Governing Greater Victoria: the Role of Elected Officials and Shared Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sustainable Development Strategy for the District of Sooke – July 2008

A SSUSTAINABLE DDEVELOPMENT SSTRATEGY FOR THE DDISTRICT OF SSOOKE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.................................................................................................... 3 A COMMUNITY AT A THRESHOLD OF THE 21ST CENTURY.................................................. 3 THE ROLE OF THIS STRATEGY .......................................................................................... 4 CONTROL OVER CHANGE................................................................................................... 5 EIGHT PILLARS OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT............................................................. 5 CREATING THIS STRATEGY................................................................................................ 5 A SHARED VISION FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE.............................................................. 6 PRIORITIES......................................................................................................................... 6 Strategy #1: Create neighbourhood centres and a downtown waterfront that are compact and complete.................................................................... 8 Strategy #2: Develop a transportation system that provides viable opportunities for non-automobile transportation and transit use. ......... 11 Strategy #3: Support low-impact, energy-efficient, healthy buildings in which to live, work and play. ...................................................................... 15 Strategy #4: Celebrate cultural and ecological assets through the management -

Order in Council 42/1934

42 Approved and ordered this 12th day/doff January , A.D. 19 34 Administrator At the Executive Council Chamber, Victoria, arm~ame wane Aar. PRESENT: The Honourable in the Chair. Mr. Hart Mr. Gray Mn '!actersJn Mn !...acDonald Mn Weir Mn Sloan Mn ?earson Mn To His Honour strata r The LieLIRtneaftCOMPOtTrae in Council: The undersigned has the honour to recommend that, under the provisions of section 11 of the " Provincial Elections Act," the persons whose names appear hereunder be appointed, without salary, Provincial Elections Commissioners for the purposes of the said section 11 for the Electoral Districts in which they reside respectively, as follows :— ELECTORAL DISTRICT. NAME. ADDRESS. ESQUIMA IT Pilgrim, Mrs. Jemima Jane 1253 Woodway Ave.,Esquimall wins, John William Sooke Doran, John Patrick R.R. 2, Sooke Wilson, Albert Leslie Sooke Robinson, Robert William Colwood Yates, James Stuert Langford Wale, Albert Edward Langford Trace, John Luxton, via Colwood Field, Chester Gibb Metchosin Hearns, Henry 936 Craigflower Rd., Esq. Fraser, Neil 1264 Old Esquimalt Rd.,Esq. Hodgson, William 1219 Carlisle St., Mesher, James Frederick 1553 Esquimalt Rd., " Nicol, Mrs. Margaret 1411 Esquimalt Rd., " Clark, Mrs. Christina Jane Stuart Shirley, R.R.2, Sooke Alsdorf, Mrs. Katharine Iri s,Cobble Hill Barry, Mrs. Letitia Rosa Cobble Hill Barry, Tierney Patrick Cobble Hill Meiillan, Mrs. Barbara Ann Cobble Hill Dick, Robert Shawnigan Lake Havers, Arthur Robert Shawnigan Lake Garnett, George Grant Cobble Hill Dougan, Stephen David Cobble Hill Walker, Lady Emily Mary 649 Admirals Rd.,Esquimalt Walker, Eric Henry James 649 Admirals Rd.,Esquimalt Walker, William Ure Jordan River Brown, Mrs. -

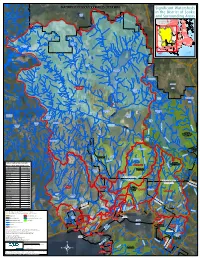

Significant Watersheds in the District of Sooke and Surrounding Areas

Shawnigan Lake C O W I C H A N V A L L E Y R E G I O N A L D I S T R I C T Significant Watersheds in the District of Sooke Grant Lake and Surrounding Areas North C o w i c h a n V a l l e y Saanich R e g i o n a l D i s t r i c t Sidney OCelniptrahl ant Lake Saanich JdFEA H a r o S t r a Highlands it Saanich View Royal Juan de Fuca Langford Electoral Area Oak Bay Esquimalt Jarvis Colwood Victoria Lake Sooke Weeks Lake Metchosin Juan de Fuca Electoral Area ca SpectaFcu le Lake e d it an ra STUDY Ju St AREA Morton Lake Sooke Lake Butchart Lake Devereux Sooke River Lake (Upper) Council Lake Lubbe Wrigglesworth Lake Lake MacDonald Goldstream Lake r Lake e iv R e k o Bear Creek o S Old Wolf Reservoir Boulder Lake Lake Mavis y w Lake H a G d Ranger Butler Lake o a l n d a s Lake Kapoor Regional N C t - r i a s Forslund Park Reserve e g n W a a a o m r l f C r a T Lake r e R e k C i v r W e e e r a k u g h C r e Mount Finlayson e k Sooke Hills Provincial Park Wilderness Regional Park Reserve G o ld s Jack t re a Lake m Tugwell Lake R iv e r W augh Creek Crabapple Lake Goldstream Provincial Park eek Cr S ugh o Wa o Peden k Sooke Potholes e Lake C R Regional Park h i v a e Sheilds Lake r r t e r k e s re C ne i R ary V k M e i v e r e r V C Sooke Hills Table of Significant Watersheds in the e d i t d c Wilderness Regional h o T Charters River C Park Reserve District of Sooke and Surrounding Areas r e e k Watershed Name Area (ha) Sooke Mountain Sooke River (Upper) 27114.93 Boneyard Provincial Park Lake DeMamiel Creek 3985.29 Veitch Creek 2620.78 -

