A New Description of Cellular Quiescence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

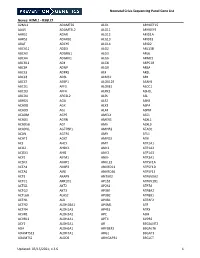

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

4 Understanding the Role of GNA13 Deregulation in Lymphomagenesis

Integrative Genomics Reveals a Role for GNA13 in Lymphomagenesis by Adrienne Greenough University Program in Genetics and Genomics Duke University Approved: ___________________________ Sandeep Dave, Supervisor ___________________________ Fred Dietrich ___________________________ Jack Keene ___________________________ Yuan Zhuang Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Genetics and Genomics in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT Integrative Genomics Reveals a Role for GNA13 in Lymphomagenesis by Adrienne Greenough University Program in Genetics and Genomics Duke University Approved: ___________________________ Sandeep Dave, Supervisor ___________________________ Fred Dietrich ___________________________ Jack Keene ___________________________ Yuan Zhuang An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Genetics and Genomics in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Adrienne Greenough 2014 Abstract Lymphomas comprise a diverse group of malignancies derived from immune cells. High throughput sequencing has recently emerged as a powerful and versatile method for analysis of the cancer genome and transcriptome. As these data continue to emerge, the crucial work lies in sorting through the wealth of information to hone in on the critical aspects that will give us a better understanding of biology and new insight for how to treat disease. Finding the important signals within these large data sets is one of the major challenges of next generation sequencing. In this dissertation, I have developed several complementary strategies to describe the genetic underpinnings of lymphomas. I begin with developing a better method for RNA sequencing that enables strand-specific total RNA sequencing and alternative splicing profiling in the same analysis. -

Multi-Functionality of Proteins Involved in GPCR and G Protein Signaling: Making Sense of Structure–Function Continuum with In

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2019) 76:4461–4492 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03276-1 Cellular andMolecular Life Sciences REVIEW Multi‑functionality of proteins involved in GPCR and G protein signaling: making sense of structure–function continuum with intrinsic disorder‑based proteoforms Alexander V. Fonin1 · April L. Darling2 · Irina M. Kuznetsova1 · Konstantin K. Turoverov1,3 · Vladimir N. Uversky2,4 Received: 5 August 2019 / Revised: 5 August 2019 / Accepted: 12 August 2019 / Published online: 19 August 2019 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract GPCR–G protein signaling system recognizes a multitude of extracellular ligands and triggers a variety of intracellular signal- ing cascades in response. In humans, this system includes more than 800 various GPCRs and a large set of heterotrimeric G proteins. Complexity of this system goes far beyond a multitude of pair-wise ligand–GPCR and GPCR–G protein interactions. In fact, one GPCR can recognize more than one extracellular signal and interact with more than one G protein. Furthermore, one ligand can activate more than one GPCR, and multiple GPCRs can couple to the same G protein. This defnes an intricate multifunctionality of this important signaling system. Here, we show that the multifunctionality of GPCR–G protein system represents an illustrative example of the protein structure–function continuum, where structures of the involved proteins represent a complex mosaic of diferently folded regions (foldons, non-foldons, unfoldons, semi-foldons, and inducible foldons). The functionality of resulting highly dynamic conformational ensembles is fne-tuned by various post-translational modifcations and alternative splicing, and such ensembles can undergo dramatic changes at interaction with their specifc partners. -

