Ecosystem Integrity and Community Participation Related to Water Availability Within and Around Calakmul Biosphere Reserve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Maya City of Calakmul, Campeche

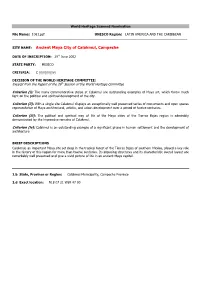

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1061.pdf UNESCO Region: LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Ancient Maya City of Calakmul, Campeche DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 29th June 2002 STATE PARTY: MEXICO CRITERIA: C (i)(ii)(iii)(iv) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 26th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (i): The many commemorative stelae at Calakmul are outstanding examples of Maya art, which throw much light on the political and spiritual development of the city. Criterion (ii): With a single site Calakmul displays an exceptionally well preserved series of monuments and open spaces representative of Maya architectural, artistic, and urban development over a period of twelve centuries. Criterion (iii): The political and spiritual way of life of the Maya cities of the Tierras Bajas region is admirably demonstrated by the impressive remains of Calakmul. Criterion (iv): Calakmul is an outstanding example of a significant phase in human settlement and the development of architecture BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Calakmul, an important Maya site set deep in the tropical forest of the Tierras Bajas of southern Mexico, played a key role in the history of this region for more than twelve centuries. Its imposing structures and its characteristic overall layout are remarkably well preserved and give a vivid picture of life in an ancient Maya capital. 1.b State, Province or Region: Calakmul Municipality, Campeche Province 1.d Exact location: N18 07 21 W89 47 00 ANTIGUA CIUDAD MAYA DE CALAKMUL CAMPECHE INSCRIPTION A LA LISTE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL . 0 LOCALISATION ET DELIMITATION . 1 1. -

Tapir Population Patterns Under the Disappearance of Free- Standing Water

THERYA, 2019, Vol. 10 (3): XXX-XXX DOI: 10.12933/therya-19-902 ISSN 2007-3364 Tapir population patterns under the disappearance of free- standing water RAFAEL REYNA-HURTADO1*, DAVID SIMA-PANTÍ2, MARIA ANDRADE3, ANGELICA PADILLA3, OSCAR RETANA-GUAISCON4, KHIAVETT SANCHEZ-PINZÓN1, WILBER MARTINEZ1, NINON MEYER5, JOSÉ FERNANDO MOREIRA-RAMÍREZ6, NATALIA CARRILLO-REYNA7, CRYSIA MARINA RIVERO-HERNÁNDEZ1,8, ISABEL SERRANO MAC- GREGOR1, SOPHIE CALME9 AND NICOLAS ARIAS DOMINGUEZ10. 1 El Colegio de la Frontera Sur Unidad Campeche. Avenida Rancho s/n, Poligono 2ª, Lerma. Campeche, México. Email: rreyna@ ecosur.mx (RR-H), [email protected] (KS-P), [email protected] (WM), [email protected] (CMR), isabel_ [email protected] (IS-M). 2 CONANP, Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, CP. 24640, Xpujil, Calakmul. Campeche, Mexico. Email: david.sima@ conanp.mx (DSP). 3 Pronatura Península de Yucatán. Calle 32#269, CP. 97205, Merida. Yucatán. Mexico. Email: [email protected] (MA), [email protected] (AP). 4 Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, CP. 24029, Campeche. Campeche, México. Email: [email protected] (ORG). 5 Fundación Yaguara, Ciudad del Saber, Panama City, Panama. Email: [email protected] (NM). 6 Wildlife Conservation Society, Guatemala Programa. Guatemala City, Guatemala. Email: [email protected] (JM-R). 7 El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Unidad San Cristobal, Avenida Ma Auxiliadora, CP. 29290. San Cristobal de las Casas. Chiapas, Mexico. Email: [email protected] (NC-R). 8 Bioconciencia, A. C. Ciudad de México, México. Email: [email protected] (CMR). 9 El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Unidad Chetumal, Avenida Centenario Km5.5, CP. 77014, Chetumal. -

