Technological Change and Canada/U.S. Regulatory Models for Information, Communications, and Entertainment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

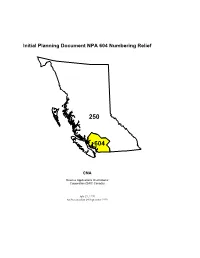

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief 250 604 CNA Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC Canada) July 27, 1999 As Presented on 24 September 1999 INITIAL PLANNING DOCUMENT NPA 604 NUMBERING RELIEF JULY 27, 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 3. CENTRAL OFFICE CODE EXHAUST .................................................................................................... 2 4. CODE RELIEF METHODS...................................................................................................................... 3 4.1. Geographic Split.............................................................................................................................. 3 4.1.1. Definition ...................................................................................................................................... 3 4.1.2. General Attributes ........................................................................................................................ 4 4.2. Distributed Overlay .......................................................................................................................... 4 4.2.1. Definition ..................................................................................................................................... -

Horizon Book of Authorities

PATENTED MEDICINE PRICES REVIEW BOARD IN THE MATTER OF THE PATENT ACT R.S.C. 1985, C. P-4, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF HORIZON PHARMA PLC (THE “RESPONDENT”) AND THE MEDICINE CYSTEAMINE BITARTRATE SOLD BY THE RESPONDENT UNDER THE TRADE NAME PROCYSBI® BOOK OF AUTHORITIES OF THE RESPONDENT (MOTION TO BIFURCATE, STRIKE EVIDENCE AND FOR THE INSPECTION AND PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS) Torys LLP 79 Wellington St. W., Suite 3000 Toronto ON M5K 1N2 Fax: 416.865.7380 Sheila R. Block Tel: 416.865.7319 [email protected] Andrew M. Shaughnessy Tel: 416.865.8171 [email protected] Rachael Saab Tel: 416.865.7676 [email protected] Stacey Reisman Tel: 416.865.7537 [email protected] Counsel to Respondent, Horizon Pharma PLC INDEX 1. Board Decision – Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. and the Medicine “Soliris” (September 20, 2017) 2. Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Canada (Attorney General), 2019 FC 734 3. Celgene Corp. v. Canada (Attorney General), 2011 SCC 1 4. Board Decision – Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. and the Medicine “Soliris” (March 29, 2016) 5. Mayne Pharma (Canada) Inc. v. Aventis Pharma Inc., 2005 FCA 50 6. P.S. Partsource Inc. v. Canadian Tire Corp., 2001 FCA 8 7. Harrop (Litigation Guardian of) v. Harrop, 2010 ONCA 390 8. Merck & Co v. Canada (Minister of Health), 2003 FC 1511 9. Vancouver Airport Authority v. Commissioner of Competition, 2018 FCA 24 10. Merck & Co, Inc. v. Canada (Minister of Health), 2003 FC 1242 11. H-D Michigan Inc. v. Berrada, 2007 FC 995 12. Roger T. Hughes, Arthur Renaud & Trent Horne, Canadian Federal Courts Practice 2019 (Toronto: LexisNexis Canada Inc., 2019) 13. -

Global Telecommunications Primer

MORGAN STANLEY DEAN WITTER Equity Research June 1999 Global Telecommunications Global Telecommunications Primer A Guide to the Information Superhighway The Global Telecommunications Team MORGAN STANLEY DEAN WITTER Global Telecommunications Team North America Wireline U.K/Europe Cellular Simon Flannery [email protected] (212) 761-6432 Fanos Hira [email protected] (44171) 425-6675 Margaret Berghausen [email protected] (212) 761-6392 Jerry Dellis [email protected] (44171) 425-5371 April Henry [email protected] (212) 761-4669 U.K./Europe Alternative Carriers Peter Kennedy [email protected] (212) 761-8033 Edings Thibault [email protected] (212) 761-8553 Saeed Baradar [email protected] (44171) 425-6594 Myles Davis [email protected] (212) 761-6916 Vathana Ly Vath [email protected] (44171) 425-6014 Richard Lee [email protected] (212) 761-3685 Europe Emerging Markets North America Data & Internet Services Damon Guirdham [email protected] (44171) 425-6665 Jeffrey Camp [email protected] (212) 761-3112 Anton Inshutin [email protected] (7 503) 785-2232 Stephen Flynn [email protected] (212) 761-8294 Latin America North America Wireless Luiz Carvalho [email protected] (212) 761-4876 Colette Fleming [email protected] (212) 761-8223 Vera R. Rossi [email protected] (212) 761-4484 Mark Kinarney [email protected] (212) 761-6342 Steve Amaro [email protected] (212) 761-3403 North America Independents and Rural Telephony Asia/Pacific Steven Franck [email protected] (212) 761-7124 Mark Shuper [email protected] (65) 439-8954 Bhaskar Dole [email protected] (9122) 209-6600 Canada David Langford [email protected] (612) 9770-1583 Greg MacDonald -

