An Interview with Nalo Hopkinson Nancy Batty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906 B Culture and Society: Gothic and Horror Prerequisite(s): 1.0 credit in ENGL at the 1000 level or permission of the Department Tuesdays 6:05 – 8:55 pm 182 Unicentre Instructor: Aalya Ahmad, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] Office: 1422 Dunton Tower Office Hours: please email me for an appointment Course Description: This course is an overview of Gothic and Horror fiction as literary genres or fictional modes that reflect and play with prevalent cultural fears and anxieties. Reading short stories that range from excerpts from the eighteenth-century Gothic novels to mid-century weird fiction to contemporary splatterpunk stories, students will also draw upon a wide range of literary and cultural studies theories that analyze and interpret Gothic and horror texts. By the end of this course, students should have a good grasp of the Gothic and Horror field, of its principal theoretical concepts, and be able to apply those concepts to texts more generally. Trigger Warning: This course examines graphic and potentially disturbing material. If you are triggered by anything you experience during this course and require assistance, please see me. Texts: All readings are available through the library or on ARES. Please note: where excerpts are indicated, students are also encouraged to read the entire text. Evaluation: 15% Journal (4 pages plus works cited list) due January 31 This assignment is designed to provide you with early feedback. In a short journal, please reflect on what you personally have found compelling about Gothic or horror fiction, including a short discussion of a favourite or memorable text(s). -

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This Year’S Trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Was Spent in a Whirl of Activity

EDITORIAL Sheila Williams THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This year’s trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts was spent in a whirl of activity. In addition to academic papers, author readings, banquets, and the awards ceremony, it was a celebration of major life events. Thursday night saw a surprise birthday party for well-known SF and fantasy critic Gary K. Wolfe and a compelling memorial for storied editor David G. Hartwell. Sunday morning brought us the beautiful wedding of Rebecca McNulty and Bernie Goodman. Rebecca met Bernie when she was a finalist for our annual Dell Magazines Award for Undergraduate Ex- cellence in Science Fiction and Fantasy Writing several years ago. Other past finalists were also in attendance at the conference. In addition to Re- becca, it was a joy to watch E. Lily Yu, Lara Donnelly, Rich Larson, and Seth Dickin- son welcome a brand new crop of young writers. The winner of this year’s award was Rani Banjarian, a senior at Vanderbilt University. Rani studied at an international school in Beirut, Lebanon, before coming to the U.S. to attend college. Fluent in Arabic and English, he’s also toying with adding French to his toolbox. Rani is graduating with a duel major in physics and writing. His award winning short story, “Lullabies in Arabic” incorporates his fascination with memoir writing along with a newfound interest in science fiction. My co-judge Rick Wilber and I were once again pleased that the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts and Dell Magazines cosponsored Rani’s expense-paid trip to the conference in Orlando, Florida, and the five hundred dollar prize. -

The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree on April 26, 2009, the James Tiptree, Jr

Spring/Summer 2009 Volume 5 The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree On April 26, 2009, The James Tiptree, Jr. H New Essay Collection from Literary Award Council announced that the Ursula K. Le Guin 2008 Tiptree Award will be going to Patrick Special Features Ness’s young adult novel The Knife of Never Letting Go and Nisi Shawl’s Filter House, an H Hanging out along the Aqueduct…, by Nisi Shawl Aqueduct Press book. page 9 The Tiptree Award, an annual literary prize H L. Timmel Duchamp for science fiction or fantasy “that expands or Interviews Liz Henry about explores our understanding of gender,” will The WisCon Chronicles, Vol. 3 be presented on Memorial Day weekend at page 6 WisCon in Madison, Wisconsin. Each winner H Gwyneth Jones writes about will receive $1000 in prize money, an original The Buonarotti Quartet artwork created specifically for the winning page 2 novel or story, and a confection, usually choco- H Three Observations and a late. The 2008 jurors were Gavin J. Grant Dialogue by Sylvia Kelso page 2 (chair), K. Tempest Bradford, Leslie Howle, Roz Kaveney, and Catherynne M. Valente. In Other News The award is named for Alice B. Sheldon, who wrote under the pseudonym H Aqueduct Celebrates James Tiptree, Jr. By her impulsive choice of a masculine pen name, Sheldon 5th Anniversary cont. on page 5 page 8 H New Spring Releases New from Aqueduct: Ursula K. Le Guin, page 12 Cheek by Jowl Talks and Essays about How and Why Fantasy Matters The monstrous homogenization of our world has now almost destroyed the map, any map, by making every place on it exactly like every other place, and leaving no blanks. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

