Harvard School of Public Health | Panel 4: Public Health Education Unbound - Transforming the Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae ALAN MICHAEL GARBER Mailing Address

Dec 2012 Curriculum Vitae ALAN MICHAEL GARBER Mailing Address: Office of the Provost Massachusetts Hall Harvard Yard Cambridge, MA 02138 Telephone: 617/496-5100 Facsimile number: 617/495-8550 Electronic mail: [email protected] Year of Birth: 1955 Place of Birth: Illinois Marital Status: Married to Anne M. Yahanda, M.D. Education: 9/73-6/76 Harvard College, Cambridge, Massachusetts, A.B. (Economics) 9/76-6/77 Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, A.M. (Economics) 7/77-10/82 Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Ph.D. (Economics) 8/77-6/83 Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, M.D. Clinical Training: 6/83-6/86 Internship and Residency in Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts Licensure and Certification: 9/86 American Board of Internal Medicine (Certificate Number 107925) 6/86 California Board of Medical Quality Assurance (G057349) Academic Appointments: 6/83-6/86 Clinical Fellow in Medicine, Harvard Medical School 1/86-6/86 Christopher Walker Research Fellow, Center for Health Policy and Management, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University 6/86-8/93 Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine 6/86-8/93 Assistant Professor, by courtesy, Department of Economics, Stanford University 9/88-8/93 Assistant Professor, by courtesy, Department of Health Research and Policy, Stanford University School of Medicine 8/93-8/98 Associate Professor of Medicine (tenured), Division of General Internal Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine 8/93-8/98 Associate Professor, by courtesy, Department of Economics and Department of Health Research and Policy, Stanford University 9/97-8/11 Senior Fellow, Institute for International Studies, Stanford University 9/98-8/11 Henry J. -

Chandra CV May 5, 2021

Amitabh Chandra 79 JFK Street Harvard Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 email: [email protected] Citizenship United States India (overseas citizen) Degrees, Chronological MA Honorary Degree, Harvard University, 2009 Ph.D Economics, University of Kentucky, 2000 Dissertation: Labor Market Dropouts and the Racial Wage Gap, 1940-1990 MS Economics, University of Kentucky, 1999 BA Economics, University of Kentucky, 1996 Employment July 2020 - present John H. Makin Visiting Scholar American Enterprise Institute July 2018 - present: Henry and Allison McCance Family Professor of Business Administration Faculty Chair, MS/MBA Program in the Life-Sciences Harvard Business School July 2015 – present Ethel Zimmerman Wiener Professor of Public Policy Harvard Kennedy School of Government April 2009 – present Professor and Director of Health Policy Research Harvard Kennedy School of Government October 2009 – present Research Associate National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) July 2012 - present Panel of Health Advisors Congressional Budget Office ! May 6, 21, p. 1/14 Previous Positions July 2012 - 2014 Visiting Scholar American Enterprise Institute January 2011 - 2012 Special Commissioner Massachusetts Commission on Provider Price Reform December 2011 - 2019 Chair Editor and Editor Review of Economics and Statistics April 2011 - 2016 Consultant Microsoft Research April 2008 - 2015 Associate Editor American Economic Journal: Applied July 2008 - 2012 Co-Editor Journal of Human Resources July 2005 -

HARVARD LIBRARY Governance

HARVARD LIBRARY Administrative Organization CLAUDINE GAY ALAN GARBER Faculty Advisory As of September 2020 Library Edgerley Family Dean of the Provost Council to the Board Faculty of Arts and Sciences Harvard Library Birkhoff Mathematical Library * Botany Libraries * Cabot Science Library * Faculty of Arts and Gutman Library, HGSE MARTHA Ernst Mayr Library * Sciences Alex Hodges WHITEHEAD Fine Arts Library * Martha Whitehead Vice President for Fung Library the Harvard Library Library and Knowledge Services, HKS Harvard Film Archive * Faculty of Arts Baker Library, HBS and University School Leslie Donnell Harvard-Yenching Library * and Sciences Librarian; Libraries Debra Wallace Houghton Library * Libraries Roy E. Larsen Harvard Law School Library Lamont Library * Librarian Andover-Harvard Jocelyn Kennedy Loeb Music Library * for the Faculty of Theological Library, HDS Physics Research Library * Arts and Sciences Douglas Gragg Countway Library, HMS Robbins Library of Philosophy Elaine Martin Tozzer Library * Frances Loeb Library, GSD Widener Library * Ann Whiteside Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute Wolbach Library Marilyn Dunn * Harvard College Library FRANZISKA FREY THOMAS HYRY ELIZABETH KIRK MEGAN STY SNYDMAN KIM VAN SAVAGE VAUGHN WATERS SUZANNE WONES LAURA WOOD Chief of Staff and Florence Associate SNIFFIN- Managing Director Human Resources Director of Associate Associate Senior Advisor for Fearrington University Librarian MARINOFF Library Technology Director Administration and University Librarian University Librarian University -

