Horizon Book of Authorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confusing Patent Eligibility

CONFUSING PATENT ELIGIBILITY DAVID 0. TAYLOR* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 158 I. CODIFYING PATENT ELIGIBILITY ....................... 164 A. The FirstPatent Statute ........................... 164 B. The Patent Statute Between 1793 and 1952................... 166 C. The Modern Patent Statute ................ ..... 170 D. Lessons About Eligibility Law ................... 174 II. UNRAVELING PATENT ELIGIBILITY. ........ ............. 178 A. Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs............ 178 B. Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int'l .......... .......... 184 III. UNDERLYING CONFUSION ........................... 186 A. The Requirements of Patentability.................................. 186 B. Claim Breadth............................ 188 1. The Supreme Court's Underlying Concerns............ 189 2. Existing Statutory Requirements Address the Concerns with Claim Breadth .............. 191 3. The Supreme Court Wrongly Rejected Use of Existing Statutory Requirements to Address Claim Breadth ..................................... 197 4. Even if § 101 Was Needed to Exclude Patenting of Natural Laws and Phenomena, A Simple Statutory Interpretation Would Do So .................... 212 C. Claim Abstractness ........................... 221 1. Problems with the Supreme Court's Test................221 2. Existing Statutory Requirements Address Abstractness, Yet the Supreme Court Has Not Even Addressed Them.............................. 223 IV. LACK OF ADMINISTRABILITY ....................... ....... 227 A. Whether a -

Patent Law: a Handbook for Congress

Patent Law: A Handbook for Congress September 16, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46525 SUMMARY R46525 Patent Law: A Handbook for Congress September 16, 2020 A patent gives its owner the exclusive right to make, use, import, sell, or offer for sale the invention covered by the patent. The patent system has long been viewed as important to Kevin T. Richards encouraging American innovation by providing an incentive for inventors to create. Without a Legislative Attorney patent system, the reasoning goes, there would be little incentive for invention because anyone could freely copy the inventor’s innovation. Congressional action in recent years has underscored the importance of the patent system, including a major revision to the patent laws in 2011 in the form of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act. Congress has also demonstrated an interest in patents and pharmaceutical pricing; the types of inventions that may be patented (also referred to as “patentable subject matter”); and the potential impact of patents on a vaccine for COVID-19. As patent law continues to be an area of congressional interest, this report provides background and descriptions of several key patent law doctrines. The report first describes the various parts of a patent, including the specification (which describes the invention) and the claims (which set out the legal boundaries of the patent owner’s exclusive rights). Next, the report provides detail on the basic doctrines governing patentability, enforcement, and patent validity. For patentability, the report details the various requirements that must be met before a patent is allowed to issue. -

Hill Times, Health Policy Review, 17NOV2014

TWENTY-FIFTH YEAR, NO. 1260 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2014 $4.00 HEARD ON THE HILL BUZZ NEWS HARASSMENT Artist paints Queen, other prominent MPs like ‘kings, queens in their people, wants a national portrait gallery little domains,’ contribute to ‘culture of silence’: Clancy BY LAURA RYCKEWAERT “The combination of power and testosterone often leads, unfortu- n arm’s-length process needs nately, to poor judgment, especially Ato be established to deal in a system where there has been with allegations of misconduct no real process to date,” said Nancy or harassment—sexual and Peckford, executive director of otherwise—on Parliament Hill, Equal Voice Canada, a multi-par- say experts, as the culture on tisan organization focused on the Hill is more conducive to getting more women elected. inappropriate behaviour than the average workplace. Continued on page 14 NEWS HARASSMENT Campbell, Proctor call on two unnamed NDP harassment victims to speak up publicly BY ABBAS RANA Liberal Senator and a former A NDP MP say the two un- identifi ed NDP MPs who have You don’t say: Queen Elizabeth, oil on canvas, by artist Lorena Ziraldo. Ms. Ziraldo said she got fed up that Ottawa doesn’t have accused two now-suspended a national portrait gallery, so started her own, kind of, or at least until Nov. 22. Read HOH p. 2. Photograph courtesy of Lorena Ziraldo Liberal MPs of “serious person- al misconduct” should identify themselves publicly and share their experiences with Canadians, NEWS LEGISLATION arguing that it is not only a ques- tion of fairness, but would also be returns on Monday, as the race helpful to address the issue in a Feds to push ahead on begins to move bills through the transparent fashion. -

