Roger Heady the Wollemi Pine— 16 Years On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book of Abstracts.Pdf

1 List of presenters A A., Hudson 329 Anil Kumar, Nadesa 189 Panicker A., Kingman 329 Arnautova, Elena 150 Abeli, Thomas 168 Aronson, James 197, 326 Abu Taleb, Tariq 215 ARSLA N, Kadir 363 351Abunnasr, 288 Arvanitis, Pantelis 114 Yaser Agnello, Gaia 268 Aspetakis, Ioannis 114 Aguilar, Rudy 105 Astafieff, Katia 80, 207 Ait Babahmad, 351 Avancini, Ricardo 320 Rachid Al Issaey , 235 Awas, Tesfaye 354, 176 Ghudaina Albrecht , Matthew 326 Ay, Nurhan 78 Allan, Eric 222 Aydınkal, Rasim 31 Murat Allenstein, Pamela 38 Ayenew, Ashenafi 337 Amat De León 233 Azevedo, Carine 204 Arce, Elena An, Miao 286 B B., Von Arx 365 Bétrisey, Sébastien 113 Bang, Miin 160 Birkinshaw, Chris 326 Barblishvili, Tinatin 336 Bizard, Léa 168 Barham, Ellie 179 Bjureke, Kristina 186 Barker, Katharine 220 Blackmore, 325 Stephen Barreiro, Graciela 287 Blanchflower, Paul 94 Barreiro, Graciela 139 Boillat, Cyril 119, 279 Barteau, Benjamin 131 Bonnet, François 67 Bar-Yoseph, Adi 230 Boom, Brian 262, 141 Bauters, Kenneth 118 Boratyński, Adam 113 Bavcon, Jože 111, 110 Bouman, Roderick 15 Beck, Sarah 217 Bouteleau, Serge 287, 139 Beech, Emily 128 Bray, Laurent 350 Beech, Emily 135 Breman, Elinor 168, 170, 280 Bellefroid, Elke 166, 118, 165 Brockington, 342 Samuel Bellet Serrano, 233, 259 Brockington, 341 María Samuel Berg, Christian 168 Burkart, Michael 81 6th Global Botanic Gardens Congress, 26-30 June 2017, Geneva, Switzerland 2 C C., Sousa 329 Chen, Xiaoya 261 Cable, Stuart 312 Cheng, Hyo Cheng 160 Cabral-Oliveira, 204 Cho, YC 49 Joana Callicrate, Taylor 105 Choi, Go Eun 202 Calonje, Michael 105 Christe, Camille 113 Cao, Zhikun 270 Clark, John 105, 251 Carta, Angelino 170 Coddington, 220 Carta Jonathan Caruso, Emily 351 Cole, Chris 24 Casimiro, Pedro 244 Cook, Alexandra 212 Casino, Ana 276, 277, 318 Coombes, Allen 147 Castro, Sílvia 204 Corlett, Richard 86 Catoni, Rosangela 335 Corona Callejas , 274 Norma Edith Cavender, Nicole 84, 139 Correia, Filipe 204 Ceron Carpio , 274 Costa, João 244 Amparo B. -

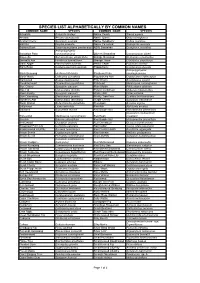

Species List Alphabetically by Common Names

SPECIES LIST ALPHABETICALLY BY COMMON NAMES COMMON NAME SPECIES COMMON NAME SPECIES Actephila Actephila lindleyi Native Peach Trema aspera Ancana Ancana stenopetala Native Quince Guioa semiglauca Austral Cherry Syzygium australe Native Raspberry Rubus rosifolius Ball Nut Floydia praealta Native Tamarind Diploglottis australis Banana Bush Tabernaemontana pandacaqui NSW Sassafras Doryphora sassafras Archontophoenix Bangalow Palm cunninghamiana Oliver's Sassafras Cinnamomum oliveri Bauerella Sarcomelicope simplicifolia Orange Boxwood Denhamia celastroides Bennetts Ash Flindersia bennettiana Orange Thorn Citriobatus pauciflorus Black Apple Planchonella australis Pencil Cedar Polyscias murrayi Black Bean Castanospermum australe Pepperberry Cryptocarya obovata Archontophoenix Black Booyong Heritiera trifoliolata Picabeen Palm cunninghamiana Black Wattle Callicoma serratifolia Pigeonberry Ash Cryptocarya erythroxylon Blackwood Acacia melanoxylon Pink Cherry Austrobuxus swainii Bleeding Heart Omalanthus populifolius Pinkheart Medicosma cunninghamii Blue Cherry Syzygium oleosum Plum Myrtle Pilidiostigma glabrum Blue Fig Elaeocarpus grandis Poison Corkwood Duboisia myoporoides Blue Lillypilly Syzygium oleosum Prickly Ash Orites excelsa Blue Quandong Elaeocarpus grandis Prickly Tree Fern Cyathea leichhardtiana Blueberry Ash Elaeocarpus reticulatus Purple Cherry Syzygium crebrinerve Blush Walnut Beilschmiedia obtusifolia Red Apple Acmena ingens Bollywood Litsea reticulata Red Ash Alphitonia excelsa Bolwarra Eupomatia laurina Red Bauple Nut Hicksbeachia -