Cowichan Valley Trail Brochure (2021)

FLIP FOR MAP FOR FLIP treaded tires are highly recommended. recommended. highly are tires treaded Kinsol Trestle. Surface conditions vary so cyclists should note that that note should cyclists so vary conditions Surface Trestle. Kinsol reconnects with your start point in Duncan. Duncan. in point start your with reconnects south through forests and rural farmland before arriving at the Historic Historic the at arriving before farmland rural and forests through south Ganges. Catch another ferry from Vesuvius to Crofton and a short ride ride short a and Crofton to Vesuvius from ferry another Catch Ganges. Glenora Trails Head Park on Robertson Road. The trail route travels travels route trail The Road. Robertson on Park Head Trails Glenora from Swartz Bay, the route meanders along roads to the village of of village the to roads along meanders route the Bay, Swartz from This popular cycling and equestrian route starts and finishes at at finishes and starts route equestrian and cycling popular This Difficulty: Difficulty: Saanich Peninsula. After a quick ferry connection to Saltspring Island Island Saltspring to connection ferry quick a After Peninsula. Saanich Easy Distance: Distance: before connecting with the Lochside Trail and heading north up the the up north heading and Trail Lochside the with connecting before 26 km return km 26 ROUTE B — Glenora Trails Head Park to Kinsol Trestle Kinsol to Park Head Trails Glenora — B ROUTE route continues on the Galloping Goose Regional Trail into Victoria Victoria into Trail Regional Goose Galloping the on continues route dropping into Langford, along the Sooke Hills Wilderness Trail. The The Trail. -

Sooke + Nanaimo

SOOKE + NANAIMO DAY 1 Full-day in Sooke Take a 90-minute ferry sailing on the MV Coho from Port LUNCH Jordan River Angeles, WA to downtown Victoria, BC. Depart downtown AFTERNOON Victoria and drive approximately 2 hours on the Pacific Marine • China Beach Take a short walk to the western end of the beach Circle Route to Soule Creek Lodge in Port Renfrew. to the waterfall or wander at length to the east. Approximate hiking time: 30 minutes round-trip. FIRST NIGHT + NEXT DAY BREAKFAST • Soule Creek Lodge in Port Renfrew Perched high on the San • French Beach A wide swatch of green lawn fronts this sand and Juan Ridge with 360 degree panoramic views of the Pacific pebble beach where visitors can relax and enjoy a picnic or take a Ocean and 160 private acres filled with wildlife. Enjoy ocean-view cool dip in the ocean. accommodation in a lodge suite, yurt, or cabin with a wonderful Approximate hiking time: 15 minutes round-trip. hot breakfast included with your stay. • Whiffin Spit A natural breakwater just south of Sooke which is part of the Quimper Park. It is the perfect spot to sit back and SUGGESTED MORNING ACTIVITIES take in the beautiful Juan de Fuca Strait and the Sooke Basin. • Avatar Grove A phenomenal stand of giant old-growth red cedar and Douglas fir alongside the Gordon River within the traditional DINNER territory of the Pacheedaht First Nation. Beautiful fern-draped • Stone Pipe Grill Made Fresh, Made Here. Cheesecake, soup, creeks with moss-covered rocks and small waterfalls meander burgers, fries, and sauces are all made on site. -