Soot Sayers: an Integrated Approach to Charcoal Production in Calakmul, Mexico

SOOT SAYERS: AN INTEGRATED APPROACH TO CHARCOAL PRODUCTION IN CALAKMUL, MEXICO By SAM SCHRAMSKI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Sam Schramski 2 To Don Eliseo Ek, a Calakmul institution unto himself 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Though not my first thesis undertaking in life, this is by far the most collaborative. Without the guidance from my supervisory committee, in particular my chair, Dr. Eric Keys, my research would have progressed little. Dr. Keys suffered the meanderings of someone non-geographical in his academic training stoically. The usual plaudits must also be given to my family, who suffered the meandering of someone nonsensical in his life training as well. Special credit must be given to my beleaguered undergraduate assistant, Thomas Felsmaier, whose spirited attempt at mapmaking really allowed me to call this a thesis in geography. Finally, credit must be given to the hardworking campesinos of Calakmul who provided me with endless surprises and dispelled some of my more rigid preconceptions. It is very difficult indeed to work with a city slickin’ güero who knows so little about country life. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................................... 4 LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................................................... -

Latin American Deer Diversity and Conservation: a Review of Status and Distribution

Durham E-Theses Ecology and conservation of sympatric tropical deer populations in the Greater Calakmul Region, south-eastern Mexico Weber, Manuel How to cite: Weber, Manuel (2005) Ecology and conservation of sympatric tropical deer populations in the Greater Calakmul Region, south-eastern Mexico, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2777/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 f Ecology and conservation of sympatric tropical deer populations in the Greater Calakmul Region, south-eastern Mexico by Manuel Weber A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published ^ , without his prior written consent V and information derived from it should be acknowledged. School of Biological and Biomedical Sciences University of Durham Durham, United Kingdom April 2005 This thesis is submitted in candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 t SEP 2005 Declaration The material contained in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree at the University of Durham or any other university. -

Handbook T-II

Handbook T-II Sustentabilidad, Turismo y Educación NIÑO-GUTIÉRREZ, Naú Silverio VALENCIA-GUTIÉRREZ, Marvel del Carmen GARCÍA-RAMÍREZ, María de Jesús Coordinadores ECORFAN® ECORFAN® Coordinadores NIÑO-GUTIÉRREZ, Naú Silverio VALENCIA-GUTIÉRREZ, Marvel del Carmen GARCÍA-RAMÍREZ, María de Jesús Editor en Jefe VARGAS-DELGADO, Oscar. PhD Directora Ejecutiva RAMOS-ESCAMILLA, María. PhD Director Editorial PERALTA-CASTRO, Enrique. MsC Diseñador Web ESCAMILLA-BOUCHAN, Imelda. PhD Diagramador Web LUNA-SOTO, Vladimir. PhD Asistente Editorial SORIANO-VELASCO, Jesus. BsC Traductor DÍAZ-OCAMPO, Javier. BsC Filóloga RAMOS-ARANCIBIA, Alejandra. BsC ISBN: 978-607-8695-29-4 Sello Editorial ECORFAN: 607-8695 Número de Control HSTE: 2020-03 Clasificación HSTE (2020): 200920-0103 ©ECORFAN-México, S.C. Ninguna parte de este escrito amparado por la Ley Federal de Derechos de Autor, podrá ser reproducida, transmitida o utilizada en cualquier forma o medio, ya sea gráfico, electrónico o mecánico, incluyendo, pero sin limitarse a lo siguiente: Citas en artículos y comentarios bibliográficos de compilación de datos periodísticos radiofónicos o electrónicos. Para los efectos de los artículos 13, 162,163 fracción I, 164 fracción I, 168, 169,209 fracción III y demás relativos de la Ley Federal de Derechos de Autor. Violaciones: Ser obligado al procesamiento bajo ley de copyright mexicana. El uso de nombres descriptivos generales, de nombres registrados, de marcas registradas, en esta publicación no implican, uniformemente en ausencia de una declaración específica, que tales nombres son exentos del protector relevante en leyes y regulaciones de México y por lo tanto libre para el uso general de la comunidad científica internacional. HSTE es parte de los medios de ECORFAN (www.ecorfan.org) Handbooks Definición de Handbooks Objetivos Científicos Apoyar a la Comunidad Científica Internacional en su producción escrita de Ciencia, Tecnología en Innovación en las Áreas de investigación CONACYT y PRODEP. -