Annual Report 2017 2017 HUTCHINS CENTER for AFRICAN & AFRICAN AMERICAN RESEARCH

ANNUAL REPORT Annual Report 2017 2017 HUTCHINS CENTER FOR AFRICAN & AFRICAN AMERICAN RESEARCH Hutchins Center for African & African American Research Harvard University 104 Mount Auburn Street, 3R Cambridge, MA 02138 617.495.8508 Phone 617.495.8511 Fax HARVARD [email protected] HutchinsCenter.fas.harvard.edu Facebook.com/HutchinsCenter UNIVERSITY Twitter.com/HutchinsCenter 17070002_Cvr.indd 1 7/7/17 4:14 PM Annual Report 2017 4 12 Letter from the Director 15 Highlights of the Year 29 Flagships of the Hutchins Center 75 A Synergistic Hub of Intellectual Fellowship 91 Annual Lecture Series 94 Archives, Manuscripts, and Collections 96 Research Projects and Outreach 104 Our Year in Events 110 Staff 112 Come and Visit Us Harvard University 17070002_Guts.indd 2 7/7/17 6:32 PM 29 44 54 58 Project on Race, Class 64 & Cumulative Adversity at the Hutchins Center Harvard University 65 67 70 71 73 74 17070002_Guts.indd 3 7/7/17 6:32 PM Director Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Executive Director Abby Wolf The Hutchins Center for African & African American Research is fortunate to have the support of Harvard University President Drew Gilpin Faust, Provost Alan M. Garber, Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Michael D. Smith, Dean of Social Science Claudine Gay, Administrative Dean for Social Science Beverly Beatty, and Senior Associate Dean for Faculty Development Laura Gordon Fisher. What we are able to accomplish at the Hutchins Center would not be possible without their generosity and engagement. Glenn H. Hutchins, Chair, National Advisory Board. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Abby Wolf. -

David M. Cutler Department of Economics Harvard University 226

David M. Cutler Department of Economics Harvard University 226 Littauer Center - 1805 Cambridge Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Phone: (617) 496-5216 [email protected] Website Employment 2005-: Otto Eckstein Professor of Applied Economics, Department of Economics and Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University 2014-2019: Harvard College Professor, Harvard University 2003-2008: Social Sciences Dean, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University 1997-2005: Professor of Economics, Department of Economics and Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University 1995-1997: John L. Loeb Associate Professor of Social Sciences, Harvard University 1993: On leave as Senior Staff Economist, Council of Economic Advisers and Director, National Economic Council 1991-1995: Assistant Professor of Economics, Harvard University Other Affiliations Academic and Policy Advisory Board, Kyruss, Incorporated National Advisory Board, Firefly Board Member, Center for Healthcare Transparency Consultant, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. Consultant, Mercer Health & Benefits, LLC Fellow, Employee Benefit Research Institute Litigation. Retained by counsel for plaintiffs to provide expert services in pending litigation involving opioid pharmaceuticals. Member, Institute for Research on Poverty Member, Institute of Medicine Member, National Academy of Social Insurance Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research, Aging, Health Care, Public Economics, and Productivity programs Scientific Advisory Board, Alliance for Aging Research Scientific Advisory Board, -

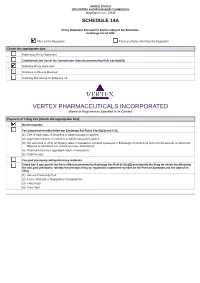

VERTEX PHARMACEUTICALS INCORPORATED (Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 14A Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Filed by the Registrant Filed by a Party other than the Registrant Check the appropriate box: Preliminary Proxy Statement Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) Definitive Proxy Statement Definitive Additional Materials Soliciting Material under §240.14a-12 VERTEX PHARMACEUTICALS INCORPORATED (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): No fee required. Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. (1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: (2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: (3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): (4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: (5) Total fee paid: Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the Form or Schedule and the date of its filing. (1) Amount Previously Paid: (2) Form, Schedule or Registration Statement No.: (3) Filing Party: (4) Date Filed: Dear Shareholders: 2019 was a remarkable year for Vertex as all parts of our business - research, development, commercial and business development - performed at exceptional levels. -