Sooke, Port Renfrew, Nanaimo + Tofino

SOOKE, PORT RENFREW, NANAIMO + TOFINO DAY 1 LUNCH 17 Mile House Pub Seventeen miles from Victoria City Hall, this TRANSPORTATION pub has retained its yesterday charm. There is even a hitching post Take the scenic 90-minute morning sailing on the MV Coho from for visitors arriving by horseback. Creative West Coast fare and Port Angeles, WA to downtown Victoria, BC. local seafood can be enjoyed looking out over the garden or next to Follow along a portion of the rugged Pacific Marine Circle Route the crackling fire. from downtown Victoria to Sooke, Port Renfrew, and Lake Cowichan Stickleback West Coast Eatery The true West Coast, with a nat- on your way to Nanaimo. This coast to coast journey of Vancouver ural cedar bar, a stunning mural of Sombrio Beach and great food! Island offers panoramic views of the Juan de Fuca Strait. Enjoy a The menu offers everything from house-made burgers and wraps to quieter way of life while visiting spectacular provincial parks and pasta and baby back ribs. pastoral landscapes. AFTERNOON ACTIVITY SUGGESTIONS Please Note: This is a remote route with limited services. Some • Sooke Coastal Explorations Invigorating salt-filled ocean air sections may be narrow and sharp, and driving times may vary and ever-changing seascapes are the backdrop for this eco- depending on the type of vehicle. Please exercise caution while driving. adventure tour. Take an exhilarating boat ride that will leave you Depart downtown Victoria and enjoy a leisurely 40-minute drive with a deep appreciation for the enchanting creatures that to Sooke along the southern coast of Vancouver Island. -

Tsunami Notification Zone D for British Columbia "

" Tsunami Notification Zone D for British Columbia " NANAIMO " Gabriola Island Snuneymuxw GREATER VANCOUVERCommunities REGIONAL within DISTRICT (648) Tsunami Notification Zone D Delta!. Harmac Cedar Capital Regional District Beecher Bay North Saanich SookeLadner Central Saanich Oak Bay Tsawout NANAIMO REGIONAL DISTRICT Colwood Saanich T'Souke Esquimalt Shirley Victoria Valdes Island Jordan River Sidney View Royal Metchosin Songhees Lyackson (646) Tsawwassen Thetis Island Ladysmith ! Stuart Channel Strait of Georgia Kuper Saltair Island Trincomali Channel Chemainus Stz'uminus Galiano Island Halalt (645) Mayne Island Prevost Island Saltspring Island Tumbo Island North Pender Saturna Island Island Duncan " Cowichan (642) South Pender Island COWICHAN VALLEY REGIONAL DISTRICT Cowichan Bay V a n c o u v e r Boundary Pass I s l a n d Tseycum (655) ! O! Sidney Saanich Mill Bay North Inlet Saanich ! Malahat (647) Pauquachin (652) Tsawout (654) Tsartlip (653) E Central Haro Strait Saanich USA District of CAPITAL REGIONAL DISTRICT Highlands !. Saanich C View Sombrio Pt Royal Esquimalt Juan de Fuca Provincial Park Oak Langford ! (644) ! Bay Songhees Magdelena Pt (656) " COLWOOD O! VICTORIA San Simeon Pt China Beach T'Sou-ke (657) Metchosin Sooke French Beach !. East Sooke Beecher Bay Otter Pt (640) National Tsunami Warning Center (NTWC) Breakpoint BC - Washington Border British Columbia, Canada Washington, United States of America © Juan de Fuca Strait D USA Tsunami Notification Zones Notifications B.C. Tsunami Notification Zones Legend Alert Level Threat Action " City O! Tide Gauge ZONE A - THE NORTH COAST AND HAIDA GWAII !. District Municipality Parks A Inundating wave possible Full evacuation suggested Tsunamis are rare but serious events. Many areas of coastal B.C. -

Business Case

Business Case MARCH 9, 2017 FINAL BUSINESS CASE Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... I 1.1 RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................................................... II ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................ III GLOSSARY ......................................................................................................................................V 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 PROJECT SCOPE................................................................................................................ 1 1.1.1 Subsequent Considerations ...........................................................................2 1.2 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................. 2 1.3 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATI ON........................................................................................ 3 2.0 PROJECT PROCESS ............................................................................................................ 4 2.1 ANALYSIS FRAMEWORK .................................................................................................... 4 2.2 DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL STUDY................................................................................... -

Aquifers of the Capital Regional District

Aquifers of the Capital Regional District by Sylvia Kenny University of Victoria, School of Earth & Ocean Sciences Co-op British Columbia Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection Prepared for the Capital Regional District, Victoria, B.C. December 2004 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Kenny, Sylvia. Aquifers of the Capital Regional District. Cover title. Also available on the Internet. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-52651 1. Aquifers - British Columbia - Capital. 2. Groundwater - British Columbia - Capital. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. II. University of Victoria (B.C.). School of Earth and Ocean Sciences. III. Capital (B.C.) IV. Title. TD227.B7K46 2004 333.91’04’0971128 C2004-960175-X Executive summary This project focussed on the delineation and classification of developed aquifers within the Capital Regional District of British Columbia (CRD). The goal was to identify and map water-bearing unconsolidated and bedrock aquifers in the region, and to classify the mapped aquifers according to the methodology outlined in the B.C. Aquifer Classification System (Kreye and Wei, 1994). The project began in summer 2003 with the mapping and classification of aquifers in Sooke, and on the Saanich Peninsula. Aquifers in the remaining portion of the CRD including Victoria, Oak Bay, Esquimalt, View Royal, District of Highlands, the Western Communities, Metchosin and Port Renfrew were mapped and classified in summer 2004. The presence of unconsolidated deposits within the CRD is attributed to glacial activity within the region over the last 20,000 years. Glacial and glaciofluvial modification of the landscape has resulted in the presence of significant water bearing deposits, formed from the sands and gravels of Capilano Sediments, Quadra and Cowichan Head Formations. -