Gαo (GNAO1) Encephalopathies: Plasma Membrane Vs. Golgi Functions

www.oncotarget.com Oncotarget, 2018, Vol. 9, (No. 35), pp: 23846-23847 Editorial Gαo (GNAO1) encephalopathies: plasma membrane vs. Golgi functions Gonzalo P. Solis and Vladimir L. Katanaev Heterotrimeric G proteins are key signaling of Ca2+ currents by norepinephrine [5]. Intriguingly, molecules best recognized as the immediate transducers mutations in other five residues did not compromise (or of GPCRs (G protein coupled receptors). A heterotrimeric only slightly affected) α2A adrenergic receptor signaling G protein complex consists of three subunits, α, β, [4]. Thus, it is highly plausible that Gαo functions beyond and γ, of which the Gα is responsible for binding to its canonical role as GPCR-transducer also contribute to guanine nucleotides and to the cognate GPCR. Ligand- the development of Gαo encephalopathies. activated GPCRs catalyze the GDP-GTP exchange on The functional localization of heterotrimeric G Gα inducing the dissociation of Gα-GTP from Gβγ, both proteins at the plasma membrane (PM) is widely accepted. being competent to engage downstream effectors. GTP However, an increasing amount of data indicate that they hydrolysis returns the Gα to its GDP-bound state allowing also work at different cellular compartments, especially the formation of the heterotrimeric G protein, which binds at the Golgi apparatus [6]. Recently, we identified >250 the cognate GPCR for a subsequent activation cycle. proteins as potential Gαo interacting partners, and During the last five years, whole-exome sequencing subsequently uncovered a non-canonical Gαo signaling of patients with severe infantile encephalopathies resulted involved in the regulation of vesicular trafficking at the in an avalanche of de novo heterozygous mutations Golgi [7]. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material. S1. Images from automatic imaging reader Cytation™ 1. A, A’, A’’ present the same field of view. Cells migrating from the upper compartment of the inserts are stained with DID (red color), Cell nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue color). A’ and A’’ demonstrate the method of analysis (A’ – nuclei numbering, A’’ – migrating cells numbering), scale bar – 300 µm. ASC BM-MSC Y BM-MSC A mean SEM mean SEM mean SEM CXCL6 2.240 0.727 4.158 0.677 2.149 1.816 CXCL16 4.277 0.248 0.763 0.405 1.130 0.346 CXCL12 -2.855 0.483 -4.528 0.226 -3.616 0.318 SMAD3 -0.511 0.191 -1.522 0.188 -1.332 0.215 TGFB2 3.742 0.533 1.238 0.210 0.990 0.568 COL14A 1.532 0.357 -0.397 0.736 -1.522 0.469 MHX 1.397 0.414 1.145 0.412 0.642 0.613 SCX 2.984 0.301 2.062 0.320 2.031 0.249 RUNX2 3.290 0.359 2.319 0.388 2.546 0.529 PPRAG 1.720 0.303 2.926 0.423 2.912 0.215 Supplementary material S3. The table provides the mean Δct and SEM values for all genes and all groups analyzed in this study (n=8 in each group). Supplementary material S2. The table provides the list of genes which displayed significantly different expression between hASCs and hBM-MSCs A based on microarray nr Exp p-value Exp Fold Change ID Symbol Entrez Gene Name 1 2.84E-05 16.896 16960355 TM4SF1 transmembrane 4 L six family member 1 2 9.10E-09 12.238 16684080 IFI6 interferon alpha inducible protein 6 3 3.93E-08 11.851 16667702 VCAM1 vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 4 1.54E-05 9.944 16840113 CXCL16 C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 16 5 2.01E-06 9.123 16852463 RAB27B RAB27B, member RAS oncogene -

Identification of Transcriptional Mechanisms Downstream of Nf1 Gene Defeciency in Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors Daochun Sun Wayne State University