Creolisation and Black Women's Subjectivities in the Diasporic Science Fiction of Nalo Hopkinson Jacolie

Haunting Temporalities: Creolisation and Black Women's Subjectivities in the Diasporic Science Fiction of Nalo Hopkinson Jacolien Volschenk This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, the Department of English, University of the Western Cape Date submitted for examination: 11 November 2016 Names of supervisors: Dr Alannah Birch and Prof Marika Flockemann i Keywords Diasporic science fiction, temporal entanglement, creolisation, black women’s subjectivities, modernity, slow violence, technology, empire, slavery, Nalo Hopkinson Abstract This study examines temporal entanglement in three novels by Jamaican-born author Nalo Hopkinson. The novels are: Brown Girl in the Ring (1998), Midnight Robber (2000), and The Salt Roads (2004). The study pays particular attention to Hopkinson’s use of narrative temporalities, which are shape by creolisation. I argue that Hopkinson creatively theorises black women’s subjectivities in relation to (post)colonial politics of domination. Specifically, creolised temporalities are presented as a response to predatory Western modernity. Her innovative diasporic science fiction displays common preoccupations associated with Caribbean women writers, such as belonging and exile, and the continued violence enacted by the legacy of colonialism and slavery. A central emphasis of the study is an analysis of how Hopkinson not only employs a past gaze, as the majority of both Caribbean and postcolonial writing does to recover the subaltern subject, but also how she uses the future to reclaim and reconstruct a sense of selfhood and agency, specifically with regards to black women. Linked to the future is her engagement with notions of technological and social betterment and progress as exemplified by her emphasis on the use of technology as a tool of empire. -

W41 PPB-Web.Pdf

The thrilling adventures of... 41 Pocket Program Book May 26-29, 2017 Concourse Hotel Madison Wisconsin #WC41 facebook.com/wisconwiscon.net @wisconsf3 Name/Room No: If you find a named pocket program book, please return it to the registration desk! New! Schedule & Hours Pamphlet—a smaller, condensed version of this Pocket Program Book. Large Print copies of this book are available at the Registration Desk. TheWisSched app is available on Android and iOS. What works for you? What doesn't? Take the post-con survey at wiscon.net/survey to let us know! Contents EVENTS Welcome to WisCon 41! ...........................................1 Art Show/Tiptree Auction Display .........................4 Tiptree Auction ..........................................................6 Dessert Salon ..............................................................7 SPACES Is This Your First WisCon?.......................................8 Workshop Sessions ....................................................8 Childcare .................................................................. 10 Children's and Teens' Programming ..................... 11 Children's Schedule ................................................ 11 Teens' Schedule ....................................................... 12 INFO Con Suite ................................................................. 12 Dealers’ Room .......................................................... 14 Gaming ..................................................................... 15 Quiet Rooms .......................................................... -