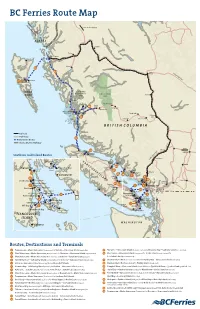

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver -

Bedrock Geology of the North Saanich-Cobble Hill Area, British Columbia, Canada

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF John Michael Kachelmeyer for the degree ofMaster of Science in Geology presented on May 30, 1978 Title: BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF THE NORTHSAANICH-COBBLE HILL AREAS, BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy Keith F./Oles The bedrock of the North Saanich-Cobble Hill areas consists of igneous and sedimentary rocks of Early Jurassic through Late Cretaceous age.Early Jurassic andesitic Bonanza Volcanics are intruded by Middle Jurassic Saanich Granodiorite plutonic rocksand dikes.Late Cretaceous Nanaimo Group clastic rocksnonconformably overlie these Jurassic units.The four oldest formations of the group (Comox, Has lam, Extension-Protection, and Cedar District) are exposed within the study area. The Nanaimo Group formations were deposited within a subsid- ing marine basin (the Nanaimo Basin) located to the east ofsouthern Vancouver Island.Uplift of pre-Late Cretaceous basement rocks on Vancouver Island to the west and on mainland British Columbia tothe east of the basin created rugged, high-relief source areasthat were chemically weathered in a warm tropical climate and mechanically eroded by high-energy braided stream systems. The Comox and Has lam sediments were deposited in response to a continual transgression of a Late Cretaceous seaway overthis rugged terrain.Braided stream systems trending north-northwest into the basin deposited Comox (Benson Member) gravelsand sands onto a high-energy, cliffed shoreline.Erosion of the highlands and transgression of the marine seaway resulted in subduedtopographic relief and the deposition of sediments by low-energymeandering streams within a river traversed coastal plain, followedby silt and clay deposition in tidal flat and lagoonal environments,and finally by sand deposition in a higher energy barrier bar environment.Contin- ued marine transgression resulted in the depositionof massive marine mudstones and cyclic sandstone to mudstone sequencesof the Has lam Formation. -

Greater Victoria & Region Greater Victoria & Region

Galiano Island Greater Greater Mayne Victoria Island Salt Spring Island Saturna North Island & Region S Pender & Region D N A Island L S For more detailed I F L U 5 59 G maps, see pages 8– . D N A R South E V U Pender O C The Gulf Islands N Island A V O T Saanich Peninsula & Sidney Victoria, Saanich, Esquimalt & Oak Bay S A BC Ferries – WestShore, Colwood, Langford, Highlands, 1 NORTH Swartz Bay View Royal & Metchosin A SAANICH Ferry Terminal N I Sooke & Port Renfrew Mill C Bay H I TO SA N JUAN I N 2 SLA ND AND SIDNEY ANA T COR L Victoria TES LEGEND: R A Gulf Islands N E International S National Park - Airport C T Highway A Reserve N A D A Main Road UNITED STATES H W Y John Dean 17 Ferry Route . Provincial Sidney CANADA Park James Island Park Island CENTRAL Ferry Terminal Brentwood SAANICH Bay Island View Victoria Int’l Airport Beach Park P Full-Service Seaplane A M T R B Terminal A A S Y T N H W Helijet Terminal O R Y S Gowlland Tod . Y Provincial A A Mount Work I L Park Sooke T N Regional Elk I Lake F Park Lake 17A O 1 F HIGHLANDS Cordova Bay Beaver Elk/Beaver G Lake Lake E Regional O VIEW Park R ROYAL G N I Francis Mt. Douglas A King Park Regional Goldstream Thetis Lake Park SAANICH Provincial Regional Park Park University r 17 of Victoria e v i R Sooke Mount W E Potholes 1A WESTSHORE Tolmie Provincial Park Cadboro-Gyro Park LANGFORD Royal Roads VICTORIA Park .