'Race' and Technology in Nalo Hopkinson's Midnight Robber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906 B Culture and Society: Gothic and Horror Prerequisite(s): 1.0 credit in ENGL at the 1000 level or permission of the Department Tuesdays 6:05 – 8:55 pm 182 Unicentre Instructor: Aalya Ahmad, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] Office: 1422 Dunton Tower Office Hours: please email me for an appointment Course Description: This course is an overview of Gothic and Horror fiction as literary genres or fictional modes that reflect and play with prevalent cultural fears and anxieties. Reading short stories that range from excerpts from the eighteenth-century Gothic novels to mid-century weird fiction to contemporary splatterpunk stories, students will also draw upon a wide range of literary and cultural studies theories that analyze and interpret Gothic and horror texts. By the end of this course, students should have a good grasp of the Gothic and Horror field, of its principal theoretical concepts, and be able to apply those concepts to texts more generally. Trigger Warning: This course examines graphic and potentially disturbing material. If you are triggered by anything you experience during this course and require assistance, please see me. Texts: All readings are available through the library or on ARES. Please note: where excerpts are indicated, students are also encouraged to read the entire text. Evaluation: 15% Journal (4 pages plus works cited list) due January 31 This assignment is designed to provide you with early feedback. In a short journal, please reflect on what you personally have found compelling about Gothic or horror fiction, including a short discussion of a favourite or memorable text(s). -

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This Year’S Trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Was Spent in a Whirl of Activity

EDITORIAL Sheila Williams THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This year’s trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts was spent in a whirl of activity. In addition to academic papers, author readings, banquets, and the awards ceremony, it was a celebration of major life events. Thursday night saw a surprise birthday party for well-known SF and fantasy critic Gary K. Wolfe and a compelling memorial for storied editor David G. Hartwell. Sunday morning brought us the beautiful wedding of Rebecca McNulty and Bernie Goodman. Rebecca met Bernie when she was a finalist for our annual Dell Magazines Award for Undergraduate Ex- cellence in Science Fiction and Fantasy Writing several years ago. Other past finalists were also in attendance at the conference. In addition to Re- becca, it was a joy to watch E. Lily Yu, Lara Donnelly, Rich Larson, and Seth Dickin- son welcome a brand new crop of young writers. The winner of this year’s award was Rani Banjarian, a senior at Vanderbilt University. Rani studied at an international school in Beirut, Lebanon, before coming to the U.S. to attend college. Fluent in Arabic and English, he’s also toying with adding French to his toolbox. Rani is graduating with a duel major in physics and writing. His award winning short story, “Lullabies in Arabic” incorporates his fascination with memoir writing along with a newfound interest in science fiction. My co-judge Rick Wilber and I were once again pleased that the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts and Dell Magazines cosponsored Rani’s expense-paid trip to the conference in Orlando, Florida, and the five hundred dollar prize. -

The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree on April 26, 2009, the James Tiptree, Jr

Spring/Summer 2009 Volume 5 The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree On April 26, 2009, The James Tiptree, Jr. H New Essay Collection from Literary Award Council announced that the Ursula K. Le Guin 2008 Tiptree Award will be going to Patrick Special Features Ness’s young adult novel The Knife of Never Letting Go and Nisi Shawl’s Filter House, an H Hanging out along the Aqueduct…, by Nisi Shawl Aqueduct Press book. page 9 The Tiptree Award, an annual literary prize H L. Timmel Duchamp for science fiction or fantasy “that expands or Interviews Liz Henry about explores our understanding of gender,” will The WisCon Chronicles, Vol. 3 be presented on Memorial Day weekend at page 6 WisCon in Madison, Wisconsin. Each winner H Gwyneth Jones writes about will receive $1000 in prize money, an original The Buonarotti Quartet artwork created specifically for the winning page 2 novel or story, and a confection, usually choco- H Three Observations and a late. The 2008 jurors were Gavin J. Grant Dialogue by Sylvia Kelso page 2 (chair), K. Tempest Bradford, Leslie Howle, Roz Kaveney, and Catherynne M. Valente. In Other News The award is named for Alice B. Sheldon, who wrote under the pseudonym H Aqueduct Celebrates James Tiptree, Jr. By her impulsive choice of a masculine pen name, Sheldon 5th Anniversary cont. on page 5 page 8 H New Spring Releases New from Aqueduct: Ursula K. Le Guin, page 12 Cheek by Jowl Talks and Essays about How and Why Fantasy Matters The monstrous homogenization of our world has now almost destroyed the map, any map, by making every place on it exactly like every other place, and leaving no blanks. -