229 INDEX © in This Web Service Cambridge

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05246-8 - The Cambridge Companion to: American Science Fiction Edited by Eric Carl Link and Gerry Canavan Index More information INDEX Aarseth, Espen, 139 agency panic, 49 Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (fi lm, Agents of SHIELD (television, 2013–), 55 1948), 113 Alas, Babylon (Frank, 1959), 184 Abbott, Carl, 173 Aldiss, Brian, 32 Abrams, J.J., 48 , 119 Alexie, Sherman, 55 Abyss, The (fi lm, Cameron 1989), 113 Alias (television, 2001–06, 48 Acker, Kathy, 103 Alien (fi lm, Scott 1979), 116 , 175 , 198 Ackerman, Forrest J., 21 alien encounters Adam Strange (comic book), 131 abduction by aliens, 36 Adams, Neal, 132 , 133 Afrofuturism and, 60 Adventures of Superman, The (radio alien abduction narratives, 184 broadcast, 1946), 130 alien invasion narratives, 45–50 , 115 , 184 African American science fi ction. assimilation of human bodies, 115 , 184 See also Afrofuturism ; race assimilation/estrangement dialectic African American utopianism, 59 , 88–90 and, 176 black agency in Hollywood SF, 116 global consciousness and, 1 black genius fi gure in, 59 , 60 , 62 , 64 , indigenous futurism and, 177 65 , 67 internal “Aliens R US” motif, 119 blackness as allegorical SF subtext, 120 natural disasters and, 47 blaxploitation fi lms, 117 post-9/11 reformulation of, 45 1970s revolutionary themes, 118 reverse colonization narratives, 45 , 174 nineteenth century SF and, 60 in space operas, 23 sexuality and, 60 Superman as alien, 128 , 129 Afrofuturism. See also African American sympathetic treatment of aliens, 38 , 39 , science fi ction ; race 50 , 60 overview, 58 War of the Worlds and, 1 , 3 , 143 , 172 , 174 African American utopianism, 59 , 88–90 wars with alien races, 3 , 7 , 23 , 39 , 40 Afrodiasporic magic in, 65 Alien Nation (fi lm, Baker 1988), 119 black racial superiority in, 61 Alien Nation (television, 1989–1990), 120 future race war theme, 62 , 64 , 89 , 95n17 Alien Trespass (fi lm, 2009), 46 near-future focus in, 61 Alien vs. -

'Race' and Technology in Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight Robber

This article was downloaded by: [University of Cambridge] On: 22 October 2014, At: 02:40 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK African Identities Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cafi20 Vanishing bodies: ‘race’ and technology in Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight robber Elizabeth Boyle a a University of Chester , Chester, UK Published online: 21 May 2009. To cite this article: Elizabeth Boyle (2009) Vanishing bodies: ‘race’ and technology in Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight robber , African Identities, 7:2, 177-191, DOI: 10.1080/14725840902808868 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14725840902808868 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Introduction Imagining the Future of Climate Change

Introduction Imagining the Future of Climate Change In Bong Joon-Ho’s 2013 international blockbuster Snowpiercer, a single train traverses the globe, protecting the fi nal remnant of humanity from an Ice Age that made the planet seemingly unin- habitable. Set in 2031, the fi lm begins by squarely placing the blame on humans for this catastrophic climate change. As the opening credits roll over dark, starry space, we hear crackling, fuzzy excerpts of news broadcasts from all over the world telling how, despite protests from environmental groups and “developing coun- tries,” on 1 July 2014, seventy countries dispersed the artifi cial cool- ing substance CW-7 into the upper layers of the atmosphere. Because “global warming can no longer be ignored,” one of the dis- embodied voices explains, seeding the skies with CW-7 was a last- ditch eff ort “to bring average global temperatures down to man- ageable levels as a revolutionary solution to mankind’s warming of the planet.” But before the real action of the fi lm even starts, we learn the grim outcome of this desperate international scientifi c experiment. Two short sentences loom large on the screen: “Soon after dispersing CW-7 the world froze. All life became extinct.” 1 2 / Introduction In imagining a geo-engineering experiment gone wrong in response to the disaster of global warming, Bong is asking us to think critically about the solution to the problem of climate change that is favored by many people, states, and corporations invested in fi nding alternatives to curbing carbon emissions.1 In addition, since the mid-2000s, some prominent scientists, such as Dutch Nobel Prize-winning atmospheric chemist Paul Crut- zen, have also advocated exploring geo-engineering out of fears that states will not take the necessary actions to curb global warming in time and that we are on the brink of locking in dys- topian climate change that will render unsustainable life on Earth as we know it. -