Alan M. Garber, Provost of Harvard University

Harvard School of Public Health | Alan M. Garber, Provost of Harvard University BETTY Good afternoon, and welcome to the Voices in Leadership series. This program focuses on the nexus of science JOHNSON: and leadership to create positive change in the world of public health. I am Betty Johnson, and I have the privilege to direct and introduce this program. Our guest today could be called a Renaissance man of academia. When he was a university freshman, he said, and I quote, "I was a reluctant and ambivalent pre-med student. But after being exposed to an economics course, I switched my major to a concentration from biochemistry to economics," end quote. This switch in plan ultimately led to a PhD in economics from Harvard, while at the same time he was earning an MD degree from Stanford. Today, Dr. Alan Garber's career combines both interests. And it is no surprise that this combination of a love for science and economics eventually landed him a role as university provost. But not as any university provost, our university provost. In a political climate in Washington, DC, where robust research funded is under threat, Dr. Alan Garber is perfectly suited to lead Harvard's efforts to ensure the research pipeline remains strong. His intellectual interests are far reaching. At Stanford, he was a fellow in both the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. He also served as director for Stanford Center for Health Policy and Center for Primary Care and Outcomes Research at Stanford School of Medicine. -

Learning's Leading Edges

JOHN HARVARD'S JOURNAL They point to the checks and balances Learning’s Leading Edges each person’s characteristic style. There used to ensure that research is under- is no evidence, she asserted, supporting taken responsibly, and that each experi- The harvard initiative on Learning the idea that such matching influences ment is evaluated not only on its sci- and Teaching (HILT), unveiled in Octo- learning outcomes. entific merits but also on criteria such ber, was inaugurated in a symposium on Nobel laureate in physics Carl Wie- as whether the research uses the right February 3. More than 300 participants man, a pioneer in effective science educa- species and the fewest possible number convened from all Harvard’s faculties— tion and associate director of science at of animals, and is designed to cause the principally senior professors and deans— the White House Office of Science and least amount of suffering. For certain sci- plus invited panelists with special ex- Technology Policy, noted that although entific questions, such as developing a pertise in the field. HILT is the fruit of a much is known (from cognitive psychol- vaccine to prevent HIV or trying to solve $40-million gift from Gustave M. Hauser, ogy, brain science, and college classroom major problems in neurodegenerative J.D. ’53, and his wife, Rita E. Hauser, L studies) about thinking and learning, disease, other animal models are a poor ’58, who attended the symposium and this knowledge is almost never applied approximation of a human being. Pri- participated actively during the question to teaching techniques. He cited a few re- mates are “only used when lower animals periods (see “Investing in Learning and search results that are well established: won’t work, and they’re used in some Teaching,” January-February, page 60). -

January 16, 2020 Fong Auditorium, Boylston Hall Agenda

FAS Administrators’ Town Hall January 16, 2020 Fong Auditorium, Boylston Hall Agenda Connect with FAS Colleagues Ticknor Lounge Welcome, Introductions, and Updates Leslie Kirwan Harvard Library: from Collections to Martha Whitehead Connections Financial Updates Leslie Kirwan, Jay Herlihy HUIT Charles Kling, Maria Apse, Alan Wolf, Kyle Shachmut Administrative Systems Palooza Mary Ann Bradley Closing / Q & A Session Leslie Kirwan Page 2 Welcome, Introductions, and Updates Leslie Kirwan Dean for Administration and Finance Harvard Library: from Collections to Connections Martha Whitehead Vice President, Roy E. Larsen Librarian for the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Harvard Library and Open Knowledge: Collections and Connections Martha Whitehead, Vice President for the Harvard Library and Roy E. Larsen Librarian for the Faculty of Arts and Sciences FAS Administrators’ Town Hall, January 16, 2020 Outline 1. Research libraries in a global knowledge commons 2. Harvard Library a) Overview b) Sample services c) Key current priorities 3. Discussion Research libraries in a global knowledge commons Our Shared Goal: Collaboratively develop a global knowledge commons for the benefit of our user communities Data at the core, surrounded by enabling layers of: • policy • distributed infrastructure • services that facilitate user engagement with data Data at the Core: Developing a Holistic Vision We have distinct associations, initiatives and parts of our organizations focused on these four different forms of data, but they have similar concerns: • Acquisition -