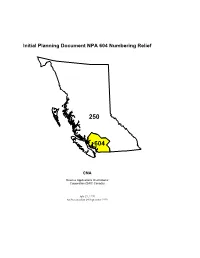

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief 250 604 CNA Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC Canada) July 27, 1999 As Presented on 24 September 1999 INITIAL PLANNING DOCUMENT NPA 604 NUMBERING RELIEF JULY 27, 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 3. CENTRAL OFFICE CODE EXHAUST .................................................................................................... 2 4. CODE RELIEF METHODS...................................................................................................................... 3 4.1. Geographic Split.............................................................................................................................. 3 4.1.1. Definition ...................................................................................................................................... 3 4.1.2. General Attributes ........................................................................................................................ 4 4.2. Distributed Overlay .......................................................................................................................... 4 4.2.1. Definition ..................................................................................................................................... -

Compulsory Patent Licensing: Is It a Viable Solution in the United States Carol M

Michigan Telecommunications and Technology Law Review Volume 13 | Issue 2 2007 Compulsory Patent Licensing: Is It a Viable Solution in the United States Carol M. Nielsen Michael R. Samardzija University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.umich.edu/mttlr Part of the Administrative Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Carol M. Nielsen & Michael R. Samardzija, Compulsory Patent Licensing: Is It a Viable Solution in the United States, 13 Mich. Telecomm. & Tech. L. Rev. 509 (2007). Available at: http://repository.law.umich.edu/mttlr/vol13/iss2/9 This Symposium Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Telecommunications and Technology Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPULSORY PATENT LICENSING: IS IT A VIABLE SOLUTION IN THE UNITED STATES? Carol M. Nielsen* Michael R. Samardzija** Cite as: Carol M. Nielsen and Michael R. Samardzija, Compulsory Patent Licensing: Is It a Viable Solution in the United States?, 13 MICH. TELECOMM. TECH. L. REV. 509 (2007), available at http://www.mttlr.org/volthirteen/nielsen&samardzija.pdf As technology continues to advance at a rapid pace, so do the number of patents that cover every aspect of making, using, and selling these innovations. In 1996, to compound the rapid change of technology, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that business methods are also patentable. -

Global Telecommunications Primer

MORGAN STANLEY DEAN WITTER Equity Research June 1999 Global Telecommunications Global Telecommunications Primer A Guide to the Information Superhighway The Global Telecommunications Team MORGAN STANLEY DEAN WITTER Global Telecommunications Team North America Wireline U.K/Europe Cellular Simon Flannery [email protected] (212) 761-6432 Fanos Hira [email protected] (44171) 425-6675 Margaret Berghausen [email protected] (212) 761-6392 Jerry Dellis [email protected] (44171) 425-5371 April Henry [email protected] (212) 761-4669 U.K./Europe Alternative Carriers Peter Kennedy [email protected] (212) 761-8033 Edings Thibault [email protected] (212) 761-8553 Saeed Baradar [email protected] (44171) 425-6594 Myles Davis [email protected] (212) 761-6916 Vathana Ly Vath [email protected] (44171) 425-6014 Richard Lee [email protected] (212) 761-3685 Europe Emerging Markets North America Data & Internet Services Damon Guirdham [email protected] (44171) 425-6665 Jeffrey Camp [email protected] (212) 761-3112 Anton Inshutin [email protected] (7 503) 785-2232 Stephen Flynn [email protected] (212) 761-8294 Latin America North America Wireless Luiz Carvalho [email protected] (212) 761-4876 Colette Fleming [email protected] (212) 761-8223 Vera R. Rossi [email protected] (212) 761-4484 Mark Kinarney [email protected] (212) 761-6342 Steve Amaro [email protected] (212) 761-3403 North America Independents and Rural Telephony Asia/Pacific Steven Franck [email protected] (212) 761-7124 Mark Shuper [email protected] (65) 439-8954 Bhaskar Dole [email protected] (9122) 209-6600 Canada David Langford [email protected] (612) 9770-1583 Greg MacDonald -

Chapter 2 Novelty and Inventive Step (Patent Act Article 29(1) and (2))

