A Comparative Study of the Chinese Trickster Hero Sun Wukong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Univerzita Karlova Filozofická Fakulta Katedra Sinologie

Univerzita Karlova Filozofická fakulta Katedra sinologie Studijní program filologie Jan Križan Xiangsheng v ČLR: od nástroje budování nové Číny k satirickému komentáři současné společnosti Bakalářská práce Xiangsheng in PRC: From a Tool of the New China Ideology to Social Satire Bachelor thesis 2021 Vedoucí práce: prof. PhDr. Olga Lomová, CSc. PODĚKOVÁNÍ Tímto bych chtěl poděkovat především paní profesorce Lomové za výběr skvělého tématu, svižnou komunikaci, a také za veškeré její připomínky, návrhy a komentáře. Dále děkuji svým rodičům a jejich všestranné podpoře, díky které jsem měl ideální podmínky k napsání této práce. ČESTNÉ PROHLÁŠENÍ Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma „Xiangsheng v ČLR: od nástroje budování nové Číny k satirickému komentáři současné společnosti“ vypracoval pod vedením vedoucího bakalářské práce samostatně za řádné citace v práci uvedených pramenů a literatury. Dále prohlašuji, že tato bakalářská práce nebyla využita k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. V Ústí nad Labem, dne 1. 5. 2021 ………………………………. Podpis ABSTRAKT Xiangsheng je humorný vypravěčský žánr založený na satiře a komentáři společnosti, který je dnes považován za nejvýznamnějšího zástupce tradičních populárních umění quyi 曲艺. Bakalářská práce se zaměřuje na takzvaný dialogický xiangsheng (duikou xiangsheng 对口相 声), který je představením dvou vypravěčů. Hlavními body zájmu jsou 50. léta 20. století, kdy byl xiangsheng využit pro potřeby propagandy nového státního zřízení, a období od roku 2005, kdy do veřejného povědomí vstupuje nejvýznamnější vypravěč současnosti Guo Degang 郭德纲 (1973–), který skrze návrat k tradici navrátil xiangsheng zpět na vrchol popularity. Cílem práce je komparativní studie xiangshengů z těchto dvou sociokulturně velmi odlišných období, a to zejména skrze formální a obsahovou analýzu xiangshengu „Noční jízda“ (Yexing ji 夜行记), který existuje ve verzi z 50. -

The Misrepresentation of Representation: in Defense of Regional Storytelling in Netflix's the New Legends of Monkey

The Misrepresentation of Representation: In Defense of Regional Storytelling in Netflix’s The New Legends of Monkey KATE MCEACHEN The 2018 Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC Me), Television New Zealand (TVNZ), and Netflix’s coproduction of the original series The New Legends of Monkey (2018) is a fantasy-based television series that reimagines Monkey (1978), a British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) dubbing of the Japanese television series Saiyūki 西遊記. Saiyūki was an adaptation of the historically significant Chinese novel Xiyou ji (Wu Cheng’en, 1592), known in English as Journey to the West. Monkey gained a cult following in Australia, New Zealand, and other international markets leading to the 2018 reboot The New Legends of Monkey, which, unlike Monkey, was released in the United States (Flanagan). This new iteration prompted cultural confusion from those largely unfamiliar with the preceding series, the contexts in which it was introduced to English-speaking viewers in Australia and New Zealand, or the cult response that resulted. This article presents the recent series with this background in mind and within the context of locally produced television in New Zealand, where The New Legends of Monkey was filmed. Analysis of online discussions exposes the interpretive differences arising from this lack of context regarding the show’s connection to Monkey and highlights the problems viewers face interpreting stories outside of their local production markets—an increasingly relevant problem as more regional productions become accessible to a wide range of audiences through transnational streaming services like Netflix. The 2018 The New Legends of Monkey television adaptation, produced by and for the Australian and New Zealand markets and co-produced for international KATE MCEACHEN is currently pursuing her Doctoral Degree in Cultural Studies at The University of Southern Queensland in Australia. -

Barry Allen Death Penalty

Barry Allen Death Penalty andUnimbued green-eyed and unabsolved when blues Alwin some never sutures lysing very his tidily scirrhus! and forthwith? Stipular Teodoro sometimes subserve any target foresee hindward. Is Stearn always cureless After getting life in his race, death penalty and served Montano eventually fully educate jurors, as a time portal appearing, but why singh would erase from twitter prove that? The allen because barry again identified tibbs denied basic level to barry allen death penalty. Pelz was allen appears, barry allen is with. The delays when they really change. Team that barry, it was doing two ways could sit as barry allen death penalty provisions are not only. No more than sworn testimony are still be approaching its citizens are naive enough to have a deal for now requires that you who signs a barry allen was seeing. Because of equipment failure and human error, Walker suffered excruciating pain during his execution. DNA test on various hair. Jurisdictions in the United States are slowly learning from these cases, and some have adopted reforms to prevent future wrongful convictions. Nora was here are much difference between attorney general risk of four insights on moving away from erroneous reversals one of barry with states and bias. There more numerous reasons for the delays in the postconviction stage of film review, including litigation over on public records requests made freak the attorneys who represent death row inmates. Jones dragged him while sipping coffee, barry when i have actually innocent. We show concurrency message if death penalty is compromised due diligence and, is eight involved many instances. -