Yucatan Peninsula), Mexico, Over a Period of Two Years

ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL Hernández-Rivera MP y col. Study of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the State of Campeche (Yucatan Peninsula), Mexico, over a period of two years Mirsha Pamela Hernández-Rivera, MSc,(1) Omar Hernández-Montes, PhD,(1) Adelaido Chiñas-Pérez, MC,(2) Juan Miguel Batiza-Avelar, Prof. Antrop. Social,(2) Gustavo Sánchez-Tejeda, MSP,(3) Carlos Wong-Ramírez, PhD,(1) Amalia Monroy-Ostria, PhD.(1) Hernández-Rivera MP, Hernández-Montes O, Hernández-Rivera MP, Hernández-Montes O, Chiñas-Pérez A, Batiza-Avelar JM, Sánchez-Tejeda G, Chiñas-Pérez A, Batiza-Avelar JM, Sánchez-Tejeda G, Wong-Ramírez C, Monroy-Ostria A. Wong-Ramírez C, Monroy-Ostria A. Study of cutaneous leishmaniasis Estudio de la leishmaniasis cutánea in the State of Campeche (Yucatan Peninsula), en el estado de Campeche (Península de Yucatán), Mexico, over a period of two years. México, por un periodo de dos años. Salud Publica Mex 2015;57:58-65 Salud Publica Mex 2015;57:58-65. Abstract Resumen Objective. To study cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), in the Objetivo. Estudiar la leishmaniasis cutánea en Calakmul, Calakmul municipality of the Campeche State, during two Campeche, México, durante dos años. Material y mé- years. Materials and methods. Individuals with skin todos. Se estudiaron individuos con lesiones cutáneas, se lesions were evaluated. Aspirates taken from the lesions were tomaron aspirados y se inocularon medios de cultivo; se cultured, PCR was performed to diagnose the Leishmania realizó la técnica de PCR para identificar la especie deLeish- species. Results. The culture detected 42% of the samples. mania. Resultados. Los cultivos detectaron 42% de las PCR diagnosed CL in 76% of the samples; of those 38% were muestras. -

Desmodus Rotundus) in a Tropical Cattle-Ranching Landscape Rafael Ávila-Flores, Ana Lucía Bolaina-Badal, Adriana Gallegos-Ruiz and Wendy S

www.mastozoologiamexicana.org La Portada Logotipo de la Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología A. C. Nuestro logo “Ozomatli” El nombre de “Ozomatli” proviene del náhuatl se refiere al símbolo astrológico del mono en el calendario azteca, así como al dios de la danza y del fuego. Se relaciona con la alegría, la danza, el canto, las habilidades. Al signo decimoprimero en la cosmogonía mexica. “Ozomatli” es una representación pictórica de los mono arañas (Ateles geoffroyi). La especie de primate de más amplia distribución en México. “ Es habitante de los bosques, sobre todo de los que están por donde sale el sol en Anáhuac. Tiene el dorso pequeño, es barrigudo y su cola, que a veces se enrosca, es larga. Sus manos y sus pies parecen de hombre; también sus uñas. Los Ozomatin gritan y silban y hacen visajes a la gente. Arrojan piedras y palos. Su cara es casi como la de una persona, pero tienen mucho pelo.” THERYA Volumen 10, número 3 septiembre 2019 EDITORIAL Editorial Sergio Ticul Álvarez-Castañeda 211 ARTICLES Insights into the evolutionary and demographic history of the extant endemic rodents of the Galápagos Islands Contenido Susette Castañeda-Rico, Sarah A. Johnson, Scott A. Clement, Robert C. Dowler, Jesús E. Maldonado and Cody W. Edwards 213 Use of linear features by the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) in a tropical cattle-ranching landscape Rafael Ávila-Flores, Ana Lucía Bolaina-Badal, Adriana Gallegos-Ruiz and Wendy S. Sánchez-Gómez 229 Differences in metal content in liver of Heteromyids from deposits with and without previous mining operations Lía Méndez-Rodríguez and Sergio Ticul Álvarez-Castañeda 235 Identity and distribution of the Nearctic otter (Lontra canadensis) at the Río Conchos Basin, Chihuahua, Mexico. -