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to Identify the Level of Threat to Plants

Ex-Situ Conservation at Scott Arboretum Public gardens and arboreta are more than just pretty places. They serve as an insurance policy for the future through their well managed ex situ collections. Ex situ conservation focuses on safeguarding species by keeping them in places such as seed banks or living collections. In situ means "on site", so in situ conservation is the conservation of species diversity within normal and natural habitats and ecosystems. The Scott Arboretum is a member of Botanical Gardens Conservation International (BGCI), which works with botanic gardens around the world and other conservation partners to secure plant diversity for the benefit of people and the planet. The aim of BGCI is to ensure that threatened species are secure in botanic garden collections as an insurance policy against loss in the wild. Their work encompasses supporting botanic garden development where this is needed and addressing capacity building needs. They support ex situ conservation for priority species, with a focus on linking ex situ conservation with species conservation in natural habitats and they work with botanic gardens on the development and implementation of habitat restoration and education projects. BGCI uses the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to identify the level of threat to plants. In-depth analyses of the data contained in the IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, Red List are published periodically (usually at least once every four years). The results from the analysis of the data contained in the 2008 update of the IUCN Red List are published in The 2008 Review of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; see www.iucn.org/redlist for further details. -

Reconstructing the Basal Angiosperm Phylogeny: Evaluating Information Content of Mitochondrial Genes

55 (4) • November 2006: 837–856 Qiu & al. • Basal angiosperm phylogeny Reconstructing the basal angiosperm phylogeny: evaluating information content of mitochondrial genes Yin-Long Qiu1, Libo Li, Tory A. Hendry, Ruiqi Li, David W. Taylor, Michael J. Issa, Alexander J. Ronen, Mona L. Vekaria & Adam M. White 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, The University Herbarium, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1048, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence). Three mitochondrial (atp1, matR, nad5), four chloroplast (atpB, matK, rbcL, rpoC2), and one nuclear (18S) genes from 162 seed plants, representing all major lineages of gymnosperms and angiosperms, were analyzed together in a supermatrix or in various partitions using likelihood and parsimony methods. The results show that Amborella + Nymphaeales together constitute the first diverging lineage of angiosperms, and that the topology of Amborella alone being sister to all other angiosperms likely represents a local long branch attrac- tion artifact. The monophyly of magnoliids, as well as sister relationships between Magnoliales and Laurales, and between Canellales and Piperales, are all strongly supported. The sister relationship to eudicots of Ceratophyllum is not strongly supported by this study; instead a placement of the genus with Chloranthaceae receives moderate support in the mitochondrial gene analyses. Relationships among magnoliids, monocots, and eudicots remain unresolved. Direct comparisons of analytic results from several data partitions with or without RNA editing sites show that in multigene analyses, RNA editing has no effect on well supported rela- tionships, but minor effect on weakly supported ones. Finally, comparisons of results from separate analyses of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes demonstrate that mitochondrial genes, with overall slower rates of sub- stitution than chloroplast genes, are informative phylogenetic markers, and are particularly suitable for resolv- ing deep relationships. -

Rare Or Threatened Vascular Plant Species of Wollemi National Park, Central Eastern New South Wales

Rare or threatened vascular plant species of Wollemi National Park, central eastern New South Wales. Stephen A.J. Bell Eastcoast Flora Survey PO Box 216 Kotara Fair, NSW 2289, AUSTRALIA Abstract: Wollemi National Park (c. 32o 20’– 33o 30’S, 150o– 151oE), approximately 100 km north-west of Sydney, conserves over 500 000 ha of the Triassic sandstone environments of the Central Coast and Tablelands of New South Wales, and occupies approximately 25% of the Sydney Basin biogeographical region. 94 taxa of conservation signiicance have been recorded and Wollemi is recognised as an important reservoir of rare and uncommon plant taxa, conserving more than 20% of all listed threatened species for the Central Coast, Central Tablelands and Central Western Slopes botanical divisions. For a land area occupying only 0.05% of these divisions, Wollemi is of paramount importance in regional conservation. Surveys within Wollemi National Park over the last decade have recorded several new populations of signiicant vascular plant species, including some sizeable range extensions. This paper summarises the current status of all rare or threatened taxa, describes habitat and associated species for many of these and proposes IUCN (2001) codes for all, as well as suggesting revisions to current conservation risk codes for some species. For Wollemi National Park 37 species are currently listed as Endangered (15 species) or Vulnerable (22 species) under the New South Wales Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995. An additional 50 species are currently listed as nationally rare under the Briggs and Leigh (1996) classiication, or have been suggested as such by various workers. Seven species are awaiting further taxonomic investigation, including Eucalyptus sp. -

Fauna Survey, Wingham Management Area, Port Macquarie Region

This document has been scanned from hard-copy archives for research and study purposes. Please note not all information may be current. We have tried, in preparing this copy, to make the content accessible to the widest possible audience but in some cases we recognise that the automatic text recognition maybe inadequate and we apologise in advance for any inconvenience this may cause. FOREST RESOURCES SERIES NO. 19 FAUNA SURVEY, WINGHAM MANAGEMENT AREA, PORT MACQUARIE REGION PART 1. MAMMALS BY ALAN YORK \ \ FORESTRY COMMISSION OF NEW SOUTH WALES ----------------------------- FAUNA SURVEY, WINGHAM MANAGEMENT AREA, PORT MACQUARIE REGION PART 1. MAMMALS by ALAN YORK FOREST ECOLOGY SECTION WOOD TECHNOLOGY AND FOREST RESEARCH DIVISION FORESTRY COMMISSION OF NEW SOUTH WALES SYDNEY 1992 Forest Resources Series No. 19 March 1992 The Author: AIan York, BSc.(Hons.) PhD., Wildlife Ecologist, Forest Ecology Section, Wood Technology and Forest Research Division, Forestry Commission ofNew South Wales. Published by: Forestry Commission ofNew South Wales, Wood Technology and Forest Research Division, 27 Oratava Avenue, West Pennant Hills, 2125 P.O. Box lOO, Beecroft 2119 Australia. Copyright © 1992 by Forestry Commission ofNew South Wales ODC 156.2:149 (944) ISSN 1033-1220 ISBN 07305 5663 8 Fauna Survey, Wingham Management Area, -i- PortMacquarie Region Part 1. Mammals TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 1. The Wingham Management Area 1 (a) Location 1 (b) Physical environment 3 (c) Vegetation communities 3 (d) Fire 5 (e) Timber harvesting : 5 SURVEY METHODOLOGy 7 1. Overall Sampling Strategy 7 (a) General survey 7 (b) Plot-based survey 7 (i) Stratification 1:Jy Broad Forest Type : 8 (ii) Stratification by Altitude 8 (iii) Stratification 1:Jy Management History 8 (iv) Plot selection 9 (v) Special considerations 9 (vi) Plot establishment 10 (vii) Plot design........................................................................................................... -

RIVERDENE TUBESTOCK (50X50x150mm)

RIVERDENE TUBESTOCK (50x50x150mm) KEY : B= Bushtucker G= Grass F = Fodder A = Aquatic T = Timber Production C = Groundcover O = Ornamental (non Native) FN – Fern V – Vine/Climber NAME COMMON NAME COMMENT sandstone areas of the Bulga & Putty districts. Frost & sweetly scented yellow flowers. Grows to 1.5m. Abrophyllum ornans - Native Hydrangea- Tall shrub or drought hardy. Responds well to regular pruning. small tree from 3-6m high. Attractive bushy shrub, best Acacia buxifolia - Box Leaf Wattle - Evergreen shrub to B Acacia decurrens - Green Wattle - A fast growing small in a cool moist position in well drained soils. Ideal with 2m, blue green foliage and massed golden yellow to intermediate spreading tree with attractive dark green ferns. Flowers yellowish white & fragrant. Hardy to light flowers. Best in well drained soils but will withstand short fern-like foliage, & large racemes of yellow ball-flowers in drought only. periods of waterlogging. Full or part shade. Winter. Acacia amblygona - Fan Wattle - Small, spreading shrub Acacia concurrens –Curracabah - Shrub or small tree to Acacia doratoxylon – Currawong - Tall shrub or small ranging from completely prostrate in habit to about 1.5 8m high. Rod like flowers, bright yellow in spring. Very tree up to 8 meters high. Best in well drained soil in full metres high. It has bright yellow flowers over winter and hardy & useful small shade tree. Best in full sun & well sun or dappled shade. Useful forage for farm stock. spring. Likes well drained soils and sunny aspect. drained soil. Frost hardy. Hardy to frost and drought when established. Acacia barringtonensis – Barrington - Decorative shrub Acacia coriacea – Wirewood - Tall shrub 4-5m high. -