Professor Shelley Streeby ETHN 182: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Fantasy and Science Fiction Center 222, 12:30-1:50 Office Location: Social Sciences Bldg

1 Professor Shelley Streeby ETHN 182: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Fantasy and Science Fiction Center 222, 12:30-1:50 Office Location: Social Sciences Bldg. Room 223; Phone: 858.534.1739; E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: W 1:00-3:00 and by appointment This seminar focuses on visions of race, gender, and sexuality in 20th and 21st century fantasy and science fiction. Partly in response to political and social movements and changing media politics, diverse forms of fantasy and science fiction in the last 100 years raise provocative questions about race, gender, sexuality, and empire, often on a global scale. Today, science fictions jump between and among multiple platforms, including literature, film, music, television, video games, and the internet. This class explores a variety of cultural forms in order to understand such visions of race, gender, and sexuality in comparative, transmedia contexts. During the quarter, we will compare and connect works of fantasy and science fiction produced by several different groups, including Black Diasporans, Latinas/os, whites, indigenous people, and Asian Americans. We will read short essays on these identity categories as well as other keywords as we seek to develop an intersectional perspective. On the one hand, race, gender, sexuality, and empire have always been central to the fantasy and science fiction genres as they emerged in the 19th and early 20th centuries: figures such as the alien, the last man, the zombie, and the vampire are inseparable from histories of gender and sexuality, race relations and colonial contact, violence, and settlement, as are tropes of space exploration and founding new worlds, terraforming, and digital embodiment. -

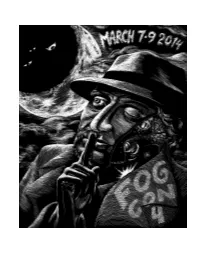

Fogcon 4 Program

Contents Comments from the Chair By Guy W. Thomas 2 Convention Committee 2 Honored Guest Tim Powers By Cliff Winnig 3 Honored Guest Seanan McGuire By Tanya Huff 4 Honored Ghost James Tiptree, Jr. By Jeffrey Smith 5 About Cons – Interviews with some of our guests 6 Everything but the Signature Is Me By James Tiptree, Jr. 10 Hotel 14 Registration 15 Consuite 15 Dealers’ Room 15 Game Room 15 Safety Team 15 Programming, Friday March 7, 2014 17 Programming, Saturday, March 8, 2014 20 Programming, Sunday, March 9, 2014 26 Program Participants 28 Access Information 36 Anti-Harassment Policy 39 Photography Policy 39 FOGcon 4 – Hours and Useful Information Back Cover Editor: Kerry Ellis; Proofreaders: Lynn Alden Kendall, Wendy Shaffer, Guy W. Thomas, Aaron I. Spielman and Debbie Notkin Cover: Art by Eli Bishop; Printed on 30% recycled PCW acid free paper Printed on 100% recycled PCW acid free paper. FOGcon 4 is a project done jointly by Friends of Genre and the Speculative Literature Foundation. Copyright © 2014 FOGcon 4. All Rights Revert to the Authors and Artists. 1 Comments from the Chair By Guy W. Thomas Welcome to FOGcon 4! Once again we bring you the convention by the Bay. FOGcon has always been a convention by and for genre fiction fans. This is our party, our celebration. The theme this year is Secrets. The secret I learned about running conventions from the founder and chair of the first three FOGcons, the radiant and perspicacious Vylar Kaftan is: find cool, talented people who also want to put on a convention and that you like hanging out with anyway.