Converting Dry Latrines in the District of Budaun, Uttar Pradesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Answered On:02.12.2002 Discovery of Ancient Site by Asi Chandra Vijay Singh

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA TOURISM AND CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:2136 ANSWERED ON:02.12.2002 DISCOVERY OF ANCIENT SITE BY ASI CHANDRA VIJAY SINGH Will the Minister of TOURISM AND CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) names of the monuments in the Moradabad and Bareilly division under ASI; (b) whether Excavations conducted at Madarpur in Moradabad District of Uttar Pradesh have unearthed an archaeological site dating to 2nd century B.C.; (c) steps taken for preservation of the site and the amount allocated for the purpose; and (d) steps proposed to be taken to further explore to excavate the area? Answer MINISTER FOR TOURISM AND CULTURE (SHRI JAGMOHAN ) (a) A list of Centrally protected monuments in Moradabad and Bareilly division is annexed. (b) The excavation conducted in January, 2000 revealed findings datable to 2nd millennium B.C. (c) & (d) Steps have been taken to conserve the site. An amount of Rs.1,84,093/- has been incurred so far. Further steps have been initiated to explore adjacent areas to assess its archaeological potentiality. ANNEXURE ANNEXURE REFFERED TO IN REPLY OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.2136 TO BE ANSWERED ON 2.12.2002 REGARDING DISCOVERY OF ANCIENT SITE BY ASI (a) Moradabad Division (i) Moradabad District: S.No. Locality Name of the Centrally Protected Monument/Site 1. Alipur, Tehsil :Chandausi Amarpati Khera 2. Alipur, Tehsil:Chandausi Chandesvara Khera 3. Berni, Tehsil;Chandausi Khera or Mound reputed to be the ruin or palace or Raja Vena 4. Bherabharatpur, Tehsil Amorha Large mound, the site of an ancient temple 5. -

Proposed UGC- Minor Research Project

Introduction Regional disparity is a ubiquitous phenomenon in both developed and developing economies. But in the latter it is more acute and glaring. When economic development occurs unequally across a country, regional differences in the levels of living become an important political issue. State economies are often composed of sets of smaller and localized economies. If the national economy is to prosper then its constituent regional economies must be brought into some sort of harmony. Any attempt to implement regional balanced -growth strategy, it is necessary to identify nature and pattern of regional development, the availability of basic amenities and the quality of infrastructure available. In Uttar Pradesh too, area disparities in the level of poverty, unemployment, income, infrastructure, agriculture, industry and above all the level of living of people exist substantially across the regions. Numerous measures have been undertaken in the last sixty years of planning to achieve balanced regional development of the State, yet wide disparities in area development continues in this state. In the regional analysis of development one comes across regions which are well developed and the peopl e in such region enjoy reasonable standard of living while in others, resource utilization and development is low owing to historical circumstances or other wise, resulting in the underdeveloped of the region whereby people have a poor 1 standard of living. The problem of imbalance in regional development thus assumes a great significance. Regional development, therefore, is interpreted as intra-regional development design to solve the problems of regions lagging behind. The first connotation of regional is e conomic in which the differences in growth, in volume and structure of production, income, and employment are taken as the measure of economic progress. -

