Read Excerpt (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906 B Culture and Society: Gothic and Horror Prerequisite(s): 1.0 credit in ENGL at the 1000 level or permission of the Department Tuesdays 6:05 – 8:55 pm 182 Unicentre Instructor: Aalya Ahmad, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] Office: 1422 Dunton Tower Office Hours: please email me for an appointment Course Description: This course is an overview of Gothic and Horror fiction as literary genres or fictional modes that reflect and play with prevalent cultural fears and anxieties. Reading short stories that range from excerpts from the eighteenth-century Gothic novels to mid-century weird fiction to contemporary splatterpunk stories, students will also draw upon a wide range of literary and cultural studies theories that analyze and interpret Gothic and horror texts. By the end of this course, students should have a good grasp of the Gothic and Horror field, of its principal theoretical concepts, and be able to apply those concepts to texts more generally. Trigger Warning: This course examines graphic and potentially disturbing material. If you are triggered by anything you experience during this course and require assistance, please see me. Texts: All readings are available through the library or on ARES. Please note: where excerpts are indicated, students are also encouraged to read the entire text. Evaluation: 15% Journal (4 pages plus works cited list) due January 31 This assignment is designed to provide you with early feedback. In a short journal, please reflect on what you personally have found compelling about Gothic or horror fiction, including a short discussion of a favourite or memorable text(s). -

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This Year’S Trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Was Spent in a Whirl of Activity

EDITORIAL Sheila Williams THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This year’s trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts was spent in a whirl of activity. In addition to academic papers, author readings, banquets, and the awards ceremony, it was a celebration of major life events. Thursday night saw a surprise birthday party for well-known SF and fantasy critic Gary K. Wolfe and a compelling memorial for storied editor David G. Hartwell. Sunday morning brought us the beautiful wedding of Rebecca McNulty and Bernie Goodman. Rebecca met Bernie when she was a finalist for our annual Dell Magazines Award for Undergraduate Ex- cellence in Science Fiction and Fantasy Writing several years ago. Other past finalists were also in attendance at the conference. In addition to Re- becca, it was a joy to watch E. Lily Yu, Lara Donnelly, Rich Larson, and Seth Dickin- son welcome a brand new crop of young writers. The winner of this year’s award was Rani Banjarian, a senior at Vanderbilt University. Rani studied at an international school in Beirut, Lebanon, before coming to the U.S. to attend college. Fluent in Arabic and English, he’s also toying with adding French to his toolbox. Rani is graduating with a duel major in physics and writing. His award winning short story, “Lullabies in Arabic” incorporates his fascination with memoir writing along with a newfound interest in science fiction. My co-judge Rick Wilber and I were once again pleased that the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts and Dell Magazines cosponsored Rani’s expense-paid trip to the conference in Orlando, Florida, and the five hundred dollar prize. -

The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree on April 26, 2009, the James Tiptree, Jr

Spring/Summer 2009 Volume 5 The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree On April 26, 2009, The James Tiptree, Jr. H New Essay Collection from Literary Award Council announced that the Ursula K. Le Guin 2008 Tiptree Award will be going to Patrick Special Features Ness’s young adult novel The Knife of Never Letting Go and Nisi Shawl’s Filter House, an H Hanging out along the Aqueduct…, by Nisi Shawl Aqueduct Press book. page 9 The Tiptree Award, an annual literary prize H L. Timmel Duchamp for science fiction or fantasy “that expands or Interviews Liz Henry about explores our understanding of gender,” will The WisCon Chronicles, Vol. 3 be presented on Memorial Day weekend at page 6 WisCon in Madison, Wisconsin. Each winner H Gwyneth Jones writes about will receive $1000 in prize money, an original The Buonarotti Quartet artwork created specifically for the winning page 2 novel or story, and a confection, usually choco- H Three Observations and a late. The 2008 jurors were Gavin J. Grant Dialogue by Sylvia Kelso page 2 (chair), K. Tempest Bradford, Leslie Howle, Roz Kaveney, and Catherynne M. Valente. In Other News The award is named for Alice B. Sheldon, who wrote under the pseudonym H Aqueduct Celebrates James Tiptree, Jr. By her impulsive choice of a masculine pen name, Sheldon 5th Anniversary cont. on page 5 page 8 H New Spring Releases New from Aqueduct: Ursula K. Le Guin, page 12 Cheek by Jowl Talks and Essays about How and Why Fantasy Matters The monstrous homogenization of our world has now almost destroyed the map, any map, by making every place on it exactly like every other place, and leaving no blanks. -