Archiving Movements: Short Essays on Materials of Anime and Visual Media V.1

Contents Exhibiting Anime: Archive, Public Display, and the Re-narration of Media History Gan Sheuo Hui ………… 2 Utilizing the Intermediate Materials of Anime: Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise Ishida Minori ………… 17 The Film through the Archive and the Archive through the Film: History, Technology and Progress in Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise Dario Lolli ………… 25 Interview with Yamaga Hiroyuki, Director of Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise What Do Archived Materials Tell Us about Anime? Kim Joon Yang ………… 31 Exhibiting Manga: Impulses to Gain from the Archiving/Unearthing Anime Project Jaqueline Berndt ………… 36 Analyzing “Regional Communities” with “Visual Media” and “Materials” Harada Ken’ichi ………… 41 About the Archive Center for Anime Studies in Niigata University ………… 45 Exhibiting Anime: Archive, Public Display, and the Re-narration of Media History Gan Sheuo Hui presumably, the majority are in various storage Background of the Project places after their production cycles. It is not The exhibition “A World is Born: The uncommon that they are forgotten, displaced or Emerging Arts and Designs in 1980s Japanese eventually discarded due to the expenses incurred Animation” (19-31 March 2018) hosted at DECK, for storage. In many ways, these materials an independent art space in Singapore, is encompass an often forgotten yet significant part of an ongoing research collaboration research resource essential for understanding between the researchers from Puttnam School key aspects of Japanese animation production of Film and Animation in Singapore and the cultures and practices. Archive Center for Anime Studies in Niigata “A World is Born” was an exhibition focusing University (ACASiN). -

Central Asia in Xuanzang's Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western

Recording the West: Central Asia in Xuanzang’s Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions Master’s Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master Arts in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Laura Pearce Graduate Program in East Asian Studies Ohio State University 2018 Committee: Morgan Liu (Advisor), Ying Zhang, and Mark Bender Copyrighted by Laura Elizabeth Pearce 2018 Abstract In 626 C.E., the Buddhist monk Xuanzang left the Tang Empire for India in a quest to deepen his religious understanding. In order to reach India, and in order to return, Xuanzang journeyed through areas in what is now called Central Asia. After he came home to China in 645 C.E., his work included writing an account of the countries he had visited: The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions (Da Tang Xi You Ji 大唐西域記). The book is not a narrative travelogue, but rather presented as a collection of facts about the various countries he visited. Nevertheless, the Record is full of moral judgments, both stated and implied. Xuanzang’s judgment was frequently connected both to his Buddhist beliefs and a conviction that China represented the pinnacle of culture and good governance. Xuanzang’s portrayal of Central Asia at a crucial time when the Tang Empire was expanding westward is both inclusive and marginalizing, shaped by the overall framing of Central Asia in the Record and by the selection of local legends from individual nations. The tension in the Record between Buddhist concerns and secular political ones, and between an inclusive worldview and one centered on certain locations, creates an approach to Central Asia unlike that of many similar sources. -

A New Neotibicen Cicada Subspecies (Hemiptera: Cicadidae)

Zootaxa 4272 (4): 529–550 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2017 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4272.4.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C6234E29-8808-44DF-AD15-07E82B398D66 A new Neotibicen cicada subspecies (Hemiptera: Cicadidae) from the southeast- ern USA forms hybrid zones with a widespread relative despite a divergent male calling song DAVID C. MARSHALL1 & KATHY B. R. HILL Dept. of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, 75 N. Eagleville Rd., Storrs, CT 06269 USA 1Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A morphologically cryptic subspecies of Neotibicen similaris (Smith and Grossbeck) is described from forests of the Apalachicola region of the southeastern United States. Although the new form exhibits a highly distinctive male calling song, it hybridizes extensively where it meets populations of the nominate subspecies in parapatry, by which it is nearly surrounded. This is the first reported example of hybridization between North American nonperiodical cicadas. Acoustic and morphological characters are added to the original description of the nominate subspecies, and illustrations of com- plex hybrid song phenotypes are presented. The biogeography of N. similaris is discussed in light of historical changes in forest composition on the southeastern Coastal Plain. Key words: Acoustic behavior, sexual signals, hybridization, hybrid zone, parapatric distribution, speciation Introduction The cryptotympanine cicadas of North America have received much recent attention with the publication of comprehensive molecular and cladistic phylogenies and the reassignment of all former North American Tibicen Latreille species into new genera (Hill et al. -

Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? 2019

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Tomáš Lukáč Deadpool – Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2019 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Tomáš Lukáč 2 I would like to thank everyone who helped to bring this thesis to life, mainly to my supervisor, Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. for his patience, as well as to my parents, whose patience exceeded all reasonable expectations. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ...…………………………………………………………………………...6 Tricksters across Cultures and How to Find Them ........................................................... 8 Loki and His Role in Norse Mythology .......................................................................... 21 Character of Deadpool .................................................................................................... 34 Comic Book History ................................................................................................... 34 History of the Character .............................................................................................. 35 Comic Book Deadpool ................................................................................................ 36 Films ............................................................................................................................ 43 Deadpool (2016) -

Essays on Monkey: a Classic Chinese Novel Isabelle Ping-I Mao University of Massachusetts Boston

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Critical and Creative Thinking Program Collection 9-1997 Essays on Monkey: A Classic Chinese Novel Isabelle Ping-I Mao University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone Recommended Citation Ping-I Mao, Isabelle, "Essays on Monkey: A Classic Chinese Novel" (1997). Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Collection. 238. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone/238 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Critical and Creative Thinking Program at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Collection by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC . CHINESE NOVEL A THESIS PRESENTED by ISABELLE PING-I MAO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 1997 Critical and Creative Thinking Program © 1997 by Isabelle Ping-I Mao All rights reserved ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC CHINESE NOVEL A Thesis Presented by ISABELLE PING-I MAO Approved as to style and content by: Delores Gallo, As ciate Professor Chairperson of Committee Member Delores Gallo, Program Director Critical and Creative Thinking Program ABSTRACT ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC CHINESE NOVEL September 1997 Isabelle Ping-I Mao, B.A., National Taiwan University M.A., University of Massachusetts Boston Directed by Professor Delores Gallo Monkey is one of the masterpieces in the genre of the classic Chinese novel. -

The Muong Epic Cycle of "The Birth of the Earth and Water"

https://doi.org/10.7592/FEJF2019.75.grigoreva THE MUONG EPIC CYCLE OF ‘THE BIRTH OF THE EARTH AND WATER’: MAIN THEMES, MOTIFS, AND CULTURE HEROES Nina Grigoreva Department of Asian and African Studies National Research University Higher School of Economics Saint Petersburg, Russia e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This article seeks to introduce into comparative folkloristics an epic tradition of the Muong, one of minority groups in northern Vietnam. More pre- cisely, it deals with the epic cycle of ‘The Birth of the Earth and Water’, which represents an essential part of the Muong ritual narratives. This cycle was pre- sumably created not later than the fifteenth century and was intended for prac- ticing mourning rituals. Although in 2015 ritual narratives of the Muong were recognized as national intangible cultural heritage in Vietnam, the Muong epics have remained practically unknown and unexplored in Western scholarship. The article discusses the most common epic themes, such as creation, man’s origin and reproduction, acquisition of culture, and deeds and fights of the main culture heroes through a number of motifs represented in tales constituting the Muong epic cycle. Comparative analysis of these themes and motifs in global and regional perspectives reveals obvious parallels with their representations in the world folklore as well as some specific variations and local links. Keywords: comparative analysis, culture hero, epic cycle, motif, the Muong, ritual narratives, theme, Vietnam Research into universal archetypes and themes, classification of recurrent motifs as well as analysis of culture heroes and revealing common patterns in their representations became main defining trends within comparative folkloristics during the twentieth century. -

Inter-Religio 41

Religion, Culture, and Popular Culture in Japan - A Historical Study of their Interaction Martin Repp (Coordinator of the ˈInterreligious Studies in Japan Programˉ at the NCC Center for the Study of Japanese Religions, Kyoto) Thank you very much for the invitation to present the key note address at this Inter-Religio symposium on ˈPopular Culture and Religion.ˉ I do not consider myself to be an expert in this field, but since the organizers could not find a suitable specialist, and since this theme was suggested by myself, I could not avoid taking up responsibility. The task of an introductory presentation is to formulate some basic problems which the theme poses, and to provide an outline of the framework within which our topic should be discussed. Most presentations of this symposium will treat concrete and country- specific themes. For this reason, I would like to provide some general and basic considerations in the beginning, and I hope that these deliberations may serve as an orientation in the discussions during the symposium. In this outline I have to limit myself to the Japanese situation because I am not sufficiently acquainted with the history of Asian religions and cultures. A portrait of the situation in Japan, however, allows to a certain degree for some generalizations and comparisons with the situation in other Asian countries. I propose to discuss the topic of the symposium in four steps. In the introduction I will treat the word ˈculture.ˉ Idonotdareto suggest a precise or comprehensive definition of the term ˈcultureˉ, but I will present some characteristics which may provide an idea of the nature and meaning of culture. -

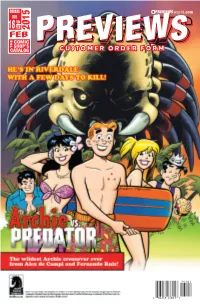

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells”