Legal Frameworks for Hacking by Law Enforcement: Identification, Evaluation and Comparison of Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

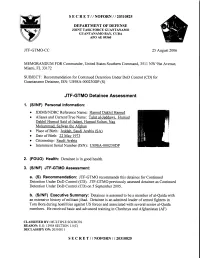

JTF-GTMO Detainee Assessment

S E C R E T //NOFORN I I 20320619 DEPARTMENTOF DEFENSE HEADQUARTERS,JOINT TASK FORCEGUANTANAMO U.S. NAVAL STATION,GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA APO AE 09350 JTF-GTMO-CDR 19June 2007 MEMORANDUM FOR Commander,United StatesSouthem Command. 3511 NW 9lst Avenue. Miami,FL33172. SUBJECT: Recommendationfor ContinuedDetention Under DoD Control (CD) for GuantanamoDetainee, ISN: US9SA-000079DP(S) JTF-GTMO DetaineeAssessment 1. (S//NF) Personal Information: o JDIMSAIDRC ReferenceName: FahedA al-Harasi o Aliases and Current/True Name: Fahd Atiyah Hamza Hamid al-Harazi" Hassanal-Makki. FahedFahad" Khalid. Abu Hassan. al-Sharif. Abu Barak o Placeof Birth: Mecca. SaudiArabia (SA) o Date of Birth: 18 November 1978 o Citizenship: SaudiArabia o InternmentSerial Number (ISN): US9SA-000079DP 2. (U//T'OUO) Health: Detaineeis in good health. 3. (S//NF) JTF-GTMO Assessment: a. (S) Recommendation: JTF-GTMO recommendsthis detaineefor ContinuedDetention Under DoD Control (CD). JTF-GTMO previouslyassessed detainee for Continued Detentionwith TransferLanguage on 26May 2006. b. (S//NF) Executive Summary: Detaineeis reportedto be a memberof al-Qaida. He was identified as having attendedmilitant training and was an instructor at the al-Qaida al- Faruq Training Camp. Detaineewas in Afghanistan (AF) since 1999 during which he is assessedto have participated in hostilities againstUS and Coalition forces as a member of Classifiedby: MultipleSources REASON:E.O. 12958, AS AMENDED,Section 1.4(C) Declassi$on:20320619 S E C R E T //NOFORN I I 20320619 S E C R E T // NOFORN I I 20320619 JTF-GTMO.CDR SUBJECT: Recommendationfor ContinuedDetention Under DoD Control (CD) for GuantanamoDetainee, ISN: US9SA-000079DP(S) UsamaBin Laden's (UBL) 55th Arab Brigade.l Detainee'sname and aliaswere listed in recovereddocuments associated with al-Qaida, and the Saudi Ministry of Interior General Directorate of Investigations(Mabahith) identified him as a high priority detainee. -

Inside Russia's Intelligence Agencies

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES Mark Galeotti For his birthday in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was treated to an exhibition of faux Greek friezes showing SUMMARY him in the guise of Hercules. In one, he was slaying the • Russia’s intelligence agencies are engaged in an “hydra of sanctions”.1 active and aggressive campaign in support of the Kremlin’s wider geopolitical agenda. The image of the hydra – a voracious and vicious multi- headed beast, guided by a single mind, and which grows • As well as espionage, Moscow’s “special services” new heads as soon as one is lopped off – crops up frequently conduct active measures aimed at subverting in discussions of Russia’s intelligence and security services. and destabilising European governments, Murdered dissident Alexander Litvinenko and his co-author operations in support of Russian economic Yuri Felshtinsky wrote of the way “the old KGB, like some interests, and attacks on political enemies. multi-headed hydra, split into four new structures” after 1991.2 More recently, a British counterintelligence officer • Moscow has developed an array of overlapping described Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) as and competitive security and spy services. The a hydra because of the way that, for every plot foiled or aim is to encourage risk-taking and multiple operative expelled, more quickly appear. sources, but it also leads to turf wars and a tendency to play to Kremlin prejudices. The West finds itself in a new “hot peace” in which many consider Russia not just as an irritant or challenge, but • While much useful intelligence is collected, as an outright threat. -

CIA Best Practices in Counterinsurgency

CIA Best Practices in Counterinsurgency WikiLeaks release: December 18, 2014 Keywords: CIA, counterinsurgency, HVT, HVD, Afghanistan, Algeria, Colombia, Iraq, Israel, Peru, Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka, Chechnya, Libya, Pakistan, Thailand,HAMAS, FARC, PULO, AQI, FLN, IRA, PLO, LTTE, al-Qa‘ida, Taliban, drone, assassination Restraint: SECRET//NOFORN (no foreign nationals) Title: Best Practices in Counterinsurgency: Making High-Value Targeting Operations an Effective Counterinsurgency Tool Date: July 07, 2009 Organisation: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Author: CIA Office of Transnational Issues; Conflict, Governance, and Society Group Link: http://wikileaks.org/cia-hvt-counterinsurgency Pages: 21 Description This is a secret CIA document assessing high-value targeting (HVT) programs world-wide for their impact on insurgencies. The document is classified SECRET//NOFORN (no foreign nationals) and is for internal use to review the positive and negative implications of targeted assassinations on these groups for the strength of the group post the attack. The document assesses attacks on insurgent groups by the United States and other countries within Afghanistan, Algeria, Colombia, Iraq, Israel, Peru, Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka, Chechnya, Libya, Pakistan and Thailand. The document, which is "pro-assassination", was completed in July 2009 and coincides with the first year of the Obama administration and Leon Panetta's directorship of the CIA during which the United States very significantly increased its CIA assassination program at the -

Wikileaks and the Institutional Framework for National Security Disclosures

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL PATRICIA L. BELLIA WikiLeaks and the Institutional Framework for National Security Disclosures ABSTRACT. WikiLeaks' successive disclosures of classified U.S. documents throughout 2010 and 2011 invite comparison to publishers' decisions forty years ago to release portions of the Pentagon Papers, the classified analytic history of U.S. policy in Vietnam. The analogy is a powerful weapon for WikiLeaks' defenders. The Supreme Court's decision in the Pentagon Papers case signaled that the task of weighing whether to publicly disclose leaked national security information would fall to publishers, not the executive or the courts, at least in the absence of an exceedingly grave threat of harm. The lessons of the PentagonPapers case for WikiLeaks, however, are more complicated than they may first appear. The Court's per curiam opinion masks areas of substantial disagreement as well as a number of shared assumptions among the Court's members. Specifically, the Pentagon Papers case reflects an institutional framework for downstream disclosure of leaked national security information, under which publishers within the reach of U.S. law would weigh the potential harms and benefits of disclosure against the backdrop of potential criminal penalties and recognized journalistic norms. The WikiLeaks disclosures show the instability of this framework by revealing new challenges for controlling the downstream disclosure of leaked information and the corresponding likelihood of "unintermediated" disclosure by an insider; the risks of non-media intermediaries attempting to curtail such disclosures, in response to government pressure or otherwise; and the pressing need to prevent and respond to leaks at the source. AUTHOR. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Offensive Capabilities

GCHQ and UK Mass Surveillance Chapter 5 5 Beyond signals intelligence: Offensive capabilities 5.1 Introduction Documents released by German magazine Der Spiegel provide a much richer picture of the offensive activities of the NSA and its allies, including the UK’s GCHQ.i The global surveillance infrastructure and hacking tools described in the previous chapters are not only used for obtaining information to be fed into intelligence reports and tracking terrorists. The agencies are also developing cyber-warfare capabilities, with the NSA taking the lead within the US armed forces. This militarisation of the internet saw U.S. intelligence services carried out 231 offensive cyber-operations in 2011ii. The UK's National Strategic Defence and Security Review from 2010 made hostile attacks upon UK cyberspace a major priorityiii. It is fair to assume that many countries are following suit and building cyber-warfare capabilities. Der Spiegel terms the development of these aggressive hacking tools as Digital Weapons. In their view D weapons which should join the ABC (Atomic, Biological and Chemical) weapons of the 20th century because of their indiscriminate nature. Here lies a fundamental problem. The modern world with connected global communications networks means that non-state actors such as civilians and businesses are now affected by the agencies’ activities much more frequently than before. The internet is used by everyone – cyberspace is mainly a civilian space – and the opportunity for collateral damage is huge. The papers leaked to Der Spiegel appear to show that signal agencies have little regard for the security and wellbeing of anyone who gets caught in the path of their operations. -

How to Use Encryption and Privacy Tools to Evade Corporate Espionage

How to use Encryption and Privacy Tools to Evade Corporate Espionage An ICIT White Paper Institute for Critical Infrastructure Technology August 2015 NOTICE: The recommendations contained in this white paper are not intended as standards for federal agencies or the legislative community, nor as replacements for enterprise-wide security strategies, frameworks and technologies. This white paper is written primarily for individuals (i.e. lawyers, CEOs, investment bankers, etc.) who are high risk targets of corporate espionage attacks. The information contained within this briefing is to be used for legal purposes only. ICIT does not condone the application of these strategies for illegal activity. Before using any of these strategies the reader is advised to consult an encryption professional. ICIT shall not be liable for the outcomes of any of the applications used by the reader that are mentioned in this brief. This document is for information purposes only. It is imperative that the reader hires skilled professionals for their cybersecurity needs. The Institute is available to provide encryption and privacy training to protect your organization’s sensitive data. To learn more about this offering, contact information can be found on page 41 of this brief. Not long ago it was speculated that the leading world economic and political powers were engaged in a cyber arms race; that the world is witnessing a cyber resource buildup of Cold War proportions. The implied threat in that assessment is close, but it misses the mark by at least half. The threat is much greater than you can imagine. We have passed the escalation phase and have engaged directly into full confrontation in the cyberwar. -

Mass Surveillance

Mass Surveillance Mass Surveillance What are the risks for the citizens and the opportunities for the European Information Society? What are the possible mitigation strategies? Part 1 - Risks and opportunities raised by the current generation of network services and applications Study IP/G/STOA/FWC-2013-1/LOT 9/C5/SC1 January 2015 PE 527.409 STOA - Science and Technology Options Assessment The STOA project “Mass Surveillance Part 1 – Risks, Opportunities and Mitigation Strategies” was carried out by TECNALIA Research and Investigation in Spain. AUTHORS Arkaitz Gamino Garcia Concepción Cortes Velasco Eider Iturbe Zamalloa Erkuden Rios Velasco Iñaki Eguía Elejabarrieta Javier Herrera Lotero Jason Mansell (Linguistic Review) José Javier Larrañeta Ibañez Stefan Schuster (Editor) The authors acknowledge and would like to thank the following experts for their contributions to this report: Prof. Nigel Smart, University of Bristol; Matteo E. Bonfanti PhD, Research Fellow in International Law and Security, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Pisa; Prof. Fred Piper, University of London; Caspar Bowden, independent privacy researcher; Maria Pilar Torres Bruna, Head of Cybersecurity, Everis Aerospace, Defense and Security; Prof. Kenny Paterson, University of London; Agustín Martin and Luis Hernández Encinas, Tenured Scientists, Department of Information Processing and Cryptography (Cryptology and Information Security Group), CSIC; Alessandro Zanasi, Zanasi & Partners; Fernando Acero, Expert on Open Source Software; Luigi Coppolino,Università degli Studi di Napoli; Marcello Antonucci, EZNESS srl; Rachel Oldroyd, Managing Editor of The Bureau of Investigative Journalism; Peter Kruse, Founder of CSIS Security Group A/S; Ryan Gallagher, investigative Reporter of The Intercept; Capitán Alberto Redondo, Guardia Civil; Prof. Bart Preneel, KU Leuven; Raoul Chiesa, Security Brokers SCpA, CyberDefcon Ltd.; Prof. -

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) Warsaw 2020 MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Justyna Fruzińska, Izabella Kimak, Mirosław Miernik, Łukasz Muniowski, Jacek Partyka, Paweł Stachura ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWERS Ewa Antoszek, Edyta Frelik, Elżbieta Klimek-Dominiak, Zofia Kolbuszewska, Tadeusz Pióro, Elżbieta Rokosz-Piejko, Małgorzata Rutkowska, Stefan Schubert, Joanna Ziarkowska TYPESETTING AND COVER DESIGN Miłosz Mierzyński COVER IMAGE Jerzy Durczak, “Vegas Options” from the series “Las Vegas.” By permission. www.flickr/photos/jurek_durczak/ ISSN 1733-9154 eISSN 2544-8781 Publisher Polish Association for American Studies Al. Niepodległości 22 02-653 Warsaw paas.org.pl Nakład 110 egz. Wersją pierwotną Czasopisma jest wersja drukowana. Printed by Sowa – Druk na życzenie phone: +48 22 431 81 40; www.sowadruk.pl Table of Contents ARTICLES Justyna Włodarczyk Beyond Bizarre: Nature, Culture and the Spectacular Failure of B.F. Skinner’s Pigeon-Guided Missiles .......................................................................... 5 Małgorzata Olsza Feminist (and/as) Alternative Media Practices in Women’s Underground Comix in the 1970s ................................................................ 19 Arkadiusz Misztal Dream Time, Modality, and Counterfactual Imagination in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon ............................................................................... 37 Ewelina Bańka Walking with the Invisible: The Politics of Border Crossing in Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway: A True Story ............................................. -

Download the PDF File

S E C RE T //NOFORN I I 20310825 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE JOINT TASK FORCE GUANTANAMO GUANTANAMO BAY, CI,IBA APO AE 09360 JTF-GTMO-CC 25 August2006 MEMORANDUM FOR Commander,United StatesSouthern Command, 3511 NW 9lst Avenue. Miami. FL33172 SUBJECT: Recommendationfor Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD) for GuantanamoDetainee, ISN: US9SA-000230DP(S) JTF-GTMODetainee Assessment 1. (S/NF) PersonalInformation: o JDIMSAIDRC ReferenceName: Hamud Dakhil Hamud o Aliases and Current/True Name: Talut al-Jeddawi. Humud Dakhil Humud Said al-Jadani.Hamud Sultan.Nag Mohammad. Safwan the Afghan o Placeof Birth: Jeddah.Saudi Arabia (SA) o Dateof Birth: 22May 1973 o Citizenship: SaudiArabia o InternmentSerial Number (ISN): US9SA-000230DP 2. (FOUO) Health: Detaineeis in goodhealth. 3. (S//NF) JTF-GTMOAssessment: a. (S) Recommendation: JTF-GTMOrecommends this detaineefor Continued DetentionUnder DoD Control(CD). JTF-GTMOpreviously assessed detainee as Continued DetentionUnder DoD Control(CD) on 5 September2005. b. (S/NF) Executive Summary: Detaineeis assessedto be a memberof al-Qaidawith an extensivehistory of militantjihad. Detaineeis an admittedleader of armedfighters in ToraBora duringhostilities against US forcesand associated with severalsenior al-Qaida members.He receivedbasic and advanced training in Chechnyaand Afghanistan (AF) CLASSIFIEDBY: MULTIPLESOURCES REASON:E.O. 12958 SECTION 1.5(C) DECLASSIFYON: 203108 1 I S E C RE T // NOFORNI I 20310825 S E C R E T // NOFORNI I 20310825 JTF-GTMO-CC SUBJECT:Recommendation for ContinuedDetention Under DoD Control(CD) for GuantanamoDetainee, ISN: US9SA-000230DP (S) includingtraining on smallarns, explosives,mortars, and anti-aircraft weaponry. JTF- GTMO determinedthis detaineeto be: o A HIGH risk, as he is likely to posea threatto the US, its interestsand allies. -