Jon Boorstin's the Newsboys' Lodging-House

July-August 2004 NEWSBOY Page 1 VOLUME XLII JULY-AUGUST 2004 NUMBER 4 Jon Boorstin’s The Newsboys’ Lodging-House A review -- See Page 3 Daubs and botches Edward Stratemeyer and the artwork for Dave Porter’s Return to School -- See Page 9 Page 2 NEWSBOY July-August 2004 HORATIO ALGER SOCIETY To further the philosophy of Horatio Alger, Jr. and to encourage the spirit of Strive and Succeed that for half a century guided Alger’s President's column undaunted heroes — younngsters whose struggles epitomized the Great American Dream and inspired hero ideals in countless millions of young Americans for generations to come. Summer is over, fall has arrived and everyone is get- OFFICERS ting ready for the winter months. Like everyone says, the ROBERT R. ROUTHIER PRESIDENT older you get the faster the summers go! I sincerely hope MICHAEL MORLEY VICE-PRESIDENT that the summer was a success, not only with family, CHRISTINE DeHAAN TREASURER but just maybe you found a great Horatio Alger book ROBERT E. KASPER EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR in you hunt. If you did, please share it with the Society BBOARD OF DIRECTORS in Newsboy. ERNARD A. BIBERDORF (2005) DIRECTOR My apologies to Chris DeHaan for not including her JIM THORP (2005) DIRECTOR in my last column. I am sure that the society appreciates STEVEN N. SUTTON (2005) DIRECTOR her for the terrific job that she is doing and has done as BART J. NYBERG (2006) DIRECTOR our treasurer. Thanks Chris!! DAVID J. YARINGTON (2006) DIRECTOR Next year’s convention is in place for Grand Rapids, ARTHUR W. -

Creolisation and Black Women's Subjectivities in the Diasporic Science Fiction of Nalo Hopkinson Jacolie

Haunting Temporalities: Creolisation and Black Women's Subjectivities in the Diasporic Science Fiction of Nalo Hopkinson Jacolien Volschenk This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, the Department of English, University of the Western Cape Date submitted for examination: 11 November 2016 Names of supervisors: Dr Alannah Birch and Prof Marika Flockemann i Keywords Diasporic science fiction, temporal entanglement, creolisation, black women’s subjectivities, modernity, slow violence, technology, empire, slavery, Nalo Hopkinson Abstract This study examines temporal entanglement in three novels by Jamaican-born author Nalo Hopkinson. The novels are: Brown Girl in the Ring (1998), Midnight Robber (2000), and The Salt Roads (2004). The study pays particular attention to Hopkinson’s use of narrative temporalities, which are shape by creolisation. I argue that Hopkinson creatively theorises black women’s subjectivities in relation to (post)colonial politics of domination. Specifically, creolised temporalities are presented as a response to predatory Western modernity. Her innovative diasporic science fiction displays common preoccupations associated with Caribbean women writers, such as belonging and exile, and the continued violence enacted by the legacy of colonialism and slavery. A central emphasis of the study is an analysis of how Hopkinson not only employs a past gaze, as the majority of both Caribbean and postcolonial writing does to recover the subaltern subject, but also how she uses the future to reclaim and reconstruct a sense of selfhood and agency, specifically with regards to black women. Linked to the future is her engagement with notions of technological and social betterment and progress as exemplified by her emphasis on the use of technology as a tool of empire. -

Losingsightliterature.Pdf (126.6Kb)

Manno 1 Lindsey Manno Capstone Final Professor Cohen Losing Sight of Literature: The Commodity of Book Packaging In every young writer’s heart there is a dream, a dream that one day all of their hard work will lead to a successful, published novel. And not just any novel, but the next Great American novel that will be taught in classes for decades to come. Unfortunately, much of the publishing industry has another goal in mind when weeding through submissions and story ideas: making money and duplicating the success of Harry Potter or Twilight . In this paper, I plan to examine the workings of companies like Alloy Entertainment and James Frey’s Full Fathom Five Factory, each of which provide outlines and hire writers to put together novels for the Young Adult (YA hereafter) genre. By using a “novel by committee” format, these companies are weakening the publishing industry and making it that much more difficult for an up and coming writer to get their original work seen, much less published. They are doing away with what is considered to be the author and replacing it with brand names and product placement, changing the ideals of what it is to be a writer. In this essay, I will question whether or not these precooked ideas can still be considered art with any literary value, or if they’re simply commodities to companies consumed with the desire for money rather than the desire to share good books. First, though, it is important to determine what it is that allows something to be considered literature or to have literary value. -

Series Books Through the Lens of History by David M

Series Books Through the Lens of History by David M. Baumann This article first appeared in The Mystery and Adventure Series Review #43, summer 2010 Books As Time Machines It was more than half a century ago that I learned how to type. My parents had a Smith-Corona typewriter—manual, of course—that I used to write letters to my cousins. A few years later I took a “typing class” in junior high. Students were encouraged to practice “touch typing” and to aim for a high number of “words per minute”. There were distinctive sounds associated with typing that I can still hear in my memory. I remember the firm and rapid tap of the keys, much more “solid” than the soft burr of computer “keyboarding”. A tiny bell rang to warn me that the end of the line was coming; I would finish the word or insert a hyphen, and then move the platen from left to right with a quick whirring ratchet of motion. Frequently there was the sound of a sheet of paper being pulled out of the machine, either with a rip of frustration accompanied by an impatient crumple and toss, or a careful tug followed by setting the completed page aside; then another sheet was inserted with the roll of the platen until the paper was deftly positioned. Now and then I had to replace a spool of inked ribbon and clean the keys with an old toothbrush. Musing on these nearly vanished sounds, I put myself in the place of the writers of our series books, nearly all of whom surely wrote with typewriters. -