Note: When any ambiguity of interpretation is found in this provisional translation, the Japanese text shall prevail. Part III Chapter 2 Section 1 Novelty Chapter 2 Novelty and Inventive Step (Patent Act Article 29(1) and (2)) Section 1 Novelty 1. Overview Patent Act Article 29(1) provides as the unpatentable cases (i) inventions that were publicly known, (ii) inventions that were publicly worked (iii) inventions that were described in a distributed publication or made available to the public through electric telecommunication lines in Japan or a foreign country prior to the filing of the patent application. The same paragraph provides that a patent shall not be granted for these publicly known (Note) inventions (inventions lacking novelty, hereinafter referred to as "prior art” in this chapter.). The patent system is provided to grant an exclusive right to the patentee in exchange for disclosure of the invention. Therefore, the invention which deserves the patent should be novel. This paragraph is provided to achieve such a purpose. This Section describes the determination of novelty for an invention of the patent applications to be examined (hereinafter referred to as "the present application" in this Section.) (Notes) The term "publicly known" generally falls under Article 29(1)(i), or under the 29(1)(i) to (iii), hereinafter the latter is applied. 2. Determination of Novelty Inventions subject to determination of novelty are claimed inventions. The examiner determines whether the claimed invention has novelty by comparing the claimed inventions and the prior art cited for determining novelty and an inventive step (the cited prior art) to identify the differences between them. -

City of Toronto Customized Global Template

STAFF REPORT June 18, 2001 To: Economic Development Committee From: Joe Halstead, Commissioner Economic Development, Culture and Tourism Subject: South Etobicoke Employer Cluster Capacity Study Etobicoke-Lakeshore - Ward 6 Purpose: The purpose of this report is to provide an overview on the findings and recommendations contained in the South Etobicoke Employer Cluster Capacity Study. Financial Implications and Impact Statement: There are no financial implications resulting from the adoption of this report. Recommendations: It is recommended that: (1) the findings and recommendations of the South Etobicoke Employer Cluster Capacity Study be endorsed by the Economic Development and Parks Committee and Council; (2) this report be forwarded to the Planning and Transportation Committee and Etobicoke Community Council for their information and consideration when reviewing land use options for the New Toronto Secondary Plan; (3) the Commissioner of Economic Development, Culture and Tourism be requested to monitor and report on implementation of the South Etobicoke Employer Cluster Capacity Action Plan; and (4) the appropriate City officials be authorized and directed to take necessary action to give effect thereto. - 2 - Background: South Etobicoke is located in the southwest quadrant of the City and includes the area south of the Queen Elizabeth Highway to Lake Ontario and west of the Humber River to the Etobicoke Creek, as shown on Attachment No. 1. In 1999, South Etobicoke was identified as an “Employment Revitalization Program Area” and private and public resources (including funds from Human Resources Development Canada) were successfully leveraged to revitalize the area. This initiative has facilitated a collaborative community based process designed to encourage reinvestment in the community. -

Communications Network Builders Corporate Profile

Communications Network Builders Corporate Profile Corporate Profile OUR HISTORY Founded in 1967, TELECON quickly established itself with itsits expertise in burying communication cablecabless and a technical service provider to industry leaders such as BBellellellell Canada. FFFromFrom the startstart,,,, TELECON stood out for ititss commitment to quality workmanshipworkmanship and on time deldeliveries.iveries. In the early 1970’s, TELECON widened its array of servicesservices by adding underground infrastructure construction and utility pole installation servicesservices.. Consequently it obtainobtainedededed thethethe contract to renew the entire aerial network of the Abitibi region installtallinginginging over 600 km of specialized cable. This later led to itsitsits diversification into television cacableble distribution and mandates to deploy communicationcommunication networks across the Province of Quebec. The 90’s wewerere markmarkeded by major technological and core business changeschanges in the teletelecommunicationcommunication industries. ThTheseese opportunities led us into specialized sectors suchsuch as wireless technology, optical networknetworkssss deployment, and switched networks supporting voice data and vivivideovi deo servicesservices.. TELECON is a unique partner, one that mastersmasters alalll the necessary elements for the construction of leading edge telecommunication and electrical netwonetworkrkrkssss.... TELECON services are available from coast to coast, using only qualified and certicertifiedfied personnel -

Compulsory Licensing of Patented Inventions

Compulsory Licensing of Patented Inventions -name redacted- Visiting Scholar January 14, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R43266 Compulsory Licensing of Patented Inventions Summary The term “compulsory license” refers to the grant of permission for an enterprise seeking to use another’s intellectual property without the consent of its proprietor. The grant of a compulsory patent license typically requires the sanction of a governmental entity and provides for compensation to the patent owner. Compulsory licenses in the patent system most often relate to pharmaceuticals and other inventions pertaining to public health, but they potentially apply to any patented invention. U.S. law allows for the issuance of compulsory licenses in a number of circumstances, and also allows for circumstances that are arguably akin to a compulsory license. The Atomic Energy Act, Clean Air Act, and Plant Variety Protection Act provide for compulsory licensing, although these provisions have been used infrequently at best. The Bayh-Dole Act offers the federal government “march-in rights,” although these have not been invoked in the three decades since that legislation has been enacted. 28 U.S.C. Section 1498 provides the U.S. government with broad ability to use inventions patented by others. Compulsory licenses have also been awarded as a remedy for antitrust violations. Finally, a court may decline to award an injunction in favor of a prevailing patent owner during infringement litigation, an outcome that some observers believe is akin to the grant of a compulsory license. A number of international agreements to which the United States and its trading partners are signatories, including the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, World Trade Organization agreements, and certain free trade agreements, address compulsory licensing. -

Biopatents – a Threat to the Use and Conservation of Agrobiodiversity?