Wayne State University DigitalCommons@WayneState Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 Identification of transcriptional mechanisms downstream of nf1 gene defeciency in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors Daochun Sun Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Sun, Daochun, "Identification of transcriptional mechanisms downstream of nf1 gene defeciency in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 558. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. IDENTIFICATION OF TRANSCRIPTIONAL MECHANISMS DOWNSTREAM OF NF1 GENE DEFECIENCY IN MALIGNANT PERIPHERAL NERVE SHEATH TUMORS by DAOCHUN SUN DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2012 MAJOR: MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND GENETICS Approved by: _______________________________________ Advisor Date _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY DAOCHUN SUN 2012 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my parents and my wife Ze Zheng for their continuous support and understanding during the years of my education. I could not achieve my goal without them. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express tremendous appreciation to my mentor, Dr. Michael Tainsky. His guidance and encouragement throughout this project made this dissertation come true. I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Raymond Mattingly and Dr. John Reiners Jr. for their sustained attention to this project during the monthly NF1 group meetings and committee meetings, Dr. -

Methylation of Leukocyte DNA and Ovarian Cancer

Fridley et al. BMC Medical Genomics 2014, 7:21 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1755-8794/7/21 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Methylation of leukocyte DNA and ovarian cancer: relationships with disease status and outcome Brooke L Fridley1*, Sebastian M Armasu2, Mine S Cicek2, Melissa C Larson2, Chen Wang2, Stacey J Winham2, Kimberly R Kalli3, Devin C Koestler1,4, David N Rider2, Viji Shridhar5, Janet E Olson2, Julie M Cunningham5 and Ellen L Goode2 Abstract Background: Genome-wide interrogation of DNA methylation (DNAm) in blood-derived leukocytes has become feasible with the advent of CpG genotyping arrays. In epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), one report found substantial DNAm differences between cases and controls; however, many of these disease-associated CpGs were attributed to differences in white blood cell type distributions. Methods: We examined blood-based DNAm in 336 EOC cases and 398 controls; we included only high-quality CpG loci that did not show evidence of association with white blood cell type distributions to evaluate association with case status and overall survival. Results: Of 13,816 CpGs, no significant associations were observed with survival, although eight CpGs associated with survival at p < 10−3, including methylation within a CpG island located in the promoter region of GABRE (p = 5.38 x 10−5, HR = 0.95). In contrast, 53 CpG methylation sites were significantly associated with EOC risk (p <5 x10−6). The top association was observed for the methylation probe cg04834572 located approximately 315 kb upstream of DUSP13 (p = 1.6 x10−14). Other disease-associated CpGs included those near or within HHIP (cg14580567; p =5.6x10−11), HDAC3 (cg10414058; p = 6.3x10−12), and SCR (cg05498681; p = 4.8x10−7). -

Qt38n028mr Nosplash A3e1d84

! ""! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I dedicate this thesis to my parents who inspired me to become a scientist through invigorating scientific discussions at the dinner table even when I was too young to understand what the hippocampus was. They also prepared me for the ups and downs of science and supported me through all of these experiences. I would like to thank my advisor Dr. Elizabeth Blackburn and my thesis committee members Dr. Eric Verdin, and Dr. Emmanuelle Passegue. Liz created a nurturing and supportive environment for me to explore my own ideas, while at the same time teaching me how to love science, test my questions, and of course provide endless ways to think about telomeres and telomerase. Eric and Emmanuelle both gave specific critical advice about the proper experiments for T cells and both volunteered their lab members for further critical advice. I always felt inspired with a sense of direction after thesis committee meetings. The Blackburn lab is full of smart and dedicated scientists whom I am thankful for their support. Specifically Dr. Shang Li and Dr. Brad Stohr for their stimulating scientific debates and “arguments.” Dr. Jue Lin, Dana Smith, Kyle Lapham, Dr. Tet Matsuguchi, and Kyle Jay for their friendships and discussions about what my data could possibly mean. Dr. Eva Samal for teaching me molecular biology techniques and putting up with my late night lab exercises. Beth Cimini for her expertise with microscopy, FACs, singing, and most of all for being a caring and supportive friend. Finally, I would like to thank Dr. Imke Listerman, my scientific partner for most of the breast cancer experiments. -

Diallyl Disulfide Inhibits the Proliferation of HT-29 Human Colon Cancer Cells by Inducing Differentially Expressed Genes