Section-VIII : Laboratory Services

Section‐VIII Laboratory Services 8. Laboratory Services 8.1 Haemoglobin Test ‐ State level As can be seen from the graph, hemoglobin test is being carried out at almost every FRU studied However, 10 percent medical colleges do not provide the basic Hb test. Division wise‐ As the graph shows, 96 percent of the FRUs on an average are offering this service, with as many as 13 divisions having 100 percent FRUs contacted providing basic Hb test. Hemoglobin test is not available at District Women Hospital (Mau), District Women Hospital (Budaun), CHC Partawal (Maharajganj), CHC Kasia (Kushinagar), CHC Ghatampur (Kanpur Nagar) and CHC Dewa (Barabanki). 132 8.2 CBC Test ‐ State level Complete Blood Count (CBC) test is being offered at very few FRUs. While none of the sub‐divisional hospitals are having this facility, only 25 percent of the BMCs, 42 percent of the CHCs and less than half of the DWHs contacted are offering this facility. Division wise‐ As per the graph above, only 46 percent of the 206 FRUs studied across the state are offering CBC (Complete Blood Count) test service. None of the FRUs in Jhansi division is having this service. While 29 percent of the health facilities in Moradabad division are offering this service, most others are only a shade better. Mirzapur (83%) followed by Gorakhpur (73%) are having maximum FRUs with this facility. CBC test is not available at Veerangna Jhalkaribai Mahila Hosp Lucknow (Lucknow), Sub Divisional Hospital Sikandrabad, Bullandshahar, M.K.R. HOSPITAL (Kanpur Nagar), LBS Combined Hosp (Varanasi), -

Bhs&Ie, up Exam Year-2021 **** Proposed Centre Allotment **** Dist

BHS&IE, UP EXAM YEAR-2021 **** PROPOSED CENTRE ALLOTMENT **** DIST-CD & NAME :- 27 BUDAUN DATE:- 26/01/2021 PAGE:- 1 CENT-CODE & NAME CENT-STATUS CEN-REMARKS EXAM SCH-STATUS SCHOOL CODE & NAME #SCHOOL-ALLOT SEX PART GROUP 1005 NEHRU ADARSH INTER COLLEGE ALAPUR BADAUN B HIGH BUM 1005 NEHRU ADARSH INTER COLLEGE ALAPUR BADAUN 99 F HIGH CUF 1070 G B GIRLS I C KAKRALA BADAUN 22 M HIGH CRM 1137 VEER SHAYA BHOO DEVI H S S JAGAT BADAUN 79 M HIGH CUM 1153 HAJI MUKHTAR SCIENCE INTER COLLEGE KAKRALA BADAUN 122 M HIGH ARF 1169 GOVT GIRLS H S S MANSA NAGLA BADAUN 6 M HIGH CRM 1211 SHREE HARNAM SINGH MEMO H S SCHOOL DHAKA MIAUN BADAUN 27 M HIGH CRM 1217 SHREE BRIJPAL SINGH MEMO H S SCHOOL DHAKA MIAUN BADAUN 24 M HIGH CRM 1257 SHRI NAUBAT SINGH H S S BABAI BHATPURA BADAUN 21 F HIGH CRM 1277 NEW HOPES PUBLIC HS SCHOOL KAKRALA BUDAUN 8 M 408 INTER BUM 1005 NEHRU ADARSH INTER COLLEGE ALAPUR BADAUN 27 F SCIENCE INTER BUM 1005 NEHRU ADARSH INTER COLLEGE ALAPUR BADAUN 74 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BUM 1007 N P I C KAKRALA BADAUN 9 M OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CUF 1070 G B GIRLS I C KAKRALA BADAUN 11 M SCIENCE INTER CUF 1076 PARWATI SALIK KANYA INTER COLLEGE ALAPUR BADAUN 15 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRM 1108 SHIVAJI S M I C MIAUN BADAUN 157 M ALL GROUP INTER CUM 1153 HAJI MUKHTAR SCIENCE INTER COLLEGE KAKRALA BADAUN 103 M SCIENCE 396 CENTRE TOTAL >>>>>> 804 1006 SIGLER MISSION GIRLS I C BADAUN B HIGH BUF 1006 SIGLER MISSION GIRLS I C BADAUN 143 F 143 INTER BUF 1006 SIGLER MISSION GIRLS I C BADAUN 63 F SCIENCE INTER BUF 1006 SIGLER MISSION GIRLS I C BADAUN 77 -

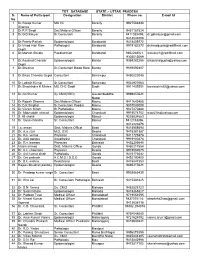

S. No Name of Participant Designation District Phone No. E-Mail Id 1 Dr

TOT DATABASE STATE :- UTTAR PRADESH S. Name of Participant Designation District Phone no. E-mail Id No 1 Dr.Anoop Kumar MO I/C Bareilly 9927568444 Sharma 2 Dr.R.P.Singh Dist.Malaria Officer Bareilly 9451157524 3 Dr.G.D.Katiyar Sr.Consultant Bareilly 9411088459, [email protected] 9412544008 4 Dr.Preety Pathak Epidemiologist Barabanki 9415409772 5 Dr.Vinod Hari Ram Pathologist Barabanki 9919182270 [email protected] Gupta 6 Dr.Manish Shukla Paediatrician Barabanki 9452268021, [email protected] 9305012069 7 Dr.Kaushal Chandar Epidemiologist Banda 9359282255 [email protected] Gupta 8 Dr.Shekhar Sr.Consultant Blood Bank Banda 9839592407 9 Dr.Bikas Chandra Gupta Consultant Balrampur 9450522045 10 Dr.Lokesh Kumar Sr.Consultant Balrampur 9532927663 11 Dr.Shachindra K.Mishra MO CHC Dadri Dadri 9911405551 [email protected] 12 Dr.Anil Kumar Dy.CMO(VBD) Gautambuddha 9999855621 Nagar 13 Dr.Rajesh Sharma Dist.Malaria Officer Meerut 9411642468 14 Dr.D.K.Singhal Sr.Consultant Paedia. Meerut 9837040009 15 Dr.Vikram Singh Sr.Pathologist Meerut 9027470880 16 Dr. Moiz uddin ahmad Epidemiologist Chandauli 9919074752 [email protected] 17 S. Ali shakir Epidemiologist Bijnour 9235834663 18 Dr. Gyan chandra Sr. Consultant Bijnour 9412153396, 9412823878 19 I.a. ansari Distt. Malaria Officer Basti 9415858694 20 Dr. A.a. rizvi M.O. (CH) Deoria 9415381387 21 Dr. R.k. verma Physician Chandauli 9411723876 22 Dr. Alok pandey Anasthetist Chandauli 9919800874 23 Dr. R.s. barnwal Physcian Bahraich 9452206645 24 Mubin ahmad Distt. Malaria Officer Gonda 9450217554 25 Dr. A.k. chaurasia Physician Deoria 9919052075 26 Dr. Anil kumar singh Pathologist Gonda 9415176042 27 Dr. -

Uttar Pradesh (UP) Dominates, and Indeed Is Often

Chapter - 1 Uttar Pradesh : An Overview ttar Pradesh (UP) dominates, and indeed is often Box 1.1: Salient Demographic and Economic Features U seen to represent, the region described as the “Hindi- of the State speaking heartland” of India. UP’s population is the highest in the country and it is the fifth largest State. 1 Population, (crore) 2001 16.62 On November 9, 2000, 13 districts of the Hill region 2 Geographical area (lakh sq.km.) 2001 2.41 as well as the district of Hardwar in the west were 3 Population density (per sq.km.) 2001 689 reconstituted into the new State of Uttaranchal. At the 4 Forest area (lakh ha.) 2001-02 16.9 moment, UP covers 240928 sq.kms. and accounts for 7.3 5 Culturable waste/usar land (lakh ha.) 2001-02 11.1 percent of total area of the country, while its share in country’s population is 16.2 percent. UP is organized into 6 Fallow land (lakh ha.) 2001-02 16.5 70 districts, 300 tehsils and 813 development blocks. There 7 Cultivated Land (lakh ha.) 2001-02 168.1 are 52028 village panchayats in the State covering 97134 8 Percentage share in total workers (2001) inhabited villages. The majority of UP’s villages are small, 1. Agriculture 66.0 with an average population of around 3194 per panchayat. 2. House hold Industries 6.0 Situated in the Indo-Gangetic plain and intersected 3. Other services 28.0 by rivers, UP has had a long history of human settlement. 9 Percentage share in State Income The fertile plains of the Ganga have led to a high (2002-03) population density and the dominance of agriculture as an economic activity. -

Fnukad 13-12-2018 Dks Lkeku; Oxz@Vuqlwfpr Tkfr@Vuqlwfpr Tutkfr Ds Vh;Ffkz;Ksa Dk P;U Buvjehfm;V Ds Vad ,Oa Jksr Ds Vk/Kkj Ij Vfhkys[Kksa Ds Vuqlkj Mi;Qdr Ik;K X;K

fnukad 13-12-2018 dks lkekU; oxZ@vuqlwfpr tkfr@vuqlwfpr tutkfr ds vH;fFkZ;ksa dk p;u bUVjehfM;V ds vad ,oa Jksr ds vk/kkj ij vfHkys[kksa ds vuqlkj mi;qDr ik;k x;k SR Father's Catego SOURC Marks PLACE OF SR NO. Name Address NO. Name ry E % POSTING DINESH VILL JODHANPURVA POST SATYAM BADAUN 1 302 CHANDRA HARPALPUR TEHSIL SAWAYAJPUR GEN ITI 79.8 TRIPATHI DEPOT TRIPATHI DIST HARDOI up pin 241402 VILLAGE AND POST KARETHI OMKAR RAMESH BADAUN 2 307 KHERA TEHSIL SHAHABAD DISTT GEN NCC 79.7 SINGH CHANDRA DEPOT RAMPUR 244922 KRISHNA VILL GAUTAM NAGAR POST KABIR BIRBAL from BADAUN 3 308 KUMAR GANJ VIA SAMPURNA NAGAR GEN ITI 79.67 MAURYA DEPOT MAURYA PILIBHIT PIN CODE 262904 MUNNA TADAK VILL AND POST TENGARAHI BADAUN 4 312 KUMAR NATH THANA BAIRIA DIST BALLIA GEN ITI 79.6 DEPOT PANDEY PANDEY 277201 UP VILL KOTIYA POST MAHSI BLOCK AMRENDRA BHAGWAN BADAUN 5 317 MAHSI PS HARDI DISTT BAHRAICH GEN ITI 79.6 KUMAR DEEN DEPOT PIN CODE 271824 VILL LADPUR POST LOHA TEH SANDEEP BADAUN 6 321 BRIJ PAL MILAK DIST RAMPUR UP PIN GEN NCC 79.5 KUMAR DEPOT CODE 244901 SURAJ RAM HARI VILL CHAMARI POST BHOPAURA BADAUN 7 322 GEN ITI 79.5 CHAUHAN CHAUHAN DISTT MAU PIN CODE275302 DEPOT RAVINDRA VILL KAMRAWAN PO BADAUN 8 327 SHIVAM NATH MANGARAWAN KADIPUR GEN ITI 79.4 DEPOT MISHRA SULTANPUR UP 228161 VILL BHANPUR POST PRAVIN RAJARAM PILIBHIT 9 328 KHUBARIYAPUR CHHIBRAMAU GEN NCC 79.4 DownloadedKUMAR BATHAM DEPOT DISTT KANNAUJ PIN 209721 RAM VILLAGE PASIGANPUR POST DURVESH PILIBHIT 10 329 KUMAR KALUAPUR TEHSIL POWYAN DISTT GEN NCC 79.4 VERMA DEPOT www.upsrtc.comVERMA SHAHJAHANPUR -

Utrition Mission (NNM)

National Nutrition Mission (NNM) States/UTs-wise Districts covered in Phase I (Year 2017-18) S.No. State / UT Number of Districts 1 Andaman and Nicobar (UT) 1 2 Andhra Pradesh 10 3 Arunachal Pradesh 1 4 Assam 5 5 Bihar 37 6 Chandigarh (UT) 1 7 Chhattisgarh 12 8 Dadra and Nagar Haveli (UT) 1 9 Daman and Diu (UT) 1 10 Delhi (NCT) 2 11 Goa 2 12 Gujarat 10 13 Haryana 2 14 Himachal Pradesh 4 15 Jammu and Kashmir 1 16 Jharkhand 18 17 Karnataka 9 18 Kerala 3 19 Lakshadweep (UT) 1 20 Madhya Pradesh 37 21 Maharashtra 22 22 Manipur 2 23 Meghalaya 5 24 Mizoram 2 25 Nagaland 2 26 Odisha 11 27 Puducherry (UT) 1 28 Punjab 4 29 Rajasthan 24 30 Sikkim 1 31 Tamil Nadu 5 32 Telangana 3 33 Tripura 1 34 Uttar Pradesh 64 35 Uttarakhand 4 36 West Bengal 6 Total Number of Districts 315 National Nutrition Mission (NNM) List of 315 Districts in 36 States/UTs covered in Phase I (Year 2017-18) S.No. State or UT Name Units District Name 1 Andaman and Nicobar (UT) 1 North and Middle Andaman 2 Andhra Pradesh 1 Anantapur 2 Chittoor 3 East Godavari 4 Kurnool 5 Prakasam 6 Srikakulam 7 Visakhapatnam 8 Vizianagaram 9 West Godavari 10 YSR District, Kadapa (Cuddapah) 3 Arunachal Pradesh 1 East Kameng 4 Assam 1 Barpeta 2 Darrang 3 Dhubri 4 Goalpara 5 Karimganj 5 Bihar 1 Araria 2 Arwal 3 Aurangabad 4 Banka 5 Begusarai 6 Bhagalpur 7 Bhojpur 8 Buxar 9 Darbhanga 10 East Champaran 11 Gaya 12 Gopalganj 13 Jamui 14 Jehanabad 15 Kaimur 16 Katihar 17 Khagaria 18 Kishanganj 19 Lakhisarai 20 Madhepura 21 Madhubani 22 Munger 23 Muzaffarpur 24 Nalanda 25 Nawada 26 Patna 27 Purnia 28 Rohtas -

PLAGUE Amérique

— 293 — Notifications reçues du 27 mai au 2 juin 1966 — Notifications received from 27 May to 2 June 1966 PESTE — PLAGUE Asie — Asia C D c D C D INDE (suite) 17-23.IV 24-30.IV 1-7.V C D Amérique -- America INDIA (continued) VIET-NAM, REP. 22-28.V C D Bihar, State Nhatrang (PA) . 1 0 ÉQUATEUR — ECUADOR Saigon (excl. PA) . Is 0 Districts Darbhanga......................... 16/7 7p Chimborazo, Province 15-2I.V Hazanbagh ..................... 1 p Op Muzzaffarpur..................... 14P 4 p Alausi, Canton Darlac, Province Saharsa .... 36p 9p Achupallas, Parr. 6-12.UI 2 0 Banmethuot.............. 12j 0 Gujarat, State Chunchi, Canton Ninh-Thuân, Province Districts Chunchi, Parr. 17-23.IV 3 l Ahmedabad . 6p Op 12p Op Phanrang, District . 9s 0 Baroda ............................. ip Op K a ir a ................................. Ip Op El Oro, Province S u r a t ............... 42p 2p 32p ip 43p Op Ârenillas, Canton Mehsana ■ 21.V Victoria, Parr. 6-12.UI 4 0 CHOLÉRA — CHOLERA Kerala, State Pinas, Canton Trivandrum, D.................... 1P ip Marcabeli, Parr. 3-9.IV 1 0 Asie — Asia Madras, State Loja, Province C D Districts Calvas, Canton BIRMANIE — BURMA 22-28.V Chingleput . Ip Op Amaluza, Parr. 24-30.IV 1 0 M adurai............................. 1P Op ip ôp Tiruchirapalli...................... 4p Op Bassein ( P ) ............... 7 0 Celica, Canton Rangoon (PA) (excl. A) 1 0 Kanyakumari ■ 21.V Pindal, Parr. 27.UI-2.IV 1 0 15-21.V Maharashtra, State Pozul, Parr. 6-12.UI 1 0 Pegu, Division Districts Macara, Canton Hanthawaddy, District 4 1 Ahmednagar..................... 2P Op Amravati Tacamoros, Parr. -

