black youth as depicted. -

R2361 William Couch

Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters Pension application of William Couch R2361 f16SC Transcribed by Will Graves 7/17/06 rev'd 6/4/11 & 8/19/14 [Methodology: Spelling, punctuation and/or grammar have been corrected in some instances for ease of reading and to facilitate searches of the database. Where the meaning is not compromised by adhering to the spelling, punctuation or grammar, no change has been made. Corrections or additional notes have been inserted within brackets or footnotes. Blanks appearing in the transcripts reflect blanks in the original. A bracketed question mark indicates that the word or words preceding it represent(s) a guess by me. The word 'illegible' or 'indecipherable' appearing in brackets indicates that at the time I made the transcription, I was unable to decipher the word or phrase in question. Only materials pertinent to the military service of the veteran and to contemporary events have been transcribed. Affidavits that provide additional information on these events are included and genealogical information is abstracted, while standard, 'boilerplate' affidavits and attestations related solely to the application, and later nineteenth and twentieth century research requests for information have been omitted. I use speech recognition software to make all my transcriptions. Such software misinterprets my southern accent with unfortunate regularity and my poor proofreading skills fail to catch all misinterpretations. Also, dates or numbers which the software treats as numerals rather -

Battle of the Shallow Ford

Bethabara Chapter of Winston-Salem North Carolina State Society Sons of the American Revolution The Bethabara Bugler Volume 1, Issue 22 November 1, 2020 Chartered 29 October 1994 Re-Organized 08 November 2014. The Bethabara Bugler is the Newsletter of the Bethabara Chapter of Winston-Salem. It is, under normal circumstances, published monthly (except during the months of June, July, and August when there will only be one summer edition). It will be distributed by email, usually at the first of the month. Articles, suggestions, and ideas are welcome – please send them to: Allen Mollere, 3721 Stancliff Road, Clemmons, NC 27012, or email: [email protected]. ----------------------------------------- Bethabara Chapter Meetings As you are aware, no Bethabara Chapter SAR on-site meetings have been held recently due to continuing concerns over the Corona virus. On September 10, 2020, the Bethabara Chapter did conduct a membership meeting via Zoom. ----------------------------------------- Page 1 of 19 Commemoration of Battle of the Shallow Ford Forty-seven individuals wearing protective masks due to the Covid-19 pandemic, braved the inclement weather on Saturday, October 10, 2020 to take part in a modified 240th Commemoration Ceremony of the Battle of the Shallow Ford at historic Huntsville UM Church. Hosted by the Winston-Salem Bethabara Chapter of the Sons of The American Revolution (SAR), attendees included visitors, Compatriots from the Alamance Battleground, Bethabara, Nathanael Greene, Catawba Valley, and Yadkin Valley SAR Chapters as well as Daughters of The American Revolution (DAR) attendees from the Battle of Shallow Ford, Jonathan Hunt, Leonard's Creek, Colonel Joseph Winston, and Old North State Chapters. -

South Carolina Loyalists in the American Revolution South Carolina in 1776 (Adapted by R

South Carolina Loyalists in the American Revolution South Carolina in 1776 (adapted by R. S. Lambert from James Cook, 1773) Note: Broken lines, combined with natural features (e.g. rivers) delineate boundaries of judicial districts. Robert Stansbury Lambert Second Edition Works produced at Clemson University by the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, including Th e South Carolina Review and its themed series “Virginia Woolf International,” “Ireland in the Arts and Humanities,” and “James Dickey Revisited” may be found at our Web site: http://www.clemson.edu/caah/cedp. Contact the director at 864-656-5399 for information. Copyright 2010 by Clemson University ISBN 978-0-9842598-8-5 Second Edition CLEMSON UNIVERSITY DIGITAL PRESS Published by Clemson University Digital Press at the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina. Editorial Assistants: Christina Cook, Ashley Dannelly, Steve Johnson, Carrie Kolb Cover Design: Christina Cook Produced with the Adobe Creative Suite CS5 and Microsoft Word. Th is book is set in Adobe Garamond Pro and was printed by University Printing Services, Offi ce of Publica- tions and Promotional Services, Clemson University. To order copies, contact the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, Strode Tower, Box 340522, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634-0522. To Edythe and Anne Contents Preface .......................................................................................................... viii Abbreviations and Acronyms ....................................................................... -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