In the Depths of the Net by Sue Halpern | the New York Review Of

Font Size: A A A In the Depths of the Net Sue Halpern OCTOBER 8, 2015 ISSUE The Dark Net: Inside The Digital Underworld by Jamie Bartlett Melville House, 308 pp, $27.95 freeross.org Ross Ulbricht, who was recently sentenced to life in prison for running the illegal dark-Net marketplace Silk Road Early this year, a robot in Switzerland purchased ten tablets of the illegal drug MDMA, better known as “ecstasy,” from an online marketplace and had them delivered through the postal service to a gallery in St. Gallen where the robot was then set up. The drug buy was part of an installation called “Random Darknet Shopper,” which was meant to show what could be obtained on the “dark” side of the Internet. In addition to ecstasy, the robot also bought a baseball cap with a secret camera, a pair of knock-off Diesel jeans, and a Hungarian passport, among other things. Passports stolen and forged, heroin, crack cocaine, semiautomatic weapons, people who can be hired to use those weapons, computer viruses, and child pornography—especially child pornography—are all easily obtained in the shaded corners of the Internet. For example, in the interest of research, Jamie Bartlett—the author of The Dark Net: Inside the Digital Underworld, a picturesque tour of this disquieting netherworld—successfully bought a small amount of marijuana from a dark-Net site; anyone hoping to emulate him will find that the biggest dilemma will be with which seller—there are scores—to do business. My own forays to the dark Net include visits to sites offering counterfeit drivers’ licenses, methamphetamine, a template for a US twenty-dollar bill, files to make a 3D-printed gun, and books describing how to receive illegal goods in the mail without getting caught. -

The Qanon Conspiracy

THE QANON CONSPIRACY: Destroying Families, Dividing Communities, Undermining Democracy THE QANON CONSPIRACY: PRESENTED BY Destroying Families, Dividing Communities, Undermining Democracy NETWORK CONTAGION RESEARCH INSTITUTE POLARIZATION AND EXTREMISM RESEARCH POWERED BY (NCRI) INNOVATION LAB (PERIL) Alex Goldenberg Brian Hughes Lead Intelligence Analyst, The Network Contagion Research Institute Caleb Cain Congressman Denver Riggleman Meili Criezis Jason Baumgartner Kesa White The Network Contagion Research Institute Cynthia Miller-Idriss Lea Marchl Alexander Reid-Ross Joel Finkelstein Director, The Network Contagion Research Institute Senior Research Fellow, Miller Center for Community Protection and Resilience, Rutgers University SPECIAL THANKS TO THE PERIL QANON ADVISORY BOARD Jaclyn Fox Sarah Hightower Douglas Rushkoff Linda Schegel THE QANON CONSPIRACY ● A CONTAGION AND IDEOLOGY REPORT FOREWORD “A lie doesn’t become truth, wrong doesn’t become right, and evil doesn’t become good just because it’s accepted by the majority.” –Booker T. Washington As a GOP Congressman, I have been uniquely positioned to experience a tumultuous two years on Capitol Hill. I voted to end the longest government shut down in history, was on the floor during impeachment, read the Mueller Report, governed during the COVID-19 pandemic, officiated a same-sex wedding (first sitting GOP congressman to do so), and eventually became the only Republican Congressman to speak out on the floor against the encroaching and insidious digital virus of conspiracy theories related to QAnon. Certainly, I can list the various theories that nest under the QAnon banner. Democrats participate in a deep state cabal as Satan worshiping pedophiles and harvesting adrenochrome from children. President-Elect Joe Biden ordered the killing of Seal Team 6.