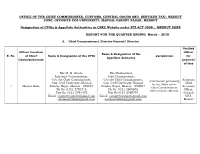

Meerut Zone, Opposite Ccs University, Mangal Pandey Nagar, Meerut

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF COMMISSIONER, CUSTOMS, CENTRAL GOODS AND SERVICES TAX:: MEERUT ZONE, OPPOSITE CCS UNIVERSITY, MANGAL PANDEY NAGAR, MEERUT Designation of CPIOs & Appellate Authorities in CBEC Website under RTI ACT 2005 :: MEERUT ZONE REPORT FOR THE QUARTER ENDING March – 2018 A. Chief Commissioner/ Director General/ Director Notified Office/ Location Officer Name & Designation of the S. No. of Chief Name & Designation of the CPIO Jurisdiction for Appellate Authority Commissionerate payment of fees Shri R. K. Gupta, Shri Roshan Lal, Assistant Commissioner, Joint Commissioner O/o the Chief Commissioner, O/o the Chief Commissioner, Assistant Information pertaining Opp. CCS University, Mangal Opp. CCS University, Mangal Chief to the Office of the 1 Meerut Zone Pandey Nagar, Meerut - 250004 Pandey Nagar, Meerut - 250004 Accounts Chief Commissioner, Ph No: 0121-2792745 Ph No: 0121-2600605 Officer, Meerut Zone, Meerut. Fax No: 0121-2761472 Fax No:0121-2769707 Central Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] GST, [email protected] [email protected] Meerut B. Commissioner/ Addl. Director General Notified S. Commission Name & Designation of the officer for Name & Designation of the CPIO Jurisdiction No. erate Appellate Authority payment of fees Areas falling Shri Kamlesh Singh Shri Roshan Lal Joint Commissioner under the Assistant Chief Assistant Commissioner Districts of Accounts O/o the Commissioner, Office of the Commissioner of Central Meerut, Officer, Office Central GST Commissionerate Goods & Services Tax, Baghpat, of the Central GST Meerut, Opp. CCS University, Commissionerate: Meerut, Opposite: Muzaffarnagar, Commissioner Meerut Mangal Pandey Nagar, Meerut. Saharanpur, 1 Chaudhary Charan Singh University, of Central Commissione Fax No: 0121-2792773 Shamli, Goods & Mangal Pandey Nagar, Meerut- rate Amroha, Services Tax, 250004 Moradabad, Commissionera Bijnore and te: Meerut Ph No: 0121-2600605 Rampur in the Fax No:0121-2769707 State of Uttar Pradesh. -