Creolisation and Black Women's Subjectivities in the Diasporic Science Fiction of Nalo Hopkinson Jacolie

Haunting Temporalities: Creolisation and Black Women's Subjectivities in the Diasporic Science Fiction of Nalo Hopkinson Jacolien Volschenk This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, the Department of English, University of the Western Cape Date submitted for examination: 11 November 2016 Names of supervisors: Dr Alannah Birch and Prof Marika Flockemann i Keywords Diasporic science fiction, temporal entanglement, creolisation, black women’s subjectivities, modernity, slow violence, technology, empire, slavery, Nalo Hopkinson Abstract This study examines temporal entanglement in three novels by Jamaican-born author Nalo Hopkinson. The novels are: Brown Girl in the Ring (1998), Midnight Robber (2000), and The Salt Roads (2004). The study pays particular attention to Hopkinson’s use of narrative temporalities, which are shape by creolisation. I argue that Hopkinson creatively theorises black women’s subjectivities in relation to (post)colonial politics of domination. Specifically, creolised temporalities are presented as a response to predatory Western modernity. Her innovative diasporic science fiction displays common preoccupations associated with Caribbean women writers, such as belonging and exile, and the continued violence enacted by the legacy of colonialism and slavery. A central emphasis of the study is an analysis of how Hopkinson not only employs a past gaze, as the majority of both Caribbean and postcolonial writing does to recover the subaltern subject, but also how she uses the future to reclaim and reconstruct a sense of selfhood and agency, specifically with regards to black women. Linked to the future is her engagement with notions of technological and social betterment and progress as exemplified by her emphasis on the use of technology as a tool of empire. -

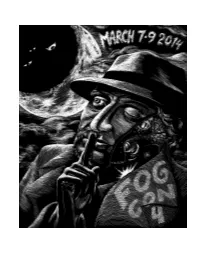

Fogcon 4 Program

Contents Comments from the Chair By Guy W. Thomas 2 Convention Committee 2 Honored Guest Tim Powers By Cliff Winnig 3 Honored Guest Seanan McGuire By Tanya Huff 4 Honored Ghost James Tiptree, Jr. By Jeffrey Smith 5 About Cons – Interviews with some of our guests 6 Everything but the Signature Is Me By James Tiptree, Jr. 10 Hotel 14 Registration 15 Consuite 15 Dealers’ Room 15 Game Room 15 Safety Team 15 Programming, Friday March 7, 2014 17 Programming, Saturday, March 8, 2014 20 Programming, Sunday, March 9, 2014 26 Program Participants 28 Access Information 36 Anti-Harassment Policy 39 Photography Policy 39 FOGcon 4 – Hours and Useful Information Back Cover Editor: Kerry Ellis; Proofreaders: Lynn Alden Kendall, Wendy Shaffer, Guy W. Thomas, Aaron I. Spielman and Debbie Notkin Cover: Art by Eli Bishop; Printed on 30% recycled PCW acid free paper Printed on 100% recycled PCW acid free paper. FOGcon 4 is a project done jointly by Friends of Genre and the Speculative Literature Foundation. Copyright © 2014 FOGcon 4. All Rights Revert to the Authors and Artists. 1 Comments from the Chair By Guy W. Thomas Welcome to FOGcon 4! Once again we bring you the convention by the Bay. FOGcon has always been a convention by and for genre fiction fans. This is our party, our celebration. The theme this year is Secrets. The secret I learned about running conventions from the founder and chair of the first three FOGcons, the radiant and perspicacious Vylar Kaftan is: find cool, talented people who also want to put on a convention and that you like hanging out with anyway. -

Scientifiction 51 Coker 2017-Wi

SCIENTIFICTION New Series #51 SCIENTIFICTION A publication of FIRST FANDOM New Series #51, 1st Quarter 2017 IN MEMORIAM FIRST FANDOM AWARDS (2017) JOHN R. ‘KLON’ NEWELL A ballot is enclosed for members to cast their votes for the First Fandom Awards. (1935 - 2017) Please return ballots before May 15th. The names of the award recipients will be announced during the annual Hugo Awards Ceremony at the 75th Worldcon. IN MEMORIUM We sadly acknowledge the passing of Richard Adams, Carrie Fischer, Klon Newell, Gene Nigra, Berni Wrightson. WORLDCON UPDATE The 75th World SF Convention will be held in Helsinki, Finland, August 9-13. Guests of Honor: John-Henri Holmberg, Klon Newell at Noreascon 4 Nalo Hopkinson, Johanna Sinisalo, Courtesy of Hazel’s Photo Gallery Claire Wendling, Walter Jon Williams. (Photograph by Chaz Boston Baden) For information: http://www.worldcon.fi/ An associate member of First Fandom, Klon Newell was a long-time collector, NASFIC UPDATE SF fan and bookseller at conventions throughout the country for decades, The North American SF Convention will regarded for his big-hearted generosity. take place in San Juan, Puerto Rico, July 6-9. For information, please visit: IN THIS ISSUE https://www.northamericon17.com/ P. 1: Announcements PUBLICATION NOTES P. 2: President’s Message P. 2: Remembering David A. Kyle Thanks to the contributors to this issue: P. 3: The Korshak Collection on Exhibit Chaz Boston Baden, Todd Dashoff, P. 4: Birthdays and Obituaries Mike Glyer, David Langford, Robert P. 6: A New Book about Otto Binder Lichtman, Craig Mathieson, Mary P. 7: Norman F. Stanley’s Donation McCarthy, Christopher M. -

Futurist Fiction & Fantasy

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications -- Department of English English, Department of September 2006 FUTURIST FICTION & FANTASY: The Racial Establishment Gregory E. Rutledge University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Rutledge, Gregory E., "FUTURIST FICTION & FANTASY: The Racial Establishment" (2006). Faculty Publications -- Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications -- Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. C A L L A L O O FUTURIST FICTION & FANTASY The Racial Establishment by Gregory E. Rutledge “I don’t like movies when they don’t have no niggers in ‘em. I went to see, I went to see “Logan’s Run,” right. They had a movie of the future called “Logan’s Run.” Ain’t no niggers in it. I said, well white folks ain’t planning for us to be here. That’s why we gotta make movies. Then we[’ll] be in the pictures.” —Richard Pryor in “Black Hollywood” from Richard Pryor: Bicentennial Nigger (1976) Futurist fiction and fantasy (hereinafter referred to as “FFF”) encompasses a variety of subgenres: hard science fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, sword-and-sorcerer fantasy, and cyberpunk.1 Unfortunately, even though nearly a century has expired since the advent of FFF, Richard Pryor’s observation and a call for action is still viable. -

Nightmare Magazine, Issue 59 (August 2017)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 59, August 2017 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial: August 2017 FICTION The Devil of Rue Moret James Rabb Senbazuru V.H. Leslie The Spook School Nick Mamatas Shift Nalo Hopkinson NONFICTION The H Word: I Need My Pain Gemma Files Book Reviews: August 2017 Terence Taylor AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS James Rabb Nick Mamatas MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks About the Nightmare Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2017 Nightmare Magazine Cover by Chorazin / Adobe Stock Art www.nightmare-magazine.com FROM THE EDITOR Editorial: August 2017 John Joseph Adams | 629 words Welcome to issue fifty-nine of Nightmare. We have original fiction from James Rabb (“The Devil of Rue Moret”) and Nick Mamatas (“ The Spook School”), along with reprints by V.H. Leslie (“Senbazuru”) and Nalo Hopkinson (“Shift”). We also have Gemma Files bringing us the latest installment of our column on horror, “The H Word,” plus author spotlights with our authors, a showcase on our cover artist, and a fiction review from Terence Taylor. John Joseph Adams Books Update Here’s a quick rundown what to expect from John Joseph Adams Books in 2017: In July, we published Carrie Vaughn’s novel, Bannerless—a post-apocalyptic mystery in which an investigator must discover the truth behind a mysterious death in a world where small communities struggle to maintain a ravaged civilization decades after environmental and economic collapse. Here’s what some of the early reviews have been saying about it: “Skillfully portrays a vastly altered future America. [The] focus on sustainability and responsibility is unusual, thought-provoking, and very welcome.” —Publishers Weekly “An intimate post-apocalyptic mystery [. -

Tuesday, March 20, 2012 8:30-11:00 P.M. Pre-Conference Party President’S Suite Open to All