Advisory Board on Biodiversity and Genetic Resources at the Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection (BMELV) Biopatents – A Threat to the Use and Conservation of Agrobiodiversity? Position Paper of the Advisory Board on Biodiversity and Genetic Resources at the Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection (Translation of German original paper) May 2010 Lead author Dr. Peter H. Feindt, Cardiff University Members of the Advisory Board on Biodiversity and Genetic Resources at the BMELV (05/2010) Prof. Dr. Bärbel Gerowitt, University of Rostock (Chair) Dr. Peter H. Feindt, Cardiff University, Great Britain (Vice Chair) Dr. Frank Begemann, Federal Office for Agriculture and Food, Bonn Prof. Dr. Leo Dempfle, Technical University Muinch (TUM) Dr. Jan Engels, Bioversity International, Italy Dr. Lothar Frese, Julius Kuehn-Institute, Quedlinburg Prof. Dr. Hans-Rolf Gregorius, University of Goettingen Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Alois Heißenhuber, Technical University Muinch (TUM) Prof. Dr. Hans-Jörg Jacobsen, University of Hannover Dr. Alwin Janßen, Northwest German Forest Research Institute, Hann. Münden Dr. Ingrid Kissling-Näf, Federal Office for Professional Education and Technology, Switzerland Prof. Dr. Konrad Ott, University of Greifswald Prof. Dr. Lucia Reisch, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark Prof. em. Dr. Werner Steffens, Deutscher Fischerei-Verband e. V., (German Fisheries Association), Bonn Dr. Steffen Weigend, Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute, Federal Research Institute for Animal Health, Mariensee Citation of this paper Peter H. Feindt, Advisory Board on Biodiversity and Genetic Resources at the BMELV, 2010: Biopatents – A Threat to the Use and Conservation of Agrobiodiversity? Position Paper of the Advisory Board on Biodiversity and Genetic Resources at the Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection (BMELV), 36 pp. -

Committee on Development and Intellectual Property

E CDIP/13/10 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH DATE: MARCH 27, 2014 Committee on Development and Intellectual Property Thirteenth Session Geneva, May 19 to 23, 2014 PATENT-RELATED FLEXIBILITIES IN THE MULTILATERAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND THEIR LEGISLATIVE IMPLEMENTATION AT THE NATIONAL AND REGIONAL LEVELS - PART III prepared by the Secretariat 1. In the context of the discussions on Development Agenda Recommendation 14, Member States, at the eleventh session of the Committee on Development and Intellectual Property (CDIP) held from May 13 to 17, 2013, in Geneva, requested the International Bureau of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) to prepare a document that covers two new patent-related flexibilities. 2. The present document addresses the requested two additional patent-related flexibilities. 3. The CDIP is invited to take note of the contents of this document and its Annexes. CDIP/13/10 page 2 Table of Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………………...…….….. 3 II. THE SCOPE OF THE EXCLUSION FROM PATENTABILITY OF PLANTS..…….…….…4 A. Introduction……..……………………………………………………………………….….4 B. The international legal framework………………………………………………………. 6 C. National and Regional implementation………………………………………………… 7 a) Excluding plants from patent protection……………………………………........ 8 b) Excluding plant varieties from patent protection………………………………... 8 c) Excluding both plant and plant varieties from patent protection……...……….. 9 d) Allowing the patentability of plants and/or plant varieties……………………… 9 e) Excluding essentially biological processes for the production of plants…….. 10 III. FLEXIBILITIES IN RESPECT OF THE PATENTABILITY, OR EXCLUSION FROM PATENTABILITY, OF SOFTWARE-RELATED INVENTIONS………………………….…….…. 12 A. Introduction………………………………………………………………………….….…12 B. The International legal framework………………………………………………………13 C. National implementations……………………………………………………………….. 14 a) Explicit exclusion …………………………………………………………………. 14 b) Explicit inclusion…………………………………………………………………... 16 c) No specific provision……………………………………………………………… 16 D.