'Race' and Technology in Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight Robber

This article was downloaded by: [University of Cambridge] On: 22 October 2014, At: 02:40 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK African Identities Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cafi20 Vanishing bodies: ‘race’ and technology in Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight robber Elizabeth Boyle a a University of Chester , Chester, UK Published online: 21 May 2009. To cite this article: Elizabeth Boyle (2009) Vanishing bodies: ‘race’ and technology in Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight robber , African Identities, 7:2, 177-191, DOI: 10.1080/14725840902808868 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14725840902808868 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

L. Frank Baum's Boys' Series Books

March-April 2007The horatio NEWSBOY Alger Society Page 1 OFFICIAL PUBLICATION A magazine devoted to the study of Horatio Alger, Jr., his life, works, and influence on the culture of America. VOLUME XLV MARCH-APRIL 2007 NUMBER 2 L. Frank Baum’s boys’ series books -- See Page 7 Final 2007 convention preview ‘Seeking Fortune in Shelbyville’ -- See Pages 3, 5 Page 2 NEWSBOY March-April 2007 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 HORATIO ALGER SOCIETY 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 To further the philosophy of Horatio Alger, Jr. and to encourage the 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 spirit of Strive and Succeed that for half a century guided Alger’s 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 -

Aug 2007.Qxd

RIDINGRIDING RAILWAYS RAILWAYS NEWSLETTER RAILROADER Grand Scales AUGUST 2007 Q u a r t e r l y ello and welcome to the August issue of the Riding Railways Newsletter. One last reminder about the upcoming Miniature Railroad Convention in Missouri. If you haven’t yet made your reservations, I Ham told that rooms are filling up fast in the surrounding areas. And it is much easier on the convention staff if you register early. So please, if you are planning on attending, visit the web site below and register right away. I know Greg is looking forward to visiting with everyone and that the railroad crew has been working diligently to put on a great program for you. Wanted to give everyone a heads up on a new DVD release. In late September we hope to have the first three volumes of the GRAND SCALE UNIVERSITY series available. (Those who attend the convention may be able to purchase the DVDs there.) These DVDs are taken from seminars given at the Hillcrest & Wahtoke RR during our second Grand Scales Convention. These six DVDs will be filled with information especially helpful for those building and operating a Grand Scale operation but will be useful to anyone in the railroad hobby. More information will be available in next month’s newsletter as well as our web site gift shop when they become available. For now, I hope you enjoy this month’s newsletter. Regards, POLICE RAIL BUS here is a very interesting chap Tin England named Peter Jones who often stumbles across (and models) the most interesting rail- way equipment. -

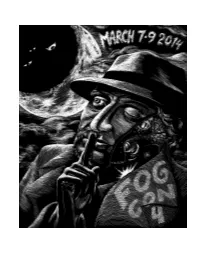

Fogcon 4 Program

Contents Comments from the Chair By Guy W. Thomas 2 Convention Committee 2 Honored Guest Tim Powers By Cliff Winnig 3 Honored Guest Seanan McGuire By Tanya Huff 4 Honored Ghost James Tiptree, Jr. By Jeffrey Smith 5 About Cons – Interviews with some of our guests 6 Everything but the Signature Is Me By James Tiptree, Jr. 10 Hotel 14 Registration 15 Consuite 15 Dealers’ Room 15 Game Room 15 Safety Team 15 Programming, Friday March 7, 2014 17 Programming, Saturday, March 8, 2014 20 Programming, Sunday, March 9, 2014 26 Program Participants 28 Access Information 36 Anti-Harassment Policy 39 Photography Policy 39 FOGcon 4 – Hours and Useful Information Back Cover Editor: Kerry Ellis; Proofreaders: Lynn Alden Kendall, Wendy Shaffer, Guy W. Thomas, Aaron I. Spielman and Debbie Notkin Cover: Art by Eli Bishop; Printed on 30% recycled PCW acid free paper Printed on 100% recycled PCW acid free paper. FOGcon 4 is a project done jointly by Friends of Genre and the Speculative Literature Foundation. Copyright © 2014 FOGcon 4. All Rights Revert to the Authors and Artists. 1 Comments from the Chair By Guy W. Thomas Welcome to FOGcon 4! Once again we bring you the convention by the Bay. FOGcon has always been a convention by and for genre fiction fans. This is our party, our celebration. The theme this year is Secrets. The secret I learned about running conventions from the founder and chair of the first three FOGcons, the radiant and perspicacious Vylar Kaftan is: find cool, talented people who also want to put on a convention and that you like hanging out with anyway.