Overseers' Committee to Visit the Harvard Library

Meeting of the OVERSEERS’ COMMITTEE TO VISIT THE HARVARD LIBRARY March 21–22, 2017 MEETING OF THE OVERSEERS’ COMMITTEE TO VISIT THE HARVARD LIBRARY March 21-22, 2017 Table of Contents I. *Introduction a. Overseers’ Committee to Visit the Harvard Library, Members, 2016-2018 b. Overseers’ Committee to Visit the Harvard Library, Member Bios c. Meeting Agenda d. Presenter Bios e. Campus Map II. *Harvard University: Strategic Directions and Priorities a. Mission and Goals III. Harvard Library Overview a. *Harvard Library Visiting Committee Report, 2014 b. *Harvard Library Management Response, 2015 c. *Memorandum to the Visiting Committee d. *Closing the Book on the Transition: The Harvard Library e. *Budget Overview f. *Harvard Library Allocation Model g. *Objectives in Action 2016-2021 h. *Harvard Library Administrative Organization i. *Harvard Library Committee Structure j. Standing Committee Annual Report k. Report of the Harvard Library Committee System Assessment Working Group IV. Harvard Library’s Digital Strategy a. *Harvard Library Digital Strategy 1.0 b. Research Data Management at Harvard Library c. *Embracing the Library’s Digital Future d. Harvard Law School Library Innovation Lab e. Baker 3.0 f. Charlie Archive at the Harvard Library g. Colonial North America at Harvard Library h. Uncovering Harvard Library’s Hidden Collections i. Web Archiving j. Email Archiving k. The Dataverse Project l. *Strategic Conversations m. *Research, Teaching, and Learning (RTL) Event Flyers V. Lunch with the Library Board and Faculty Advisory Council (FAC) a. FAC Meeting Minutes b. *FAC, Academic Year 2016 c. *Library Board, Academic Year 2016 VI. Collective Collections a. *Summary of Harvard’s Relations and Aspirations b. -

Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc / Ma

VERTEX PHARMACEUTICALS INC / MA FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 02/15/18 for the Period Ending 12/31/17 Address 50 NORTHERN AVENUE BOSTON, MA, 02210 Telephone 6173416393 CIK 0000875320 Symbol VRTX SIC Code 2834 - Pharmaceutical Preparations Industry Biotechnology & Medical Research Sector Healthcare Fiscal Year 12/31 http://www.edgar-online.com © Copyright 2018, EDGAR Online, a division of Donnelley Financial Solutions. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and use of this document restricted under EDGAR Online, a division of Donnelley Financial Solutions, Terms of Use. UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 ________________________________________________________ FORM 10-K x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2017 or o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 000-19319 ____________________________________________ Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Massachusetts 04-3039129 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 50 Northern Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02210 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code (617) 341-6100 ____________________________________________ Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Exchange Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, $0.01 Par Value Per Share The NASDAQ Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Exchange Act: None ______________________________________________ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

A Home for Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Harvard

A Home for Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Harvard Welcome. The Harvard Innovation Labs are a vibrant, cross-disciplinary ecosystem for the Harvard community to explore innovation and entrepreneurship while building deeper connections. The Labs are an excellent example of the One Harvard vision and a leading catalyst for the Allston Science and Enterprise District. The Harvard Innovation Labs began in 2011 with the opening of the i-lab, expanded in 2014 when the Launch Lab opened its doors, and will continue to grow in both breadth and depth with future resources, including a Wet Lab which comes online in 2016 (projected). The Harvard i-lab The i-lab is the central component of the Harvard Innovation Labs ecosystem. It is an educational collaborative for all current Harvard students from any Harvard school to explore innovation and entrepreneurship at any stage. It provides open co- working space, a vibrant community of peer and mentor support, experiential programming, and a 12-week Venture Incubation Program helping student teams take their ideas as far as they can go. The Harvard Launch Lab The Launch Lab is a critical extension of the growing Harvard Innovation Labs ecosystem. It provides eligible Harvard alumni leading high-potential early- stage startups with a curated community including collaborative co-working space, business building programming, and access to i-lab advisors and mentors. It fosters continued connection between alumni, current students and the Harvard community as a whole. Moving Further, Faster There has never been a better time to be a part of innovation at Harvard. The Harvard Innovation Labs have an unprecedented opportunity to continue to shape cross-disciplinary collaboration at Harvard and serve as a catalyst to solving society’s most pressing needs through innovation and entrepreneurship.