Study Guide for the Georgia History Exemption Exam Below Are 99 Entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (Available At

Study guide for the Georgia History exemption exam Below are 99 entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (available at www.georgiaencyclopedia.org. Students who become familiar with these entries should be able to pass the Georgia history exam: 1. Georgia History: Overview 2. Mississippian Period: Overview 3. Hernando de Soto in Georgia 4. Spanish Missions 5. James Oglethorpe (1696-1785) 6. Yamacraw Indians 7. Malcontents 8. Tomochichi (ca. 1644-1739) 9. Royal Georgia, 1752-1776 10. Battle of Bloody Marsh 11. James Wright (1716-1785) 12. Salzburgers 13. Rice 14. Revolutionary War in Georgia 15. Button Gwinnett (1735-1777) 16. Lachlan McIntosh (1727-1806) 17. Mary Musgrove (ca. 1700-ca. 1763) 18. Yazoo Land Fraud 19. Major Ridge (ca. 1771-1839) 20. Eli Whitney in Georgia 21. Nancy Hart (ca. 1735-1830) 22. Slavery in Revolutionary Georgia 23. War of 1812 and Georgia 24. Cherokee Removal 25. Gold Rush 26. Cotton 27. William Harris Crawford (1772-1834) 28. John Ross (1790-1866) 29. Wilson Lumpkin (1783-1870) 30. Sequoyah (ca. 1770-ca. 1840) 31. Howell Cobb (1815-1868) 32. Robert Toombs (1810-1885) 33. Alexander Stephens (1812-1883) 34. Crawford Long (1815-1878) 35. William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891) 36. Mark Anthony Cooper (1800-1885) 37. Roswell King (1765-1844) 38. Land Lottery System 39. Cherokee Removal 40. Worcester v. Georgia (1832) 41. Georgia in 1860 42. Georgia and the Sectional Crisis 43. Battle of Kennesaw Mountain 44. Sherman's March to the Sea 45. Deportation of Roswell Mill Women 46. Atlanta Campaign 47. Unionists 48. Joseph E. -

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

Summary of Proposed National Register/Georgia Register Nomination

SUMMARY OF PROPOSED NATIONAL REGISTER/GEORGIA REGISTER NOMINATION 1. Name: Brier Creek Battlefield 2. Location: Approximately one mile south of Old River Road along Brannen Bridge Road, Sylvania vicinity, Screven County, Georgia 3a. Description: Brier Creek Battlefield is located largely within the state of Georgia’s Tuckahoe Wildlife Management Area (WMA) in Screven County. The battlefield is delineated in the Georgia Archaeological Site Files as archaeological Site 9SN254. The National Register historic district boundary comprises 2,686 acres of this site: 2,521.3 acres are owned by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources as part of the Tuckahoe WMA, while 164.7 acres are privately owned by Warsaw Pines and Timberland LLC, in a silviculture area known locally as Chisolm Farm. These two tracts contain thirteen contributing resources and one noncontributing resource, all of which are archaeological sites, clustered in the western half of the district. The battlefield is located on a natural peninsula formed by the confluence of Brier Creek and the Savannah River. The topography is relatively low and flat, and vegetation consists of mature stands of planted loblolly pine trees actively managed for silviculture. Anhydric soils in the peninsula are surrounded by wet, swampy cypress forests which border Brier Creek and the Savannah River. A dirt road loops the peninsula, running southeast from Brannen Bridge Road. The property’s integrity of location and association are evidenced by historic documentation along with the recovery of military artifacts during archaeological studies, while the open pine forest, bordering cypress swamps, and the battlefield’s overall rural character effectively portray integrity of setting and feeling. -