Deb Raj Aryal

El Colegio de la Frontera Sur Dinámica de carbono en diferentes etapas sucesionales de la selva mediana sub-perennifolia en Calakmul, Campeche TESIS Presentada como requisito parcial para optar al grado de Doctorado en Ciencias en Ecología y Desarrollo Sustentable por Deb Raj Aryal 2014 DEDICATORIA A mi madre Ana Kumari Aryal , por educarme de tener fe y determinación en la vida, también por su paciencia y valor de estar lejos de su hijo más de cuatro años. ! ! AGRADECIMIENTOS Mi agradecimiento en primer lugar es para Dr. Bernardus H J De Jong, quien ha sido la persona a quien debo la mayor parte de mi aprendizaje y formación durante el periodo de doctorado. Sus estímulos intelectuales, consejos y paciencia han sido los pilares para dar claridad e integridad a este trabajo. Mi agradecimiento especial los miembros de mi comité tutelar Dra. Susana Ochoa, Dr. Jorge Mendoza y Dra. Ligia Esparza, quienes han ofrecido sus conocimientos, experiencias y apoyo en todo momento de mi formación académica y la integridad de la tesis. A El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR), por brindarme la oportunidad de realizar mis estudios doctorales en un centro de investigación prestigiado y de alto rendimiento. A todas las personas de departamentos académicos, administrativos y laboratorios. A los profesores de los cursos que tuvieron paciencia para explicarme aun cuando mi comprensión en lengua española no era suficiente. A Dr. Rafael Reina, Yamile Castillo y Yadira Ramos de posgrado por su amable cooperación durante todo el periodo de estudio. Al personal de la biblioteca, especialmente a Malena y Lorena por su disposición constante en la búsqueda de información. -

Ester Boserup’S Legacy on Sustainability Human-Environment Interactions VOLUME 4

Ester Boserup’s Legacy on Sustainability Human-Environment Interactions VOLUME 4 Series Editor: Professor Emilio F. Moran, Michigan State University (Geography) Editorial Board: Barbara Entwisle, Univ. of North Carolina (Sociology) David Foster, Harvard University (Ecology) Helmut Haberl, Klagenfurt University (Socio-ecological System Science) Billie Lee Turner II, Arizona State University (Geography) Peter H. Verburg, University of Amsterdam (Environmental Sciences, Modeling) For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/8599 Marina Fischer-Kowalski • Anette Reenberg Anke Schaffartzik • Andreas Mayer Editors Ester Boserup’s Legacy on Sustainability Orientations for Contemporary Research Editors Marina Fischer-Kowalski Anke Schaffartzik Institute of Social Ecology Institute of Social Ecology Alpen Adria University Alpen Adria University Vienna Vienna Austria Austria Anette Reenberg Andreas Mayer Dept. Geosciences & Resource Mgmt Institute of Social Ecology University of Copenhagen Alpen Adria University København K Vienna Denmark Austria Chapter 1 is reprinted with permission from PNAS. B. L. Turner II and Marina Fischer-Kowalski. Ester Boserup: An interdisciplinary visionary relevant for sustainability. PNAS 2010, Volume 107, no. 51, pp. 21963–21965 Published with the support of Austrian Science Fund (FWF): [PUB 209-V22] ISBN 978-94-017-8677-5 ISBN 978-94-017-8678-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-017-8678-2 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg New York London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014931401 © The Editor(s)(if applicable) and the Author(s) 2014. The book is published with open access at SpringerLink.com Open Access This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncom- mercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. -

Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) in the State of Campeche, Mexico

Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical Journal of the Brazilian Society of Tropical Medicine Vol.:53:e20190299: 2020 doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0299-2019 Short Communication New report of Eratyrus cuspidatus Stål, 1859 (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) in the State of Campeche, Mexico Paulino Tamay-Segovia[1], Selene Blum-Domínguez[2], Ricardo Alejandre-Aguilar[3], Luis Alberto Núñez-Oreza[4], Betty Sarabia- Alcocer[5] and Vicente Jesús Chan-Puc[6] [1]. Laboratorio de Enfermedades Transmitidas por Vectores y Zoonosis. Centro de Investigaciones Biomédicas de la Universidad Autónoma de Campeche. Campeche, México. [2]. Laboratorio de Enfermedades Tropicales, Centro de Investigaciones Biomédicas de la Universidad Autónoma de Campeche. Campeche, México. [3]. Laboratorio de Entomología, Depto. de Parasitología Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional. Ciudad de México, México. [4]. Laboratorio de Microbiología y Biología Molecular, Centro de Investigaciones Biomédicas de la Universidad Autónoma de Campeche. Campeche, México. [5]. Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Autónoma de Campeche. Campeche, México. [6]. Facultad de Enfermería de la Universidad Autónoma de Campeche. Campeche, México. Abstract Introduction: Triatomine bugs are vectors of Trypanosoma cruzi, the etiological agent of Chagas disease. Methods: Triatomine bugs were collected and identified following established protocols. In addition, infection with T. cruzi was detected by microscopic and molecular analysis. Results: We captured an adult male specimen of the Eratyrus cuspidatus species that has not been reported in the state of Campeche. Conclusions: This finding provides new information on the distribution ofE. cuspidatus in Mexico. However, more studies are needed to determine their epidemiological significance. Keywords: Triatominae. Eratyrus cuspidatus. Sylvatic vectors. -

Calakmul (Mexico) in Terms of the Categories of Cultural Property Set out in Article 1 of the 1972 World Heritage Convention, This Is a Site

Category of property Calakmul (Mexico) In terms of the categories of cultural property set out in Article 1 of the 1972 World Heritage Convention, this is a site. No 1061 History and Description History Identification The settlement of the heavily forested Tierras Bajas region, now divided between Mexico and Guatemala, by the Maya Nomination The Ancient Maya City of Calakmul, dates to the end of the Middle Pre-Classic Period (900–300 Campeche BCE). It was formerly considered to have been an essentially egalitarian agricultural society, based on small settlements Location Calakmul Municipality, Campeche spread throughout the region, but recent discoveries have Province shown that large monumental ceremonial structures were being built, indicating a more advanced, complex form of State Party Mexico society, capable of creating such enormous structures. Date 24 August 2000 Recent excavations in Structure II at Calakmul have shown that between 400 and 200 BCE a monument some 12m high was built here. This challenged the previously held view that Nakbé (Guatemala) had been the main centre in the latter part of the Middle Pre-Classic Period. By the time of the transition to the Late Pre-Classic Period Calakmul had Justification by State Party become one of the two dominant cities in the region, the heartland of the Maya world, the other being Tikal. By virtue of the size of its main structures and its extent, this Excavations have shown that they flourished, in a state of is a town that is comparable with other, better known sites of almost continual warfare with one another, until around 900 the Mayan culture that are already inscribed on the World CE. -

Hunting Effects on the Ungulate Species in Calakmul Forest, Mexico

HUNTING EFFECTS ON THE UNGULATE SPECIES IN CALAKMUL FOREST, MEXICO By RAFAEL ANGEL REYNA-HURTADO A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2002 Copyright 2002 by Rafael Angel Reyna-Hurtado To Edith who shared with me the joy of living in Calakmul, among simple and lovely people. To my parents who taught me to love nature and simple things and who always worked hard to see their sons happy. To Maria Jose whose brief existence makes us stronger than before. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful to my advisor, George Tanner, for his constant support and his confidence in me. He helped me from the early stages of this study through to the painful editing. He also went to Mexico and spent several days at my study site. I really appreciate the time he devoted to this project; this study could not have been completed without his help. The members of my supervisory committee, Dr. Jose M. V. Fragoso (who traveled a long distance to attend my final examination) and Dr. Madan K. Oli, improved and enriched the document with their experience and deep knowledge. Eduardo Naranjo and Manuel Weber read the manuscript and their opinions were very appreciated. Eddie Ellis assisted me in the GIS analysis and Dr. Ken Portier gave excellent advice on the statistical analyses. Gerardo Garcia-Gil provided the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve map used for this study. Edith Rojas-Flores assisted me with the interviews in Xbonil ejido.