Tuesday, March 20, 2012 8:30-11:00 p.m. Pre-Conference Party President’s Suite Open to all. Refreshments will be served. ******* Wednesday, March 21, 2012 2:30-3:15 p.m. Pre-Opening Refreshment Ballroom Foyer ******* Wednesday, March 21, 2012 3:30-4:15 p.m. Opening Ceremony Ballroom Host: Donald E. Morse, Conference Chair Welcome from the President: Jim Casey Opening Panel: Monstrous Significations Ballroom Moderator: Jim Casey Jeffrey Jerome Cohen China Miéville Kelly Link Veronica Hollinger Gary K. Wolfe ******* Wednesday, March 21, 2012 4:30-6:00 p.m. 1. (SF) The Many Faces of the Black Vampiress: Octavia Butler's Fledgling Pine Chair: Rebekah Sheldon University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee “Shori Matthews has told us the truth”: Unreliable Narration in Octavia Butler's Fledgling. Florian Bast University of Leipzig “Unspeakable Desire:” Interracial Liaisons in Octavia Butler’s Fledgling Marie-Luise Löffler University of Leipzig Monsters and Power: The Construction of Race and Identity in Octavia Butler’s Fledgling Thomas Cassidy South Carolina State University 2. (VPA) Monstrous Comic Books Oak Chair: Daniel Felts University of Memphis The Darkness in the “Dark Phoenix Saga”: Gender, Power, and Identity in the X-Men Gregory Cavenaugh Rollins College “It” All Depends: Complicated Monstrosity in Nightschool: The Weirn Books Lynette James USM Stonecoast Monsters in the Fourth Dimension: The Imaginative Plane of the 3D Comic Book David Steiling Ringling College of Art and Design 3. (FTV) Expressive Monsters: Polanski, Aronofsky, and Soul Eaters Cypress Chair: Mark Bould University of the West of England Dialectical Progression in Roman Polanski's Apartment Trilogy Robert Niemi St. -

Read Excerpt (PDF)

INTRODUCTION My Love Affair with Queer Boys, Gay Lit, and Science Fiction Richard Labonté I can’t recall the first science fiction book I ever read. I know I was reading science fiction by the time I was seven or eight, when I was already bored by the Hardy Boys, the Bobbsey Twins, the Rover Boys, Nancy Drew, Brains Benton, and Tom Swift, whose spacey adventures were my favourite for reading more than once – though I had a thing for those Hardy Boys and their hearty comradeship, too. Perhaps my first time encountering the worlds of “if” was with one of the non-Tarzan books by Edgar Rice Burroughs, when I was eight or nine. Soon I was escaping from the world with The Chessmen of Mars, or exploring forgotten worlds in At the Earth’s Core. I was living then in Paris, a military brat, borrowing English-language books from my father’s enlisted male friends (my parents didn’t read much beyond the daily newspaper). I recall seeing a large shelf of Burroughs books in our neighbour’s living room. I also recall how I liked to wrestle with our neighbour, a single corporal, probably ten years older than me, though he seemed as old as my parents. When I was ten, my father was transferred to Mont Apica, a now-shuttered Pine Tree Line radar station in the isolated middle of Parc des Laurentides in Quebec: the base was small, 800 or so residents, more than sixty kilometres (thirty-five miles) from the nearest small town, a self-contained village, really: I was able 9 10 The Future is Queer to deliver the daily newspaper bussed in from Montreal to about eighty homes during my school lunch break. -

This Is the Final Version of the Program As of February 27, 2011. Any Changes Made After This Point Will Be Reflected in the Errata Sheet

This is the final version of the program as of February 27, 2011. Any changes made after this point will be reflected in the errata sheet. ******* Tuesday, March 15, 2011 7:00 p.m. Pre‐Conference Party President’s Suite Open to all. ******* Wednesday, March 16, 2011 2:30‐3:30 p.m. Pre‐Opening Refreshment Capri ******* Wednesday, March 16, 2011 3:30‐4:15 p.m. Opening Ceremony Capri Host: Donald E. Morse, Conference Chair Welcome from the President: Jim Casey Opening Panel: Science Fiction and Romantic Comedy: Just Not That Into You Capri Moderator: Jim Casey Terry Bisson James Patrick Kelly John Kessel Connie Willis ******* Wednesday, March 16, 2011 4:30‐6:00 p.m. 1. (PCS) Fame, Fandom, and Filk: Fans and the Consumption of Fantastical Music Pine Chair: Elizabeth Guzik California State University, Long Beach Out of this World: Intersections between Science Fiction, Conspiracy Culture and the Carnivalesque Aisling Blackmore University of Western Australia “I’m your biggest fan, I’ll follow you until you love me”: Fame, the Fantastic and Fandom in the Haus of Gaga Daryl Ritchot Simon Fraser University Pop Culture on Blend: Parody and Comedy Song in the Filk Community Rebecca Testerman Bowling Green State University 2. (SF) Biotechnologies and Biochauvinisms Oak Chair: Neil Easterbrook TCU Biotechnology and Neoliberalism in The Windup Girl Sherryl Vint Brock University Neither Red nor Green: Fungal Biochauvinism in Science Fiction Roby Duncan California State University, Dominguez Hills Daniel Luboff Independent Scholar Ecofeminism, the Environment,