MOLECULAR MEDICINE REPORTS 4: 553-559, 2011 Diallyl disulfide inhibits the proliferation of HT-29 human colon cancer cells by inducing differentially expressed genes YOU-SHENG HUANG1,2, NA XIE1,2, QI SU1, JIAN SU1, CHEN HUANG1 and QIAN-JIN LIAO1 1Cancer Research Institute, University of South China, Hengyang, Hunan 421001; 2Department of Pathology, Hainan Medical University, Haikou, Hainan 571101, P.R. China Received November 22, 2010; Accepted February 28, 2011 DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2011.453 Abstract. Diallyl disulfide (DADS), a sulfur compound Introduction derived from garlic, has been shown to have protective effects against colon carcinogenesis in several studies performed in Colon cancer is one of the major causes of cancer death rodent models. However, its molecular mechanism of action worldwide (1). An understanding of the mechanisms involved remains unclear. This study was designed to confirm the anti- in the occurrence and development of colon cancer would aid proliferative activity of DADS and to screen for differentially in its therapy. Epidemiological investigations have provided expressed genes induced by DADS in human colon cancer cells compelling evidence that environmental factors are modifiers with the aim of exploring its possible anticancer mechanisms. in colon cancer (1-3); diet has also been shown to be an impor- The anti-proliferative capability of DADS in the HT-29 human tant determinant of cancer risk and tumor behavior (3-5). colon cancer cells was analyzed by MTT assays and flow Garlic consumption is very popular all over the world. cytometry. The differences in gene expression between DADS- Epidemiological studies have shown an inverse correlation treated (experimental group) and untreated (control group) between the consumption of garlic and colon cancer in certain HT-29 cells were identified using two-directional suppression areas (6). -

Solute Carrier Transporters (Slcs) As Possible Drug Targets for Cystic Fibrosis

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS DEPARTAMENTO DE QUÍMICA E BIOQUÍMICA Solute Carrier Transporters (SLCs) as Possible Drug Targets for Cystic Fibrosis Íris Lameiro Petinga Mestrado em Bioquímica Especialização em Bioquímica Médica Dissertação orientada por: Professora Doutora Margarida D. Amaral 2017 Acknowledgments/Agradecimentos Ao concluir este trabalho não posso deixar de agradecer a todas as pessoas que contribuíram de alguma maneira para a sua realização. Em primeiro lugar gostaria de agradecer à professora Margarida Amaral não só por me ter recebido no seu laboratório e grupo de investigação, mas também por toda a orientação e acompanhamento e acima de tudo confiança depositada. Não podia deixar também de agradecer ao professor Carlos Farinha por se ter mostrado sempre disponível para me ajudar, por toda a atenção, paciência e por me ter cativado para a área do estudo da Fibrose Quística desde muito cedo. Agradeço a todos os meus colegas de laboratório que sempre se mostraram disponíveis para me ajudar, todos eles à sua maneira. Primeiramente gostaria de agradecer à Verónica que tornou todos os infindáveis “Colony PCR” mais divertidos e me ajudou a seguir em frente quando tudo corria mal. À Sara cuja paciente infinitiva em me ensinar a trabalhar na cultura e grande parte das outras técnicas que utilizei neste trabalho, para além de responder sempre com boa disposição a todas as minhas dúvidas e questões que foram enumeras e muitas delas sem nexo, por vezes. À Madalena e aos seus maravilhosos cadernos de laboratório, sem dúvida a minha fonte de inspiração, mesmo longe esteve sempre disponível para responder às minhas dúvidas por mais chatas e aborrecidas que fossem e me fez crer desde o primeiro dia que seria possível. -