District Census Handbook, Budaun, Part X-A , Series-21, Uttar Pradesh

CENSUS 1971 PART X-A TOWN & VILLAGE DIRECTORY SERIES 21 UTTAR PRADESH DISTRICT DISTRICT BUDAUN CENSUS HANDBOOK D. M. SINHA OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SF.RVICA Director of Census Operatiom Utta.r Prad.esh , , 15 30 78°15' 30' 45' 79° , , ~ 0 30 30 ~ 0 M 0 R 0 DISTRICT BUDAUN III () -i I :u ~ )' 10 15 20 KMS. 2 I I I -l ~ " I C 01 ~ C r , I 8 15 15 )' '.q 1. ~ e / 0 ~(o'" ( II' 1- '1 ~ -9 ()/~ tr .,.~ ::> 28° i{ Q. 28° I~ :z 1~. 'Y « l: DISTRICT BOUNDAlY .. , ... ,,, .. , ." '" _._._ .... TAHSIL BOUNDAII ... '" .. , ..... , ... _._._._ VIKASKHAHD IOUNDARY .. , ... '" .. , ... " .......... "." ..... DISTIICI HEADQUARTERS '" ... '" .. , .. , @ TAHSIL HEADQUARTERS .............. • © :~ VilAS KHAND HEADQUARTERS ... .., .. , ... o I H TOWN ......... , ..... to'''' ," , e 45 VILLAGE WITH POPULATION ~GII OR MOlE .. ' IH• 33 STAT! HIGHWAY '''.'' .... " ... II' OTHER IMIORTA~ ROAD... .., .. , .. ' .. , TOWN RAILWAY LINE WITH STATION, BROAD GAUGE ... Name of thi Area in Populotion No. of No. of BY POPULATION SIZE METRE GAUGE ... I I I~II III Tohsil Km~ Villages Towns \1m AHD STREAM ' .. " ....... ,., ... ~ GUKKAUR 915.1 217,605 3e5 POLICE STAnOH ... ',. ", ", 'to ". PS BISAUll 931.9 J41,B72 180 POST ITELEGRAPH OFFICE .. • .. ' ... '" ... PT SAHASWAN 1,098.2 309,810 411 REST HOUSE, TRAVELLIRS' BUNGALOW, ETC. ; ••• iH BUOAUN 1,192.0 440,071 407 HOIIITAl, DISPENSARY, I. H. CENTRE ETC. ... + DATAGANJ 1,094.3 3 14,009 504 l~OOO DEGREE COLLEGE: H. I. SCHOOL ... ". II, 8;0 _ II,'" MANDl: IMIORTANT VILLAGE MARKIT ';6 TOTAl 5,158·0 1,045,967 2,089 0' , -

Uttar Pradesh Primary School Teachers

UTTAR PRADESH PRIMARY SCHOOL TEACHERS 1. Smt. Champa Singh Assistant Teacher, Purva Madhyamik Vidhalaya, Jungle Kodia, Distt. – Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh - 273007 2. Smt. Sonia Rani Chauhan Assistant Teacher, Upper Primary School, Abdullapur Leda, Post – Ratupura, Distt. – Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh - 244601 3. Smt. Sangeeta Sharma Assistant Teacher, Upper Primary School, Aamgaon, Distt. – Budaun, Uttar Pradesh-243635 4. Shri Mohammad Aquil Khan Head Teacher, Upper Primary School, Miaoo, Distt. – Budaun, Uttar Pradesh-242631 5. Dr. Jugal Kishore Assistant Teacher, Upper Primary School, Asrasi, Distt. – Badaun, Uttar Pradesh-243601 6. Smt. Mamta Gangwar Assistant Teacher, Upper Primary School, Barha, Distt. – Pilibhit, Uttar Pradesh-262001 7. Shri Omkar Sharma Head Master, Primary School, Pepla No. 1, Distt. – Meerut, Uttar Pradesh-250502 8. Shri Ashok Kumar Gupta Assistant Teacher, Upper Primary School, Saripur, Distt. – Bhadohi, Uttar Pradesh-221303 9. Shri Hari Shanker Shukla Head Master, Raja Baldev Das Birla Songhati Vidyalaya, Salkhan, Distt. – Sonebhadra, Uttar Pradesh-231205 10. Dr. Rambahadur Mishra Head Teacher, Upper Primary School, Narauli, Distt. - Barabanki, Uttar Pradesh-225124 11. Shri Rakesh Kumar Saini Head Teacher, Primary School, Badlugarh, Distt. - Shamli, Uttar Pradesh-247774 12. Shri Jai Prakash Rawat Assistant Teacher, Junior High School, Derhawal, Post – Derhagawa, Distt. – Chandauli, Uttar Pradesh-232106 13. Shri Lal Chand Gupta Head Master, Upper Primary School, Karamsar, Post – Panari, Distt. - Sonbhadra, Uttar Pradesh-231219 SPECIAL CATEGORY (PRIMARY) 1. Shri Bad Shah Head Teacher, Primary School, Sunderpur, Distt. – Pilibhit, Uttar Pradesh-262122 2. Shri Jai Prakash Pandey Assistant Teacher, Upper Primary School, Rewasa (Naveen), Distt. – Chandauli, Uttar Pradesh-232120 SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHERS 1. Shri Prem Kishor Sharma Principal, Amar Singh Inter College, Lakhaoti, Distt.