Kew Science Publications for the Academic Year 2017–18

KEW SCIENCE PUBLICATIONS FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR 2017–18 FOR THE ACADEMIC Kew Science Publications kew.org For the academic year 2017–18 ¥ Z i 9E ' ' . -,i,c-"'.'f'l] Foreword Kew’s mission is to be a global resource in We present these publications under the four plant and fungal knowledge. Kew currently has key questions set out in Kew’s Science Strategy over 300 scientists undertaking collection- 2015–2020: based research and collaborating with more than 400 organisations in over 100 countries What plants and fungi occur to deliver this mission. The knowledge obtained 1 on Earth and how is this from this research is disseminated in a number diversity distributed? p2 of different ways from annual reports (e.g. stateoftheworldsplants.org) and web-based What drivers and processes portals (e.g. plantsoftheworldonline.org) to 2 underpin global plant and academic papers. fungal diversity? p32 In the academic year 2017-2018, Kew scientists, in collaboration with numerous What plant and fungal diversity is national and international research partners, 3 under threat and what needs to be published 358 papers in international peer conserved to provide resilience reviewed journals and books. Here we bring to global change? p54 together the abstracts of some of these papers. Due to space constraints we have Which plants and fungi contribute to included only those which are led by a Kew 4 important ecosystem services, scientist; a full list of publications, however, can sustainable livelihoods and natural be found at kew.org/publications capital and how do we manage them? p72 * Indicates Kew staff or research associate authors. -

Pdf Environment and Conservation, Hurstville

References and further reading Scientific Committee (2015). Hibbertia sp. Turramurra Final Determination NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee. Keith, D.A. (2004). Ocean shores to desert dunes: the native Available from www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/ vegetation of New South Wales and the A.C.T. Department of threatenedspecies/determinations/FDHibbTurraCR.pdf Environment and Conservation, Hurstville. Threatened Species Scientific Committee (2016). Conservation OEH (2013). The Native Vegetation of the Sydney Metropolitan Advice Hibbertia spanantha Julian’s hibbertia. Department of the Area (Version 2.0). Office of Environment and Heritage, Environment and Energy, Canberrra. Department of Premier and Cabinet, Sydney. Toelken, H.R. and Robinson, A.F. (2015). Notes on Hibbertia OEH (2017). Julian’s Hibbertia-profile. Office of Environment (Dilleniaceae) 11. Hibbertia spanantha, a new species from the and Heritage NSW Government, Sydney. Accessed 6th central coast of New South Wales. Journal of the Adelaide Botanic February 2018 Available from www.environment.nsw.gov.au/ Gardens 29: 11–14 threatenedSpeciesApp/profile.aspx?id=20279 Threatened plant translocation case study: Wollemia nobilis (Wollemi Pine), Araucariaceae HEIDI ZIMMER1*, PATRICK BAKER2, CATHERINE OFFORD3, JESSICA RIGG4, GREG BOURKE5 AND TONY AULD1 1 NSW Office of Environment and Heritage 2 University of Melbourne 3 The Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan 4 NSW Department of Primary Industries 5 The Blue Mountains Botanic Garden Mount Tomah *Corresponding author: [email protected] The species There are around 200 seedlings and juvenile Wollemi Pines in the wild. It is likely that the creation of canopy The Wollemi Pine is a Critically Endangered conifer that is gaps would increase Wollemi Pine recruitment, as many endemic to a single catchment in Wollemi National Park, rainforest trees. -

Gymnosperms on the EDGE Félix Forest1, Justin Moat 1,2, Elisabeth Baloch1, Neil A