Supplemental Table 1 List of Genes Differentially Expressed In

Supplemental Table 1 List of genes differentially expressed in normal nasopharyngeal epithelium (N), metaplastic and displastic lesions (R), and carcinoma (T). Parametric Permutation Geom Geom Geom Unique Description Clone UG Gene symbol Map p-value p-value mean mean mean id cluster of of of ratios ratios ratios in in in class class class 1 : N 2 : R 3 : T 1 p < 1e-07 0 0.061 0.123 2.708 169329 secretory leukocyte protease IncytePD:2510171 Hs.251754 SLPI 20q12 inhibitor (antileukoproteinase) 2 p < 1e-07 0 0.125 0.394 1.863 163628 sodium channel, nonvoltage-gated IncytePD:1453049 Hs.446415 SCNN1A 12p13 1 alpha 3 p < 1e-07 0 0.122 0.046 1.497 160401 carcinoembryonic antigen-related IncytePD:2060355 Hs.73848 CEACAM6 19q13.2 cell adhesion molecule 6 (non- specific cross reacting antigen) 4 p < 1e-07 0 0.675 1.64 5.594 165101 monoglyceride lipase IncytePD:2174920 Hs.6721 MGLL 3q21.3 5 p < 1e-07 0 0.182 0.487 0.998 166827 nei endonuclease VIII-like 1 (E. IncytePD:1926409 Hs.28355 NEIL1 15q22.33 coli) 6 p < 1e-07 0 0.194 0.339 0.915 162931 hypothetical protein FLJ22418 IncytePD:2816379 Hs.36563 FLJ22418 1p11.1 7 p < 1e-07 0 1.313 0.645 13.593 162399 S100 calcium binding protein P IncytePD:2060823 Hs.2962 S100P 4p16 8 p < 1e-07 0 0.157 1.445 2.563 169315 selenium binding protein 1 IncytePD:2591494 Hs.334841 SELENBP1 1q21-q22 9 p < 1e-07 0 0.046 0.738 1.213 160115 prominin-like 1 (mouse) IncytePD:2070568 Hs.112360 PROML1 4p15.33 10 p < 1e-07 0 0.787 2.264 3.013 167294 HRAS-like suppressor 3 IncytePD:1969263 Hs.37189 HRASLS3 11q12.3 11 p < 1e-07 0 0.292 0.539 1.493 168221 Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ13510 IncytePD:64451 Hs.37896 2 fis, clone PLACE1005146. -

4211C3bea57068cc0a32976fb2

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Multiple Known Mechanisms and a Possible Role of an Enhanced Immune System in Bt-Resistance in a Field Population of the Bollworm, Helicoverpa zea: Differences in Gene Expression with RNAseq Roger D. Lawrie 1,2 , Robert D. Mitchell III 3, Jean Marcel Deguenon 2, Loganathan Ponnusamy 2 , Dominic Reisig 4, Alejandro Del Pozo-Valdivia 4, Ryan W. Kurtz 5 and R. Michael Roe 1,2,* 1 Department of Biology/Environmental and Molecular Toxicology Program, 850 Main Campus Dr, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Campus Box 7647, 3230 Ligon Street, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA; [email protected] (J.M.D.); [email protected] (L.P.) 3 Knipling-Bushland US Livestock Insects Research Laboratory Genomics Center, 2700 Fredericksburg Road, United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, Kerrville, TX 78028, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Vernon G. James Research & Extension Center, 207 Research Station Road, Plymouth, NC 27962, USA; [email protected] (D.R.); [email protected] (A.D.P.-V.) 5 Cotton Incorporated, 6399 Weston Parkway, Cary, NC 27513, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-919-515-4325 Received: 31 July 2020; Accepted: 1 September 2020; Published: 7 September 2020 Abstract: Several different agricultural insect pests have developed field resistance to Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) proteins (ex. Cry1Ac, Cry1F, etc.) expressed in crops, including corn and cotton. In the bollworm, Helicoverpa zea, resistance levels are increasing; recent reports in 2019 show up to 1000-fold levels of resistance to Cry1Ac, a major insecticidal protein in Bt-crops.