City of Toronto Customized Global Template

STAFF REPORT June 18, 2001 To: Economic Development Committee From: Joe Halstead, Commissioner Economic Development, Culture and Tourism Subject: South Etobicoke Employer Cluster Capacity Study Etobicoke-Lakeshore - Ward 6 Purpose: The purpose of this report is to provide an overview on the findings and recommendations contained in the South Etobicoke Employer Cluster Capacity Study. Financial Implications and Impact Statement: There are no financial implications resulting from the adoption of this report. Recommendations: It is recommended that: (1) the findings and recommendations of the South Etobicoke Employer Cluster Capacity Study be endorsed by the Economic Development and Parks Committee and Council; (2) this report be forwarded to the Planning and Transportation Committee and Etobicoke Community Council for their information and consideration when reviewing land use options for the New Toronto Secondary Plan; (3) the Commissioner of Economic Development, Culture and Tourism be requested to monitor and report on implementation of the South Etobicoke Employer Cluster Capacity Action Plan; and (4) the appropriate City officials be authorized and directed to take necessary action to give effect thereto. - 2 - Background: South Etobicoke is located in the southwest quadrant of the City and includes the area south of the Queen Elizabeth Highway to Lake Ontario and west of the Humber River to the Etobicoke Creek, as shown on Attachment No. 1. In 1999, South Etobicoke was identified as an “Employment Revitalization Program Area” and private and public resources (including funds from Human Resources Development Canada) were successfully leveraged to revitalize the area. This initiative has facilitated a collaborative community based process designed to encourage reinvestment in the community. -

Communications Network Builders Corporate Profile

Communications Network Builders Corporate Profile Corporate Profile OUR HISTORY Founded in 1967, TELECON quickly established itself with itsits expertise in burying communication cablecabless and a technical service provider to industry leaders such as BBellellellell Canada. FFFromFrom the startstart,,,, TELECON stood out for ititss commitment to quality workmanshipworkmanship and on time deldeliveries.iveries. In the early 1970’s, TELECON widened its array of servicesservices by adding underground infrastructure construction and utility pole installation servicesservices.. Consequently it obtainobtainedededed thethethe contract to renew the entire aerial network of the Abitibi region installtallinginginging over 600 km of specialized cable. This later led to itsitsits diversification into television cacableble distribution and mandates to deploy communicationcommunication networks across the Province of Quebec. The 90’s wewerere markmarkeded by major technological and core business changeschanges in the teletelecommunicationcommunication industries. ThTheseese opportunities led us into specialized sectors suchsuch as wireless technology, optical networknetworkssss deployment, and switched networks supporting voice data and vivivideovi deo servicesservices.. TELECON is a unique partner, one that mastersmasters alalll the necessary elements for the construction of leading edge telecommunication and electrical netwonetworkrkrkssss.... TELECON services are available from coast to coast, using only qualified and certicertifiedfied personnel -

The State of Competition in Canada's Telecommunications Industry

RESEARCH PAPERS MAY 2015 THE STATE OF COMPETITION IN CANADA’S TELECOMMUNICATIONS INDUSTRY – 2015 By Martin Masse and Paul Beaudry The Montreal Economic Institute is an independent, non-partisan, not-for-profi t research and educational organization. Through its publications, media appearances and conferences, the MEI stimu- lates debate on public policies in Quebec and across Canada by pro- posing wealth-creating reforms based on market mechanisms. It does 910 Peel Street, Suite 600 not accept any government funding. Montreal (Quebec) H3C 2H8 Canada The opinions expressed in this study do not necessarily represent those of the Montreal Economic Institute or of the members of its Phone: 514-273-0969 board of directors. The publication of this study in no way implies Fax: 514-273-2581 that the Montreal Economic Institute or the members of its board of Website: www.iedm.org directors are in favour of or oppose the passage of any bill. Reproduction is authorized for non-commercial educational purposes provided the source is mentioned. ©2015 Montreal Economic Institute ISBN 978-2-922687-59-0 Legal deposit: 2nd quarter 2015 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Library and Archives Canada Printed in Canada Martin Masse Paul Beaudry The State of Competition in Canada’s Telecommunications Industry – 2015 Montreal Economic Institute • May 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS .......................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................7 -

PRIMUS TELECOMMUNICATIONS GROUP, INCORPORATED (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2007 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission File No. 0-29092 PRIMUS TELECOMMUNICATIONS GROUP, INCORPORATED (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 54-1708481 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 7901 Jones Branch Drive, Suite 900, McLean, VA 22102 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (703) 902-2800 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered None N/A Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Common Stock, par value $.01 per share Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Letter to Kirsten Walli

FILED ELECTRONICALLY AND VIA COURIER Helen T Newland Helen.Newland@FMC‐law.com July 26, 2011 DIRECT 416‐863‐4471 Ms. Kirsten Walli Board Secretary Ontario Energy Board 2300 Yonge Street PO Box 2319, 27th Floor Toronto, ON M4P 1E4 Dear Ms. Walli: RE: Application by Canadian Distributed Antenna Systems Coalition ("CANDAS"); Board File No.: EB‐2011‐0120 We represent CANDAS in connection with its application to the Board regarding access to the power poles of licensed electricity distributors for the purpose of attaching wireless telecommunications equipment (“Application”). In accordance with Procedural Order No. 1, CANDAS is filing the written evidence of: Mr. Bob Boron, Public Mobile Inc.; Mr. Tormod Larsen, ExteNet Systems, Inc.; Ms. Johanne Lemay, Lemay‐Yates Associates Inc.; Mr. Brian O’Shaughnessy, Public Mobile Inc.; and Mr. George Vineyard, ExteNet Systems, Inc. CANDAS will file two paper copies of the above‐noted evidence tomorrow. Yours very truly, (signed) H.T. Newland HTN/ko cc: Mr. George Vinyard ExteNet Systems, Inc. Mr. Mark Rodger Borden Ladner Gervais All Intervenors 10106755_1|TorDocs Board File No. EB‐2011‐0120 ONTARIO ENERGY BOARD IN THE MATTER OF the Ontario Energy Board Act, 1998, S.O. 1998, c. 15 (Schedule B); AND IN THE MATTER OF an Application by the Canadian Distributed Antenna Systems Coalition for certain orders under the Ontario Energy Board Act, 1998. WRITTEN EVIDENCE OF GEORGE A. VINYARD 26 July 2011 10108033_2|TorDocs10108033_2.DOC Board File No. EB‐2011‐0120 Page 2 A. INTRODUCTION Q.1 Who is ExteNet Systems and what is its business? A. ExteNet Systems (Canada), Inc. -

Voice Over Internet Protocol (Voip) Competitive Landscape

Attachment 1 Page 1 of 69 Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) Competitive Landscape 28 July 2005 "For many, the phone jack in the wall that connects to the phone company's network is just a useless hole." Wall Street Journal; August 25, 2004 Attachment 1 Page 2 of 69 Table of Contents Page 1.0 GENERAL .........................................................................................................................3 2.0 RESIDENTIAL MARKET...................................................................................................8 2.1 Introduction............................................................................................................8 2.2 Competitive Overview ...........................................................................................9 2.2.1 VoIP Service Providers..............................................................................9 2.2.1.1 Telephony Offered by Cablecos ...............................................16 2.2.1.2 VoIP Forecasts .........................................................................24 2.2.2 Wireless Voice.........................................................................................26 2.2.3 Fixed Line Voice ......................................................................................29 2.2.4 Fixed and Wireless Text ..........................................................................31 2.3 Competitive Intensity ...........................................................................................32 3.0 Business market..............................................................................................................40 -

We Listen. We Help. Annual Report 2011-12

We listen. We help. Annual Report 2011-12 www.ccts-cprst.ca [email protected] 1-888-221-1687 CCTS Annual Report 2011-12 Contents Message from the Chair of the 2 Participating Service Providers 20 Board of Directors, Mary Gusella Signing Up Service Providers Message from the Commissioner, Howard Maker 3 Working with Service Providers to Improve Who We Are & What We Do: Our Mandate 4 Process and Resolve Complaints Our Complaints Process: How it Works 5 Penalizing Customers for Complaints to CCTS The Year in Review – Highlights of 2011-12 6 List of Participating Service Providers Dealing with Customer Complaints Customer Survey 23 Deposit and Disconnection Code What Customers Said About CCTS A National Wireless Code What Customers Said About Service Provider Public Awareness Update “Public Awareness” Activities 2011-12 Complaints 8 Who We Are 27 2011-12 Operational Statistics Report Our Board of Directors Summary of Leading Complaint Issues Our Team Summary of Issues Raised in Complaints Statistics 30 Topics + Trends 12 Definitions Billing Detailed Analysis of Issues Raised in Complaints Case Study #1 – Phantom Service Analysis of Closed Complaints Case Study #2 – But it’s all in my bill… Compensation Analysis Case Study #3 – Why didn’t you just tell me?! Out-of-Mandate Complaints Contract Disputes Contact Centre Activities Case Study #4 – Contract? What contract? Complaints by Service Provider Case Study #5 – Where did it say that? Complaints by Province Case Study #6 – I didn’t ask you to Contact Us 47 make that change Service Delivery -

The Consumer Case for Telecom Reform and Results-Based Regulation

Waiting for the Dream: The Consumer Case for Telecom Reform and Results-Based Regulation By: Michael Janigan Public Interest Advocacy Centre 1204 - ONE Nicholas St. Ottawa, ON K1N 7B7 December 2010 1 Copyright 2010 PIAC Contents may not be commercially reproduced. Any other reproduction with acknowledgment is encouraged. The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) Suite 1204 ONE Nicholas Street Ottawa, ON K1N 7B7 Canadian Cataloguing and Publication Data Waiting for the Dream: The Consumer Case for Telecom Reform and Results-Based Regulation ISBN 1-895060-96-6 2 Acknowledgement The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) received funding from Industry Canada’s Contributions Program for Non-profit Consumer and Voluntary Organizations. The views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of Industry Canada or of the Government of Canada. The assistance with research and editing of this report provided by Michael DeSantis, Laman Meshadiyeva, Eden Maher, Amy Zhao and Janet Lo is also gratefully acknowledged. 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Summary of Recommendations .................................................................................................................. 10 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ -

Annual Information Form

2005 ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM BCE INC. FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2005 MARCH 1, 2006 WHAT’S INSIDE p. 1 ABOUT THIS ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM................ 2 Documents incorporated by reference.................................. 2 Trademarks ........................................................................ 2 About forward-looking statements...................................... 3 ABOUT BCE ......................................................................... 3 Our strategic priorities....................................................... 5 Our corporate structure ...................................................... 7 Our directors and officers ................................................... 8 Our employees ................................................................... 11 Our capital structure .......................................................... 11 Our dividend policy ........................................................... 17 ABOUT OUR BUSINESSES .................................................. 17 Bell Canada........................................................................ 17 Other BCE Segment........................................................... 22 OUR POLICY ON CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY ........... 24 BUSINESS HIGHLIGHTS..................................................... 25 THE REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT WE OPERATE IN.. 28 Legislation that governs our business .................................. 28 Key regulatory issues.......................................................... 30 Consultations