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Gymnosperms on the EDGE Félix Forest1, Justin Moat 1,2, Elisabeth Baloch1, Neil A. Brummitt3, Steve P. Bachman 1,2, Stef Ickert-Bond 4, Peter M. Hollingsworth5, Aaron Liston6, Damon P. Little7, Sarah Mathews8,9, Hardeep Rai10, Catarina Rydin11, Dennis W. Stevenson7, Philip Thomas5 & Sven Buerki3,12 Driven by limited resources and a sense of urgency, the prioritization of species for conservation has Received: 12 May 2017 been a persistent concern in conservation science. Gymnosperms (comprising ginkgo, conifers, cycads, and gnetophytes) are one of the most threatened groups of living organisms, with 40% of the species Accepted: 28 March 2018 at high risk of extinction, about twice as many as the most recent estimates for all plants (i.e. 21.4%). Published: xx xx xxxx This high proportion of species facing extinction highlights the urgent action required to secure their future through an objective prioritization approach. The Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) method rapidly ranks species based on their evolutionary distinctiveness and the extinction risks they face. EDGE is applied to gymnosperms using a phylogenetic tree comprising DNA sequence data for 85% of gymnosperm species (923 out of 1090 species), to which the 167 missing species were added, and IUCN Red List assessments available for 92% of species. The efect of diferent extinction probability transformations and the handling of IUCN data defcient species on the resulting rankings is investigated. Although top entries in our ranking comprise species that were expected to score well (e.g. Wollemia nobilis, Ginkgo biloba), many were unexpected (e.g. -

NSW Rainforest Trees Part

This document has been scanned from hard-copy archives for research and study purposes. Please note not all information may be current. We have tried, in preparing this copy, to make the content accessible to the widest possible audience but in some cases we recognise that the automatic text recognition maybe inadequate and we apologise in advance for any inconvenience this may cause. N.S.W. RAINFOREST TREES PART XII FAMILIES: LONGANIACEAE APOCYNACEAE BORAGINACEAE VERBENACEAE SOLANACEAE MYOPORACEAE RUBIACEAE ASTERACEAE AUTHOR A.G. FLOYD FORESTRY COMMISSION OF N.S.W. SYDNEY, 1983 Forestry Commission ofN.SW. 95-99 York Street, Sydney, New South Wales 2000 Australia Published 1983 THE AUTHOR- Mr A. G. Floyd is a rainforest specialist on the staff of The National Parks and Wildlife Service of New South Wales based at Coffs Harbour, New South Wales. National Library of Australia card number ISSN 0085-3984 ISBN 0 7240 7608 5 2 INTRODUCTION This is the final part in a series of twelve research notes of the Forestry Commission of N.S.W. describing the rainforest trees of the state. Current publications by the same author are: Research Note No. 3 (1960) Second Edition 1979 - N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part 1, FamilY,Lauraceae. Research Note No. 7 (1961) Second Edition 1981 - N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part H, Families Capparidaceae, Escalloniaceae, Pittosporaceae, Cunoniaceae, Davidsoniaceae. Research Note No. 28 (1973) Second Edition 1979 - N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part Ill, Family Myrtaceae. Research Note No. 29 (1976) Second Edition 1979 - N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part IV, Family Rutaceae. -

Wollemi Pine (Wollemia Nobilis) and Its Introduction to Cultivation in Great Britain and Ireland©

432 Combined Proceedings International Plant Propagators’ Society, Volume 58, 2008 Wollemi Pine (Wollemia nobilis) and Its Introduction to Cultivation in Great Britain and Ireland© Mark Taylor Kernock Park Plants, Pillaton, Saltash, Cornwall PL12 6RY Email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Wollemi pine (Wollemia nobilis) was discovered within the Wollemi National Park, a virtually untouched wilderness area of 361,000 ha in the Blue Mountains, 200 km north west of Sydney Australia. It was found on 10 Sept. 1994, when a park ranger was exploring the deep canyons in the park. Wollemi is an Australian Ab- original word which means “stop, and look around you.” The ranger, David Noble, knew most of the tree species in the Park and he must have followed this Aboriginal saying when he stumbled across a grove of enormous trees unlike any that he had seen before. When I spoke to him on his visit to the U.K. in April 2006, he said it was a very strange sensation being in that canyon and even then, it evoked feelings and thoughts of the fairly recent film of that time, Jurassic Park. Noble collected a section of foliage to show his colleagues at the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service. It was soon established that the tree belonged to the Araucariaceae, the same family as the monkey puzzle, Norfolk Island pine, and less well known trees such as the hoop, bunya, and kauri pines. Further inves- tigation, including help from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, revealed that this was, in fact, a completely new genus of tree.