Kettle Creek Battlefield American Revolutionary War National Park Study

Kettle Creek Battlefield American Revolutionary War National Park Study Remarks by N. Walker Chewning Chairman of the Board of the Kettle Creek Battlefield Association April 2, 2019 Good Afternoon! Why does the Kettle Creek Battlefield in Georgia during the American Revolution in 1779 deserve your attention? First: • As soon as most people hear “Georgia” they think of the Civil War. • That was an important conflict, but today we are focusing on the American Revolution: the war that led to the formation of the United States of America… • …and the War that has resulted in all of us being able to meet together- here- today. Second: • There were several American Revolutionary War engagements in the Colony of Georgia during the War for Independence… • … but the Battle of Kettle Creek was the only engagement the Patriots won in Georgia. Third: • The Kettle Creek Battlefield is ALSO A CEMETERY FOR SOLDIERS who died in that battle. • 18 graves have been located by cadaver dogs and verified by ground penetrating radar, archaeological studies of grave sites, and soil analysis. Fourth: • The Kettle Creek Battlefield is a pristine site: After the battle, the area returned to its agricultural roots. No development has been made to the currently-owned 252.5 acres in over 200 years. Fifth: • In 2019, the State of Georgia, the 13th American Colony, has NO American Revolutionary War National Parks. How did the American War for Independence come to Georgia? • The American Revolution began in Massachusetts in 1775. • Despite numerous battles to subdue the American Revolution in the Northern Colonies, by 1777, the war was at a stalemate. -

The SAR Colorguardsman

The SAR Colorguardsman National Society, Sons of the American Revolution Vol. 5 No. 1 April 2016 Patriots Day Inside This Issue Commanders Message Reports from the Field - 11 Societies From the Vice-Commander Waxhaws and Machias Old Survivor of the Revolution Color Guard Commanders James Barham Jr Color Guard Events 2016 The SAR Colorguardsman Page 2 The purpose of this Commander’s Report Magazine is to o the National Color Guard members, my report for the half year starts provide in July 2015. My first act as Color Guard commander was at Point interesting TPleasant WVA. I had great time with the Color Guard from the near articles about the by states. My host for the 3 days was Steve Hart from WVA. Steve is from my Home town in Maryland. My second trip was to South Carolina to Kings Revolutionary War and Mountain. My host there was Mark Anthony we had members from North Car- information olina and South Carolina and from Georgia and Florida we had a great time at regarding the Kings Mountain. Went home for needed rest over 2000 miles on that trip. That activities of your chapter weekend was back in the car to VA and the Tomb of the Unknown. Went home to get with the MD Color Guard for a trip to Yorktown VA for Yorktown Day. and/or state color guards Went back home for events in MD for Nov. and Dec. Back to VA for the Battle of Great Bridge VA. In January I was back to SC for the Battle of Cowpens - again had a good time in SC. -

Henry Clinton Papers, Volume Descriptions

Henry Clinton Papers William L. Clements Library Volume Descriptions The University of Michigan Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-42cli?view=text Major Themes and Events in the Volumes of the Chronological Series of the Henry Clinton papers Volume 1 1736-1763 • Death of George Clinton and distribution of estate • Henry Clinton's property in North America • Clinton's account of his actions in Seven Years War including his wounding at the Battle of Friedberg Volume 2 1764-1766 • Dispersal of George Clinton estate • Mary Dunckerley's account of bearing Thomas Dunckerley, illegitimate child of King George II • Clinton promoted to colonel of 12th Regiment of Foot • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot Volume 3 January 1-July 23, 1767 • Clinton's marriage to Harriet Carter • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton's property in North America Volume 4 August 14, 1767-[1767] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Relations between British and Cherokee Indians • Death of Anne (Carle) Clinton and distribution of her estate Volume 5 January 3, 1768-[1768] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton discusses military tactics • Finances of Mary (Clinton) Willes, sister of Henry Clinton Volume 6 January 3, 1768-[1769] • Birth of Augusta Clinton • Henry Clinton's finances and property in North America Volume 7 January 9, 1770-[1771] • Matters concerning the 12th Regiment of Foot • Inventory of Clinton's possessions • William Henry Clinton born • Inspection of ports Volume 8 January 9, 1772-May -

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

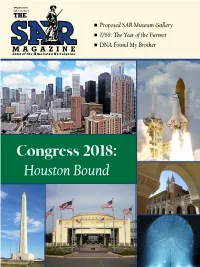

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them.